Revlon I: The Early Ads

Since the announcement of Revlon filing for Chapter 11 last month, I’ve been thinking quite a bit about Revlon, its co-founder Charles Revson, and its many peaks and its coming disaster. Below is a short overview of Revlon and their early, ingenious marketing strategies; follow-up deep dives on their color promotions, “Fire and Ice,” and the House of Revlon salon will be sent out over the coming weeks.

The history of Revlon and C.R.’s life was well-told in Andrew Tobias’ Fire and Ice, published in the same year as Revson’s passing in 1975, but the full story of Revlon since then has not been told. Tobias’ biography looks like it belongs in this newsletter—the metallic title and illustrations of gorgeous women give a sense of a trashy novel, not serious non-fiction. While often written in a gossipy tone, this is a pretty no-holds-barred business biography—Tobias seeking to get to the root of Revson’s personality, digging through the prostitutes and affairs, to find such a workaholic that the biography ends up a primer in running a cosmetics company from the ground up. If you are not interested in the history of fashion and cosmetics businesses, it’s probably not the book for you—but if you do like reading such things (especially with an added dash of salacious content and remembrances from bitter ex-employees), then it is a great end-of-summer read.

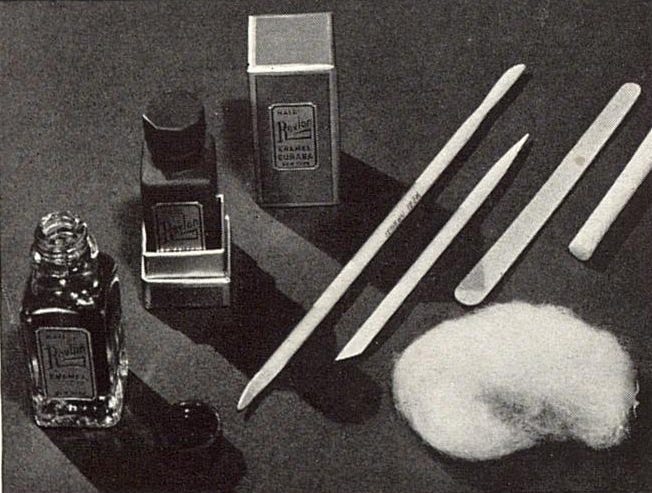

Charles Revson founded Revlon alongside his brother Joseph (their other brother Martin joined in 1935) and chemist Charles Lachman in 1932, exclusively making a novel opaque crème nail enamel—the chemistry stolen from Elka, a nail polish company that Charles worked for as a sales rep. At the time, coloured nails were associated with “actresses and prostitutes,” and all nail polishes on the market (other than Elka) were transparent, made from dyes that only lightly covered the nails in differing shades of red (light, medium, and dark). Charles Revson realised “cream enamel,” made from pigment so that it properly covered the nail, was a revolutionary beauty product. From the first batch, Revlon produced their nail enamel in a much wider array of colours than ever available on the market before. C.R.’s genius wasn’t just to make lots of shades of opaque varnish—it was to figure out a way to market it to women to make it a beauty essential. For decades he focused their sales on beauty salons, with Revson learning how to give and teach a perfect manicure using Revlon enamels. He showed manicurists just how superior their enamel was (and it truly was), leading every salon to order it—then later he made most salon customers sign exclusive agreements so there would be no in-salon competition. “What better advertisement than to have Revlon used by the professionals? What more ideal arrangement than to have women pay to have ten samples of the product painted onto their nails, to be shown around town for the rest of the week?” Once women became used to the glamour of long, Revlon-coloured nails, they began to ask their department stores for it—opening another huge market for them in 1937. By 1938, Revlon was a multi-million-dollar company.

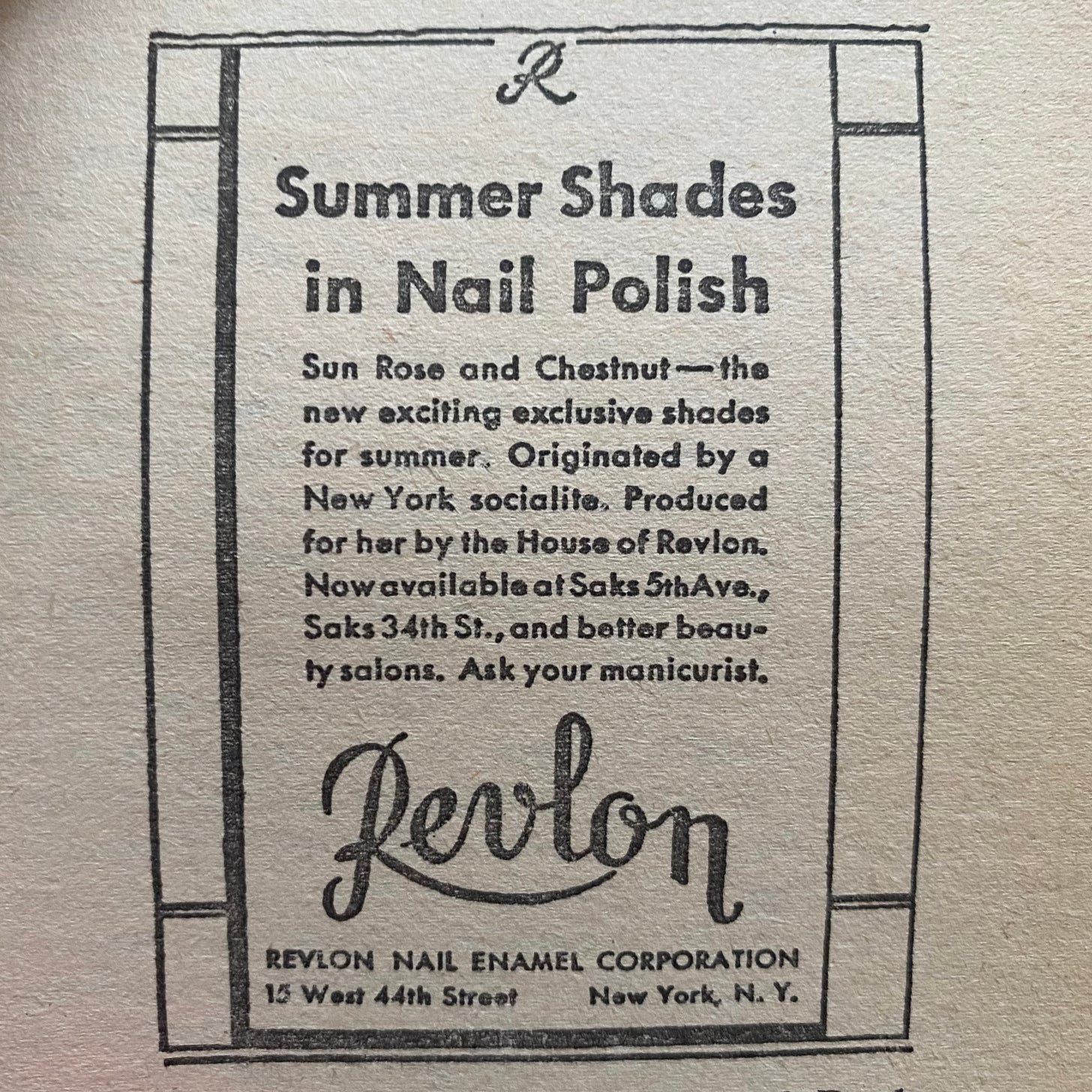

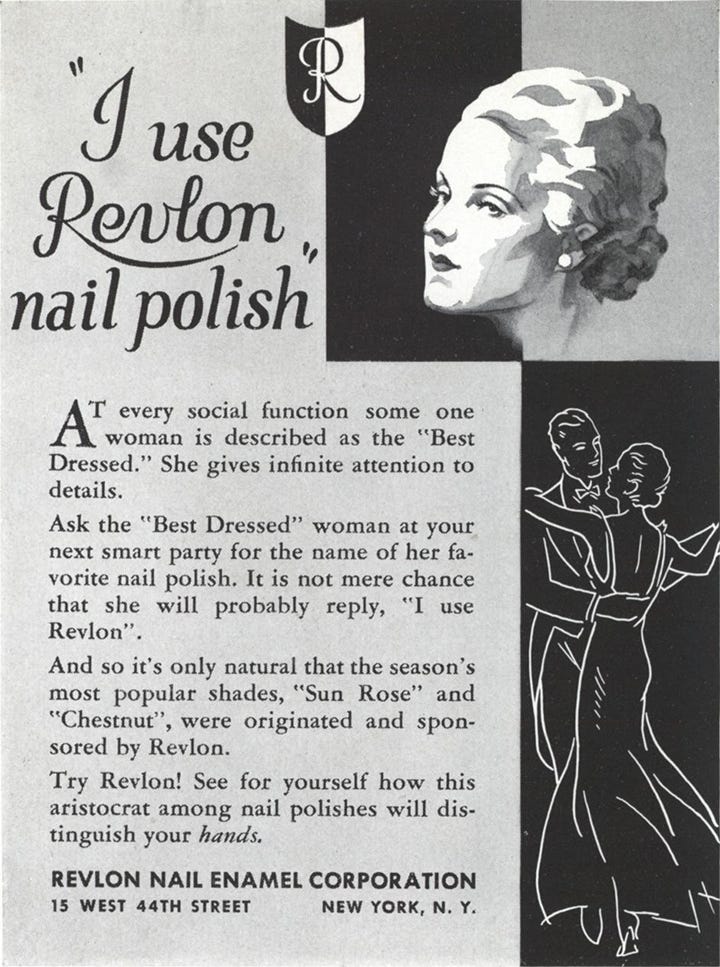

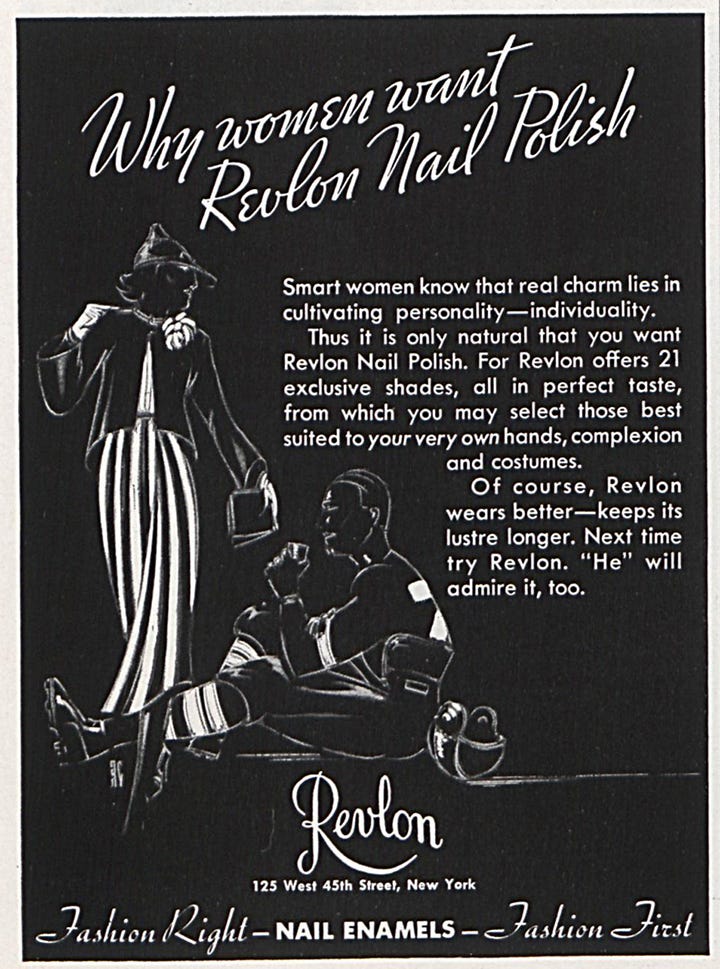

The earliest Revlon ad I know of is the above, published in The New Yorker in the summer of 1935 (and reprinted in Fire and Ice). In the words of Tobias, “The New Yorker… The House of Revlon… a New York socialite… Saks Fifth Avenue. It’s the image that counts, never mind the fact that ‘the House of Revlon’ was a few bare rooms where people poured from big bottles into little ones and trimmed applicator brushes; or that Charles didn’t even know a New York socialite; or that that ad, which cost $335.56, was Revlon’s total consumer advertising budget for the year.” What was important was portraying the idea that high-class women wore nail enamel—Revlon’s nail enamel. An ad in Vogue the following year reinforces this idea: “At every social function some one woman is described as the ‘Best Dressed.’ She gives infinite attention to details. Ask the ‘Best Dressed’ woman at your next smart party for the name of her favorite polish. It is not mere chance that she will probably reply, ‘I use Revlon’… Try Revlon! See for yourself how this aristocrat among nail polishes will distinguish your hands.” Even though it was the Depression, Revson chose not to compete on price but only on quality—likewise, his ads did not focus on the material differences of the enamel (their opaqueness) but instead sold the idea of class (not something the poor cigar roller's son from Manchester, New Hampshire, had grown-up with).

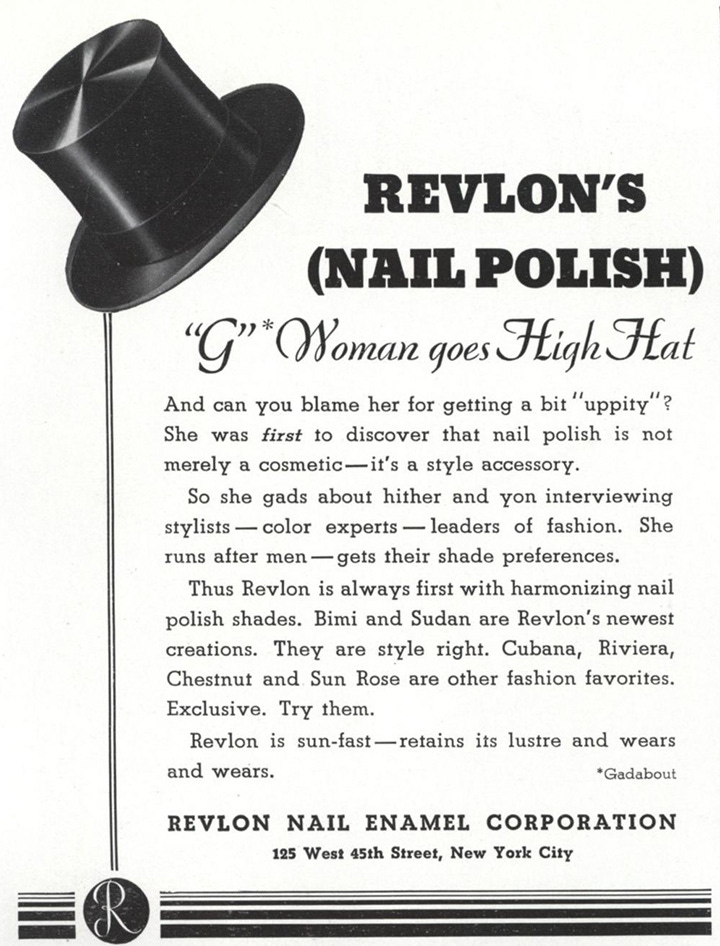

From these early days, Revlon advertised heavily in relation to sales—from mid-1936 on, their ads were consistently in all the major fashion magazines every month. This gave beauty salons and competitors the impression that Revlon was a much larger concern than it was. They borrowed privately for years to not expose quite how modest they were; finally taking bank loans when they were already established and far beyond the point of filling and labeling their polish bottles by hand—actions that they would continue until purchasing some secondhand machinery in 1937, enabled by the success of their products and advertising.

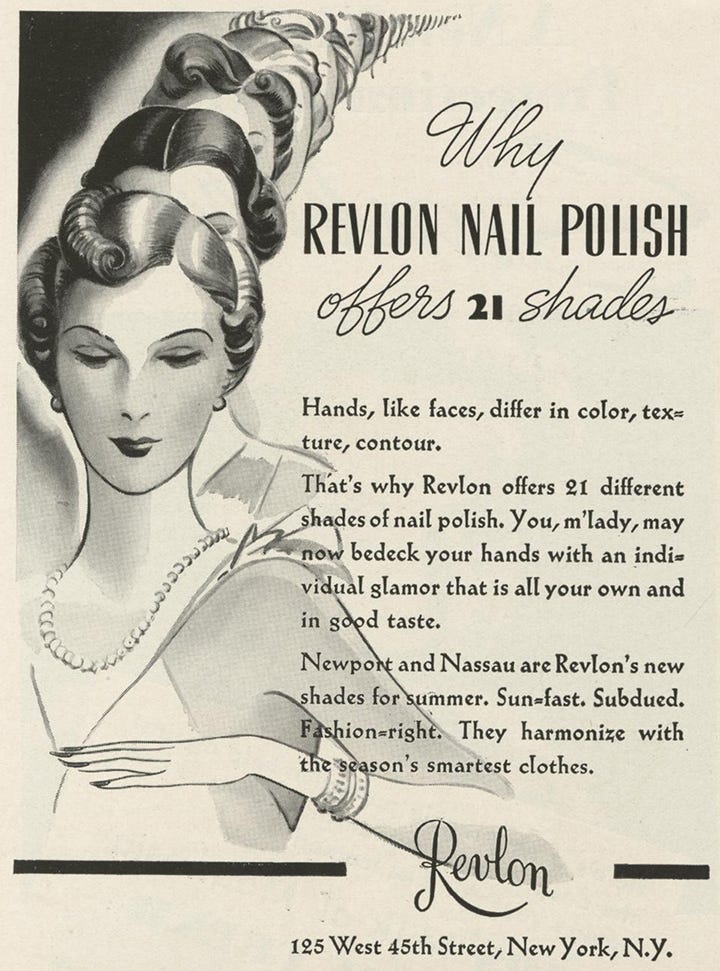

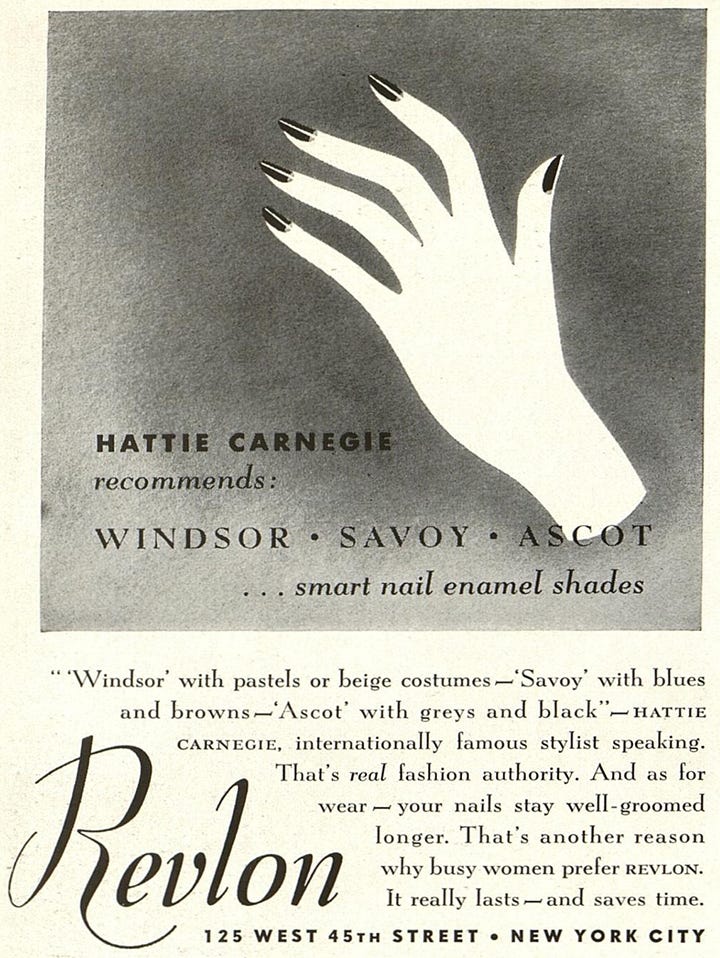

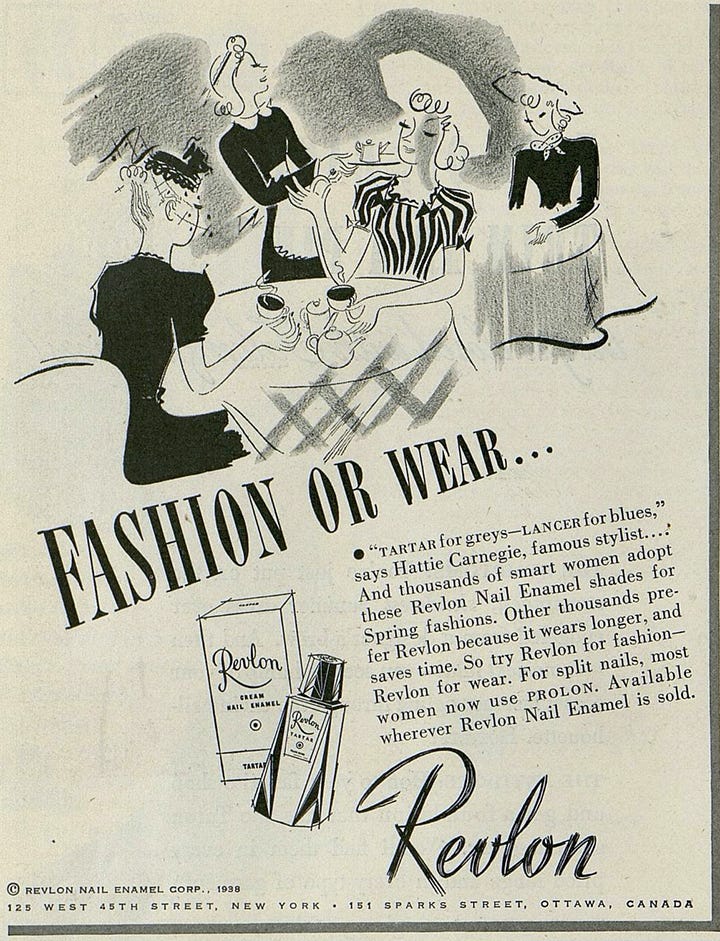

Revlon’s early ads spoke of matching nails to your clothes and to “flatter the individual coloring, texture and contour of your hands.” In 1938, they brought in famed fashion designer Hattie Carnegie to recommend certain color polishes to harmonize with different colour outfits.

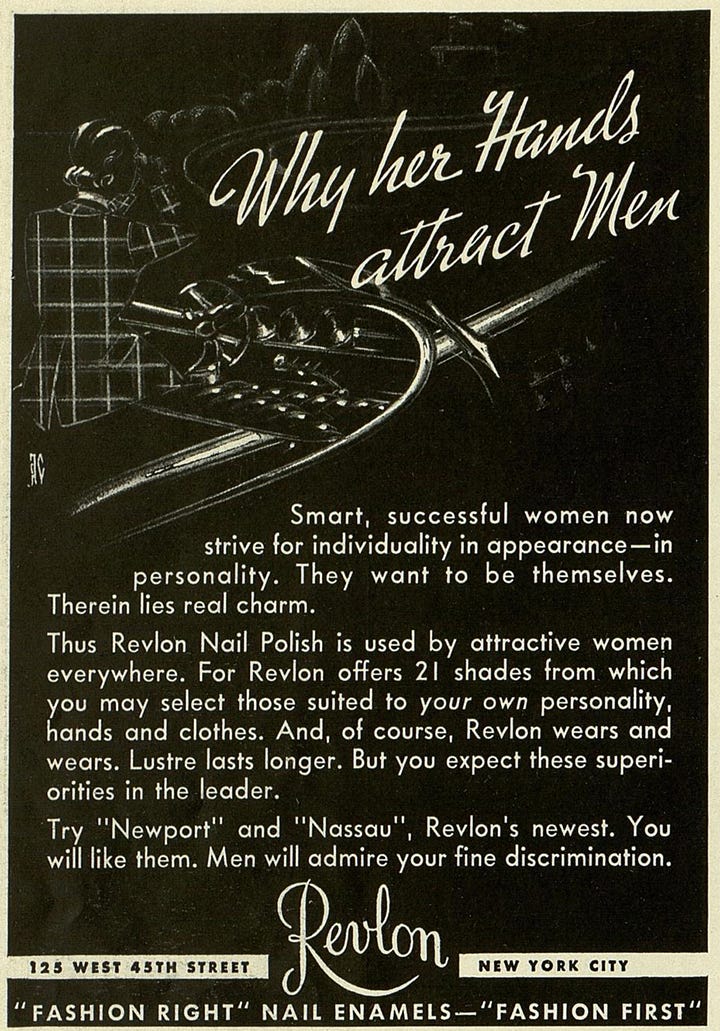

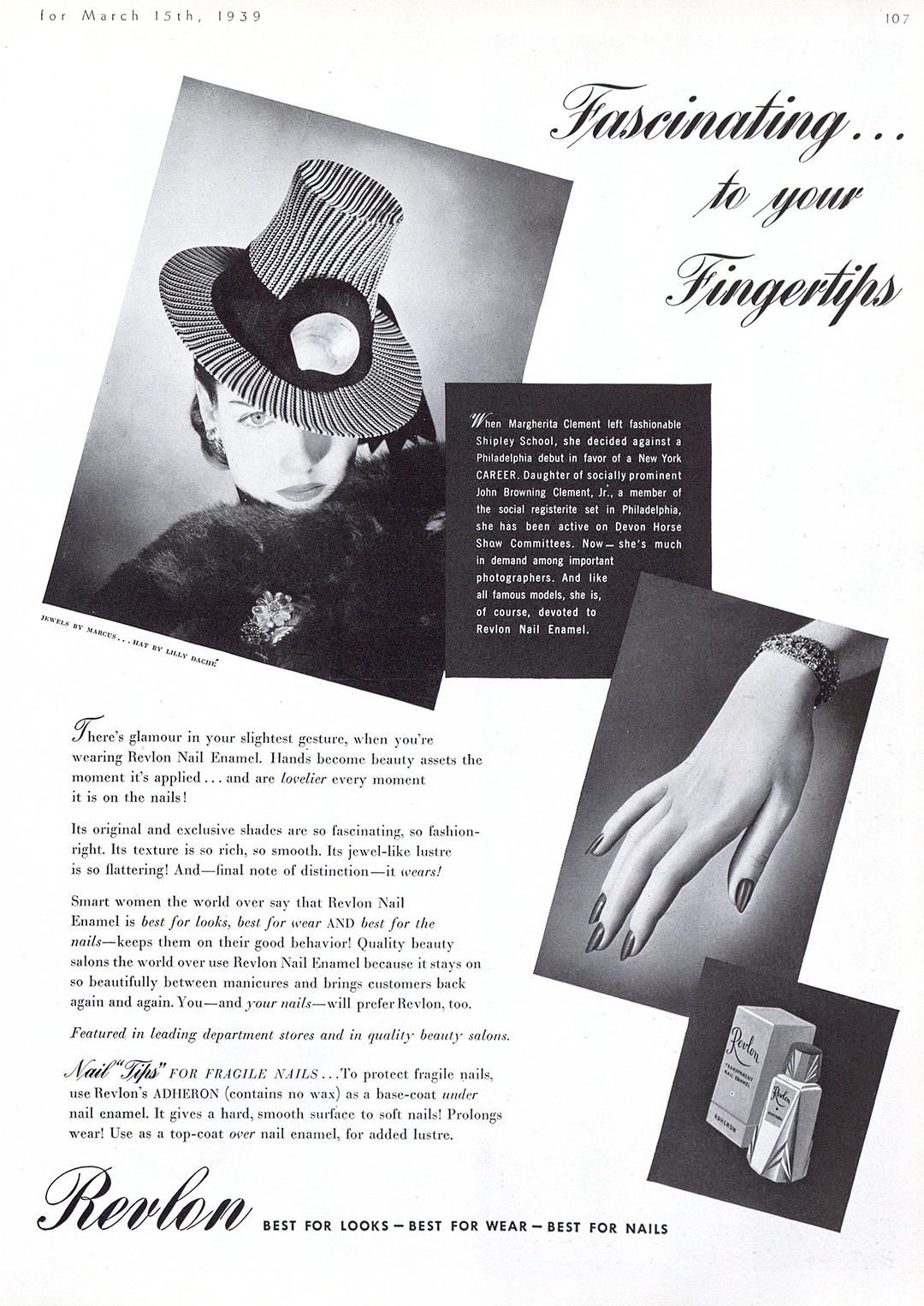

As modeling became a more respectable career, Revlon began to use model’s stories as the focus of their ad campaigns—bonus points if they were both socialites and models, like Margherita Clement, “daughter of socially prominent John Brown Clement Jr., a member of the social registerite set in Philadelphia.” Socialites, “smart women,” models, college girls—all types of women that Revlon used to sell their polishes. The ads might talk of how much stronger their nails were since using Revlon, but the real sell was that beautiful, socially important, wealthy women wore Revlon—and if you didn’t wear Revlon, then your lack of style would make you a social outcast. Also, with their ads reiterating each month that young women from good families chose to color their nails, Revlon furthered the acceptance of it across all groups.

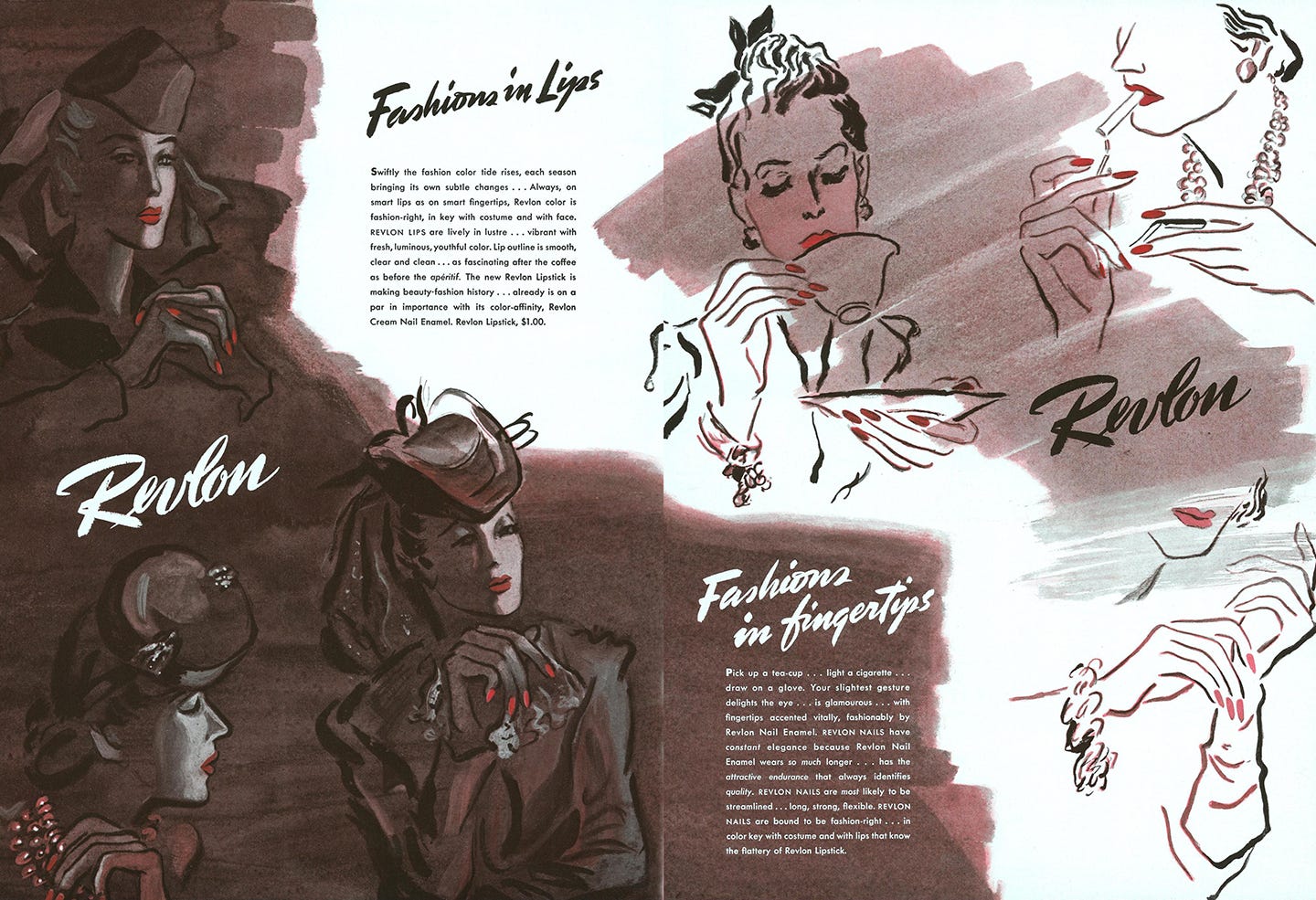

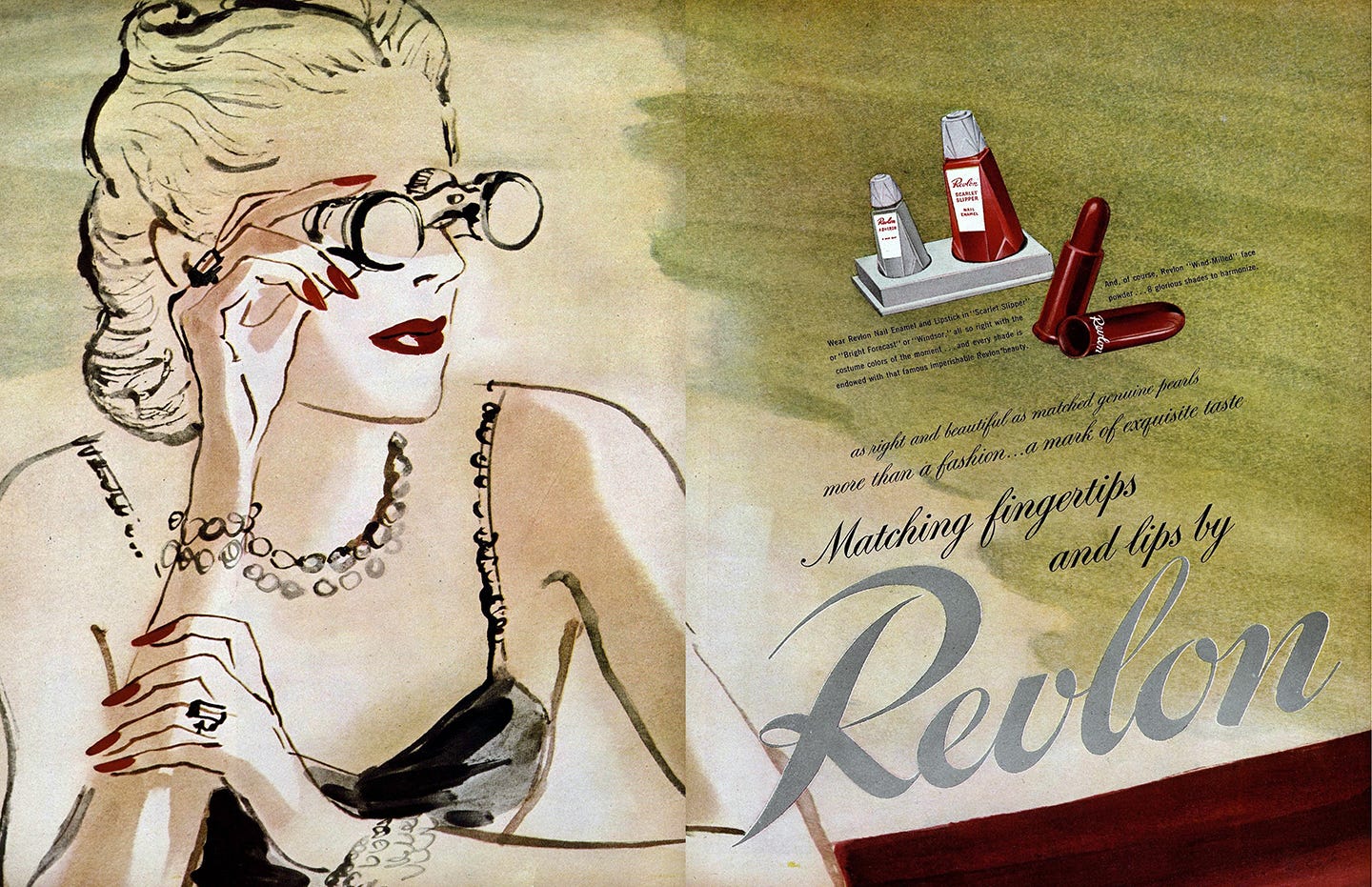

In 1940 Revlon came out with lipsticks in the exact same shades as some of their polishes, setting a trend for perfectly matching the two. As Tobias points out, Revlon wasn’t the first to come out with matching lip and nail colours—Revson copied this idea from another company that had used the theme in their ads a few years previously. But like all genius copiers, he did it better—full colour, illustrated double-page spreads in the glossy fashion magazines selling class for the price of a lipstick: “Always, on smart lips as on smart fingertips, Revlon color is fashion-right, in key with costume and with face...” Matching fingertips and lips were sold as “as right and beautiful as matched genuine pearls… more than a fashion… a mark of exquisite taste.” As new colours were added to their line-up, they were accompanied by colour ad campaigns that vibrantly drew in a clientele already now used to exclusively wearing Revlon on their tips and their lips.

These ads led to the launch of Revlon’s famed colour promotions in 1944—the shade names and their ad campaigns inextricably linked with Revlon and its success. More on those in the next newsletter.

Fascinating! Can’t wait to read part two! Now to get a manicure!