As Ever, Miriam

A Conversation with Faythe Levine on Archives, Letters, Love and Her New Book

“It was in the archives that I fell in love with connecting the dots between people, places, and movements. I found my passion for reading between the lines, looking for coded or community specific language, and sharing those histories in accessible ways.”

- Faythe Levine, As Ever, Miriam

Faythe Levine is an archivist, curator, writer, and documentarian—you might have seen or read her previous works Sign Painters (2013 - watch here) and Handmade Nation: The Rise of DIY Art, Craft, and Design (2009), both feature-length documentaries with accompanying books published by Princeton Architectural Press. We met over two decades ago in Milwaukee—she lived there and I, by a chance friendship, was visiting often to party—and have kept in touch, monitoring each other’s projects, aligned by our shared interest in archives. Currently, Faythe is the Hauser & Wirth Institute Archivist for the feminist art collective Women's Studio Workshop (established in 1974) in Rosendale, upstate NY; previously she lived off and on in Wisconsin for over 20 years.

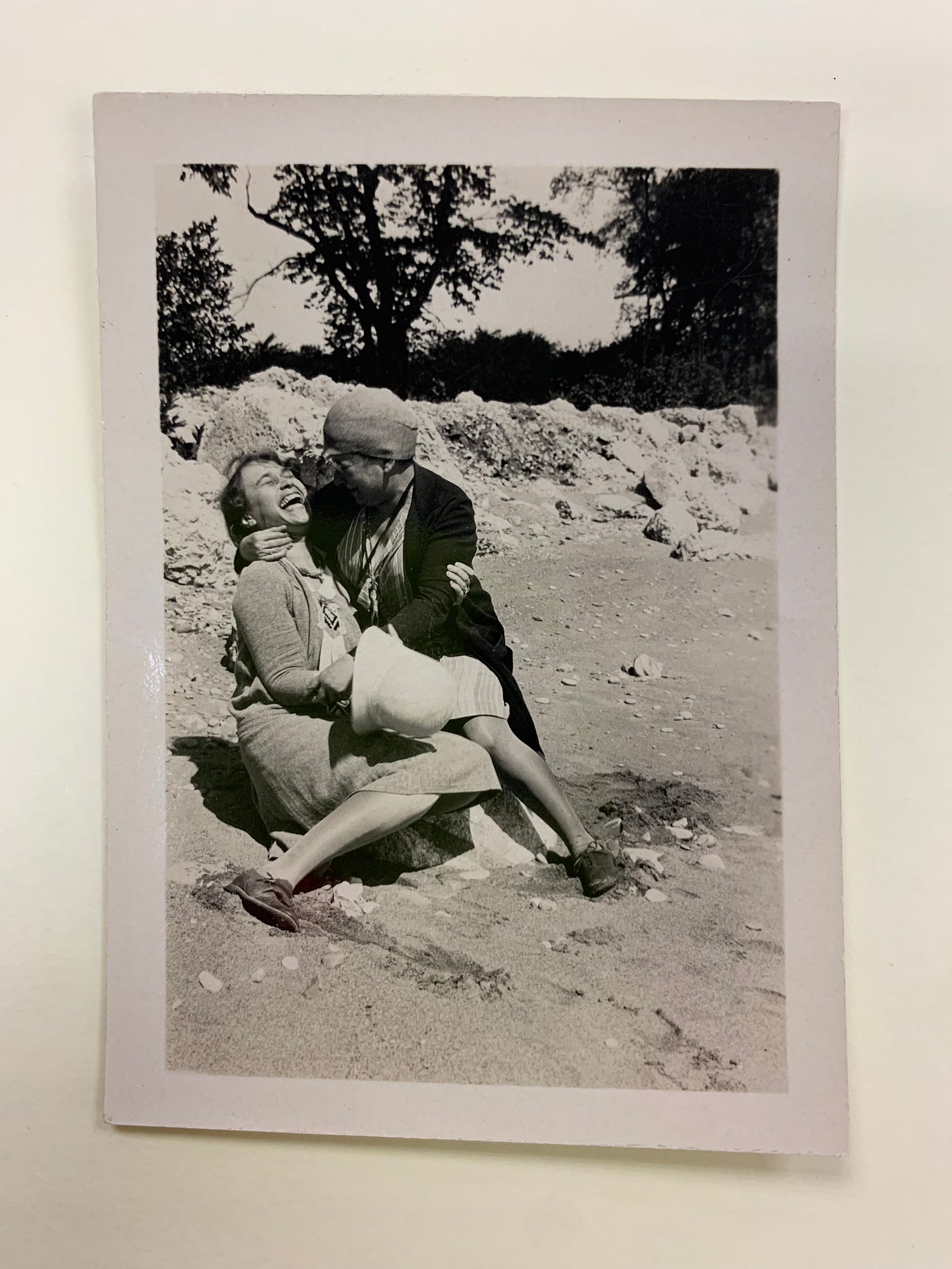

It is Wisconsin’s art history that provides the starting point for her latest book, As Ever, Miriam (OK Stamp Press, 2024). Charlotte Russell Partridge (1882-1975) and Miriam Frink (1892-1978) played an instrumental role in the development of Milwaukee’s art scene in the early-to-mid twentieth century through the Layton School of Art, which they founded and were co-directors of from 1920 until they were forced out in 1954. As teachers, artists, and administrators, they impacted generations of Wisconsin artists and architects, yet Charlotte and Miriam are largely forgotten. Faythe spent years sorting through their voluminous archive (housed at UW-Milwaukee Libraries’ Archives Department and owned by the Wisconsin Historical Society), trying to make sense of two lives completely intertwined, both professionally and personally—they lived together for 52 years (until Charlotte died in 1975) and built two homes together (check out the photos below!). Whether or not they were partnered romantically (though it seems very likely to me), Charlotte and Miriam lived their lives publicly together.

While As Ever, Miriam situates the couple within the local and national art scene they were part of (Charlotte directed the Wisconsin Federal Art Project and they both often traveled to New York and Washington for projects), Faythe focuses on the personal—pulling out Miriam’s signoffs in her letters to Charlotte, revealing a great depth of love and care across many decades.

A blurb from her publisher, OK Stamp Press:

Researched, transcribed, collected, and introduced by Faythe Levine, this book centers on the relationship and lives of Charlotte Russell Partridge (1882-1975) and Miriam Frink (1892-1978). Based on extensive archival and secondary research involving books, magazines, newspapers, and interviews, Levine brings readers into the work of connecting archival traces to tell stories about past lives. The book presents a collection of epistolary sign-offs from Frink’s letters to Partridge across the decades of their working and personal relationships. Levine takes time to provide extensive footnotes that bring context to these brief but rich archival excerpts. She includes reflections on quotidian details, vernacular translations, historical references, photographs, and information about the pair’s contributions to the arts and art education in Milwaukee, WI, and beyond in the early to mid-20th century.

I spoke with Faythe a few weeks ago about this project (six years in the making and still more to come), archives (historically and in the digital age), letter-writing, queer history, and more.

The first edition of 300 is nearly sold out—visit OK Stamp Press to request a copy. A second edition will be published by Combos Press this spring; to be put on a mailing list for book updates, you can email Faythe or follow her on Instagram. Also, subscribe to her Substack!

Laura McLaws Helms: How did you first learn about these two women, about Charlotte and Miriam?

Faythe Levine: I was working at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Wisconsin, which is an incredible museum that a lot of people don't know about unless they're in the world of artist-built environments, or sometimes self-taught art. I moved to Milwaukee in 2001 and then I left after 15 years, and I came back for this job at Kohler in 2017. I got hired there as a curator, and one of the first exhibitions I got assigned as an assistant curator was working with an artist whose name is Iris Häussler. [Iris] has alternate egos that she works under… she creates this fictional world and weaves in historical narratives. She had this loose framework that she was working with as her artist name that she was working under for this exhibition, and she was trying to link it to Wisconsin history.

I knew about the Layton School of Art in the back of my mind because if you live in Milwaukee long enough, people's grandparents went there. There are murals around the town. It gets brought up, but I never knew that much about it. I knew that there were women involved, but I didn't really know the whole story. I did a little quick deep dive into the history of the school, and I started asking more questions to a few local historians, and found out that it was founded by not only Charlotte Partridge, which is the person who gets credited for Layton most of the time—she was the more forward-facing of the two—but actually that it was Charlotte and Miriam who started the school together and then co-directed for 34 years until they were forced out of their position.

I spent some time in their papers doing research to lace the story of them into Iris's narrative of her exhibition, but it piqued my interest, and I had a lot of questions that weren't easily answered. It was really confusing to me that the school that had made such a deep impact on the Midwest and in Wisconsin, in particular… [that] there was just a lack of scholarship around the origin story around the women who started it, there were just a lot of blank spots and that's always a space where I like to step in doing my own research and I was curious about their relationship.

There were people who were confident that they were partnered, people who were confident that they weren't. I think initially, I really wanted to see if I could connect them to a larger queer network. That was the motivator initially, but it became much larger than that once I started spending significant personal time working with their papers.

Laura: When you started working on them, beyond tying them in with a larger queer network, did you have a plan for the research?

Faythe: Because I was on the clock at my day job, I was looking for these very specific signifiers of time and place to connect them to the exhibition. Since their papers are really expansive, I was just haphazardly going through stuff and photographing and trying to figure out some key pieces that we could get on loan to put in the museum for the exhibition. I think beyond that, once I had mental space to think about the expansiveness of what was there, in their papers, the personal correspondence and personal… the Milwaukee history and the Wisconsin history that was there—it just felt really apparent to me that there was a larger story to tell.

When I started going back on my own time, I was really curious if they had this lesbian circuit that was going to maybe crack open some Wisconsin underground lesbian history that wasn't really written about. There's some significant scholarship around queer history in Wisconsin and a lot of it is really focused on gay men and so I was very fascinated with the idea that there might be some other underground network or potentially they traveled a lot individually and as a couple and so I was trying to see if there was correspondence with any significant queer-identified people or women specifically in New York or Paris. That was the initial motivation, always on the back burner.

It just became apparent that there was a much larger story. The spaces that they touched were so expansive and the impact that they had, it just felt so, and still does feel so valuable to really look at the different networks and people that they were in communication with and impacted.

Laura: Given its expansive nature, at what point did you decide to focus on the personal letters, specifically the signoffs on Miriam’s letters?

Faythe: It took me a couple of years. I started working on this when I was still living in Wisconsin and I could just drive down to Milwaukee from Sheboygan, which is an hour north of Milwaukee on the lake. Once I moved, I had to be a little more strategic about my time than I had in the physical space, with their papers. I also was so overwhelmed by the amount of information that was there. They have their papers, and then they have some research files that are also as a part of their collection.

The researcher files were from when they were still alive, and they were working on their own story about the history of the Layton School of Art. They were working with a number of different hired researchers to try and tell their story. There are notes in old lady shaky handwriting from them in different pens. You can start to, if you spend time with the papers, figure out whose handwriting is whose. There's a lot of conflicting information coming from the same person.

Initially, I was thinking I was going to write a combined historical biography of both of them… [that was] going to talk about Milwaukee history and the art history of the area and the networks they were involved in. I'm not a historian and I got so overwhelmed with content and history and information and conflicting information that… I clocked that if I was going to do anything with the time that I had already invested in the project, that I was going to need to narrow my scope of research.

About two years in, I was still thinking about the potential of lesbian networks or larger queer networks and connections, and I was like, if I focus on their personal correspondence in particular, at least I have a space where maybe I might find something specific. I focused, I started to go through the correspondence, which was archived in chronological order, but everything was mixed in with business and personal.

Initially, I was going in and I was photographing all the correspondence, but it was just the mass amount of correspondence that was saved. Even that was a lifetime of work without any research assistance and just the amount of time it takes to transcribe someone's script. From there, I was like, okay, I'm going to take it in a notch closer and just look at their personal correspondence. Then it became, and this is a spoiler alert if someone hasn't read the book, but it was a surprise, but the correspondence was very one-sided that was archived.

It is predominantly Miriam's letters to Charlotte that were saved in their papers. Charlotte passed away 10 years before Miriam, and her papers went to the Historical Society first. There is a note in the finding aid that said that Miriam wanted her person that she was working with, her researcher, to destroy a lot of her papers. I think a lot of her correspondence was destroyed or not donated to the Historical Society for whatever reason.

Looking at their personal correspondence, I started to photograph the letters that were between the two of them. With the content of those letters, because they were partnered for so long, the combination of looking at when they first met in school and started writing letters, and then reading the letters as they progressed—5 years when they started the school, 10 years when they were like deep in this establishing this successful but haphazard school. Just watching the progression of the playfulness go into this workspace. Also, domestic correspondence about like, “Don't forget to clean the fridge out before you go to Chicago.” Then the amount of information about travel logistics. It was really interesting to me to think about the trajectory of a relationship over the course of these markers of their lives.

A book of just transcribed letters was a thought, but that also was just so much information because they were doing so much because they were living together and working together running this art school. I think there could be value in that as a document, but I thought as an artist and as a creative person, and as like a romantic letter writer still, I really like correspondence and mail writing.

I was thinking about how and looking for, again, these potential signifiers of intimacy and devotion. I started to look at how Miriam was saying goodbye to Charlotte in these letters… the last two or three sentences, would always summarize like, “Don't forget this. Make sure you sleep. Take care of yourself. I love you.” It was this wrap-up of a potential, two to three-page rambling thing of travel logistics or other stuff.

It felt like a special conceptual space to land at looking at how one says goodbye over the course of 50 years of a professional and personal relationship. Once I landed on that, it became really clear that was a comfortable space to narrow it down to a bite-size document that I could then still situate them historically with an introduction—add significant amount of footnotes because there was still so much information I was interested in—but potentially use it as a gateway into their incredible lives to hopefully lure some people in and not create this tome of history that also was out of my league.

I think it's important to say, at least for me, that I do have a long relationship with correspondence and letter writing. I think there was definitely some reflection on my own ways of staying in touch with people and my own relationships to letter writing and sending mail. I landed on that decision in deep pandemic when I had started a romance with someone… We were writing letters in a way that I hadn't since I was in my early 20s, because it was pandemic and I had time to make fancy cute mail and send packages. That definitely had an influence now that I'm thinking about it.

Laura: It was remarkable how, from just the three sentences at the end of each letter, how much you get to know Miriam, particularly. You get a feel for how she was as a person, especially interacting with Charlotte. I don't think anyone could read it and not think that this was a romantic relationship.

Faythe: I'm still close to the material—I still haven't had the opportunity to really talk about them extensively. I appreciate that you said that you do get a really good understanding of Miriam's personality.

I think what's really special is that people who have any concept of who Charlotte and Miriam were, don't understand Miriam. She was really keeping it together. She was the one behind the scenes doing a lot of that unseen labor. I don't even mean in a domestic sense, by any means—I think they definitely had domestic help, they were businesswomen—but she was Charlotte's editor, she was writing a lot of the speeches or she was really reeling Charlotte in, in a way.

She was creating a home for Charlotte to take care of her, for her to be able to go out in the world and be this forward-facing person. I think that it’s really exciting for me to give Miriam a little bit of time to shine, even though neither of them have really gotten their moment, a contemporary moment to shine. I do think regardless of how they identify themselves, there's no space in my mind that they weren't deeply partnered. In a sense of, in every way, their lives were so deeply intertwined, both in a domestic sense and in a workspace.

For anyone who's ever worked with someone that they've been dating or partnered with, it's incredible to me the amount of overlap that they had in their lives. It makes me wonder what was actually going on, but we'll never know. It just seemed like the amount of love there, and it was a two-way street, definitely a two-way street, was very apparent and really special, and the way that their friends talk about them and the way that people who were welcomed into their home and the community that they nurtured. They were a powerhouse couple. It's really incredible to look at the scope of all the work they did.

Laura: It's interesting because you just said that it was definitely two-sided and yet, when you read just Miriam’s letters, it can feel a little one-sided. I was wondering if there was any evidence—I know her letters aren't there—but evidence that it was balanced?

Faythe: I think there's the evidence of the way that people spoke about them… I think where it became evident was in the correspondence from family, from friends, from holiday cards that they were receiving, people always asked about the other one.

People always talked about them as a pair: “Give my love to Charlotte,” “Give my love to Miriam.” If the letter was to one of them, they always mentioned the other one. “Thanks for having us over for the party. It was really lovely.” “Thanks for opening your home.” There's all of this really clear information from the outside and through the papers, through other correspondents.

I think that even with their families—I was really fascinated. They spent holidays together… and their mothers wrote them all individually. The sisters wrote each other's. They were just fully in each other's lives in every way.

There are a few handfuls of letters that I did find from Charlotte to Miriam. There was, I don't know, under a dozen… There's one chunk and I think it was almost they were missed when maybe they were donated and accidentally put into the archive, but they were from a trip to Germany… they had a lot of inside jokes that I feel I'm probably missing some full understanding, but you can tell there was a playfulness between the two of them.

Yes, I feel confident it was a two-way street. Whether or not Charlotte appreciated the amount of work that Miriam was doing for her, that I'm unclear of. Miriam was keeping it together for them as far as the couple goes, that feels clear to me. I don't think Charlotte would have been going to the doctor as much. It feels obvious that she was the one who was spreading herself thin and Miriam was constantly trying to reel her in or keep her safer, rested.

Laura: Why do you think there's been so little scholarship on them and the Layton School and the various things they've worked on?

Faythe: I think at the core, Wisconsin, it's a flyover state. Chicago gets the beam of light if people are talking about the Midwest. I think there's a lack of scholarship just due to location.

The fact that they're women feels really obvious to me. I think that the drama around how they were pushed out of their position got a lot of press. The way that the school ended up closing in 1974, it had a sad ending—the financial crumbling of the school itself.

Charlotte and Miriam started in the basement of an art gallery and then they did a capital campaign to build this fantastically modern building that was on the lake that won all these like architectural awards and ended up having to be demolished because the city was going to build a freeway along the lakefront. The school ended up moving a little bit more inland, what's now more of the suburbs. That was the turning point of the school having this demise. It wasn't in the city center anymore. It wasn't in a beautiful building.

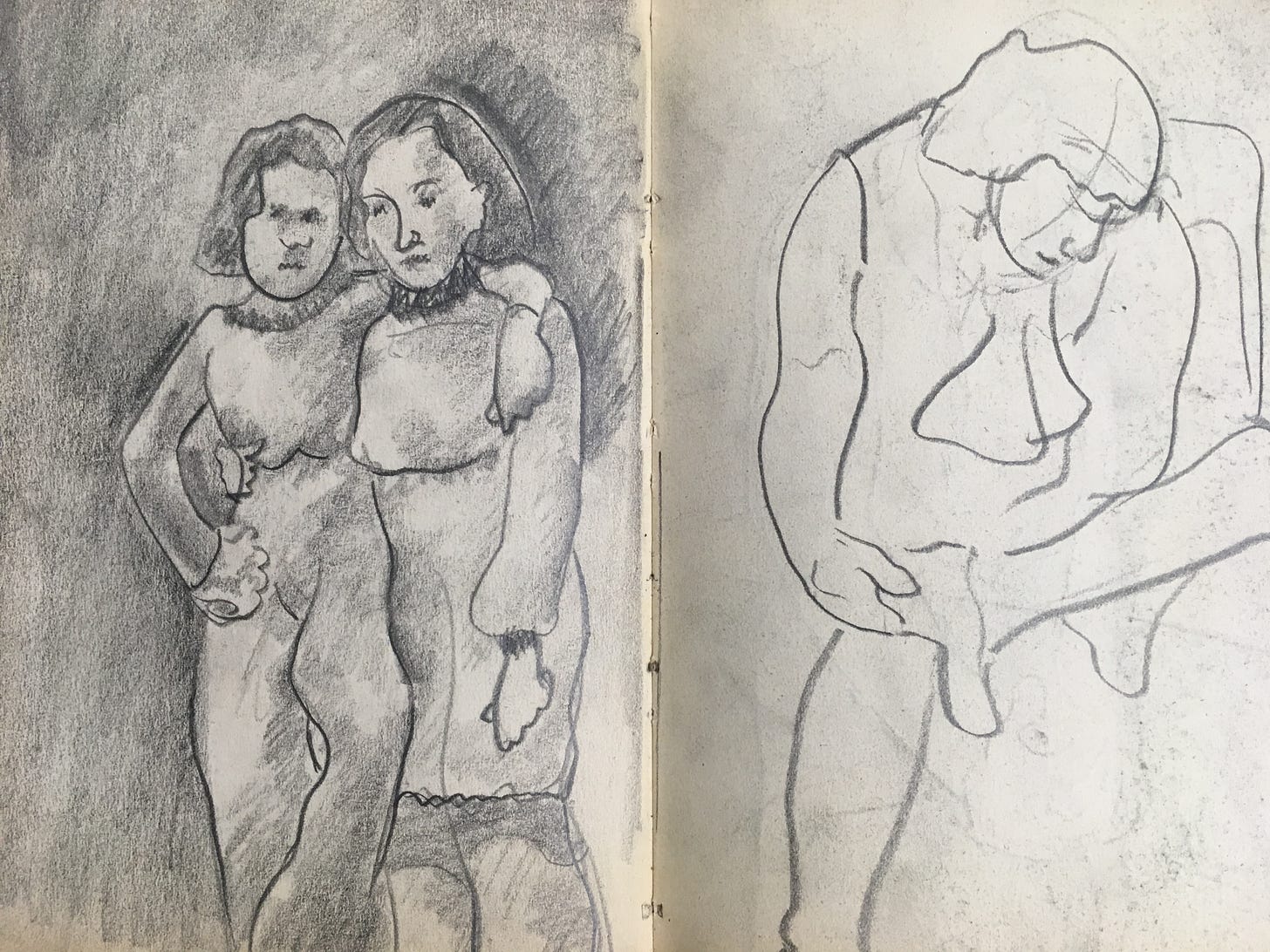

Sometimes I'm always surprised at the things that people don't pay attention to. I think people know about the Layton School of Art. I think they were just overlooked. Administrators don't get a lot of shine. I think Charlotte had an art practice. She always continued to sketch. Her passion was architecture and she was a painter. She taught composition at the school. They had very few teachers at the beginning and she was one of them. I think that administrators… [are] not that exciting.

I think that the scope of their lives, if and when there is more scholarship done around them, I think… that people will be like, yes, why didn't we know about this? There's already been some interesting turns of events. The Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design (MIAD), which is this art school in Milwaukee that was founded by two Layton School of Art graduates. Now MIAD is claiming Charlotte and Miriam as a part of their founding history, which I find a little bit convoluted. I think the fact that people are grabbing at straws for some DEI, queer history—there is an interest in them as this potential having this queer legacy story, which I think as long as it's accurate is great.

I think there's just so much room for different entry points of scholarship around their lives and the work that they did. I think that it will happen. I think that there's renewed interest in the work that they did, just as people become more aware of their surroundings. I do think there's this interesting shift in people having more of an interest around place and history and how things got to where they were. I always hope that.

Laura: There were so many little things that I kept being like, "Oh, I'd love to know more about…” Like, Miriam was teaching literature for art students. I thought, "Well, what is literature for art students? What was considered literature for art students?” And I wanted to learn more about the house that they designed and built. Those kinds of things.

Faythe: Their house is amazing. It's still standing. There's so many little sub-stories. They had a number of houses together. I'm super interested in their shared domestic space. They had a cottage that Charlotte designed. Her sketches are all in their papers. There's all these photographs of her up on the scaffolding with the guys building the house. She was very tiny. She was 4'11'' so super short, and Miriam was very tall. They had this also really sweet height difference that people loved to focus on. In the pictures of her on the scaffolding, she's just doing her own thing. This is in 1929, 1930. Then they built this very contemporary modern home that is still standing. The cottage is no longer there. All of these homes that they lived in together were featured in the newspaper. They were in the women's section.

There's this incredible article after they retired, about their home and their art collection and how they live together in the space. It was like “friends, Charlotte and Miriam,” just all this very coded language about their relationship, but they were very public in their partnership and in Milwaukee. I think people just rolled with it… For whatever, again, sure, maybe they were just best friends. Regardless of how they were perceived, it is really impressive to see the ways that they were portrayed in the media during their lifetime. They had shared bank accounts and all the things, all the signifiers.

Their contemporary, mid-century home was incredibly stunning. They worked with a husband and wife architecture team, Willis and Lillian Leenhouts. The wife was a graduate of the Layton School of Art. She went on to work with Charlotte. After Charlotte retired from Layton School of Art, she had her civic duty that she was really invested in doing affordable, well-designed living for single elderly people, which to me also really clocks as a queer-coded space. They designed this tower that was, at the time, called the Zonta Manor, but has been renamed. It's also still standing.

The Leenhouts are very well known in the Wisconsin area for designing lots of mid-century architecture. Their daughter, whose name is Robin Leenhouts, I've become friends with and went to her house and we were able to talk about—she has memories of meeting Charlotte and being in the backseat of the car and Charlotte chain-smoking in the front of the car and her mom.

It's still kind of close, but there's that generation of people who may have met her when they were very young, who are now very elderly in their 80s. It feels like a really important time with their history to lift them back up into the contemporary conversation.

Laura: Amazing. Knowing nothing about the school or really anything about Wisconsin art, even just your introduction and the timeline helped give me a grounding in the area's history.

Faythe: A lot of the graduates from the Layton School of Art went on to have very prolific, very significant careers outside of the Midwest. There’s a lot of people who went through their program who made these significant cultural impacts on the East Coast, on the West Coast [among those artists are Richard Lippold, Edmund Lewandowski, Karl Priebe, Margaret Davis Clark, and Lois Ehlert].1 Their ripple effect, if you think about the Midwest… going outward was very palatable.

I started doing this mind map situation where I was trying to map everything as a potential exhibition idea. That also got really overwhelming because of the extent of their networks and Charlotte's work with the WPA as the director of the Wisconsin WPA. She had all these Washington connections and it's just really expansive [other members of their network included Boris Lovet-Lorski, Francis Toor, and Frank Lloyd Wright].2 They were amazing women that were so ahead of their time. It's really inspiring. They feel like kindred spirits and that's been a really important part of my investment in telling their story because I'm excited for other people to know of them and to recognize them as important parts of our history.

Laura: As an archivist and as a person who's really into letter writing yourself—obviously, this is all based on letters—how do you feel about future of archives, now that so much of our communication is on phones? It's DMs and texts.

Faythe: I think about it all the time because my day job is working as an archivist in an organization that has been around for 50 years. There's a really clear point in the papers here where things go from written correspondence to printed out emails, which I think is a really interesting moment for those of us who lived through the transition of the internet becoming a part of our daily lives. I have a handful of printed out emails from my early 20s where I was like, "This is a letter. I have to print it out." It's really funny to look at them.

I think that, from a personal perspective, I've kept all of my personal correspondence. Because I spent so much time reading other people's mail, I really started to think differently about what do I want people-- Do I want people to read my personal letters that were written to me? I don't have copies of my letters I wrote people. I have mixed feelings about it.

I can't speak to our society as a whole. I think the loss of information is probably noticeable, but we have so much more information available to us. I don't know if the scales even out. I don't know what the scales are, but I don't know if there's an evening out of content. We rely on correspondence historically to tell us so much about what was going on outside of newspaper articles or a very specific part of society that were saving certain things. I feel like the internet saves such a larger vast amount of information from a larger spectrum of people. In some ways, it's not the same. It doesn't have that tactile [element]. We can't go to a place and open a folder and experience someone's personality through their script or look at the postmark or the postage.

It's confusing to me what to do with the quantity of information that exists now on the internet. I guess the personality I feel is lost. There's a sense of certain aspects, I think, that are lost without having the physical material. Again, we have access to so much more information that's potentially going to be accessible. Who knows if there's some global collapse of the internet then we lose a lot of information.

"What do we save? What's it for? Who do we want to see it?" These are big questions when you're thinking about legacy or your own personal legacy for family, for heirlooms. I think there's just so many different things to unpack when thinking about the stuff we hold dear to ourselves. As a researcher, some of the stuff that's the most interesting is the little notes and scraps that somehow made it along with the letters and the things that were intentionally saved. I think for me, the list of birds that Charlotte and Miriam saw in their yard that somehow was kept in a folder that I've found is one of my favorite things that really makes them human and humanizes them. These are the birds that they saw from their living room window and they took the time to write them out and somehow that was saved and that feels really special.

Laura: I always think about this question when I'm in an archive because I am so into all of the papers and the little things. When I was doing my Thea Porter book, something like an unpaid gas bill at a time when that there were some financial problems—those kinds of things add much more to the story, to your understanding of what was going on. Or just like a little scrap of paper with a recipe or something.

I just wonder if there was this researcher in the future looking at artists or these same kind of people that I look at today, that I look at in the past, what will they be seeing? How will they be able to construct our lives? Will they be looking at archived Instagrams or something? Which is different than a letter because it's about what you're putting out to the world.

Faythe: It's curated. It's a curated space. I think a lot of people are having these conversations and I think they're really important conversations to have especially within community archive spaces that are outside of academia. What are we choosing to save from our communities and thinking about future knowledge sharing and information sharing. I think there's a really cool intentionality that can happen around it. I think that that's happening in some capacity. In times of, to name climate crisis as a thing that we're all facing and looking at, by having the option of having things stored on a cloud, we are able to also have that as this safe space for now. We don't know in perpetuity what will happen technologically.

Thinking about those different scraps, still it's a curated space. I will say knowing that Miriam made the request for a lot of her papers to be not included in her archive by her researcher—I don't know who made those decisions, but it was still a curated choice.

The bulk of their papers, which are combined as a collection, were from Charlotte. A lot of it has content from Miriam in there. That was donated when they were both alive but it was considered Charlotte's donation. Then Miriam made a second donation later. She made a request that the majority of her papers were destroyed and not donated. That's why Charlotte's letters, if she would have saved them, I'm assuming they were destroyed or not donated. Charlotte was very much a part of what papers went to the Historical Society, which I will say, is not the case for every archive and made me feel less intrusive about spending so much time with their personal letters because I was like, "This was consensually donated to a historical society so I don't feel like I'm overstepping some boundaries of unpacking someone's personal information," which isn't always the case. Sometimes papers end up in places for different reasons.

I have a theory that Charlotte was maybe a little bit more transparent around their relationship. This is rooted-in-nothing, but just feeling like I know their personalities. Miriam's letters were fairly formal. There was a lot of care and a lot of adoration, but there was never anything explicit beyond talking about domestic duties in their letters, and a general sense of care.

In my mind, I'm like, "Maybe Charlotte was more loose-lipped about certain aspects of their relationship and that was part of why Miriam didn't either save those letters or ask for them to be destroyed." That's rooted in just speculation, just to be very clear. We'll never know.

Laura: Has working on this book informed your work at the Women's Studio Workshop or is your work at the Women's Studio Workshop informed in any way by this research?

Faythe: Oh, that's a good question. I feel like my personal work and my day work has always had some blurry lines between—I feel really lucky that I've had the opportunity to always pretty consistently have day jobs that also reflect my interest. Working for a feminist arts organization feels like an extension of the legacy of Charlotte and Miriam. My job is very administrative. It's a lot of spreadsheets. I think about the unseen labor of a lot of archivists so I guess there's some malleability between those things.

I think just in general, as the way that I exist in the world, having the opportunity to lift stories out of archives and out of spaces or out of things that I've discovered or found is something I feel really passionate about. Getting to do that at my day job, at Women's Studio Workshop, I think the things that I unearth here while I'm processing papers, might be the stories that I'm trying to tell or share are probably different than someone else who might just be processing the papers and doing the job as the archivist.

I'm consistently interested in the both/and. I'm excited to get people excited about things or to plant a seed that might get someone to understand that they could do something similar or tell a story about something that they're excited about. I think that's really something that fuels my work as a researcher in general.

I think Charlotte and Miriam have deeply impacted the way that I will do that work moving forward. At some point, I'd like to move away from their story but I still get sucked in and I'm very much haunted by them. It's exciting. There are some students that Charlotte and Miriam had that I'm pretty obsessed with that I wish I could shift my energy into, but I'm not there yet. There's only so much time in the day.

Laura: Earlier, you mentioned the possibility of some exhibitions. What might be happening?

Faythe: I have an exhibition slotted at a very small house gallery. Lynden Sculpture Garden is a place in Milwaukee, and they have a gallery that was the original house of the family at the sculpture garden. I'll be doing an exhibition there in the fall of 2025 rooted in the research around Charlotte and Miriam. The scope of the exhibition is not fully ironed out yet.

Like I said, I'm really interested in their domestic space. I want to do more than show pictures of the interior—I want to somehow unpack it a little bit further. I'm really interested in having people understand the scope of Charlotte and Miriam's reach and the networks I keep talking about. A way to visually do that feels important. Like I said, it's a small space. We might do some 3D renderings of the artist's cottage that no longer stands.

I do know that there is some work being done by some other researchers now—some people who are focused on the Milwaukee architecture scene, and there's some work being done around the Layton School of Art, specifically, in connection to this architecture project. I also know the Leenhouts, the architecture team that I mentioned, are having an exhibition around their lives at some point in Wisconsin.

That’s why I feel like there's a forward momentum with their names maybe being just more accurately presented. They were just always portrayed in this very specific way up until this moment that wasn't enough. I think I'm just hoping moving forward, that they'll be framed with a little bit more acknowledgment and a little more equal acknowledgment for the two of them when people speak about Layton School of Art and the impact it had.

The thing that was really incredible about their schools, they created a space that they did night classes so people who had day jobs could go to school for art at night if they wanted to become an art teacher or just do art classes. They had weekend classes for children that were free for 20 years. Then they started to have to charge a little bit. They were really creating this accessible space that was also just really radical in what they were doing in the classrooms like teaching literature, having co-ed live drawing classes. People were flipping out because there were nude people and there was a co-ed space. It's pretty incredible that they just were like, "This is how we want to do this. We want to have this school and we want to do it this way." They just made it happen. That, to me, is really powerful.

From Faythe:

Richard Lippold: took classes as a youth at LSA then became an industrial design instructor years later. He remained in contact with CP & MF and they had a piece of his work in their collection.

Edmund Lewandowski: LSA graduate with a long art career, who later replaced CP + MF as the director of the school (this was very drama fueled).

Karl Priebe: LSA student (I’m a huge fan of his surrealist paintings)

Margaret Davis Clark: LSA alumni, succeeded Charlotte in her FAP (Federal Arts Project) project director, which became the Wisconsin WPA Art Program (sponsored by the state) in 1939-1942 and later was at the University of Redlands CA (50 years), 26 of them teaching elementary teacher candidates.

Lois Ehlert: Children’s book author/illustrator who was a LSA student in advertising design

More from Faythe:

Boris Lovet-Lorski: Was early LSA faculty and remained friends with CP + MF when he moved to NY. They talk about spending time with him in the city and visiting his studios.

Francis Toor: Hosted CP + MF in Mexico and they remained in contact for many years. C + M would help promote her work and tours in Mexico with their networks. Fun fact is Diego Rivera wrote her obit.

Frank Lloyd Wright: CP put together a very controversial exhibition before Wright was known for his work. The exhibition at the Layton Gallery (same building as the school), curated by CP in 1930, was two years before the Museum of Modern Art, NYC, show: “Modern Architecture: International Exhibition.” Olgivanna Lloyd Wright (3rd wife) came at the end of the MKE exhibition and stayed at CP+ MF apartment. He also got along well with MF, and they both talked about his time there in many interviews.

Oh I love this!