The Mame Collection

Leo Narducci, Theadora Van Runkle and Movie-Fashion Tie-Ins

The symbiotic relationship between film and fashion is always an intriguing one to study—how fashion influences movie costume and the opposite, and then the use of these shared inspirations to market both the clothes and the movies. My very first newsletter was about the fashion-movie collaboration of Oscar de la Renta and The Madwoman of Chaillot, and below is a look at some marketing tie-ins surrounding Mame.

Just after I finished putting in the final footnote, I received a text that Angela Lansbury—who I talk about below—passed away. A legend who will be dearly missed.

This post is too long for email so click on the title to read in your browser or Substack app—it’s worth it even just for the images!

"Life is a banquet and most poor sons of bitches are starving to death."

Few characters are better dressed than Patrick Dennis’ Auntie Mame. Across book and play and film and musical and musical film, Mame’s eccentric lifestyle and fashion sense have long captivated. Set in New York and taking place over the Great Depression and World War II, Mame’s wardrobe proves a bounty for costume designers—covering the years from 1928 to 1946, and the most eccentric and unique take on high fashions. The original Broadway adaptation of the novel, Auntie Mame, ran from October 31, 1956, to June 28, 1958, with Rosalind Russell in the role of Mame and her gowns by Travis Banton. Russell again took on the role for the movie version, released December 1958—her costumes by Orry-Kelly. When the story was later adapted into a musical, Mame, Angela Lansbury introduced the role; her costumes by Robert Mackintosh (better known at the time as the designer for Seventh Avenue juniors line Musette). Mame ran on Broadway for 1,508 performances over four years (first with Lansbury and then with Janis Paige) to near ecstatic reviews—Lansbury, Bea Arthur and Frankie Michaels all winning Tony Awards for their roles. The musical went on to tour the country (with Celeste Holm in the lead role) and be produced on the West End (with Ginger Rogers as Mame).

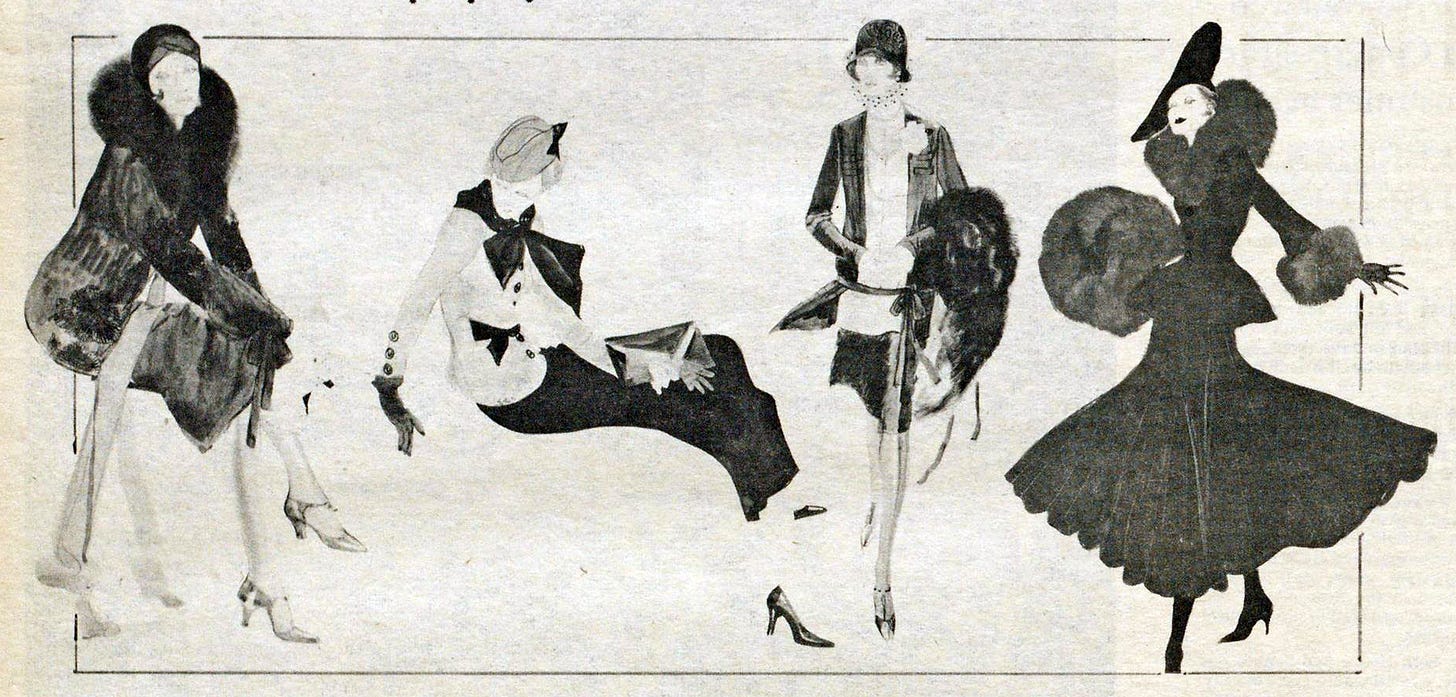

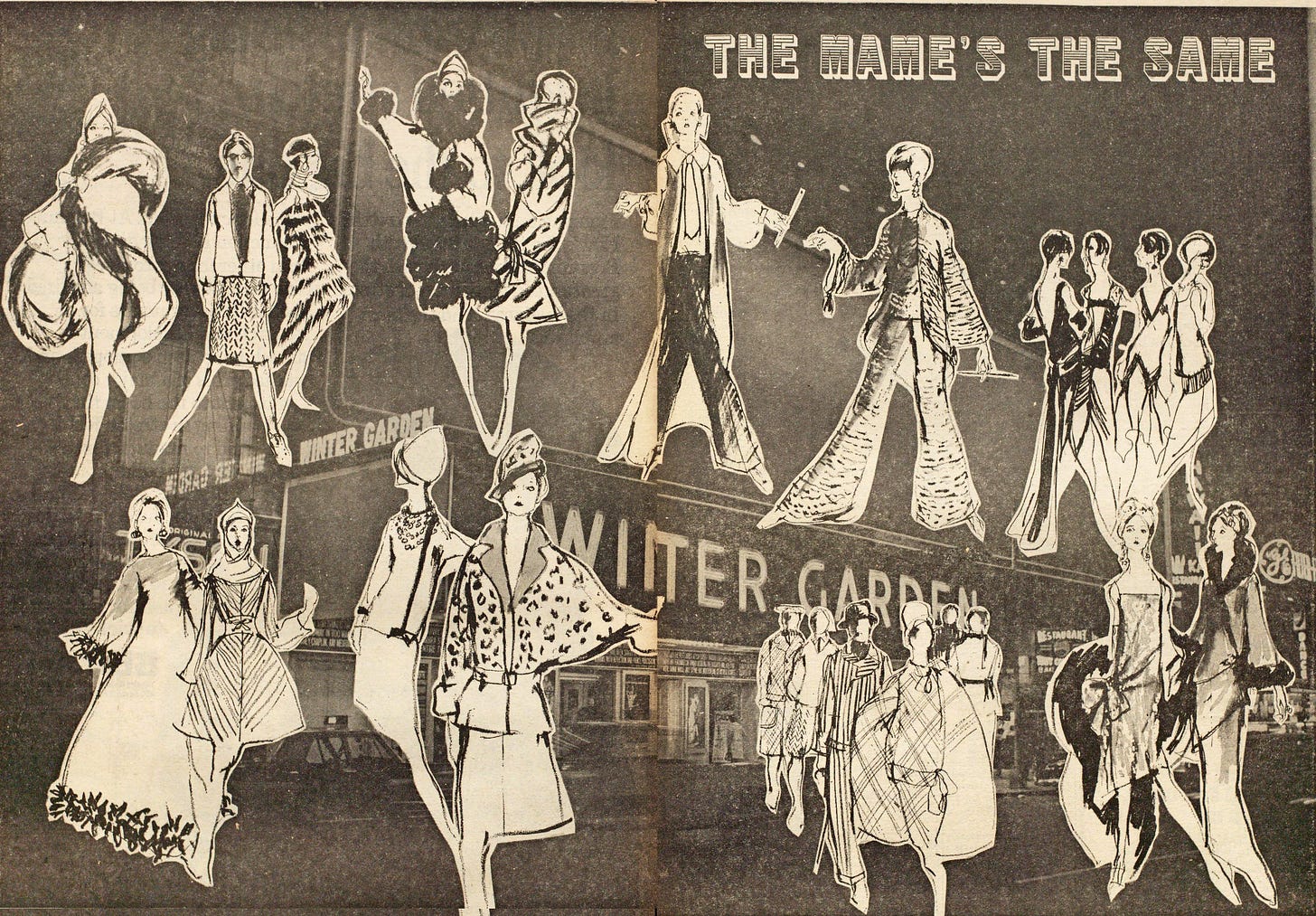

Suffice to say, by the early 1970s Mame’s style was well-known to anyone with a passing interest in literature, film, and theatre—and had played a large part in mini-revivals in those earlier eras’ fashions. Mame’s Broadway run fed into the late 1960s regurgitation of 1930s fashions; most often connected with movies like 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde, that revival can also be traced to Mackintosh’s OTT costumes. Prior to the musical’s premiere, Women’s Wear Daily interviewed him on his approach to the iconic character and period costuming. For Mackintosh, historical accuracy was not of prime importance; “I didn’t want to be ‘accurately period,’ especially when we get to the Depression scenes… costumes more like the Hollywood Thirties when they’d watch Crawford wear 90 dresses in a single film, know they couldn’t really have them but could dream.”1 Angela had thirty costume changes, including eight in the first scene alone—Rosalind Russell had only seventeen in the original play. Under Mackintosh’s direction, textile designer Julian Tomchin created some specially printed chiffons and plaids, Emme designed over a dozen custom hats, and Jacques Kaplan created a suite of extraordinary furs: “Mame goes from a zebra coat to a leopard suit to Mongolian wolf to red fox to suede to monkey fur to white broadtail to sable… everything to build that luxurious look before she loses everything in the Depression.”2 That blending of the past and present—unbeholden to historical accuracy, instead updating an evocation—proved irresistible to fashion designers and manufacturers. Within months, WWD was describing “the Auntie Mame look” as one of the key trends of 1967.

Throughout 1971 the possibility of a Mame movie adaptation cropped up in gossip columns. Mame’s writers wanted Lansbury to continue in the role she had so excelled in, but since 1966 Lucille Ball had been carrying on a behind-the-scenes campaign for the movie role. At the time the 60-year-old star was filming her third network sitcom, Here's Lucy, and her overall star power won her the role (much to Lansbury’s consternation). Though Ball had yet to be announced as the lead, when she broke her leg in a skiing accident in early January 1972 it pushed the start of shooting back a year. Theadora Van Runkle was brought in to design the costumes—as the Academy Award-nominated costume designer for Bonnie and Clyde (her first film), Van Runkle was an ideal choice. Similarly to Mackintosh, Van Runkle had approached Bonnie and Clyde as less of a period piece and more of a collaboration between decades; star Faye Dunaway said of the Van Runkle’s costumes, “The clothes are divine…She took what’s hip now in the ‘60s…combined it with the ‘30s…they’re masculine styles, but in a feminine way.”3 Bonnie’s midi skirts and soft sweaters had almost instantly filtered into the Seventh Avenue collections, from Chester Weinberg to Sarmi to the mass market.

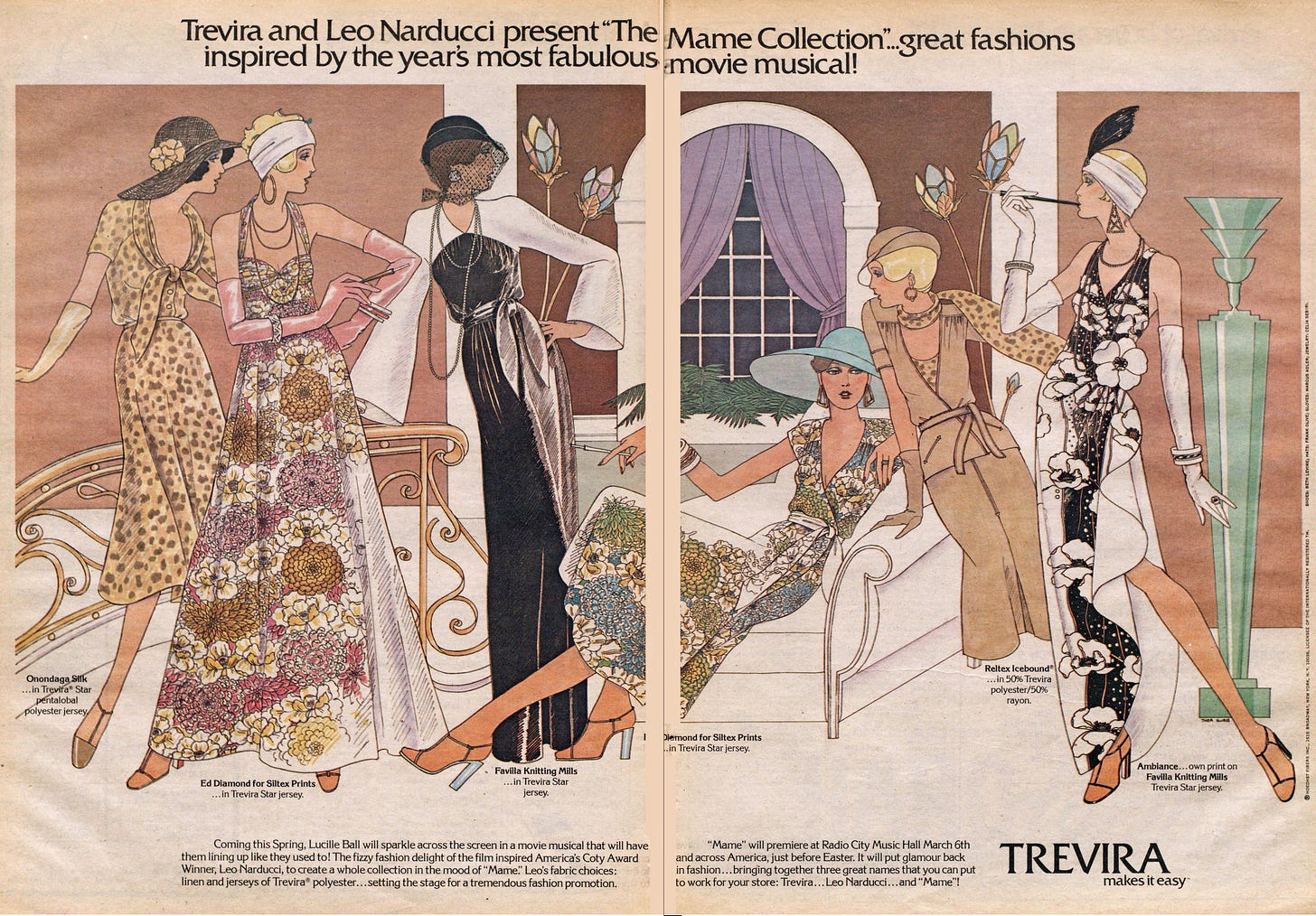

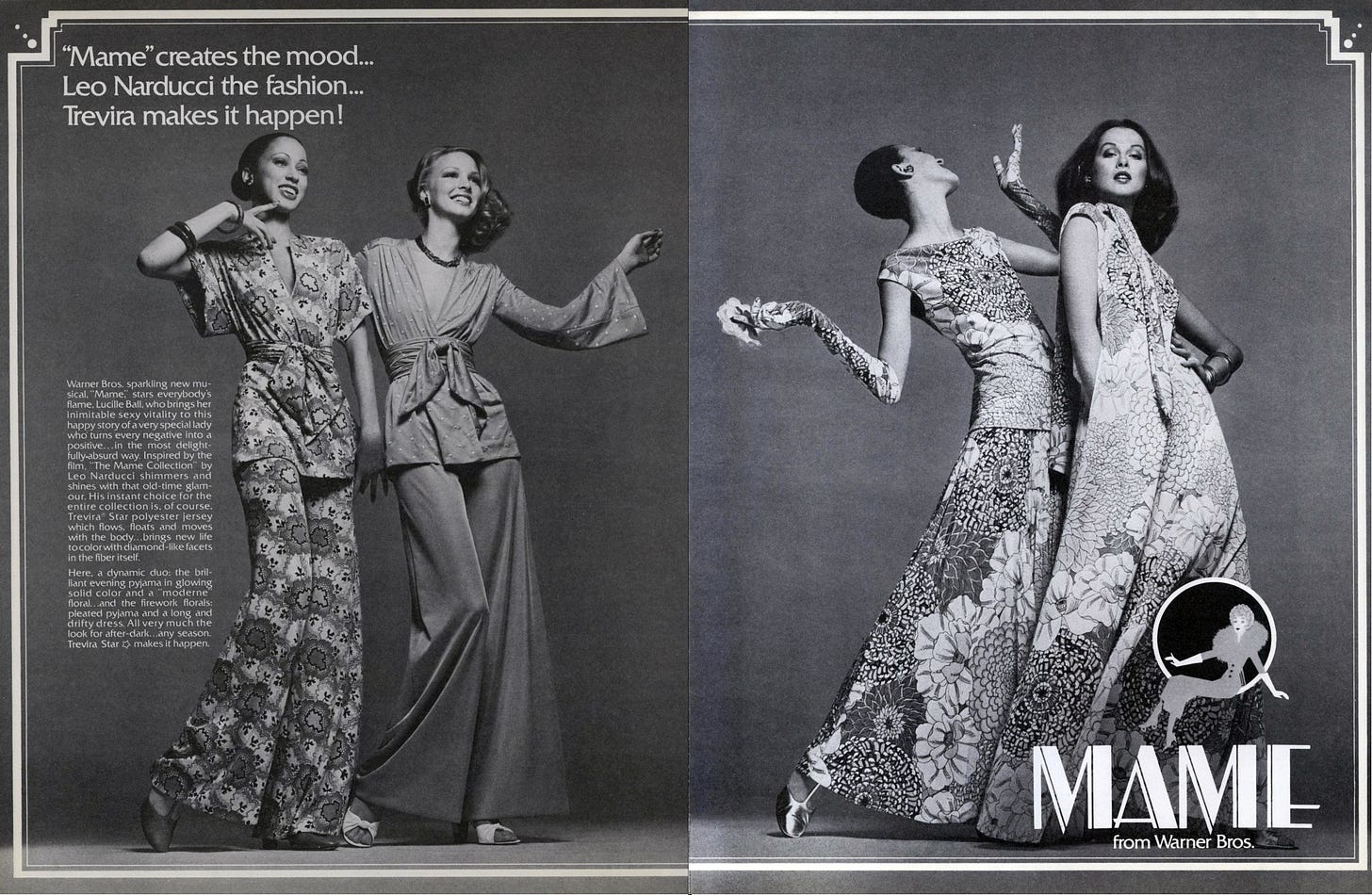

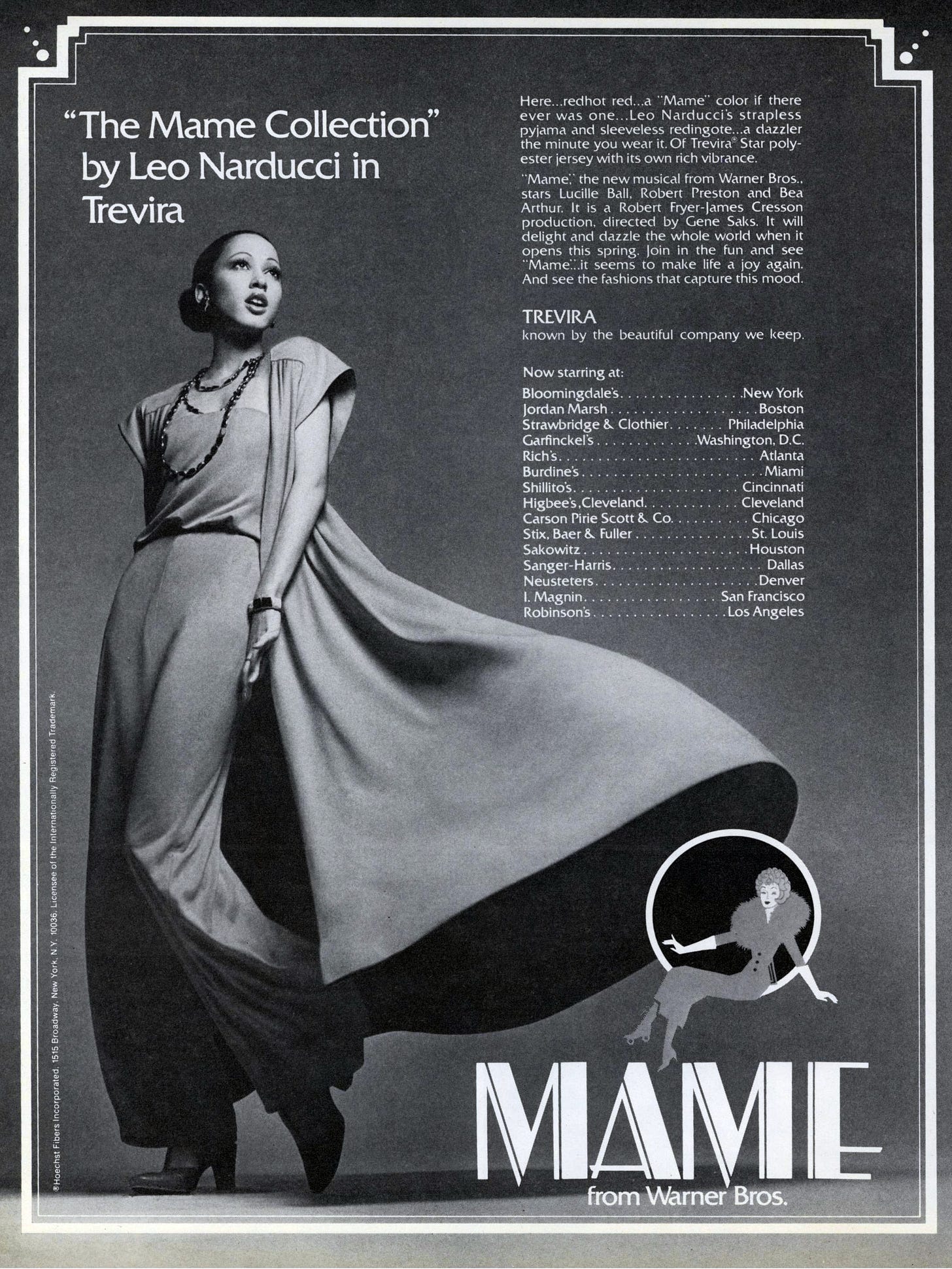

The very thought of Theadora bringing her artful touch and a $150,000 costume budget to Mame was enough to have designers racing to their sketchbooks. Among them was Leo Narducci, a successful fashion designer who had previously won the prestigious Coty Award in 1965 and whose primarily eveningwear company had done $5 million in volume in 1973. As a fan of both the play and the musical, he decided to base his spring-summer 1974 collection on Mame, prior to the release of the film. “I feel like the kind of clothes are very timely—the whole glamor thing. I’m not doing anything directly from the costumes. It’s just the mood I sort of got into—the ‘0s and ‘40s pleats and drapey things.”4 Focusing on slinky evening clothes—dresses and pajamas—Narducci collaborated with Trevira, a polyester fiber company, to produce the line. It was the first time that Trevira had commissioned a designer collection showcasing their fiber.

For Narducci, his designs were translations of Auntie Mame’s irrepressible joie de vivre into clothing: “Mame represents the mysterious fascination that is the essence of woman’s nature…. All I did was pick up the Mame mood which is simultaneously slinky and sexy.”5 Having not seen the film, Narducci was filtering his memories of the book, play, and musical through his own design language. In a way this was similar to how Van Runkle approached her costume designs—she had never seen the musical and purposely avoided looking at photos of it and earlier iterations, instead translating her reading of the book into clothing form.

“I just decided from reading the book that Mame has to be the most urbane, worldly creature, privy to everything that’s happening in New York and Paris. She runs around with Picasso and Stein. She creates life. She gives the feeling that life is worth living—that’s the best feeling in the world you can give anybody.” – Theodora Van Runkle6

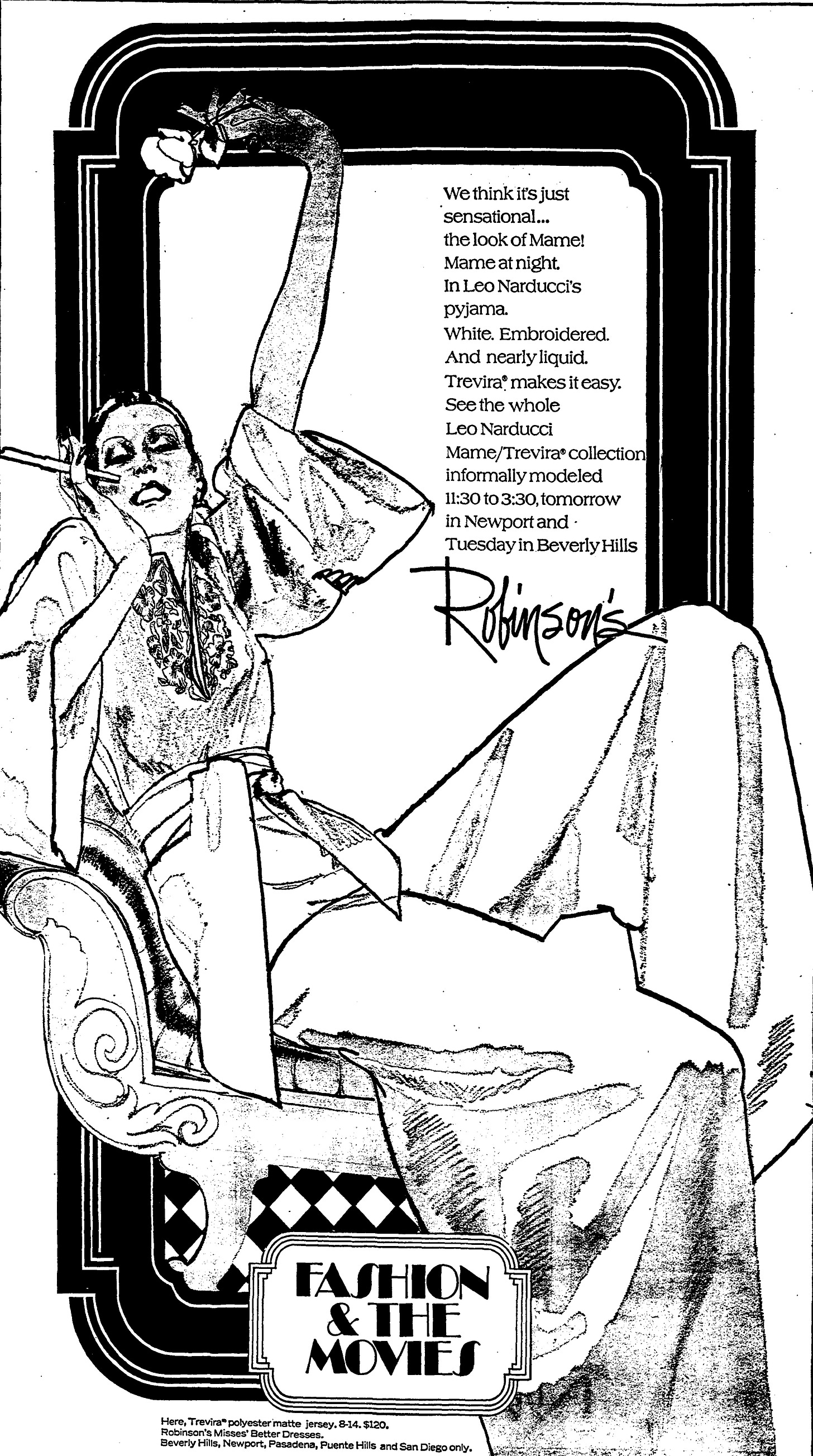

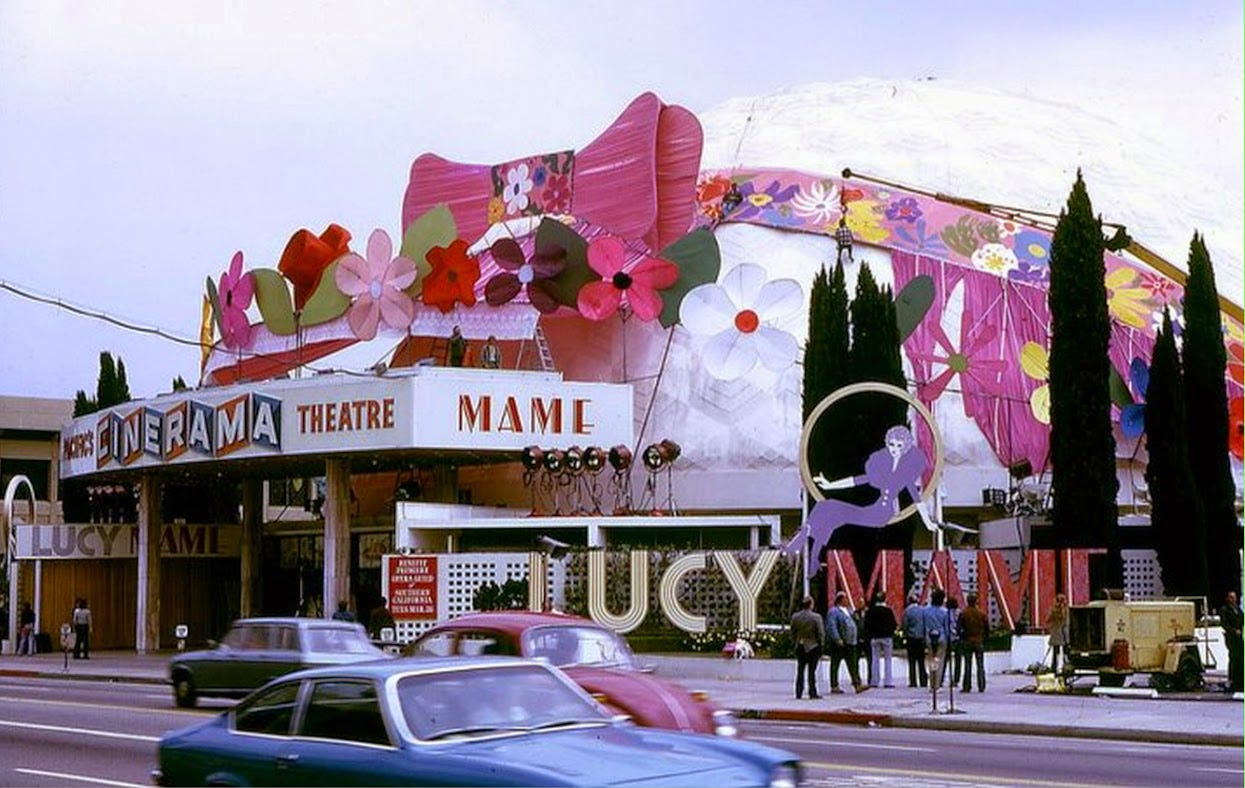

On January 15, 1974, “SA’s best models—dancing, whirling to film clips and slides in a smashing presentation of Leo Narducci’s summer clothes” at a champagne reception at the Plaza Hotel, which received high marks from the department store buyers in the audience.7 With Mame set to open in cinemas nationwide that March, a similar tour was contracted for Narducci to visit cities where both the movie was showing and his clothes were for sale. In each, he presented his collection at department stores or charity galas, bringing the women of small cities across America into his fantasy evocation of Mame. In Kansas City, Missouri, the Women’s Auxiliary of Research Hospital & Medical Center organized “Soiree ‘74” in conjunction with Stix, Baer & Fuller (the local department store chain); the event featured a fashion show of Narducci’s designs modeled by “Kansas Citians prominent in society, the professions and sports.”8 The Kiwi Club’s (a social and charitable organization for former and current flight attendants from American Airlines and several connected airlines) 11th biennial national convention opened at the Beverly Hills Hotel with “An Afternoon With Mame” that included a fashion show of Narducci’s designs and costumes from the film. Models danced and sang along with songs from Mame during a fashion show at Boston’s Jordan Marsh. Though Narducci had designed this collection prior to watching the movie, all these events were produced in collaboration with Warner Bros. who supplied clips from the film. At the Fashion Group’s luncheon in Beverly Hills, a clip was shown on screen followed on the runway by the costume from the clip and then a similarly styled Narducci look; this procedure was followed throughout the whole fashion show.

“Every woman should be a little bit happier catching a glimpse of herself as Mame, because the Mame mood captures a totally feminine feeling of yesterday, of today and of tomorrow.” – Leo Narducci9

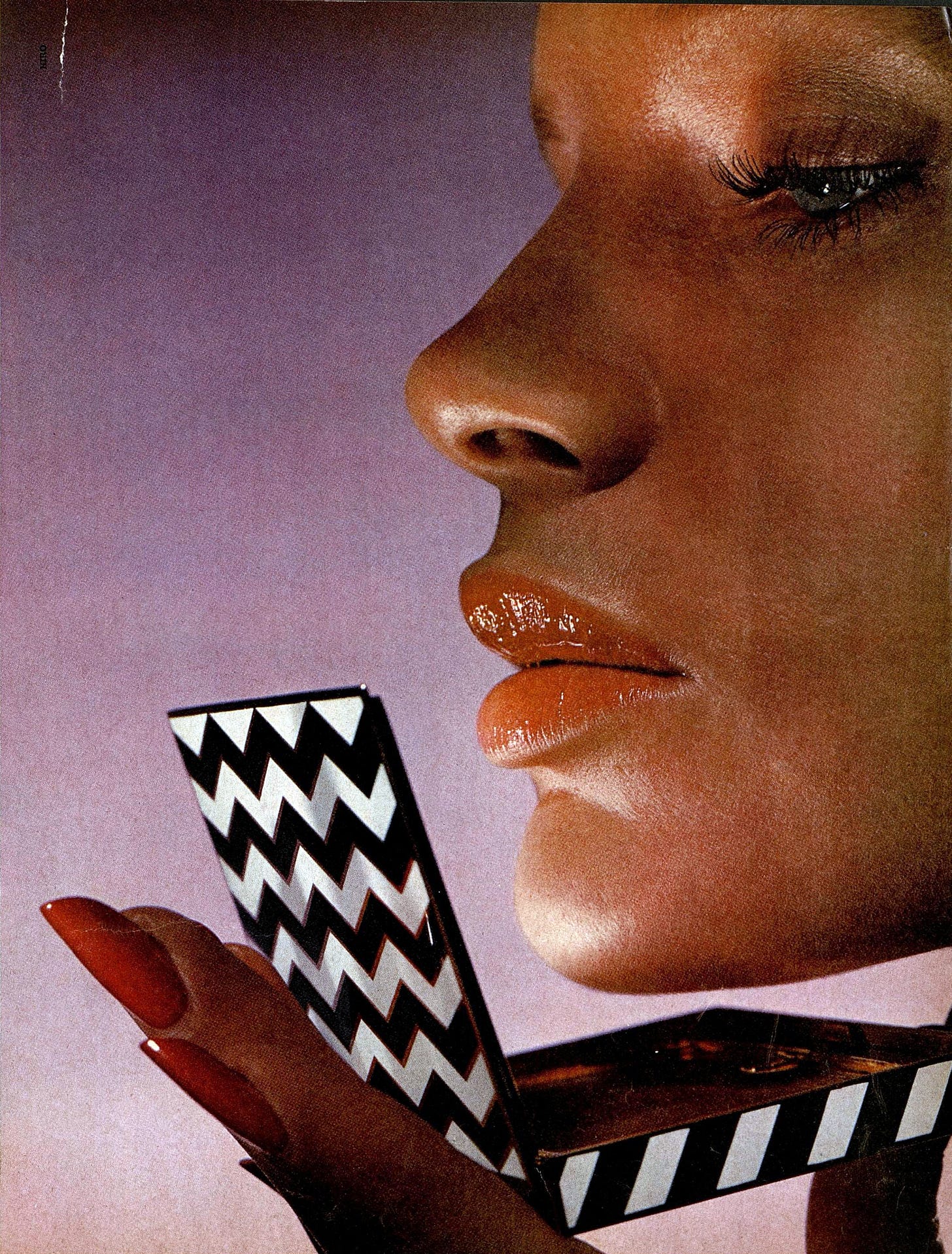

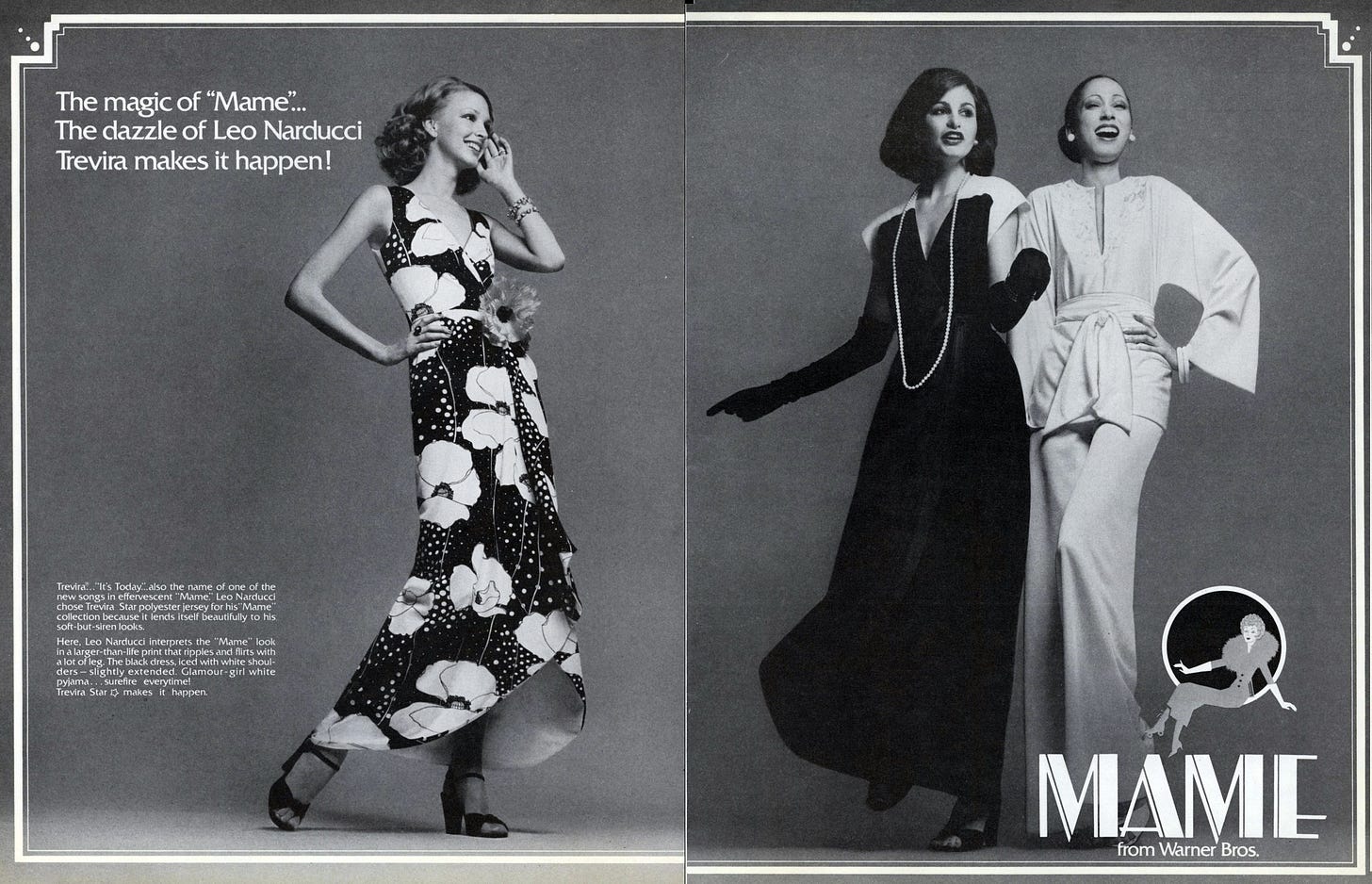

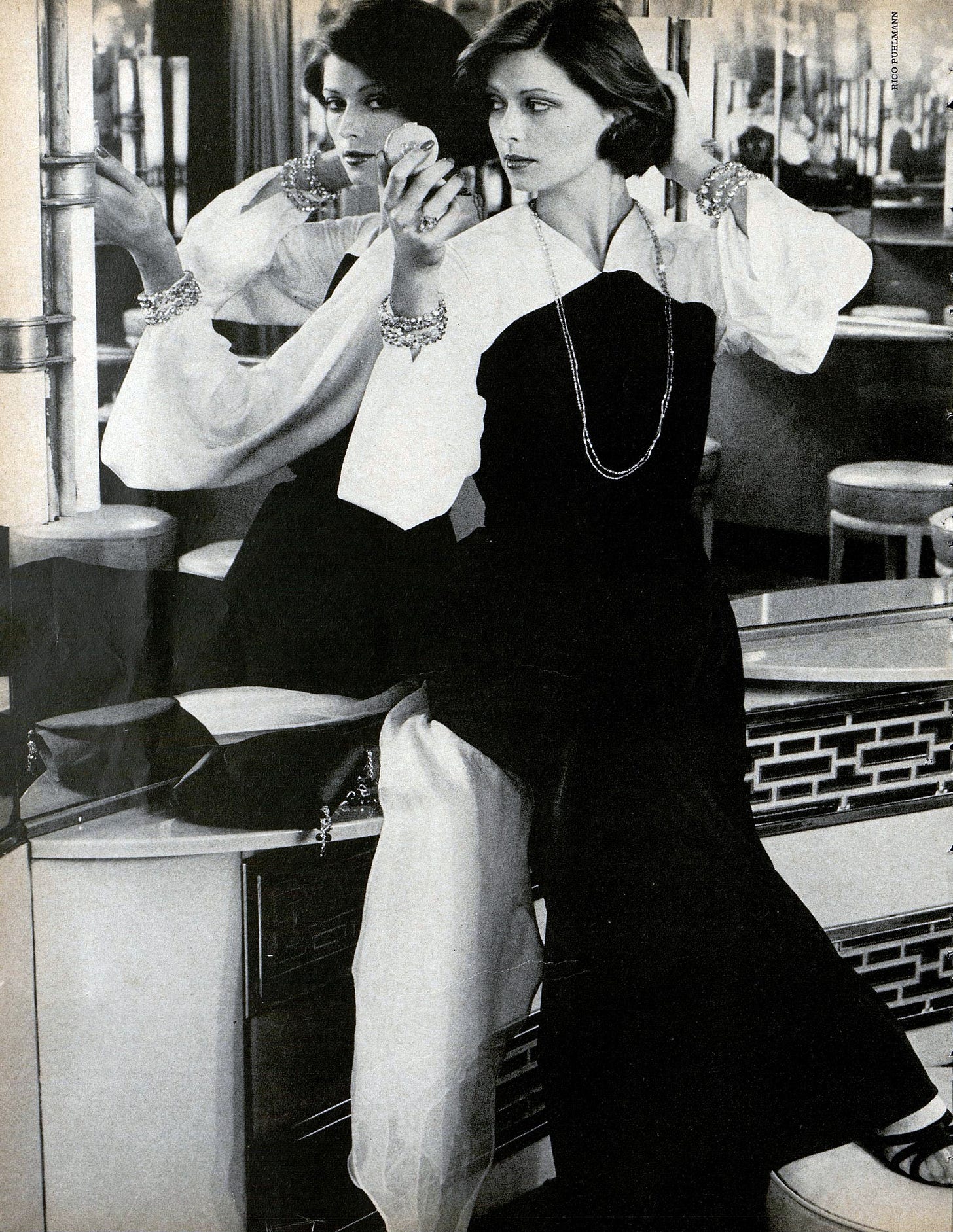

As for Narducci’s designs, they were described as evoking “a contemporary feeling” while still capturing “the joyous independence that is synonymous with the original Mame character. Vibrant colors set the tone for the collection, reflecting the colorful personality of Mame.”10 Slinky Trevira jerseys cut into pajamas of wraparound tops and palazzo pants or long floaty dresses. Julian Tomchin returned to design some custom prints including an oversized poppy one that was fashioned into a wrap-over dress with a high slit and cascading ruffle. Textile designer Ed Diamond created an all-over flower print that made its way onto wrap-dresses and bare halters. A camel short-sleeve skirt with animal-print camisole and scarf echoed 1930s daywear, while a black and white color-block gown replicated Old Hollywood silhouettes. A six-page advertorial for the collection was published in the April 1974 issue of Vogue featuring models of the moment Pat Cleveland, Karen Bjornson and Apollonia van Ravenstein (scroll to bottom), while Harper's Bazaar published a spread of Regine Jaffry looking strikingly beautiful in two of Narducci's designs. While no sales numbers for the collection were printed in the media, it’s likely that it was a success—the combination of highly publicized, more easily priced (all items under $175 and most between $70-100, which translates to around $420-600 today), non-wrinkle easy-to-care-for fabrics, and attractive cuts boding well for sales.

Similar to Revlon’s extravaganza color promotions (written about here and here), the makeup brand Dorothy Gray came out with the “Flaming Mame” collection of lipsticks and nail glosses in shades of Flaming Red, Flaming Coral and Flaming Pink. Using this collection, makeup consultant Robert LaCourte designed total face and hair looks based on those created for the film by Van Runkle, Ball makeup artist Hal King and her hair stylist Irma Kusely. As part of her huge promotional tour, Ball flew from city to city aboard a United Airlines 727 converted into a flying Mame set—and smart marketing teams made sure that every city she visited had Narducci and Gray promotions at the top department stores.

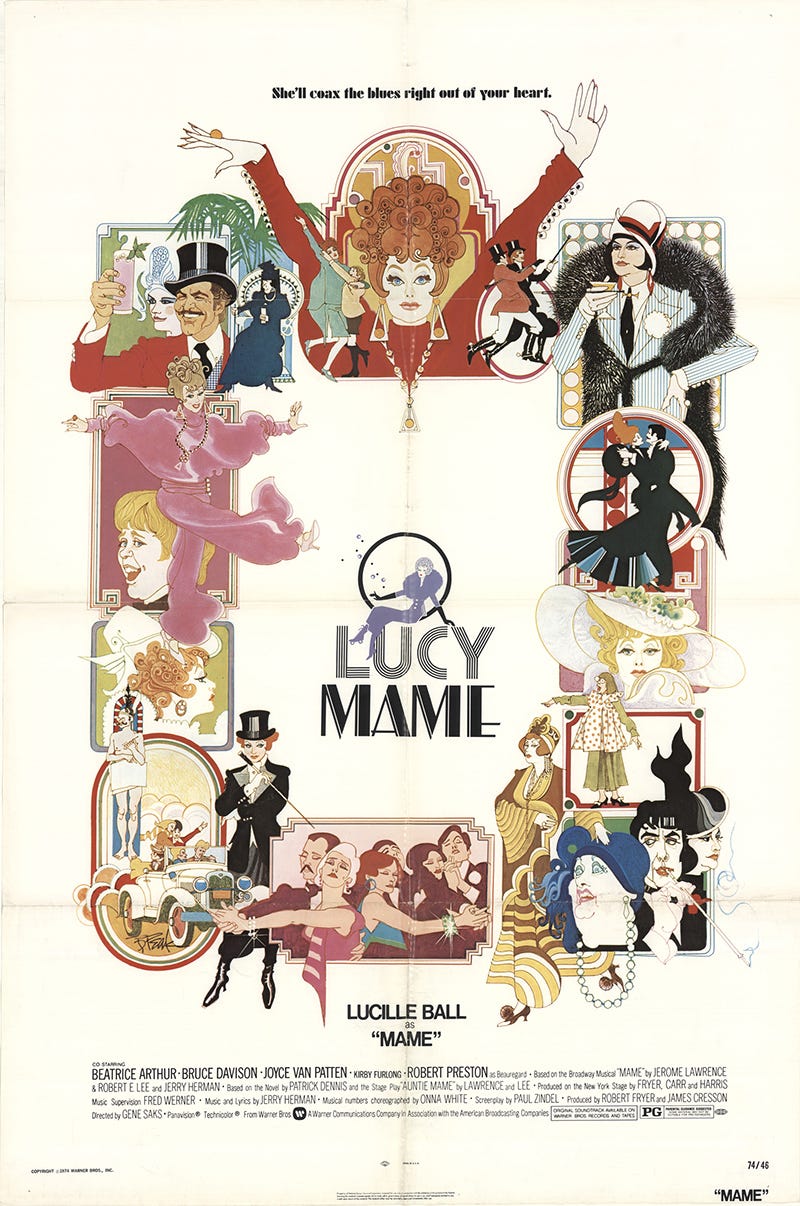

Mame opened Easter weekend at Radio City Musical Hall but was a box-office and critical failure with Lucille Ball universally declared to be miscast and too old for the role. With Ball a self-confessed poor singer and dancer, she is badly out of place in a role that calls for singing, dancing, and a very sprightly demeanor. While Lansbury would have made for a much finer movie Mame, if you haven’t seen it and you enjoy the truly camp, it is worth a watch—don’t go into it expecting as good a film as Auntie Mame nor as good a portrayal of the character as Rosalind Russell, and simply enjoy Lucy being the grande dame she had worked so tirelessly to become. Van Runkle costumes for Ball are beautiful, though movement-constricting and perhaps suited better for mannequins than the perpetually in-motion Mame. I will say that her costumes for Bea Arthur are an absolute travesty—the assumption made by many is that Lucille refused to have any female co-stars outshine her and forced a more matronly look on Arthur.

Lucille Ball’s Van Runkle-outfitted Mame is a diva through and through, excessive in costuming and acting. By taking as his inspiration the idea of what the film costumes could be, Narducci’s designs smartly took on a more subtle (and much more sellable) approach to the “Auntie Mame look.”

“To me the real heart of this movie is that growing older isn’t the crime that we make it. Mame is courageous and elegant and she goes out and meets life.” – Theodora Van Runkle11

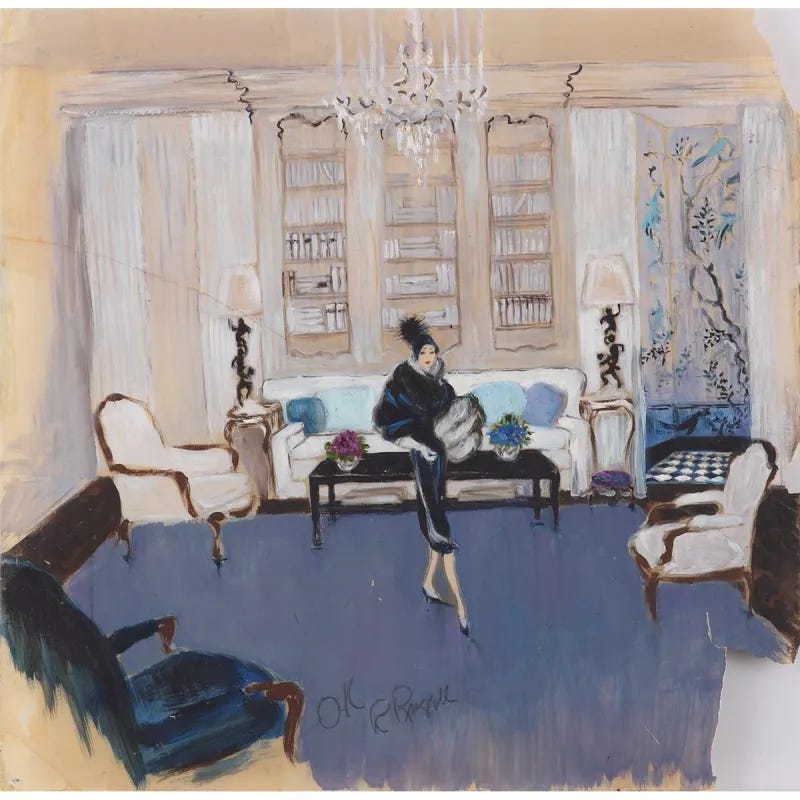

“Trevira presents ‘The Mame Collection’ by Leo Narducci - ‘Mame’ from Warner Bros.” advertorial, Vogue, April 1974.

Bob Peak’s masterful poster for Mame, 1974.

“The Mame’s the Same,” Women’s Wear Daily, March 9, 1966, 4.

Ibid.

Jody Jacobs, “There’s Something…”, Women’s Wear Daily, April 19, 1967, SII35.

“Eye,” Women’s Wear Daily, January 4, 1974, 6.

Marian Christy, “Narducci’s leap of joy,” Boston Globe, December 28, 1973, 36.

Beth Ann Krier, “Thea in the Big Budget World of ‘Mame,’” Los Angeles Times, January 12, 1973, F1.

“Eye,” Women’s Wear Daily, January 17, 1974, 11.

“’Mame’ Fashion Show Set For Cancer Benefit in KC,” Boxoffice, March 25, 1974, 22.

Adele Leonard, “Fashions by Adele: Designing by Mame,” Jewish Exponent, April 19, 1974, 28.

Ibid.

Phyllis Feldkamp, “Movie Modes,” Christian Science Monitor, March 25, 1974, 14.