Becoming Elizabeth Arden

A Conversation about the Beauty Tycoon with Historian Stacy A. Cordery

“Arden knew that beauty equaled strength, and that a woman who felt beautiful could conquer the world. The creation of beauty drove her. Beauty was behind every business decision she made, and it brought her wealth, acceptance, and international fame.” – Stacy A. Cordery

After researching and writing about Elizabeth Arden’s Maine Chance spas (both the original and Arizona locations), I was intrigued and wanted to learn more about this groundbreaking female businesswoman—a completely self-created woman (down to her name) who went from Ontario farm girl to international beauty mogul. Historian Stacy A. Cordery’s new book, Becoming Elizabeth Arden: The Woman Behind the Global Beauty Empire, answered all my questions and more, delving into every aspect of the life and career of the woman who made makeup respectable and who created the idea of a holistic approach to beauty.

A professor of History at Iowa State University in Ames, Cordery is the author of Alice: Alice Roosevelt Longworth, from White House Princess to Washington Power Broker, Juliette Gordon Low: The Remarkable Founder of the Girl Scouts, and two books about Theodore Roosevelt. As Cordery explains on her website, she finds “people endlessly fascinating—their choices, their justifications, their joys and sorrows, their innate nobility. When one interesting individual intersects with larger social forces then historical biography is born.” Arden was definitely an interesting individual whose life intersected with many of the major social and cultural movements and moments of the first half of the twentieth century—her business’ rise in tandem with women’s increasing visibility in America. Cordery deftly weaves together suffrage, two world wars, and globalization with Arden’s pioneering beliefs about skin care, exercise, cosmetics, health, and femininity, as well as her pioneering (and very successful) foray into thoroughbred racing (she won the Kentucky Derby in 1947). Well-researched and eminently readable, Becoming Elizabeth Arden should be first on your list if you want to learn more about this petite powerhouse—a woman Cordery describes as “self-taught in the masculine world of business…” whose “feminine appearance, little-girl voice, and demure public demeanor cloaked a driving ambition.”

I spoke with Stacy last week about the research and writing process for Becoming Elizabeth Arden, her background as a historian, what led her to Arden, and much more. Becoming Elizabeth Arden is now available on Bookshop, Amazon, and wherever books are sold.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Laura: I thought it was interesting that your other books seem to primarily focus on political figures, like Theodore Roosevelt and Alice Roosevelt Longworth. What led you to want to write about Elizabeth Arden as a beauty tycoon and innovator?

Stacy: I am a Roosevelt scholar, it's true, and I got to T.R. through Alice, really. I started in large measure because of the interest of my graduate school advisor. My dissertation was on Alice, and I veered off into T.R. because I felt like I knew a lot about Alice but didn't know too much about her father. Since he was the primary figure in her life, because the dissertation was really about Alice until she married, I thought I better learn something more about T.R. Since then, and since the Alice book came out, I really think of myself as a biographer of women. What Arden is, is the third biography [along with Longworth and Juliette Gordon Low] of a really impressive woman of high achievement who's been ignored by historians, and that's really the lines she fits in for me.

The question about how I got there, there's a twofold answer, and that is that I'm a Viking author. Penguin has the right of first refusal about what I write about. As a historian, she has to be dead, I have got to have some sources, and she has to have, for Viking, enough name recognition that people will buy the book, but she can't have been written about in the immediate past because then the book won't sell. Anyway, so there's all those sorts of things where my editor and agent are concerned. Then I probably sent 20 different ideas to my editor, and she shot them all down, so we landed on Arden.

My personal connection to Arden is that when I was a young teenager, my mother, who was a very tactful woman, said, "Stacy, I've signed us up for mother-daughter day at the Elizabeth Arden salon." I'm like, "Cool. Okay." Mom thought it was time I learned about skincare, and as she told me, "No one knows more about skincare than Elizabeth Arden. We're going to go to the experts. This is a lifelong thing. We're going to learn about it," so we did. We had a wonderful time. Lots of mothers, lots of daughters. We took home some bling. It was great.

The other thing we learned about, of course, was the other thing for which Elizabeth Arden was so famous, and that is makeup. In those early days—it was, like I said, the early '70s—I was deeply wedded to my own look, which was based on tons of light blue eyeshadow and green mascara at the same time. I think my mom was like, "Maybe Arden can teach her more about the Arden look; a little more sophistication, a little less color."

I still have that jar of Eight Hour Cream that my mom and I bought when we were there. The label has worn off it, but honestly, that's my Madeline. When I open it, it brings my mom back. She's been gone for over two decades now. That's a strange thing. Because if you've ever smelled Eight Hour Cream, you know it's not everybody's favorite scent, but it does remind me of my mom. In that long path to try to discover the next person I could write about that would make me happy and be interesting to a reading audience but would also make my editor and my publisher happy, that's how we got to Elizabeth Arden.

Laura: I love that there's a personal connection beyond just the historical connection. What drew you to history in the first place? What's your background?

Stacy: My background is that I have an undergraduate degree in theater. I've been acting since I was old enough to walk across the stage. I took a class as an undergraduate with an extraordinary theater historian by the name of Oscar Brockett. He made me aware of the fact that while I might have a deep appreciation for the written word that is the play and for the storytelling that we do as human animals on the stage, I really had no idea when I played Kate in “Kiss Me, Kate,” I had no idea what was going on in the world around then. I couldn't tell you who was in the presidency or what kinds of movements were underway. At some point in time in Dr. Brockett's class, I think I went, "Oh, there's a whole context that I'm missing here." Dr. Brockett and then another historian at the University of Texas where I did my degrees, I think really moved me away from theater and into history.

I was really captured the moment I held a letter in my handwritten by Eleanor Roosevelt, who was my hero, so many women's heroes, so many people's hero, and I thought, "Okay, this is real in a way it hadn't been before." That primary source—I think that was the beginning of it, and that was the beginning of the door into the Roosevelts as well.

Laura: Wonderful. Yes, talking about primary sources; as you mentioned in the book, Elizabeth Arden didn't leave an archive. How did you approach doing a biography of someone who didn't leave any papers behind?

Stacy: Well, maybe she did and maybe she didn't. Lindy Woodhead [who wrote the book War Paint: Madame Helena Rubinstein and Miss Elizabeth Arden: Their Lives, Their Times, Their Rivalry] claims that there's an Elizabeth Arden archive out there somewhere. I couldn't find it. I asked archivists… Nobody could find it anywhere. I tried in England. I tried in the United States. Nobody. Lindy Woodhead was an industry insider in England. I think it's quite possible that what she called Elizabeth Arden archives was probably some sort of file drawer or file cabinet whenever she worked there. She also said Arden kept diaries, but I don't believe Arden graduated from high school, and I don't think that Arden compulsively kept a personal diary and a business diary like Woodhead wrote that she did.

As I said to my editor at the time this project started, Arden is so famous that there are so many public sources that I could certainly write a biography based on public sources. It wouldn't be my preference, of course, but I've also been researching for many decades and I'm not that bad at it. There were letters and some other sorts of documents in strange places. She had a friendship with Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O'Keeffe, so there were letters there at Yale. There were letters that had to do with her business at the American Medical Association Archives in Chicago about the purity of her products and so forth.

Little by little, I tracked down some of her friends, [gossip columnist] Hedda Hopper and some others, and found six letters here, three letters there, 25 letters here. That, with the larger context that I know, and then the industry periodicals and advertisements, and just the fact that she was so famous that she was covered both in business and in cosmetics industry or fashion industry journals, I hope I compiled enough of a primary source foundation that I turned out an interesting story for readers.

Laura: Yes, you definitely did. I've always thought she was fascinating but have never delved that deeply into her personal life. I really feel like I learned a lot about her and how she operated as a businesswoman and as a tycoon and racehorse owner. What were some of the most interesting things that you felt when you were uncovering in your research?

Stacy: I didn't know anything really about her service during World War II. To me, that was amazing. All of it was amazing. Her fascination with the Marines and other women in uniform was pretty incredible. She loved hanging out with those women in uniform. You could really tell from the things that she wrote that were she just a little bit younger, she really would have… she wanted to be there. I think she was really chuffed to have an insider's view in the way she did.

I love that she worked with Kappa Kappa Gamma for these women's service centers. I thought that was phenomenal. I didn't know these women's service centers existed before, and so to learn about this, it's cool, isn't it? It's all these women. Arden lived and worked in a world of women. To tap into the women's fraternity movement through Kappa Kappa Gamma, to serve women in uniform, I just think that's wonderful in a way that it's hard to cover.

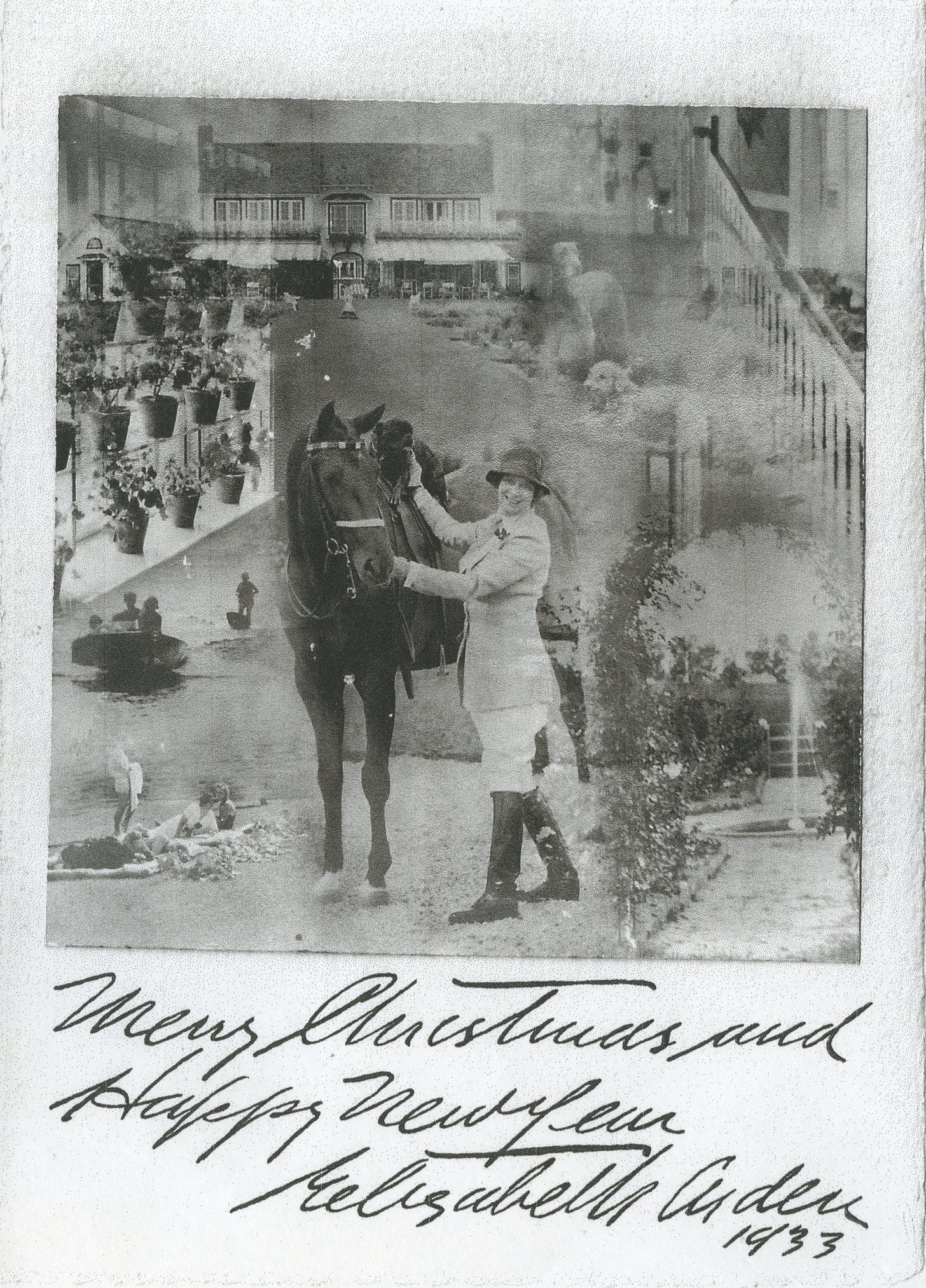

I thought the fires in the barns were—seriously, I cried when I read about how many of her horses died, and I know how much they meant to her. She carried pictures of them in her wallet, and her Christmas cards sometimes had photos of her horses on them. Other friends of hers attested to her deep concern for these horses, and simply the fact that she showed up trackside all the time. She was not a hands-off owner. When she lost those horses in not one fire, but two, that was terrible. Then to think that there might be some kind of a conspiracy out to get her as a thoroughbred horse owner, whether that was about class or gender, I don't know, and I couldn't prove it, but there were sure hints of it in there. That was really interesting to think about.

I assumed because she was a phenomenally successful entrepreneur that she had those qualities that entrepreneurs have: She was driven. She was passionate. She had an unflagging belief in her own ability to help women. These things I expected. What I didn't expect was to see, was that she was one of the first, if not the first, beauty experts dedicated to a holistic understanding of beauty. Diet, exercise, the health of the skin, the importance of relaxation, all this. Then makeup. Makeup was the last thing. Fashion, posture, all this stuff comes together in one big, important, whole system of beauty for Arden, but it wasn't just about makeup.

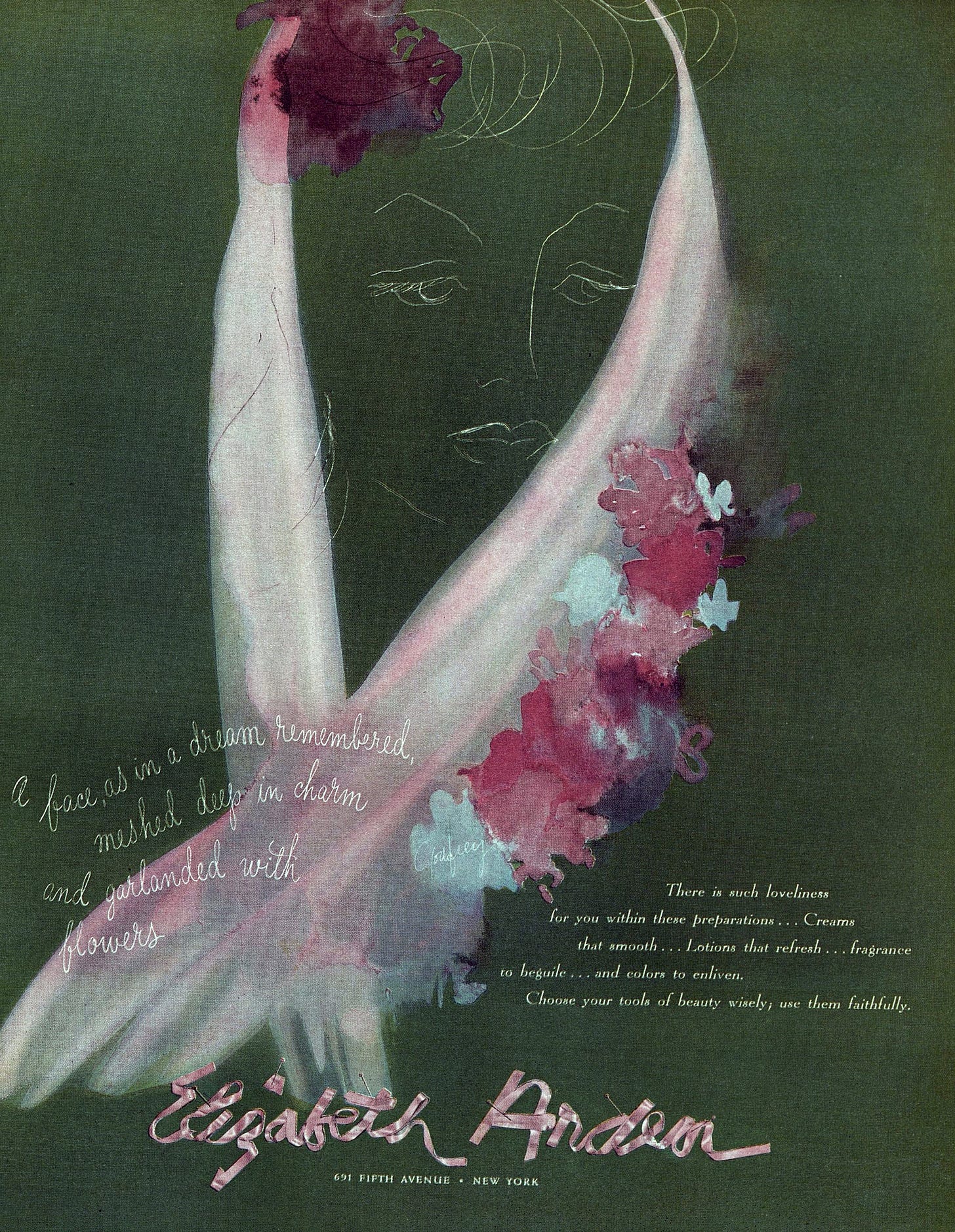

Despite my introduction to Arden as a young teenager, when I think about Arden, I mostly think about makeup. For me to understand her true commitment to this belief of beauty is power, and for a woman, the power that beauty brings is the power to do and achieve anything she wants to. For Arden, it was never, “beauty is what will enable you to snag a man.” I read decades' worth of her advertisements, and they're not about men. They're not. They're about a woman achieving. Whether that's being a great mother, or being a great CEO, or being a terrific WAC [Women’s Army Corps], it was all of a piece to her. The posture, and the clothing, and the skin, and the exercise, and the diet, all this stuff together, which she uniquely believes she could give to you, this holistic system is very modern to me, and so I didn't expect that either.

Laura: Going back to the World War II, I was really surprised that she was an FBI informant. I had no idea about that. How did you discover that?

Stacy: It was really hard to track down, and that's online. I found that in the early days of COVID, when the archives were closed, I couldn't go anywhere, so I did an awful deep dive into what I could find on the internet. When she turned up there, I was shocked, but then I wasn't, because when you think about her salons, everywhere, from Rio de Janeiro to London, you think, oh, the women who would be able to afford the time and the money to go to a salon during the war, you would imagine they would have things to gossip about or things to say in the salon.

It does seem that given what I already knew of her patriotism, because she was motivated by patriotism as a transatlantic business owner, it would make sense to me that she would say to her employees, probably, "Let me know what you hear and I'm interested in it." Yes, that was fun. There's not a lot of information about it. I have no idea how effective she was or how useful she was to Hoover, but Hoover pops up again later in her divorce, so I know they knew one another and that was a big surprise. Her FBI file is accessible easily. You just have to Google it. The rest of it, finding out her as an informant, that takes a deeper dive.

Laura: There have been books and documentaries and musicals about Arden and Helena Rubinstein’s supposed rivalry, but in your book you say that there wasn't one. How did you come to get that conclusion, and why do you think that that rivalry has so much power in the media?

Stacy: Well, it has power in the media because it's a good story. Anytime you can get a good catfight together, oh, well, people will eat that up. It's not that they were competitors, or that Rubinstein wasn't a competitor. She absolutely was. My point is she was never the only competitor, and at times, she wasn't a competitor at all. For that short amount of time that she sold her company, she, the woman, wasn't a competitor at all.

I think that both Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden referred to their competitors as “that man” and “that woman” and simply refused to say their names. I think that was just in the ethos of the era… While Elizabeth Arden certainly kept her eye on Helena Rubinstein, and they certainly had crossover customers, I don't think you could find a whole bunch of women who were only Elizabeth Arden or only Helena Rubinstein [customers]. I'm sure they existed. People are loyal.

My point is what got played up in the past is the idea that they never met, which was absolutely wrong. Of course, they met. I can prove it. I think that they liked to play that up because it got them publicity, and both women were acutely aware of the power of publicity. Helena Rubinstein was the one who said over and over again, "We never met." Arden didn't say that.

I think it's just a good story. A competitor, certainly, but not the only competitor, and at many times, not even the most important competitor. Charles Revson for a while was the most important competitor. At the end of her life, Estée Lauder, who stole everything she ever got from Elizabeth Arden, was the most important competitor. For a while, Dorothy Gray was. Yes, definitely competitors, just not the only one.

Laura: I was also thinking about how all of those people you just mentioned—Arden and these other early beauty entrepreneurs—they seem to be larger than life in a way, and I think really captured the public's attention at the time and still to some degree now, like the fact that there have been musicals written about Arden and Rubinstein. I pick up a lot of those old trashy novels from the '60s and '70s that are about the beauty industry or fashion. Charles Revson is a character in almost all of them—a Charles Revson-type person, and I've come across many that have a Helena Rubinstein-type character, et cetera.

Did you notice that she seemed to be this larger-than-life character in the media, in how she was portrayed?

Stacy: Certainly, after a point in her life, it became more common for me to find her in business periodicals like Fortune magazine. I think the second time she was offered a million dollars or whatever for her company, more than a million dollars, that's when I think the male business hierarchy took her more seriously. I think it was about money and longevity. It was easy for them to make fun of her because her ideas were so different from theirs. She didn't attend all the business schools that they went to. They could make fun of her and dismiss her. At the end of the day, all the articles said, “Well, on the other hand, she's still in business and she's making all this money, so we really can't dismiss everything about her.”

In terms of popular fiction and the popular press, she was less covered in the popular press, but more covered in fiction. I have in the book several examples of folks who wrote her into their novels or plays with her, but I could have thrown in another 30 of them. She really was, in that way, a popular name synonymous with luxury. I think part of the answer as to why this was, is because there were fewer people in the beauty industry then and because she was so unusual. She was a woman in what had become a man's field. It was funny because it really was a woman's field, then it became a man's field, and business has always been a man's field. Even though, of course, there are women in business in every era.

I think it was the fact that she stood out. Unlike Helena Rubinstein, who featured herself in many of her ads—Helena Rubinstein, her picture appears, her sisters' pictures appear, she's there. Arden hardly ever appears. There's a mystique about Elizabeth Arden, I think, that comes with scarcity, but when she does appear, people really flock to see her. Then unlike Rubinstein, Elizabeth Arden really does become a synonym for luxury. It's just a stand-in word.

When your name becomes synonymous with something else, you can say a name and I think it stands in for a whole bunch of stuff we think we understand. I think that was true of Arden. It probably became a little more true after the war because more people came to know her because of the work she did with the women and that news traveled. Women wrote home to their parents, parents told other people. It was in newspapers.

Laura: That makes sense. You write about how all these people described her as very feminine and delicate. How much of that do you think was true? How much do you think was a self-creation to go along with selling this idea of feminine beauty?

Stacy: We'll never know, of course, but what do we know? We know that she was born working-class and had very little money, but like lots of young women at her time, she went to the cinema. She saw those glamorous women on the screen. She read novels. Then there were fan magazines that came out about the movies. She saw these emerging celebrities and came to understand beauty in a certain way, I think. Everyone said she was beautiful. Everyone said she had incredible skin. Everybody got her age wrong. There's something about that, I think, that helped her.

Then I really do believe, as I wrote in the book, that she consciously studied the women she wanted to serve. She listened to the way they spoke and she took elocution lessons. She watched the way they dressed and she tried to copy their sartorial choices. She understood that they went off to holiday in Bar Harbor and Martha's Vineyard, so she went off to Newport and opened these little pop-up stores. I think she studied folks. This, I think, is also part of a really good entrepreneur, which is know your customer. What does your customer want? I think since she always aimed at elite women, to model herself on elite women would increase the trust that her customers would have in her.

How much of this is created? My gut feeling, Laura, is almost all of it. The pink protected her in a business world increasingly filling with men. It made her stand out, but it was also…The patriarchy still meant while they could criticize her, they still opened the door for her. Maybe it was a way to deflect the animosity coming from men in the industry.

I teach a course on the history of first ladies, and we were talking yesterday about Jacqueline Kennedy, and I assigned my students the video that Mrs. Kennedy did walking through the White House to show off that. The students afterwards, they're like, "Who would take her seriously with that kind of a voice?" I'm like, "Oh, who took her seriously? Everybody did. We copied her. I mean, she was Jackie Kennedy." That's the same kind of voice that I'm guessing Elizabeth Arden had, breathy, the pauses.

I'm certain that the few times that people suggested that Elizabeth Arden was a little bit ditzy is because she needed glasses, as I put in the book. She could not read the radio script, kept messing up, so when her friend gave her her glasses and said, "Put these on," Elizabeth Arden aced it. I think there were like three decades of women in America walking around into walls because we didn't wear glasses because “men don't make passes at girls who wear glasses.”

The breathiness, the lack of glasses, the makeup, the skin, the paint, the perfume, I think partly it was that she knew she'd be her own best salesperson if she looked the look, partly I think it was a way to make her customers have greater faith in her because they saw her as one of their own, and partly I think it was probably a deflection or a way to deflect whatever animosity was coming from the men.

Laura: I always think it's interesting when you can start peeling someone back and realize how much of the public identity was a self-creation and how and why they did that. That all makes sense from someone who came from a poor background, that she would have had to construct this from the ground up. What do you feel is her legacy?

Stacy: I can tell you that I think what she did was to open doors, not just to other women in the beauty industry, which she certainly did because she launched a lot of careers. She launched careers of fashion designers and haute couturiers. She launched careers of women who had trained with her in publicity and in marketing, and they opened their own businesses and they wrote books and so forth.

She launched a lot of careers and she pushed a lot of women ahead. She hired tons of women at every level, paid them extraordinary salaries. Then they took what she taught them, because she was big on training, and then made careers of their own. She opened a lot of doors for a lot of people inside her industry, but I think she probably opened doors for the women who came to her as customers and clients. I really believe it's not an overstatement to say that since so many women look to Arden for Arden's new definition of beauty, that she changed the lives of women globally, really.

Arden's definition of beauty was, I would say maybe in a couple of sentences, truly countercultural. Because in 1912, '13, '14, when she was introducing makeup, that was countercultural, but she saw how women just glowed with this minimalist makeup, but it was a little bit of oomph, and a little more self-confidence it gave women, particularly as the type of lighting was changing. That was countercultural. Then when women really embraced makeup, every class of women embraced makeup, and the Flapper comes around with the brighter colors and the circles of rouge and so forth, Arden maintains the Arden look, which is still minimalistic and sophisticated and elegant, so then she's countercultural again.

I think it's interesting to think about her as a trendsetter, certainly. Again, is that a legacy? I think it's easier for me to talk about what she really did than what her legacy is. Like I said earlier, everything Estée Lauder did, down to the pink, came right from Elizabeth Arden. Estée Lauder is still with us, the Elizabeth Arden name is still with us. It's a longstanding company or at least brand. To create that brand and to do it so successfully should count for something in terms of legacy. What do you think her legacy was?

Laura: I would agree with all of that, yes. I think probably the biggest element, beyond the fact that the company still continues, is making makeup acceptable for women of all classes. Also, bringing into the public consciousness the idea of a holistic approach to beauty, bringing in exercise, and all of those other things you mentioned earlier. I think she did figure out a way, through all the different aspects of her business, to contribute to much more than just the face and make-up in a way that maybe not everyone's aware of, but they're aware of the trickle-down from the people that she gave opportunities to.

Stacy: That's a good way to put it. You wrote about Maine Chance twice—none of what's happening today [in terms of spas], I think, would have happened had Elizabeth Arden not opened Maine Chance. We should probably throw in the luxury spa as part of her legacy.

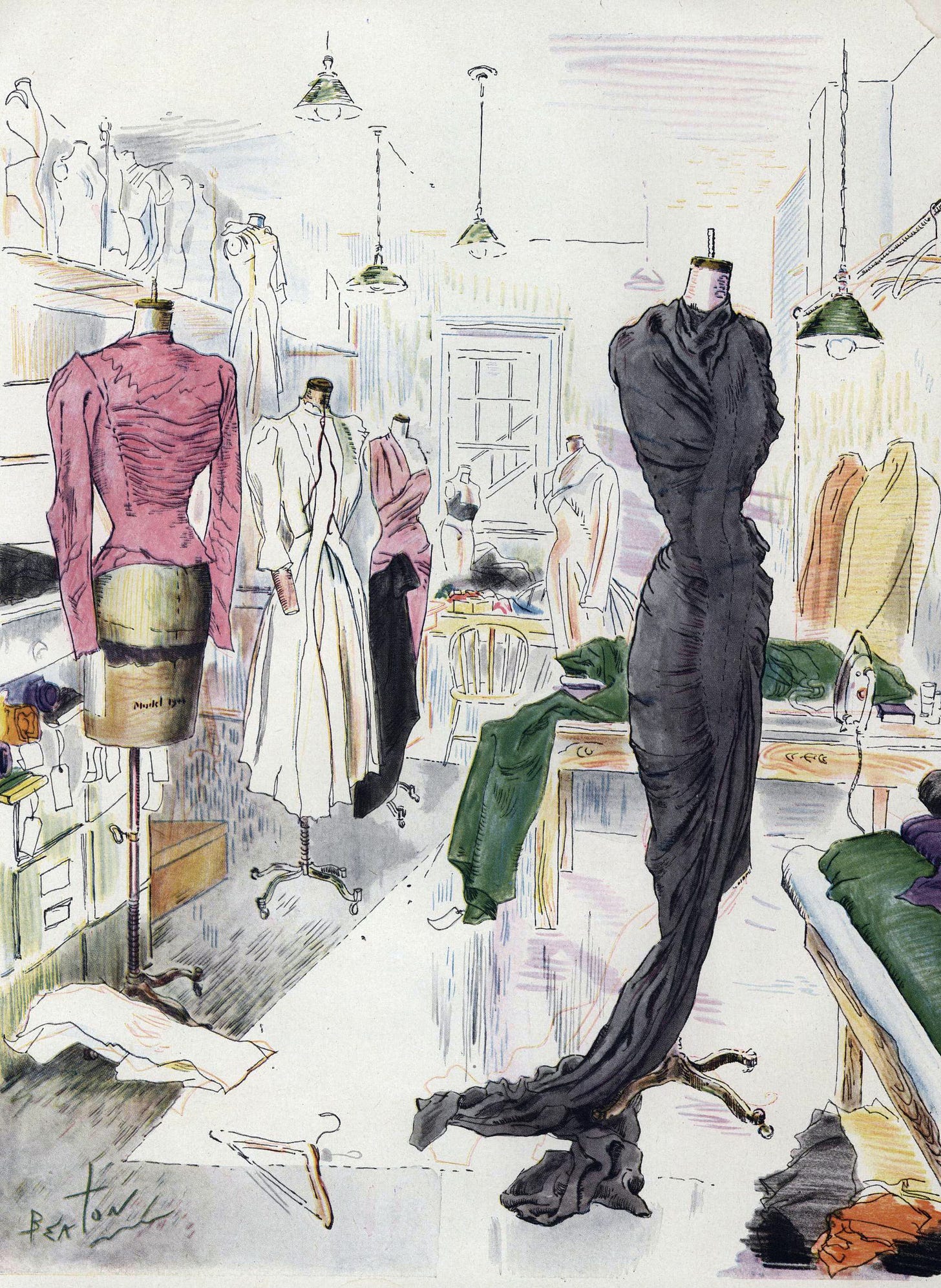

Laura: Totally, yes. I think it's fascinating that she then went into clothing as well. I hadn't realized quite how early she'd gone into selling lingerie and things in the salon but having Charles James work for her and all these other designers, in a way it seems like a jump from the face and the body, but in the end, it is the continuation. What did you think about the fact that she went into fashion, and how do you feel that fed into her world?

Stacy: I think that was helped along by her sister in Paris [Viscountess Gladys de Maublanc], who was really tuned in to the world of haute couture. When Paris was overrun, when the Nazis took over, I think it was clear to everyone in the industry, and you could see this from reading the Fashion Group newsletters, it's really clear that folks in Paris are really worried about this. What will happen? Should they keep producing clothing, extraordinary one-off pieces? Should they do it? Could they do it? If they did it, who would they be doing it for? Because your average Parisian woman wasn't going. You'd be only serving Nazis. Did you want to do that? On the other hand, you don't want your workforce to lose its skills. The discussions happening among fashion capitals, they were dire. People were really worried about this and really concerned about the moral and ethical side of this. Okay, all that, but we have to keep our spirits up.

I think conversations between the sisters probably played a role in Arden's true awareness of what was happening, not to mention that she did, like Helena Rubinstein, go to Fashion Group meetings. It became pretty clear to a substantial number of fashion insiders that Paris could only do so much. It became really clear, abundantly clear to American boosters that America, where the bombs weren't falling, could be the place. "Oh, this will just be temporary. We'll just shift the capital here," but there were always people going, "No, this is going to be a forever change." I think Arden was very happy to be a part of that.

I think she had already had success in her salons, as you mentioned, with certain sweaters or unique pieces or the lingerie, and I think it was a very short step for her to begin to sell these. By that time, her clientele already consisted of minor royalty and of celebrities in America and wives of wealthy businessmen and so forth. I think it was a wonderful nexus of the need to protect the industry from the Nazis and opportunities for American industry here, and Arden believed she could sell it. If she didn't think she could sell it, she wouldn't have tried it.

I didn't write about all of Arden's failures. There were more failures, but she had very few of them compared to her successes. Clothing in this way, particularly high fashion, was definitely a success of hers, so I don't think she saw it as a very far step. I also think since she was a female CEO and owner of her own company and had amassed a fair amount of money by the time World War II broke out, I think she was also interested in wearing those fashions. It's not like they were foreign to her. She was also happy to wear these designers and then happy to sell them. They're a little personal. Certainly, the capitalist in her head was going, “Yes, I can make money here,” but also I think some boosterism all played a role, and certainly Gladys's concerns about her friends who were designers getting their work shown. A lot of it started as fundraising too for the refugees and so forth in France.

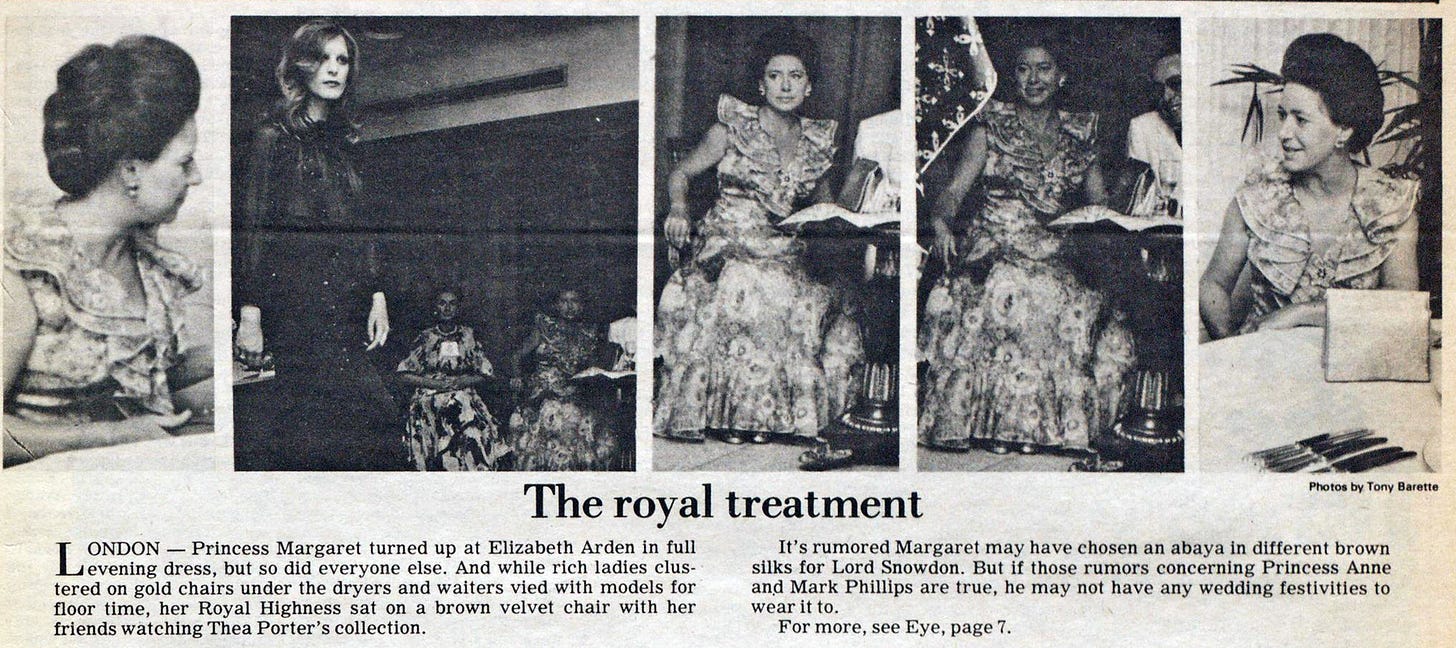

Laura: It must have been a huge success and continued to be a success—I wrote a book about a designer who had an exclusive contract for a bit with Elizabeth Arden's salon in London in the mid-'70s. It's after Arden’s death [in 1966]. Thea Porter had her own shop in London, but Elizabeth Arden from 1972 to 1975 had the exclusive for London other than Thea's shop. They would do shows that Princess Margaret came to there. [Selling fashion in the salon] continued to be a big enough business that it was supported up until the '80s.

Stacy: Again, synonymous with luxury. Princess Margaret shopped there, Jackie Kennedy shopped there. All these fashion leaders shopped at Elizabeth Arden. You knew that if you needed a gown for whatever event, Elizabeth Arden would have something for you. I think partly what happens is that by the time we get to the '80s, those sorts of events have begun to dwindle in our culture, so less of a need for floor-length gowns in the 1980s.

Laura: How did you approach researching and writing—organizing your research, writing the book, that part of it?

Stacy: Every single biography I write, I begin with the primary sources. I start by seeking out primary sources wherever I can find them, and I file every primary source in a folder by date. I write the first draft of every book only on primary sources. Only later do I go to the secondary sources. I don't want anybody else's ideas to influence mine. I want to tell this story as close to her story as I can make it. That's the easy thing to answer. It's all in chronological order. I just literally put them in order, and then I open the file and I start writing. Then I do a lot, a lot of editing. Then I bring in the secondary sources. At that point in time, I have to go, "Oh, well, now I need to find this. I didn't know that happened," or “somebody said this happened, let me go check it out.”

Oftentimes, there are more primary sources connected to things I didn't know about or didn't know as much about, so I just then begin to weave it in. The first draft is always just based on primary sources and then secondary sources and then a lot, a lot of editing.

Laura: How long was the whole process for this book?

Stacy: This book, it got interrupted by COVID, so if you take those couple of years out, it may be five or six years.

I enjoyed getting to know Elizabeth Arden, and I enjoy writing biographies because people fascinate me. The combination of this working-class girl, young woman, from Canada who managed to then, by the end of her life, win the Kentucky Derby, have tea with the Queen Mother, have her name be synonymous with a level of luxury that must have been beyond her wildest dreams when she was a kid; how you get from here to there, that's really interesting to me. How much of it is drive, and how much of it is luck, and how much of it is circumstance, and how much of it is “the steel fist in the velvet glove,” which I do think was very much Elizabeth Arden, that to me is an amazing story.

I really am sad that Arden does not get taught in business schools. Because I think she's got a lot to teach about marketing and sales and product promotion, but also product selection, and a staying true to your own sense of your vision. Because people could not shake her. Her husband could not shake her from that. Other advisors would not shake her. Henry Sell, whom she trusted, couldn't shake her. I think she's a really nuanced story that ought to be told in business textbooks.

She should be in that pantheon of American capitalists, I really think so, and she's not, at least not yet. For all these reasons, beauty, and fashion, and horses, and business, in addition to her own personality and choices, she was rich, I think she's a fascinating individual to study. I enjoyed writing about her. I did. She's not a saint, God knows, but she was interesting.