“Oscar de La Renta’s Own Chaillot Look"

La Belle Époque, Oscar de la Renta and Fashion-Film Tie-ins

Welcome! Thank you for joining me here—some newsletters will be longer historical deep-dives like this one, sometimes interviews, as well as a mix of other formats. I hope that you find these newsletters interesting, valuable and enjoyable.

A few months ago I came across this interview with Oscar de la Renta—posted in February by The Bobbie Wygant Archive channel on YouTube, this short interview still hovers at around 150 views almost a year later yet opened up a deep rabbithole of research for me. Renowned news reporter Bobbie Wygant began her career in television in 1948; now 95, she has worked for NBC 5 for over 70 years—a truly legendary career.

In this clip dated (incorrectly) from 1970, a crop-topped and beehived Bobbie leads by asking de la Renta how he came to pair up with Warner Bros.-Seven Arts (W7) on his upcoming “Chaillot” collection. The safari-suit-clad Oscar answers by stating that it was a natural connection due to the turn-of-the-century look of his collection. What caught my attention was that I had never seen any mention of any cinematic tie-in’s in any book or exhibition on de la Renta—in the late sixties de la Renta designed some costumes for theater but, through the whole of his career, never for the cinema. Over the years I’ve written quite extensively about fashion-TV tie-in’s, particularly the licensing deals surrounding the 1980s prime-time soap Dynasty—with this interview clearly alluding to a fashion-movie business deal, I knew I needed to look a little more closely into it.

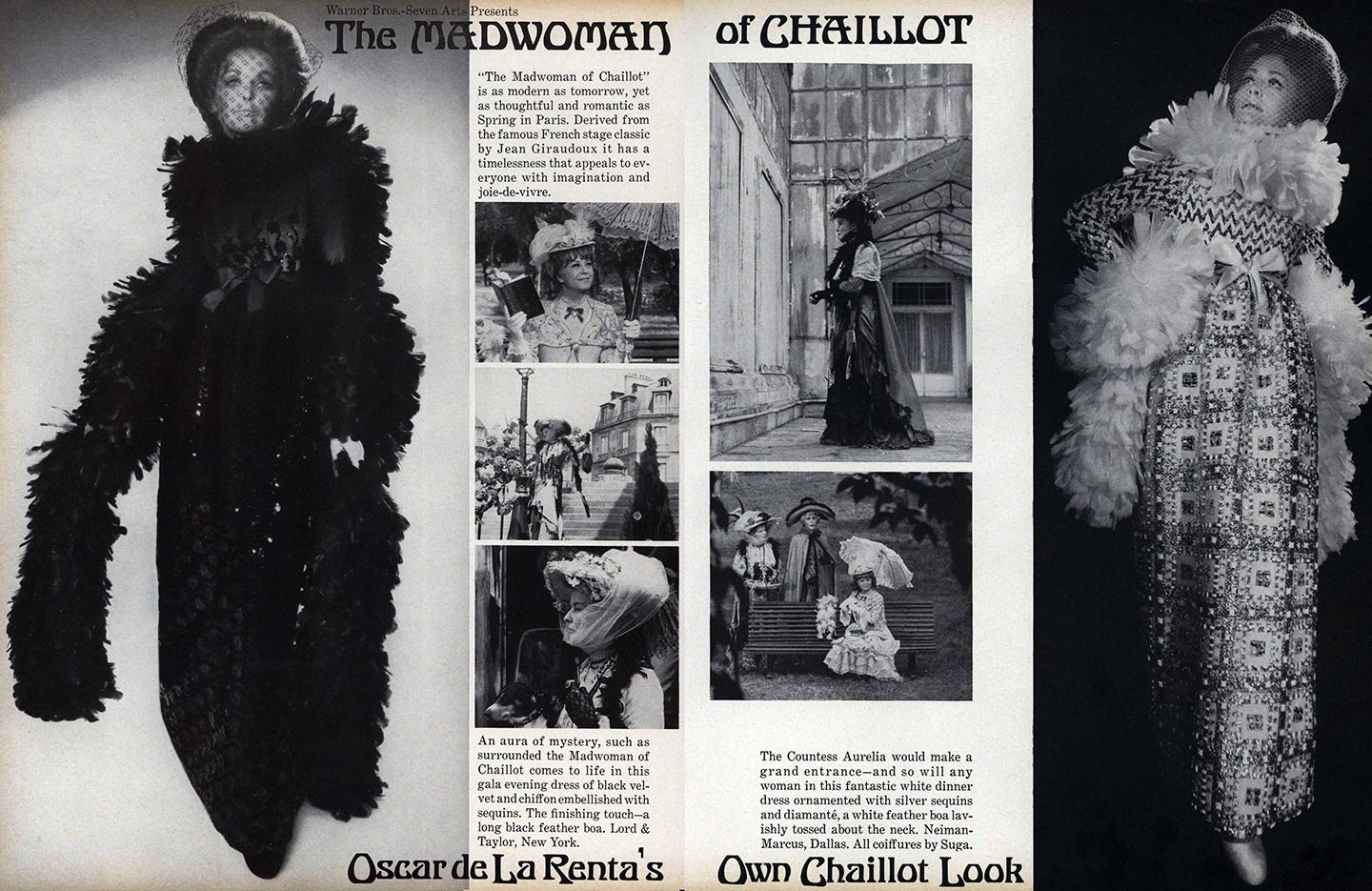

The movie Bobbie and Oscar reference is The Madwoman of Chaillot—directed by Bryan Forbes and starring Katherine Hepburn, it was released in October 1969 with distribution by Warner Bros.-Seven Arts. While set and filmed in modern day Paris, Countess Aurelia (Hepburn’s “madwoman” of the title) wears tattered-yet-chic Belle Époque costumes designed by Rosine Delamare.

Shown on May 15th, 1969, Oscar de la Renta’s fall-winter 1969-70 collection was an ode to turn-of-the-century fashions. It took me quite a lot of digging to discover if he had seen or knew of the yet-to-be-released Madwoman—none of the May reviews mention the film in their glowing prose describing Oscar’s novel nostalgia. Eventually I turned up an interview with him in the Philadelphia Inquirer that laid out his influences with a glancing mention of the mechanism behind the fashion-film deal. According to de la Renta it all started when he saw Brigitte Bardot at a theatre in Paris over the Christmas holidays: “Her hair was drawn up into a pompadour with wisps of hair around her face. I couldn’t get over how great she looked… Her pompadour stayed in my mind. I know it meant La Belle Époque clothes, so I decided to look it up in art books.”1 To begin his research de la Renta visited Rizzoli’s Fifth Avenue store, asking for a book on John Singer Sargent; when they didn’t have one they suggested a book on Gustav Klimt: “Frankly I’d never heard of him but after looking through the book, I knew that was what I was looking for.” After complaining that the Klimt book cost $125 (a quite staggering $942 today, adjusting for inflation), Oscar then went on to say he also purchased a book on the posters of Toulouse-Lautrec. Studying these volumes, he melded the coquettish outfits of Jane Avril and Moulin Rouges dancers with the reform dress styles of Emilie Flöge (Klimt’s lover and collaborator) and Klimt’s ornately patterned, gold-leafed canvases.

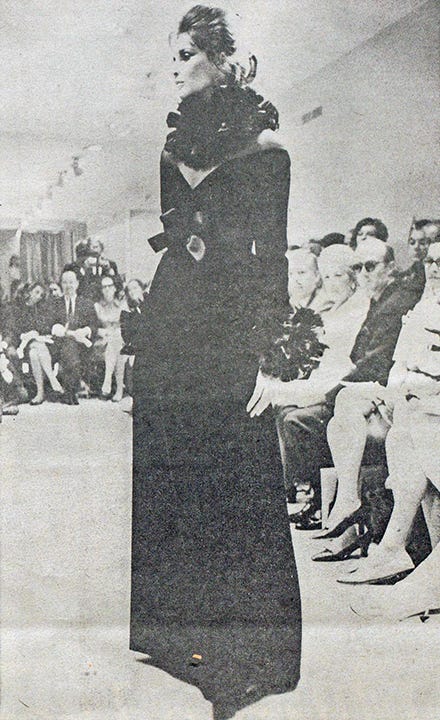

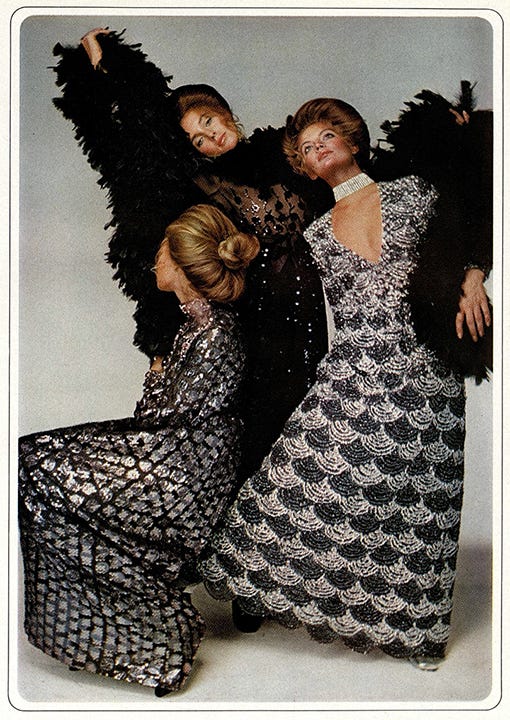

Oscar showed on the same day as Donald Brooks premiered an elaborate “Gypsy” collection, leading many fashion critics to proclaim these clothes ill-needed “retreats” from modernity—“it’s not what you would expect women to wear in the decade that put a man on the moon”—beyond finding the nostalgia reprehensible, they were also passionately against the maxi-lengths on most outfits (I’ll return to the politics of the midi and maxi in a later newsletter).2 Others waxed lyrical about the styles, finding them evocative escapism from the confusing changing societal mores of the day. Using brocaded silk, rich sequined silk, embroidered velvet and sheer chiffon (revealing just the right amount of the nude body beneath), de la Renta recreated the Belle Époque for the galas of 1969. The “models floated onto the runway shrouded in long veils and trailing full-length feather boas. They wore ten-strand pearl chokers… Gustav Klimt (called Austria’s Picasso), was the major inspiration for his colorful, abstract print fabric.”3 One newspaper vividly described the looks:

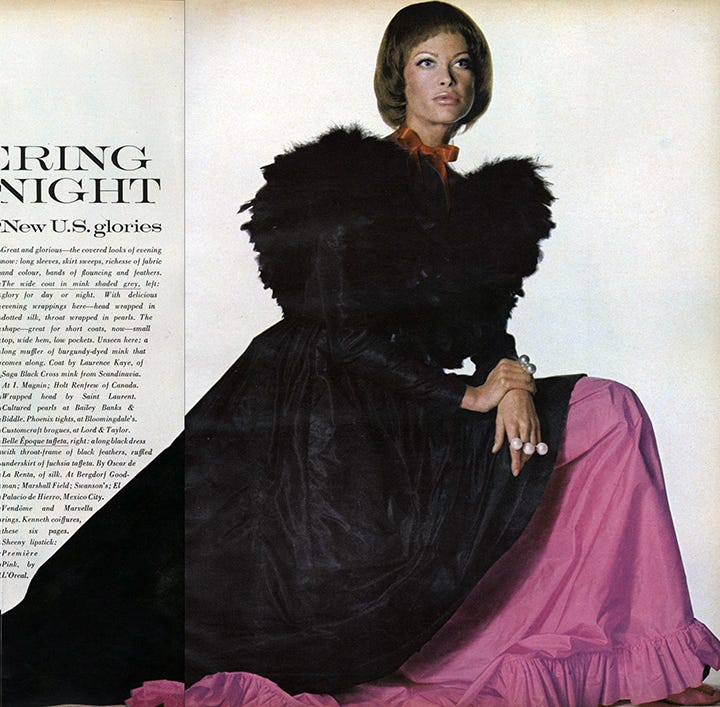

“Dramatic, swirling long black capes opened the show. They were followed almost immediately by maxi coats with long, lusciously colored, striped fur scarves. Then came fringe. Fringe that dripped from shawls covering tweed suits and fringe that hung from a jeweled leather jacket. Evening meant ruffles and feather. A black taffeta dress with a ruffled pink satin underskirt and deep V-neck outlined in feathers evoked images of the Moulin Rouge in the late 19th century. Ten-foot coq feather boas were draped around brocade dresses that could have been transplanted from Paris turn-of-the-century salons.”4

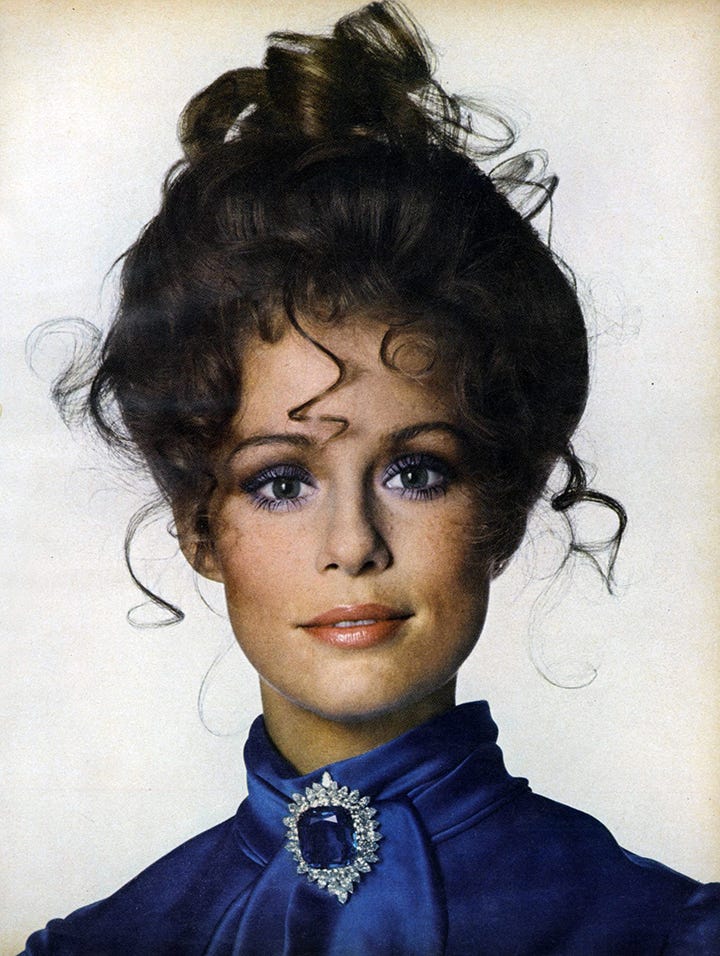

Suga, a Japanese hairstylist that had previously worked for Kenneth, replicated Bardot’s modern Gibson Girl pompadour for the show; he “swept hair up in a topknot with strands fluffing carelessly like a woman caught, enchantingly disheveled, in her boudoir.”5 Though the media seemed unable to agree on a name for it (alternating between the French concierge, the Brigitte Bardot, La Belle Époque, La Goulou, the Gibson Girl, and pompadour), by fall the New York Times was calling it “the hottest hairdo in town.”6 Vogue observed that “badly done, it is messy; properly done, enchanting.”7

Thirteen days after de la Renta’s show, Variety announced that during the upcoming Warner Bros.-Seven Arts week-long press junket on Grand Bahama Island there would be a screening of The Madwoman of Chaillot followed by a “French dinner in sumptuous surroundings” with six models displaying forty of de la Renta’s “fashions inspired by the pic.”8 It is unknown how de la Renta and W7 were brought together; what is clear is that this was an advantageous business deal for both parties—according to Variety the June 20th show was to be filmed for video outlets and clothing stores as part of a tie-in with the September issue of Vogue (traditionally the largest and most important issue of the year.) The reasons for this business collaboration come into focus within that Philadelphia Inquirer interview—the Inquirer fashion editor Rubye Graham writes, “Since most of Oscar’s customers are more interested in modern art (no one at the opening had so much as heard of Klimt), the collection will be promoted as The Madwoman of Chaillot look… although Oscar had finished the fall collection before he had heard of the Chaillot movie.”9 With little to no public recognition of the collection’s largest influence, Oscar and his team must have felt it beneficial to align the designs with a movie featuring a longtime movie star.

Within two months this tie-in had expanded—on July 28th it was shown as a “fashion featurette” on NBC from 10:30 to 11 pm, introducing the viewing public to both the upcoming movie and de la Renta’s nostalgic fashion looks in a strikingly modern manner. In an unusual turn of phrase, press photos from the event describe de la Renta’s new “look” as being “identified with” The Madwoman of Chaillot—a specific languaging that connects yet distances, further obscuring the technicalities of this business arrangement. Unfortunately I have yet to find footage from this junket fashion featurette, but you can see one of the press photos below.

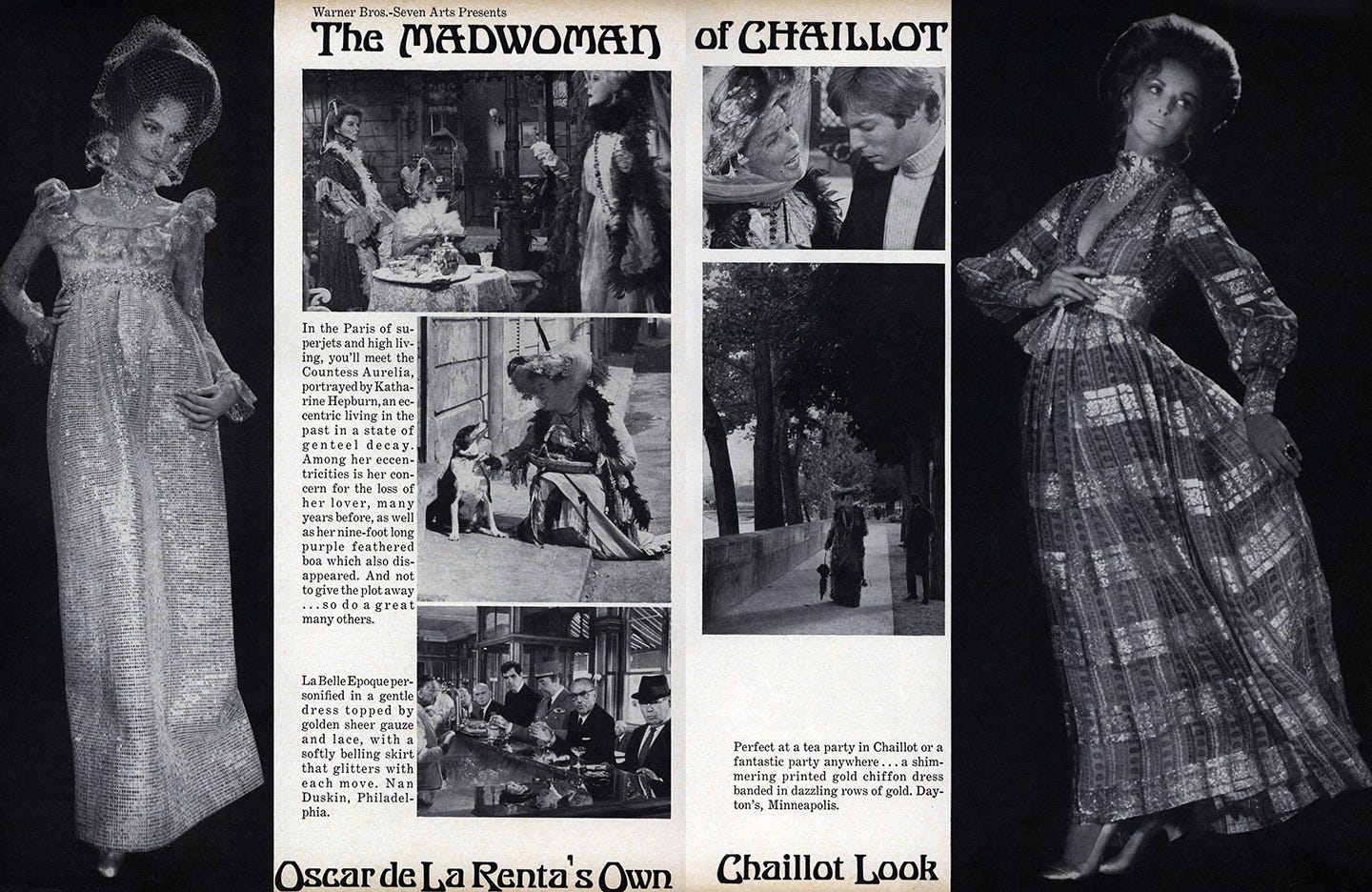

The September 1st issue of Vogue features an advertorial on The Madwoman of Chaillot and “Oscar de La Renta’s Own Chaillot Look.” Spooling across three double-page spreads, movie stills are bookended by fashion shots reminiscent of Klimt portraits. Elsewhere in this issue (and the September 15th one), Oscar’s Belle Époque designs are sprinkled throughout editorials without any movie references in the copy. The advertorial stands alone, the lasting testament to this cross-promotion.

Once the clothes started to arrive in stores, advertisements and press heavily leaned on their femininity to make sales, not the artistic influences nor the movie connection. One ad quoted Oscar: “I have been known for many years to be doing very feminine clothes, and I think that this is the most feminine collection I’ve ever made. My clothes are very, very soft, some of them very mysterious. There is not any very low décolleté. Everything is very ladylike and, still, very young in feeling. Everything that is bare is veiled, is never overexposed, is never too showy, is just an illusion.”10 His jeweled, brocaded silk gowns became a fixture all fall and winter on the gala circuit and in Women’s Wear Daily’s “Eye Too” gossip column. The influence of this collection went beyond the wardrobes of the super rich—pearls and extra-long scarves became heavily sought after. The long scarves produced for this collection by Glentex were 9 feet long by 11 inches wide, while the mink scarves were over 10 feet in length—such maxi lengths led more than one newspaper to recall Isadora Duncan’s fate.

Returning to Klimt, from our vantage point in 2021 it can be difficult to imagine a time when he wasn’t incredibly known, before The Kiss appeared on everything from pencil cases to umbrellas, and prior to the purchase of Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907) by Ronald Lauder for $135 million in 2007, the highest reported price ever paid for a painting up to that point. Due to the controversy surrounding nudity in his works, his lack of interest in travel and the relative artistic isolation he created his works in, Klimt did not start to become known in America until after the mid-century. His first solo show in the United States took place in 1959 at New York’s Galerie St. Etienne, and it was only two years earlier that MoMA purchased their first Klimt. In 1965 the Guggenheim Museum mounted a dual show of Klimt and his protégé Egon Schiele. When these few exhibitions are taken into account it becomes easier to understand how de la Renta had not previously heard of him, nor any of the guests at his May 1969 runway show.

It is common to see fashion collections inspired by movies, as well as to see designers and brands collaborating on costumes for films with real life wholesale and retail tie-ins. To my knowledge I do not know of any other fashion-film tie-in’s where a separately designed, previously shown collection was connected to a film as a marketing deal—if you know of any, please comment or email me. Oscar’s Chaillot collection appears an anomaly, a strange footnote in fashion and cinema history.

Rubye Graham, “De la Renta turns clock back,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 9, 1969, 13.

“Another fashion era,” Washington Post, September 7, 1969, 14.

Margaret Crimmins, “Designer Returns to the Romantic 1900s,” Washington Post, June 24, 1969, B1.

“Paris-Inspired Fashions Enliven In-Look for Fall,” Asbury Park Evening Press, June 25, 1969, 35.

“The Head to Turn Now,” Harper’s Bazaar, October 1969, 203.

Bernadine Morris, “To Complement Today’s Fashion - a Hairdo From the Past,” New York Times, October 15, 1969, 42.

“Beauty Gossip from All Over,” Vogue, September 15, 1969, 139.

“Directors and Players Will In-Gather At Grand Bahama for W7 Junket,” Variety, May 28, 1969, 7.

Graham.

Joseph Horne Co. advertisement, Pittsburgh Press, August 3, 1969, 99.