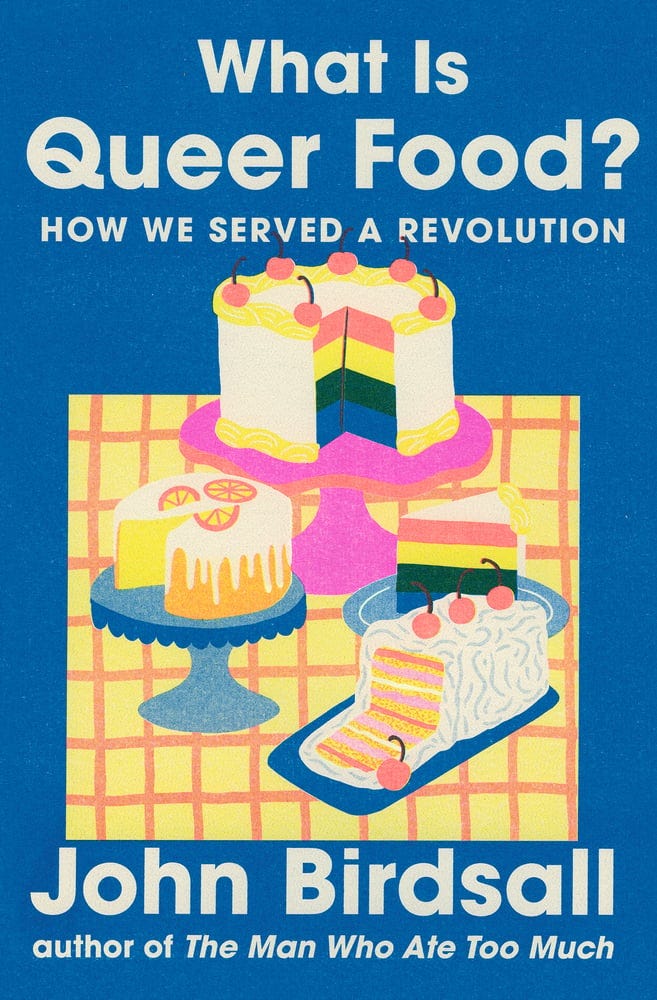

What is Queer Food? A Conversation with John Birdsall

A new book on the queer people who redefined American food

How do you define “queer food”? This is the question food writer John Birdsall contemplates in his new book, What is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution (W. Norton), which was released earlier this week. Mapping a large cast of characters over the course of a century, Birdsall weaves in and out of their stories, in and out of the closet, charting a wide variety of ways that queer people have interacted with food—and through those interactions, have “queered” food.

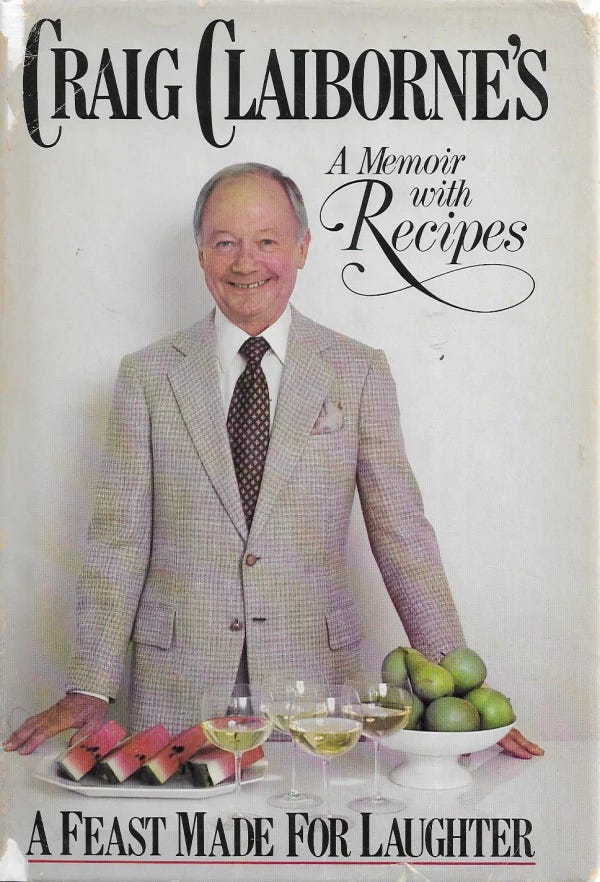

Some of his characters are still famous, significant for their roles in changing how America ate (like Craig Claiborne) or for work outside of food (such as James Baldwin and Alice B. Toklas); while many others never found fame, either in the food world (Harry Baker edited from the history of the invention of chiffon cake) or beyond. Eminently readable, its the kind of book that kept having me pause to look people up—how had I never heard of Esther Eng before!—while also providing much greater depth and nuance to those I thought I knew about.

It’s very clear while reading it that this expertly quilted patchwork of stories are the result of decades of thought—a kind of life’s work, bringing together everything he’s read, researched, thought about for most of his adulthood. And after all this reflection, Birdsall concludes that “there is no essentialized cuisine of queerness, any more than there’s one simple answer for what it means to be queer.” As he lays out in the prologue,

Connecting with food becomes this paradigm for other connections, shared queer food a hinge for the realization of a queer common purpose. This is who we are, dahling. This is how we feed our own. This is how we stay alive.

Food is part of a queer arc of survival, shared sustenance on the path that we and others like us kept open so that others could get safely through. Survival by the oppressed is itself a form of defiance, and the food that fuels it is a means for resistance. Queer food is ordinary food transformed by context, part of a narrative of disobedience, to become something with collective power.

I spoke with John earlier this week about the research and writing process for What is Queer Food?, his background as a chef, the many characters who weave in and out of his book, and much more. What is Queer Food? is now available on Bookshop, Amazon, and wherever books are sold. Subscribe to

’s substack, “Shifting the Food Narrative.”This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Laura McLaws Helms: Reading your book, it really felt like this was the culmination of decades of thought by you. Like you'd been pondering this and slowly tying all of these different things together. Some books you read, and this is the same for books I've worked on myself, you sell an idea, and then you go and do the research, and it's this finite enclosed thing. Then you move on to the next project. This [book] really felt like it was, like I said, everything that you'd read and thought about for decades coming together. Was it like that for you?

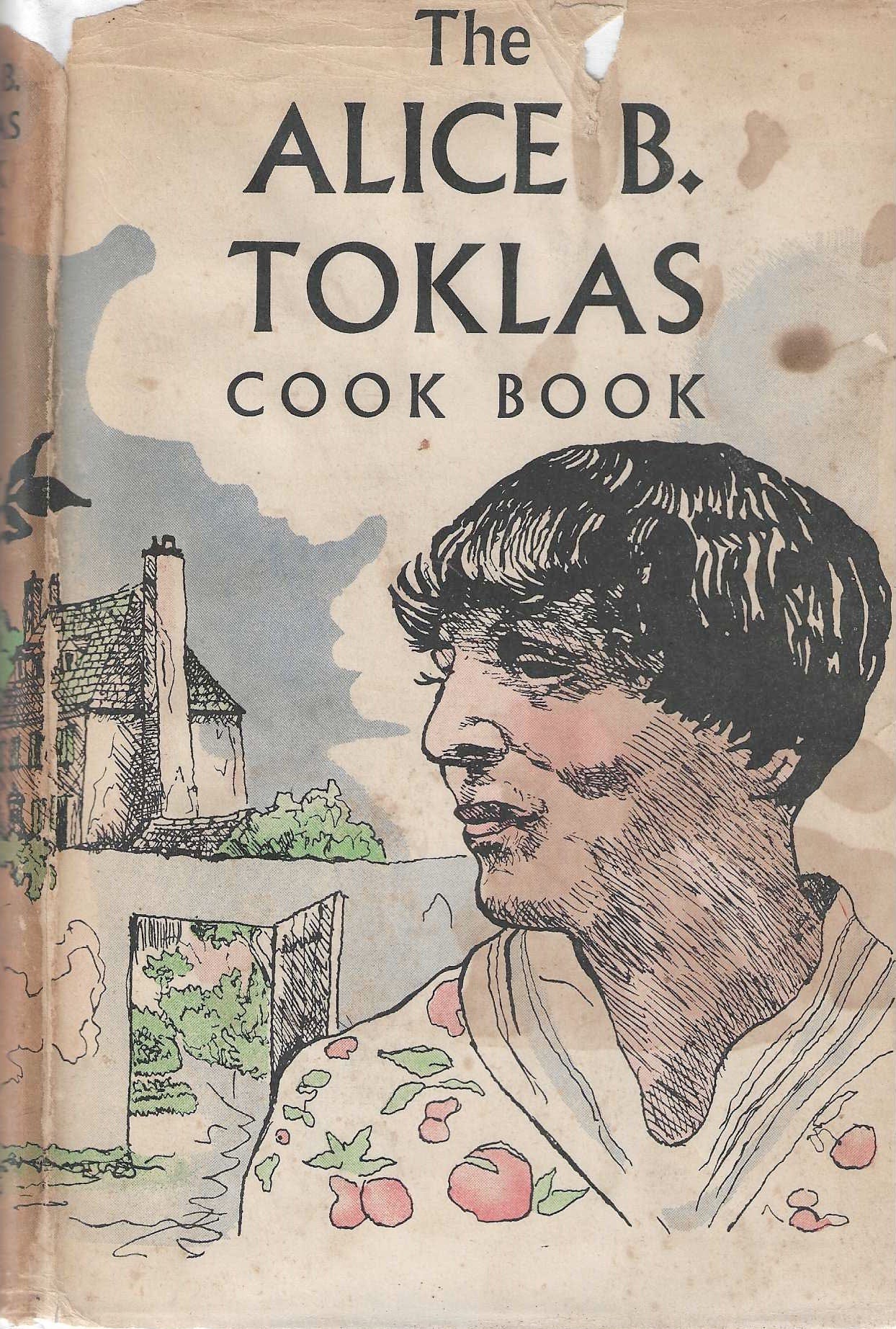

John Birdsall: Oh yes, absolutely. I picked up, especially some of the texts like Simple French Food by Richard Olney, and of course, The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book, probably in 1983 or 1984. They had a very large, heavy impact on me as a young cook and as a young man coming out in San Francisco. They were personal, almost like talismans for me. I had written about them a little bit over the years, but never really knew how to do it in the way that I wanted to. It was such a long evolution, for me, of even becoming a writer, having a voice. Huge respect to my publisher, Norton, and to my editor, Melanie Tortoroli, who actually asked for this book.

I was spinning my wheels with proposals for other things, and she was like, "You know what we'd really like from you is a book about queer food. If you could put all of this into some kind of argument, we would love to see that." What was unstated is that they're taking a chance as a publisher that this book will find its audience. Yes, I feel a little bit stunned that all of these thoughts, as you say, that have been kicking in my brain for so long, finally, have found a place to come out.

Laura: When you first came across those cookbooks you mentioned and as they became talismans, were you already questioning “What is queer food?” Or when did that question become something in your mind to ponder?

John: I have been tracing it back to a comment that an early editor of mine made. In about 1986 or 1987, I was working as a restaurant cook in San Francisco and started to write some food pieces for an LGBTQ weekly in San Francisco that doesn't exist anymore, called the Sentinel, one of three or four LGBTQ weeklies that were being published at the time. They were free papers. They'd be stacked up on the cigarette machine at the entrance to a queer bar. The Sentinel really tried to do arts and culture coverage. It was a new thing to give it seriousness and give it import in a queer weekly, certainly in San Francisco.

I had this editor, Eric Hellman, who challenged me, and he said, "Write about restaurants, do reviews." I did some recipe pieces, but he said, "Is there a gay sensibility in food? Can you describe what that is, what that would be, what that would look like, or taste like?"

If I could put my finger on what a gay sensibility in food would be like, how would I describe it? How would I recognize it? I took that as an assignment. It became a mission, I guess. Even long after I stopped writing for the Sentinel, that question nagged at me, haunted me, because I felt that it existed. I felt that this was a thing, that it was part of our culture, that how the people I knew and the way I was living in San Francisco in the 1980s in very joyful and difficult and tragic times, how food informed our lives and how it kept us together in some way.

That thought paired with my frustration about being a restaurant cook in San Francisco, working with so many queer people in the back of the house, but not seeing that culture reflected in the food that we made, that there was this imposed silence about queer expression, even in San Francisco in the 1980s, even in restaurants that were part of this wonderful wave of Chez Panisse-inspired restaurants that were run by women, it was something that couldn't find expression in the work that we were doing.

I carried that frustration and also that sense of injustice with me, that here we were cooking, really creating the experience of food in San Francisco at the time, but not being fully acknowledged for it. It was very stigmatized, and then, of course, the fact that AIDS was really reframing what it meant to be gay, and was restigmatizing queerness, especially in restaurants.

Laura: What led you to become a chef and then to start writing about food?

John: I got a bachelor's degree in English at UC Berkeley and hadn't ever really thought about food. I had these aspirations to be a writer, but I had no idea what kind of writer I wanted to be. I made no efforts in trying to meet writers whom I admired or even figuring out how to create a career like that. I did get a job right out of Berkeley at this company in San Francisco that published trade magazines. I was a junior editor, rewriting press releases basically. Then, after a couple of years of doing that, I wanted something more. I had met someone who would become my boyfriend, who had been a waiter at this restaurant, Greens, in San Francisco, which still exists.

It's run by this Zen Buddhist group in San Francisco. They had a farm North of the city. It's an amazing moment. He took me to lunch there, and I had this cliched epiphany, I guess, this salad in front of me like, "Where did these greens come from? I'd never tasted anything like that." I wanted to know how it was all done. It really engaged my curiosity. Eventually, I volunteered at the restaurant on weekends, and then they hired me. That really became an apprenticeship, working at Greens, which was a unique place. I was one of the few non-Zen students who was working there, and there'd be these mindful work periods, quiet work periods, where you're just supposed to be extremely focused on your work.

That started me. I figured I would work there maybe a year, and then I would start writing about food after that. I just got captured by restaurant kitchen life—all of those dysfunctional family stories that we've all read and heard. Eventually, after a few years in, I started writing for the Sentinel, writing for this queer paper, but then I didn't leave the kitchen till 2002.

I quit my last kitchen job. I was so broken down just physically. I knew I didn't want my own restaurant. Once you reach a certain level, you're not making any more money. There's nothing you can do. Your body's already starting to just get really tired. I just took a chance. Fortunately, my husband said, just give it a year, see if you can sell stories and I'll pay the bills. It took a couple of years, really, before any story was published, but that began in the local Bay Area, the newspaper ecosystem there and then at the weeklies. That began my career sometimes as a staffer, but also as a freelancer as well.

Laura: Then you did a book on James Beard, right?

John: I did. Yes. The Man Who Ate Too Much in 2020. That really came from the thinking that I had been doing. I wrote an essay, “America, Your Food Is So Gay,” for the print edition of Lucky Peach in 2013. That piece gained resonance, a surprise to me. I won a James Beard award for it. That put me on the map for certain editors of legacy food magazines. I got assignments, and I got an agent. I think my agents and the marketplace were like, "Well, you have success with this essay, ‘America, Your Food Is So Gay’ that takes on James Beard and Craig Claiborne and Richard Olney. Maybe explore that deeper."

I resisted because I wasn't sure that I wanted to immerse myself in research on a biography, but eventually came around to thinking that I did want to write about Beard. There had been two earlier biographies of Beard, but I really wanted to write about his complicated sexuality and how he navigated being one of the best-known figures in American life for a couple of decades really, and how he navigated this private or semi-private life of being gay. That was much more complicated than I anticipated, trying to understand the closet in mid-20th-century America. It's a very complicated concept because he lived in this open secret within New York food, which was a small world.

That led me to feeling like I wanted to say more. I needed to step back. In Beard, I felt like I had been able to drill down into one life. I wanted to step back and look at a multiplicity of lives and look at this period of most of the 20th century and look at what I think is this great story of queerness in the 20th century, which is people figuring out how to claim subjectivity, how to seize the definition of homosexuality from all of these forces who had inscribed what homosexuality was, psychologists, judges, police, popular fiction, all these distortions, and really take that back, and wanted to look at the role of food in this story of seizing that narrative.

Laura: How did you approach researching that when people were living in the closet? The archives omit so much of this, if there's even an archive devoted to these people. So much was left out of their personal letters. How do you approach finding this?

John: Since researching James Beard, I've really seen my work as archaeology, really finding the existing shards and scraps of people's lives and trying to put them together, and then having to speculate on many of the missing pieces. At first, I felt uncomfortable about speculating in that way, but then felt confident that it's really a necessary tool in talking about queer lives. Yes, stories were erased and erased in large part by queer people themselves because obviously, the letters had to be destroyed.

Having lots of experience in food, and of course, as we were talking about before, having thought about some of these figures and these stories for so long, I felt like I could speculate or try to recreate worlds by taking other information, disparate information of the life and times of a figure and introducing them into what likely would have been an experience. For instance, the Sunday potlucks that I mentioned in the prologue, women coming together in your apartments in the early 1950s to listen to The Big Show hosted by Tallulah Bankhead, because there was some connection, some rumor that she may have slept with women, but could still be this huge, radiant star.

Not only knowing that those potlucks happened but trying to imagine what the coffee table would have looked like, what the food scattered around the room would have been, what that experience would have been like. Those details, I've been desperate to know details like that. My writing about this culture of food in queer communities in the 20th century has been really fueled by my curiosity, my need to know what people were actually eating, what the texture of those parties or home cooking were like, what the flavor of those events were like.

Trying to not only say that perhaps a particular party or a particular place like Café Nicholson in New York, that the joyous culture that was recognizably queer took root there, but what it was, what the experience of that was, what the details of that culture were. There were things that I didn't feel that I could recreate, piece together, that I couldn't really speculate on, and other areas seemed like they were rich in supporting materials to be able to describe such things.

I think the Saturday Night Function, the salons that James Baldwin and Richard Olney were part of in 1956, was particularly maddening because I don't believe that Baldwin mentioned them at all. There's a little bit of information from Mary Painter, and Richard Olney talks about them a bit in his memoir. Both Baldwin's biographer and Beauford Delaney's biographer talks about them with whatever information is there. That I think more than anything in my book seemed like a really crucial moment for me, those salons and trying to get that information, trying to imagine what those must've been like. That took a lot of work and a lot of thinking, a lot of poring through Baldwin to see how he was in other social situations, and how he must have been for these events.

Laura: I think you did a beautiful job evoking an atmosphere. With that one, I really got a sense of what those salons would have been like, especially as Richard stepped into his own as a chef, a cook. You really captured an atmosphere for all these different places that I was like, "Oh, I wish I could just go back," especially to Café Nicholson.

John: Café Nicholson, my God. There's very little that we know about Edna Lewis, and what we know about her, what we think we know about her really comes filtered through Judith Jones, those two books [The Taste of Country Cooking and In Pursuit of Flavor]. I think Judith had a very firm idea of who she saw Edna as, maybe who she wanted Edna to be. Looking at the scant available evidence of Edna, it seems clear that even though we associate her with the South and with Virginia and with this lost world of Virginia, Edna surely was so happy to be out of that goddamn place, that place of poverty, that place of no opportunity, that place of no possible expression, personal freedom and artistic life and just finding those things in New York [when she moved there in the late 1940s].

Laura: I thought I knew quite a bit about Edna Lewis from The Taste of Country Cooking and I've been to a few of the Edna Lewis Foundation dinners and things like that, and had, as you were saying, an idea of her, and that idea definitely did not include [her working for the communist newspaper] The Daily Worker. It didn’t include doing windows at department stores. It did not include all of these things that makes her a much more complex, a much more interesting person.

John: There's a woman [Susanna Cuyler] who was trying to do an oral biography of Jeanne Owens, who died young. She was this artist and sculptor, and she'd been a competitive swimmer. Grew up in this privileged way, and went to the Art Students League, and so met Karl Bissinger and Johnny Nicholson and then became part of this circle that Edna Lewis was in.

In Susanna Cuyler's oral biography of Jeanne Owens, she does interview Edna, and this is, I think, in the late 1970s or maybe around 1980 when she's doing this work, but just getting those little details like Jeanne went to Paris and brought back a jar of gazpacho for Edna Lewis to taste. Just that idea that Edna Lewis was teaching herself how to cook in this idiom that would have been completely new to her, and that she was piecing [it] together and that she probably couldn't even taste in restaurants in New York City. Being a young Black woman, even if she had the money to go to a place, she would not have been served there. That was a really tantalizing thing.

As I say in the book, I wanted to not only focus on queerness as just an easier term for LGBT, this blanket umbrella term, but something that means more, something that means that is not about some sort of simple gay/straight binary but can have a more complicated and nuanced understanding. I always use that quote from bell hooks, defining her own queerness as constantly, constantly having to push back against these forces, this killing, normalizing, this sense of power overwhelming you and not wanting to hear from you, but this idea that you take that and you create new forms, and that's what I found reading whatever was available about Café Nicholson.

Johnny Nicholson was just inventing—with very few means—really inventing this magic. Obviously, it turns into something else when it becomes celebrated by this fashion magazine world of New York City and theater world. It also makes me think of something Ocean Vuong has said about how a lot of people, when they realize they're queer, it feels like a diminishment, like your life is going to be diminished in some way or be difficult in some way, when in fact, he realized that it opens up this completely inventive world to you, that it's an enhancement of your life. I wanted to express that, especially in talking about Café Nicholson.

Laura: The book is structured in these very short chapters, almost like vignettes. You're going in and out between characters. They keep reappearing. How did you approach writing that?

John: It was more, I think, intuitive. In the past, I've felt a lot of power from assembling a mosaic of different stories. This is maybe a bit more braided, braiding in different stories, having people come in, sometimes slight connections, like Craig Claiborne and Esther Eng. I felt because the ambition was so wide to tell this sweeping story over several decades, it had to be made up of a multiplicity of moments and stories and voices. I did not want it to be academic in any way. Not that I don't have tons of love and respect for academic works, but I didn't want anything as stayed as formal chapters. I just wanted it to be more fluid throughout.

I had written the Beard biography as really a traditional chronological biography, and after it was published, I regretted that. I know why I did it because, partly, I didn't have confidence as a writer. We had sold the book that way, but I think especially telling a story, as some of the stories in What is Queer Food? and also about Beard himself, the darker parts of his personality, his sexual abuse of young assistants, that yes, I think it's more powerful to weave different strands in that might be roughly chronological, but not having to strictly adhere to that.

Then throughout, I felt I didn't want it to be a one-note optimistic story of, "This is how we all became free as queer people." I was conscious of using Craig Claiborne's story, weaving Craig throughout as maybe a tragic story or something that was real to a lot of people, especially men in his generation, and trying to navigate power and having a place in the world while being deeply conflicted about his sexuality or private life. I felt like I needed to snake darker stories of Craig throughout this narrative and how Craig made a choice to reject moments in his life where he could have gone another way, where he could have embraced who he was, but chose not to.

Laura: I grew up seeing Craig Claiborne's cookbooks on my mother's bookshelf and also my grandmother's, along with Richard Olney's and James Beard's, and without having any sense, obviously growing up, of what their personal lives were like. Even though I have [Craig Claibourne’s memoir] A Feast Made for Laughter, I've never actually read it. As you were spooling out both of their stories, Richard and Craig, it was really illuminating and illuminating about the background behind these men that were very influential on the way that my mother and my grandmother approached cooking.

These are nice upper-middle-class white ladies, and these are the men that they're looking to for advice, yet they have these whole other sides to them that wasn’t spoken about. I'm sure my mother knew that they were gay, but it wasn’t talked about. [Reading What is Queer Food?] felt like opening a door into something about my childhood. I've read a lot about how America changed and became interested in food, particularly after the '50s and '60s, but adding the queer angle and understanding that there was this whole secret world that they were subsuming into the food and into their dishes was really illuminating.

John: Just in ways that they could, within a very conservative publishing world—especially cookbooks, very conservative—subvert traditional gender, just by, like Beard, writing cookbooks that aspire to be everyday cookbooks. Of course, there was a tradition of men, and even Claiborne falls into that, of cooking in this occasional way, where you made these grand, deeply flavored dishes with blue cheese and lamb or whatever, but your wife would be doing the daily cooking. Either these gourmet bachelors would make this grand weekend food, or in this really creepy tradition of male cookbooks in the 20th century about cooking to seduce women.

To have somebody like James Beard, who was like Ina Garten to us now, someone who would inevitably be turned to for the Thanksgiving story in Good Housekeeping. There were all kinds of ways that he would have to be framed [to make him acceptable as a cook of everyday food]. He’d have to be this jolly tweed-wearing, bow-tied uncle. It's fascinating to me how publishing dealt with that coding and how they created, I think, layers. I even suggest in What is Queer Food? that even Craig's collaboration with Pierre Franey was somehow acceptable, if this was the food of a male French chef, and not some pansy in the kitchen, but this had a masculine reason for being.

That idea that everybody knew, of course. Of course, our mothers would have known or strongly suspected, but I'm sure would not have wanted to really think about James Beard's private life. That was all part of it. I did want to introduce that underexplored idea of Julia Child's homophobia. Thank goodness that Laura Shapiro investigates that in her biography of Julia Child [Julia Child: A Life]. How, even someone who was quite liberal, otherwise, like Julia, and who, although she disavowed 1970s feminism later, but really someone who was a feminist figure in that world, who was doing things that a lot of people hadn't seen women do before, and did it with a forceful bravado. Her persona was always a blend of traditional feminine qualities and traditional masculine qualities. That's what makes her so wonderful and fascinating, but for her to really be the voice of these really unshakable rules in the 20th century, like "Yes, homosexuality exists, but it must exist in this way over here. It must not come up at dinner parties."

As someone told me when I was doing James Beard research—Arianne Batterbury, founder of Food and Wine Magazine1—at the end of this lovely lunch where I was interviewing her, she said, "I think people have made far too much of James's sexuality. He never talked about it at dinner parties." Well, he wasn't going to talk about it at your dinner party.

I do consider it an indictment of food media generally that we haven't had that difficult conversation about Julia Child, that it hasn't seeped into the popular conversation about Julia. What I wanted to do with a Beard biography was to be able to present these disturbing, darker parts of this figure, who I believe, overall, is this admirable, inventive figure. Food media itself has been very, very conservative. I think outside of [Mario] Batali and MeToo, that there hasn't been a better discussion of difficult things.

Laura: When I came across that quote from a letter from Julia in your book, yes, I was shocked. I wasn't expecting it. Then I was surprised that somehow it never escaped [Laura Shapiro’s] book and made it into the wider press.

Is there anything really surprising that you discovered while you were doing your research?

John: I think understanding just a tiny bit more about Edna Lewis and realizing that in this world that she moved in in New York City in the 1930s and 1940s, that it was steeped in queerness. The level of influence that must've been on Edna Lewis from that world really did surprise me, having come to some conclusions as we all have about who Edna Lewis was through those later books.

Craig Claiborne just never ceased to disappoint me, but it also surprised me that his book, A Feast Made for Laughter, how any editor could have let him handle the revelation of not only of his spooning with daddy, but his very pronounced racism. Yes, he grew up in a Jim Crow society in particularly openly racist decades, but that nobody in 1981, his publisher could have said, "Hmm, let's contextualize this. You're telling these mammy stories and placing the black people you knew as a child in this certain way. Maybe we need to do this in a different way." That really surprised me. It also reinforced my idea that food publishing, cookbook publishing in America has been so conservative. I mean, was very conservative in the 20th century, shockingly so.

Then, I think the other thing that surprised me was really I had suspected that Alice B. Toklas had a much higher goal than just writing this cookbook for money, which was the myth that hovers around it—that she was this quirky, charming older lady who, 10 years after Gertrude died, just needed some money, and so she needed to write this book—but that she was aware of trying to create a piece of art in this writing, that it wasn't just a casual endeavor. Just very, very impressed really diving into that text; what a strange, strange book it is.

Laura: Early in this conversation, when you were talking about working in restaurants in the '80s and writing about it, you said that there was this disconnect between the queerness of the people working in the kitchens and the restaurants and what they were actually making. How do you feel about that now?

John: Well, the idea that chefs particularly express themselves, express their biographies in their food is something that we take for granted. In the fine-dining realm, we expect that. We want to see all of these childhood influences and even childhood experiences reflected on a plate. There's a chef, Dominique Crenn in San Francisco, a queer woman who grew up in France, and she was known in San Francisco at Atelier Crenn for orchestrating these menus around experiences of her youth growing up [in Brittany]. There was a course called “A Walk in the Woods,” and it was supposed to evoke this beautiful landscape of edible mosses and things trying to evoke this idea of being a girl and walking, getting lost in the forest.

I did this story that was published in 2015 called “Straight Up Passing” where I talked to contemporary chefs that I knew were out in San Francisco, but who had this complicated idea of being public. I completely respect their ideas for why that happened. In Dominique's case, she was the only woman chef in the United States who had a restaurant with a Michelin star, and even competing as a woman in that realm of fine dining was so difficult. At some point, I'm like, "You express everything about your past on a plate. What about your life as a queer woman, your romantic life, your aspirations, all that?" She's just, "Being where I am now is hard enough. Why would I want to make trouble, basically, by adding this other layer of complexity to an already complex identity in the kitchen?"

A few years later, Dominique was posting on Instagram photos of her wife, their family, so something definitely broke. It suddenly became like the stigma has cleared. I'm not saying that it doesn't still exist, but it's a completely different landscape. In early May, I went to the Big Queer Food Fest in Boston, which is this week-long festival. It's queer chefs from around the country coming and doing dinners and doing food tastings. I think that was certainly unimaginable in 2015.

In the case of that, we have Food Network to thank. Top Chef became a place where queer chefs had visibility and could talk about their queerness to this national, international audience. I think that's expanded the idea of what's possible for queer chefs and this queer culture of food. Last year I went to the first Queer Food Conference at Boston University, and so [there is] this embrace by academia of these ideas that there is this culture of queer food and how has it played out in the last 100 years, and what are the challenges, how things are changing now. We're in a very different landscape.

I guess I fear a little bit that that queer food could become just another shiny product, and that we'll just accept that as a product and not really look at the ambiguities of it, and not challenge ourselves in this notion of queerness, like what queerness means. Right now, in queer conversations, we're being challenged with notions of gender, which I think is amazing, and wonderful, and necessary. I mean, certainly, queer people of my generation, I know for some of them it's very challenging to think beyond these traditional ideas, this binary of gay/straight, men/women. I think we need to continue to explore how that plays out in food. I know Telly Justice, a [trans femme] chef at HAGS in New York City, even the food talks about creating these layers, like dishes that are layered, and then you open them up and taste the complexity, surprising in ways, going in different directions. I love that idea, not just claiming that you're queer, but really doing the work to see how you could express that in food.

Laura: When I saw something about the Queer Food Conference last year, I did a little research around it and realized that there were basically no academic books or trade books on queer food. I'm really glad that there is finally a conference, but it’s also crazy that it's taken so long. It’s interesting that your book is coming out now, and then there's another book on queer restaurants [Erik Piepenburg's Dining Out] coming out later this month as well. Why do you think that there's suddenly two books on queer food coming out at the same time?

John: Well, not to disparage publishing, but publishing is ready. They recognize, they see that there's a market. Book publishing is very speculative. They buy a proposal and then believe that two or three years later, there'll be a market for it. I think that's what's happening. I think that all of this percolating—Big Queer Food Fest, Top Chef—this has all percolated into the culture now to the extent where there is a readership, there is a market for this information. I'm so grateful for that.

I think telling these histories is long overdue. There was a book published maybe two years ago by Stephen Vider, called The Queerness of Home, where he looks at the history of queer domesticity and how that story had been overlooked because so much of queer history is about what's happening in the streets rather than how people are organizing their lives. I don't know if it was New York One, but during the first decade and a half of the AIDS crisis, in New York City, there was a program that would go into queer homes as a way of de-stigmatizing AIDs, like, "Yes, I'm living with HIV, and come into my apartment and meet my partner. We're raising a kid." Just that idea like New Yorkers would be taken into queer homes and find that they're quite ordinary, quite boring. That is a history that has only begun to be told, and food, of course, is a big part of that. It's here and it's coming. I think there'll be a lot more.

As Ever, Miriam

“It was in the archives that I fell in love with connecting the dots between people, places, and movements. I found my passion for reading between the lines, looking for coded or community specific language, and sharing those histories in accessible ways.”

Culinary Nostalgia and 'The Underground Gourmet Cookbook'

We all have those restaurants—those venues that, just thought of them, brings us back to a certain place and time in our lives. Maybe they are from childhood, possibly young adulthood; maybe they are still going, possibly long closed. Where you can be walking down a street half the world away and the sight of a chair through a café window can trigger a …

Ariane Batterberry, along with her husband Michael, also wrote a book on fashion history, Fashion: The Mirror of History (1982, originally published in the UK as Mirror Mirror: A Social History of Fashion in 1977).

Glad the book is out.

Johnny Nicholson and Karl Bissinger were lovers—but fyi they were emphatically not life partners.

Karl dropped Johnny, the day he took Johnny’s very sad looking portrait. Karl wanted monogamy and Johnny did not. Karl proudly spent decades with his life partner Dick Hanley, an artist who designed fabrics.

This is so informative! Can’t wait to read the book!