Welcome to all new subscribers! Substack featured my newsletter on their homepage this week—I hope that you enjoy my missives on fashion and cultural history! For more, consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work and receive all newsletters.

I was recently interviewed about my cats for The Wildest, where I talk about how I got my nickname and Instagram handle, Laura Kitty.

As I’ve spent three newsletters discussing Revlon’s marketing and advertising campaigns from the 1930s through the early 1950s (one, two and three), I’m going to change tack a bit here. This is my last article on Revlon for the moment—I will likely revisit it in the future, but I have a backlog of research on other subjects that I would love to share with you. I began writing these in response to the news of Revlon declaring bankruptcy; instead of writing a broader history of Revlon (which would really require a book’s worth of words), I’ve focused on short time periods and specific time periods—small elements that contributed to the long-running success of the brand.

The House of Revlon was to be icing on top of Charles Revson’s business. In the intervening years since Fire and Ice, Revlon had reached even greater heights of profitability by sponsoring the TV gameshow The $64,000 Question from 1954 to 1958; while it increased sales by 50% and profits tripled, by making Revlon into a more mass-market brand it also lost them much of their prestige—especially once the show became embroiled in a fixing scandal. Revson wanted to use these high profits to re-elevate the brand, to bring it back to the “class” his early ads had sold. To do this, he decided to build the most magnificent salon of all—as Andrew Tobias put it, it was to be “a beauty salon to end all beauty salons he hoped would guarantee Revlon a place alongside Rolls-Royce, Patek Philippe, and Chivas Regal”1—or at least elevate him to the more rarified realms of his chief competitors, Helena Rubinstein and Estee Lauder (for more on the astrology behind their rivalry, read this article). He told the press it was “an attempt to bring about a new ideal of beauty.”2 For others, it was more “an imposing monument to himself and to the cult of beauty.”3 Legend has it that when Helena Rubinstein returned from a trip in Europe and saw it from the window of her limousine, she remarked to her personal secretary, public relations aide, bodyguard, and social director Patrick O'Higgins: "Why, Patrick, you naughty boy. You didn't tell me the nail man had erected his own mausoleum."

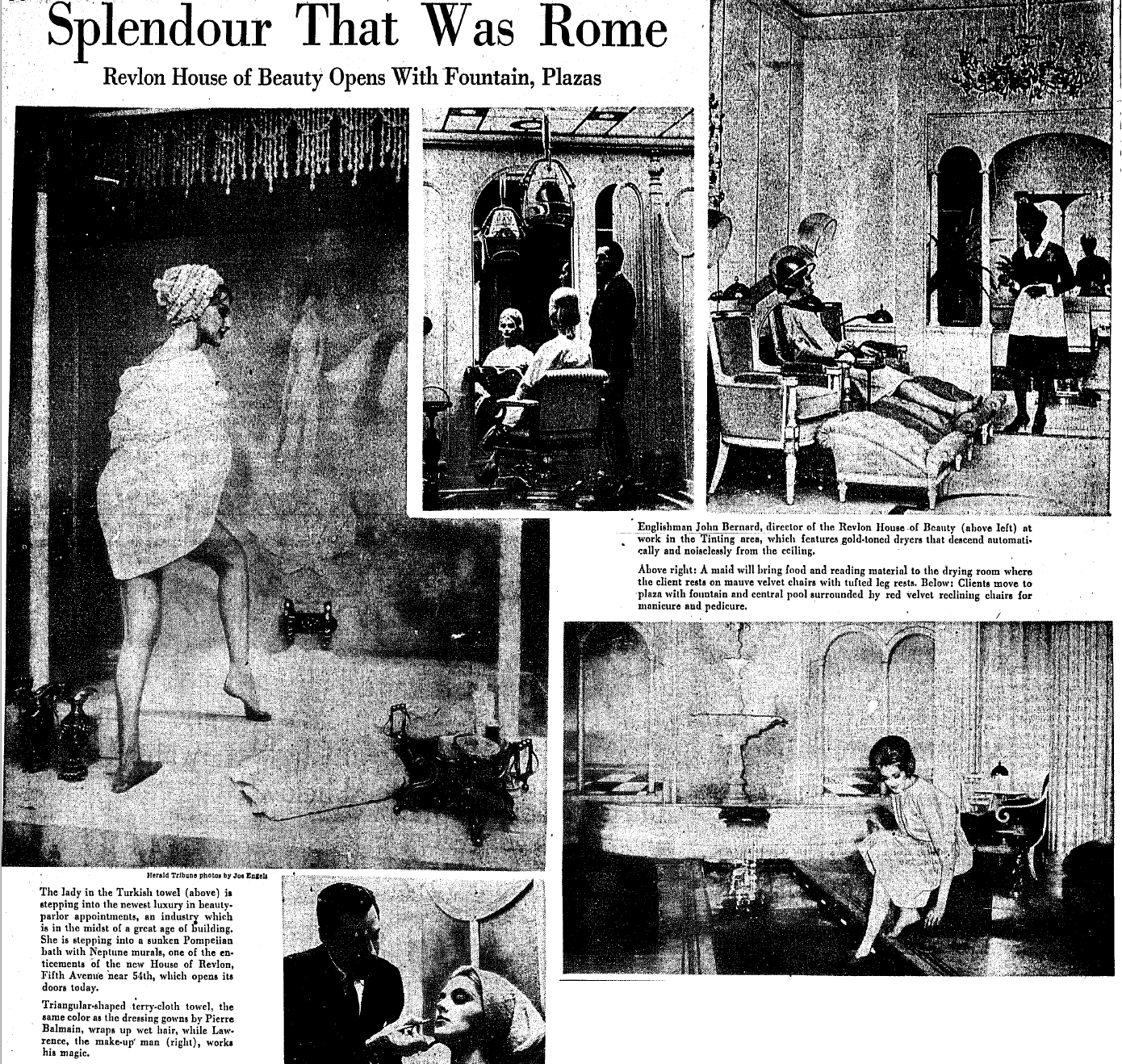

Created to directly compete with Elizabeth Arden’s famously red doored salon (691 Fifth Avenue) and Rubinstein’s (655 Fifth), Revson located his just down the block on the second floor of the Gotham Hotel (698 Fifth, at 59th). Work began in 1959 and ran for almost two years, before the salon opened in early May 1961. This was no small project—and with a perfectionist like Charles Revson in charge, it became even larger. Walls were built and torn out three times before he was happy with the soundproofing—and then torn out again three weeks before opening, as he’d decided some of the work areas were too small and needed to be refigured. Of the construction, the Chicago Daily Tribune newspaper reported: “The technical problems of autonomous heating, out-of-this-world lighting, draft-free air conditioning and floor supports that can uphold a long blue tiled pool fed by hundreds of gallons of water (scented, of course) from a three-tiered fountain probably set technical men screaming for tranquilizers.”4 At the time of opening, the cost was quoted as $750,000 (that’s $7,432,550, adjusting for inflation).

It was truly over the top in every possible way. The theme can best be described as Pompeii by way of the Louis’s. The interior decorator Barbara Dorn was hired to create for Revlon “a beauty salon that represented the ultimate in luxury, tranquility and service.”5 According to one report, she was responsible for “planning right from the plumbing to the final ash tray” (a period essential).6 Dorn traveled all around Europe, collecting antiques and fabrics for Revson’s bricolage offering to the god of luxury. The lighting was by master light designer Abe Feder, who had recently designed the lighting for the Kennedy Center and Broadway’s My Fair Lady and would later be known for “virtually created the field of theatrical lighting design and was also a seminal figure in architectural lighting.”7 For one make-up room, Feder devised lighting that could duplicate daylight, dusk, candlelight, etc. to ensure their clients would always look their best.

With special permission from the Fifth Avenue Association, a large marquee of Tiffany Glass, projecting 18 inches over the sidewalk and sloping to the third story, was built over the doorway—providing a monumental effect to the entrance. Glowing day and night with 60 pink cold cathode tubes, the glass canopy was framed by large squares of black onyx, rising from sidewalk level to the third floor. A display window was to the left of the door, and afixed on either side were “three handsomely wrought bronze lanterns branching from center stem of imposing scale.” When a woman arrived she would push open the “handsome, heavy” glass door—actually, she wouldn’t as the door was found to be too heavy for most women so a doorman was hired—and emerge into a fantasyland:

She steps first into a cosmetic boutique, its carpet of gold, its walls gold and white, its chandelier a vast cluster of crystal fronds, veined in gold…In the rear is a jewel box of an elevator paneled in cerise cut velvet, fresh flowers nodding from old fashioned limousine vases on its walls [according to Tobias, “Installing the elevator was a problem because the third floor, to which it ordinarily would have been anchored, was off-limits to Revlon, and that meant breaking down the wall into the Gotham Hotel kitchen”].

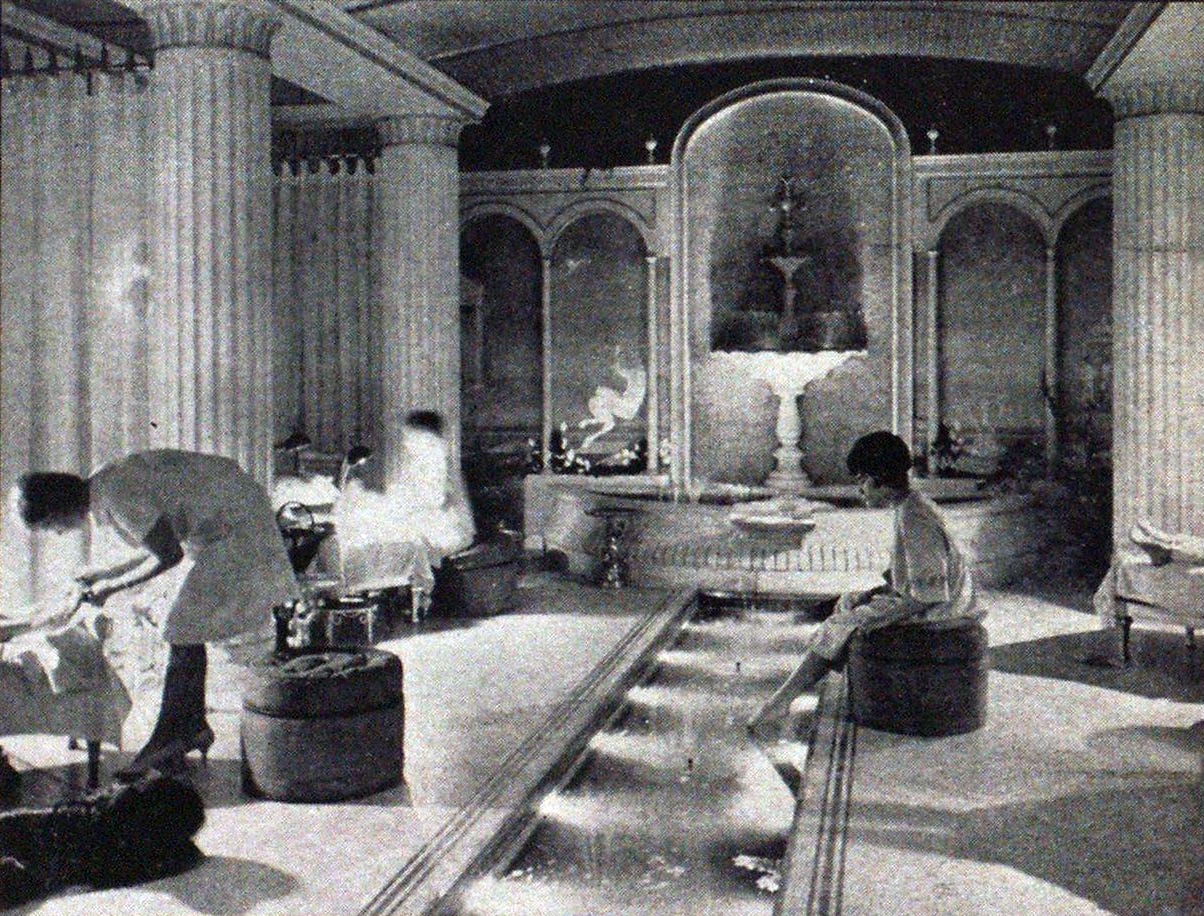

The second floor is Pompeii revisited. Radiating from an oval reception area—called the Atrium —is an appointment desk tented in silk, beyond that a tantalizing glimpse of the pool and slender columns of a Pompeiian plaza; and on the other side, tinting and drying areas that make the heart stand still—and will make beauty salon history.

In the dressing room, its walls patterned in lavender, there are no cubicles. Privacy is elegantly preserved behind French screens paneled in blue velvet on one side, mirrors on the other. Maids dressed in pale gray, their skirts bouncing over crinolines, their little aprons gray striped in white, hang clothes and furs on satin covered hangers, hand the client a pink peignoir (by Pierre Balmain), a little pink basket bag and golden [plastic] sandals. The basket is for cigarets, note paper, the key for the private steel vault in which she locks up her purse or any emeralds or diamonds she might be wearing that day.

Two sumptuous bathrooms adjoin this area: one has a circular shower, its jets golden rosettes, its walls gold and ivory mosaic tile. Down a columned corridor is a sunken Roman bath, 8 feet long, 4 feet wide, with golden swan-head faucets. Behind the heavy doors of this marble retreat one can have a milky foam or a sulpher bath.

Want a “Touch of Genius” manicure? Glide to the Pompeiian room with its twilight lighting, its long, fragrant pool; recline on a rose velvet chaise longue or perch on a silken cushion beside the whispering water.

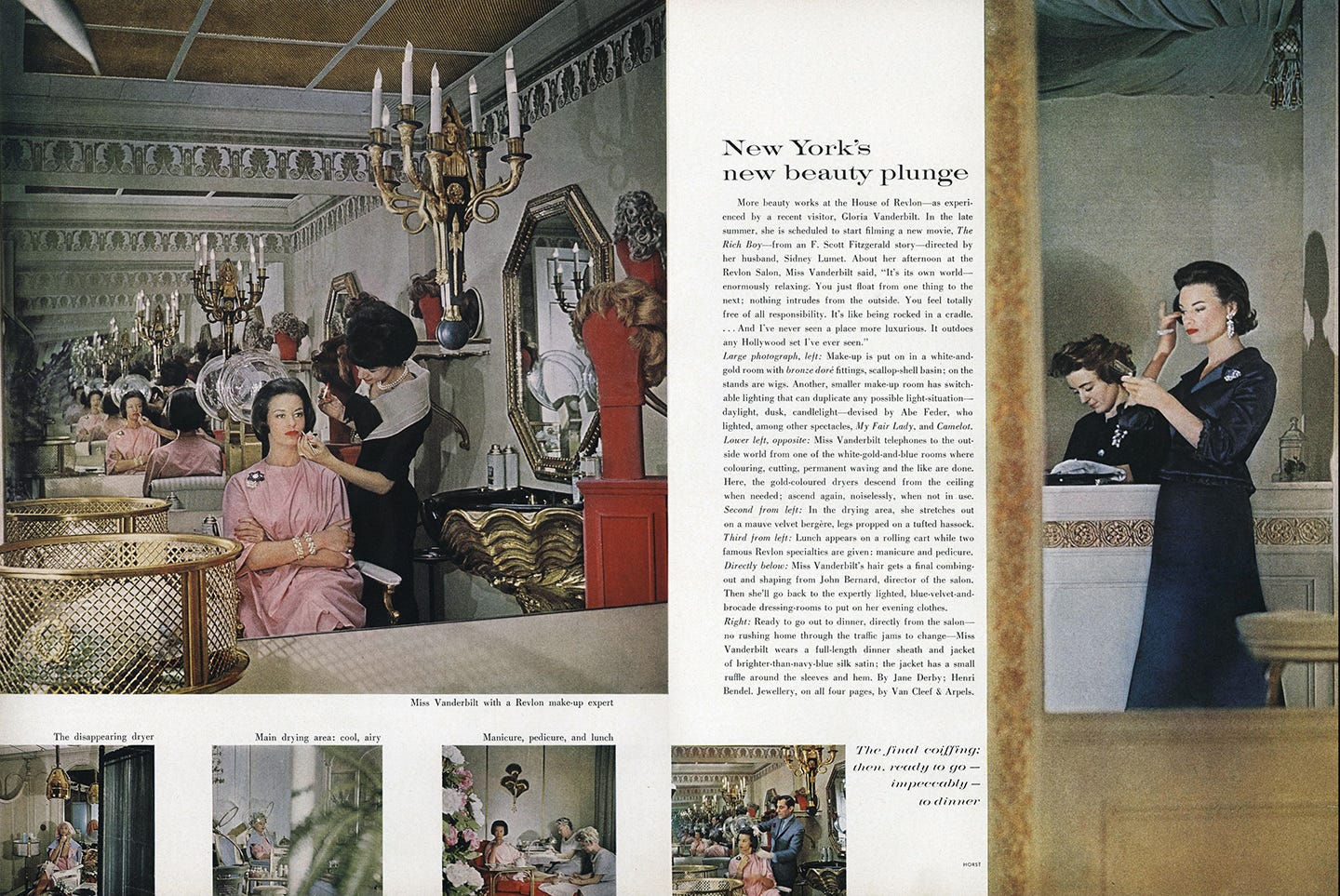

Want a hair styling?... Special spotlighting is focused on the damask chairs, custom designed; shampoo basins are upheld by gilded, cast bronze swans. In one drying area chairs are lavender velvet with matching tufted ottomans sloped to relax leg muscles.

Want a tint? Here the bowls are gilded bronze conch shells lined in black marble, on dolphin bases, the lighting is superb and gold plated dryers telescope from the ceiling, where they look like inset fixings when not in use.8 [Tobias: “In practice, there was the problem of keeping the patroness positioned so that the descending drier would encompass, not cleave, her head. The driers were left down most of the time.”]

Returning to that Pompeiian whirlpool bath, Tobias wrote that it was “so large it took twenty minutes and 196 gallons of sea water, scented water, sulfur water, or milk to fill. Naturally, it had to be drained and cleaned after each use, so only six or seven, baths could be performed in one day. When it became apparent that a woman could fall asleep and drown in such restful surroundings, a maid had to be hired to lifeguard.” Supposedly one woman tried to take her life in the other bath but was quickly saved by one of the multi-purpose maids.

Revson’s choice of a Pompeiian interior calls to mind the early twentieth-century vogue for antiquity-inspired architecture and locations. I talked some about this in my earlier articles on Henry Erkins’ interiors for Murray’s Roman Gardens and Café de l’Opera, both extravagant lobster palaces that lit up Times Square around 1910. This interest in Imperial Roman architecture in turn-of-the-century New York went far beyond eating establishments—just look at Grand Central Terminal (1913), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fifth Avenue facade, 1902), the New York Public Library (1911) and the original Penn Station (1910), which was based on the Colosseum and the Baths of Caracalla. Lobster palaces—so called due to their lavish late-night menus of lobsters and champagne—were known for their ostentatious, over-the-top interiors, permissive atmosphere, and late-night dining. Murray’s Roman Gardens, Café de l’Opera, and Rector’s Pompeiian Room all drew from the architecture of the ancient world to create immersive dining experiences. While they might have had one era that they proclaimed they were replicating—whether imperial Rome or Pompeii—these places were more a hodge-podge of ideas from many civilizations across many centuries. The same could be said for the House of Revlon—pseudo-Pompeiian mosaics and Roman baths interwoven with Louis XIV, Louis XV and Louis XVI furniture

Whether one was going for a midnight meal at Murray’s Roman Gardens or spending a day at the House of Revlon, the purpose of the interiors was the same: to transport the customer away from the grime of New York and situate them in a liminal space separate from their day-to-day life, in order so they could completely relax. According to the restaurant designer David Rockwell (the visioner of Planet Hollywood and Nobu, among hundreds of others): "Theming is just another word for evocative design that is narrative and transports you to another time and place… When you have a limited amount of time and only so much disposable income, you want to go places that are meaningful, places that touch a nerve and create an emotional response."9 It should perhaps come as no surprise that in the first decade of the twentieth century, many Roman-style public baths were built—the most lavish of which was the Fleishchman Baths, a replica of the Baths of Diocletian that filled 20,000 square feet at 42nd Street and Sixth Avenue. Exclusively for well-to-do New Yorks, “Fleischman's 'Roman' facilities included a tepidarium, a calidarium, a steam room, a natatorium or plunge pool, a shampooing room with marble compartments where bathers were scrubbed and scraped, an electric light bath (cabinets containing a hundred electric lights, to ‘stimulate all the vital forces’ and help ailments caused by ‘nervous exhaustion’), gymnasia, dressing rooms furnished with divans, a massage room for rubs with oils and perfumes, pedicure and manicure departments, barber and hairdressing salons, a solarium which contained a tropical garden with trees, plants, flowers, statuary and birds, a restaurant, and a grill”10—a true predecessor of the House of Revlon; a full escape for the senses in an ornate, other-worldly interior. Interestingly, none of Revson’s competitors went the same route for their salon interiors—perhaps only Revson’s ego reached such Nero-like proportions.

As Revson told Harper’s Bazaar, “I meant, of course, to create elegance. I believe all women want it, need it and deserve it. But the cherished feeling they find in the House of Revlon does not result simply from its luxurious décor. The enhancement of beauty has much more basic origins. The talent of experts accounts for it, the quality of our preparations accounts for it, and absolute devotion to the client. These make beauty come true.”11 Charles Revson hired the best-of-the-best hair stylists—all temperamental stars like himself, all with devoted clients already. John Bernard was salon director for a while, fresh from running salons in London and Paris; Filippo of Rome came over twice a year, in addition to keeping the salon stocked with his “marvelous hair pieces.”

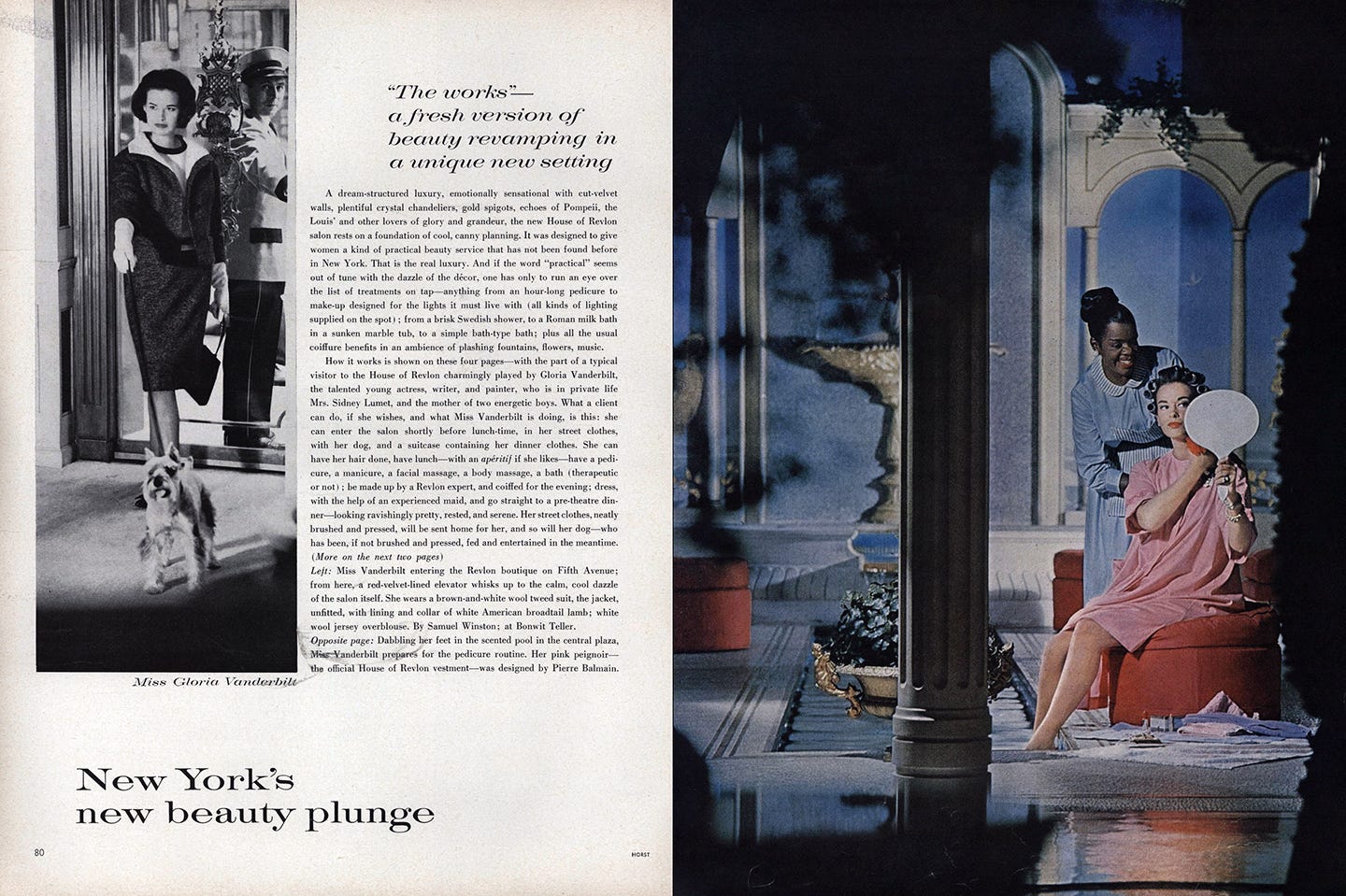

Vogue published a four-page story with a young Gloria Vanderbilt (at the time Mrs. Sidney Lumet) play-acting a day at the House of Revlon. For Horst’s camera, Vanderbilt took on the role of a client arriving “at the salon shortly before lunch-time, in her street clothes, with her dog, and a suitcase containing her dinner clothes. She can have her hair done, have lunch – with an aperitif if she likes—have a pedicure, a manicure, a facial massage, a bath (therapeutic or not); be made up by a Revlon expert, and coiffed for the evening; dress, with the help of an experienced maid, and go straight to a pre-theatre dinner—looking ravishingly pretty, rested, and serene. Her street clothes, neatly brushed and pressed, will be sent home for her, and so will her dog—who has been, if not brushed and pressed, fed and entertained in the meantime.”12 The photos reveal room after room of gold trim and ornate details, with staff waiting on her hand and foot. At least according to these images, the maids appear to be Black and the cosmetologists, receptionists and hair stylists white—a clear division of labor between work that would have been considered unskilled and skilled.

For all the outward success the House of Revlon projected, it was plagued by constant problems. Within weeks of opening a heatwave knocked out the salon’s custom-built generator. With the AC out and no water running, employees had to take water from “the pedicure pool to rinse the suds out of their clients' hair, and then send them home in mid-beautification.” Another generator was flown in from Detroit, but such were the types of problems that continually popped up. Revlon charged premium prices that were around 20% higher than their competition, but this was not enough to cover the costs of the luxurious service nor the perpetual issues (add in that many alimony checks from divorced clients bounced and it was quite a mess).

Due to rising costs, such luxurious salons had been money-losing operations for even the most well-known since around 1945. Revson had wanted the salon not to make money, but to show that Revlon was a luxury brand—he had the mass market, yet he wanted high-class prestige too. When it proved to be a difficult project to maintain at a high level, he gradually lost interest in it—instead putting his focus on a high-end skincare and cosmetics line (Ultima, later rebranded to Ultima II). The House of Revlon maintained its luxury service and socialite clientele throughout its lifetime, but in 1972 it closed with no fanfare nor notice in the press. I’ve had no luck finding out what happened to the House of Revlon’s interior when it closed—no mentions of a sale or demolition. His direct competitors Helena Rubinstein passed away in 1965 and Elizabeth Arden in 1966. Following her death, Rubinstein’s company decided that her salons were costly liabilities rather than assets, and most of them were closed. Arden’s Red Door salons continued in various iterations until filing for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in March 2020. The building that housed the House of Revlon and the Gotham Hotel has been the five-star Peninsula Hotel since the late 1980s.

The influence of the House of Revlon and the earlier lobster palaces can most clearly be seen in the themed hotels and spas that crowd the Las Vegas Strip. Caesar’s Palace, the Bellagio, the Venetian all operate with the same vision: to transport customers away to a made-up world of illusion, promising magic and intrigue in much the same way as a lipstick advertisement.

Andrew Tobias, Fire and Ice (New York: Warner Books, 1976), 236. All other quotes that are not footnoted are from this biography.

“The Ideal is Beauty,” Newsweek, May 29, 1961, 64.

Eleanor Nangle, “Pompeiian Styled Salon Is Ultimate Beauty Service,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 23, 1961, B5.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Barbara Dorn One Of Nation’s Most Successful Decorators,” Naugatuck Daily News, November 2, 1960, 3.

Mel Gussow, “Abe Feder, Master of Lighting in All Its Forms, Dies at 87,” New York Times, April 26, 1997.

Nangle.

Michael Kaplan, Theme Restaurants (Glen Cove, NY: PBC International, 1997).

Margaret Malamud, “The Imperial Metropolis: Ancient Rome in Turn-of-the-Century New York,” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics Vol. 7, No. 3 (Winter, 2000), 74.

“Beauty in the Making,” Harper’s Bazaar, October 1961, 149.

“New York’s new beauty plunge,” Vogue, August 15, 1961, 80.

I absolutely LOVED reading this article…it took me away! I’m looking forward to reading/re-reading the Revlon articles, too.

I was born and raised in San Francisco and I remember the fanfare and decadence of the cosmetic and beauty salons of department stores (I was born in 1963). The one that stands out in my mind was I. Magnin! I.Magnin (Joseph Magnin store was a bit more “mod”) took my breath away as a little girl, entering at street level and descending into a huge, marble filled, gold, crystal area with counters as far as the eye could see. The smell of perfume…everywhere! It was so “grown up” and magical for a little girl! What wonderful memories (with my grandmother)!