Lena Horne Cosmetics

Beauty, Race & Commerce

When you come across a mention of something and decide to research it, there is no way of knowing what you are getting into—how much you will find or whether you will uncover anything at all. Sometimes (like in the case below) very little comes up in up in your research—but that lack of information, remembrances, or ephemera can in themselves be revealing of what society deems worthy of recognition.

While working on my Revlon series I came across a tiny mention of Lena Horne beauty products in a newspaper from 1962. Over the years I’ve done research here and there on Black beauty brands, particularly their emergence onto the department store scene, so I was genuinely surprised that I hadn’t heard of a famous Black celebrity having a makeup line so early. I started to delve into Horne’s collection and found a very short-lived project, yet one that unfurls the history of Black beauty while foreshadowing our current glut of celebrity beauty lines.

First, a very abbreviated bio to bring us up to 1959:

Born in 1917 and raised in the Black upper-middle-class—between Brooklyn, Pittsburgh, and Georgia—Horne was exposed at a young age both to the stage and to the ripening Harlem Renaissance. Her mother was an actress in a traveling Black theatre troupe, her grandmother was a Black suffragist and founding member of the National Association of Colored Women, her uncle was president of a historically Black university in Georgia, and her father ran the finest hotel for blacks in Pittsburgh—her world was one of openness, activism, and education. Following in her mother’s footsteps, Lena joined the chorus of Harlem’s famous Cotton Club at sixteen. From nightclubs to Hollywood ten years later, her beauty, voice, and presence drew copious attention and made her a star. Dissatisfied with the limited roles available to her in Hollywood, Horne spent the 1950s concentrating on her nightclub act, headlining major clubs across the country, and appearing on TV variety shows.

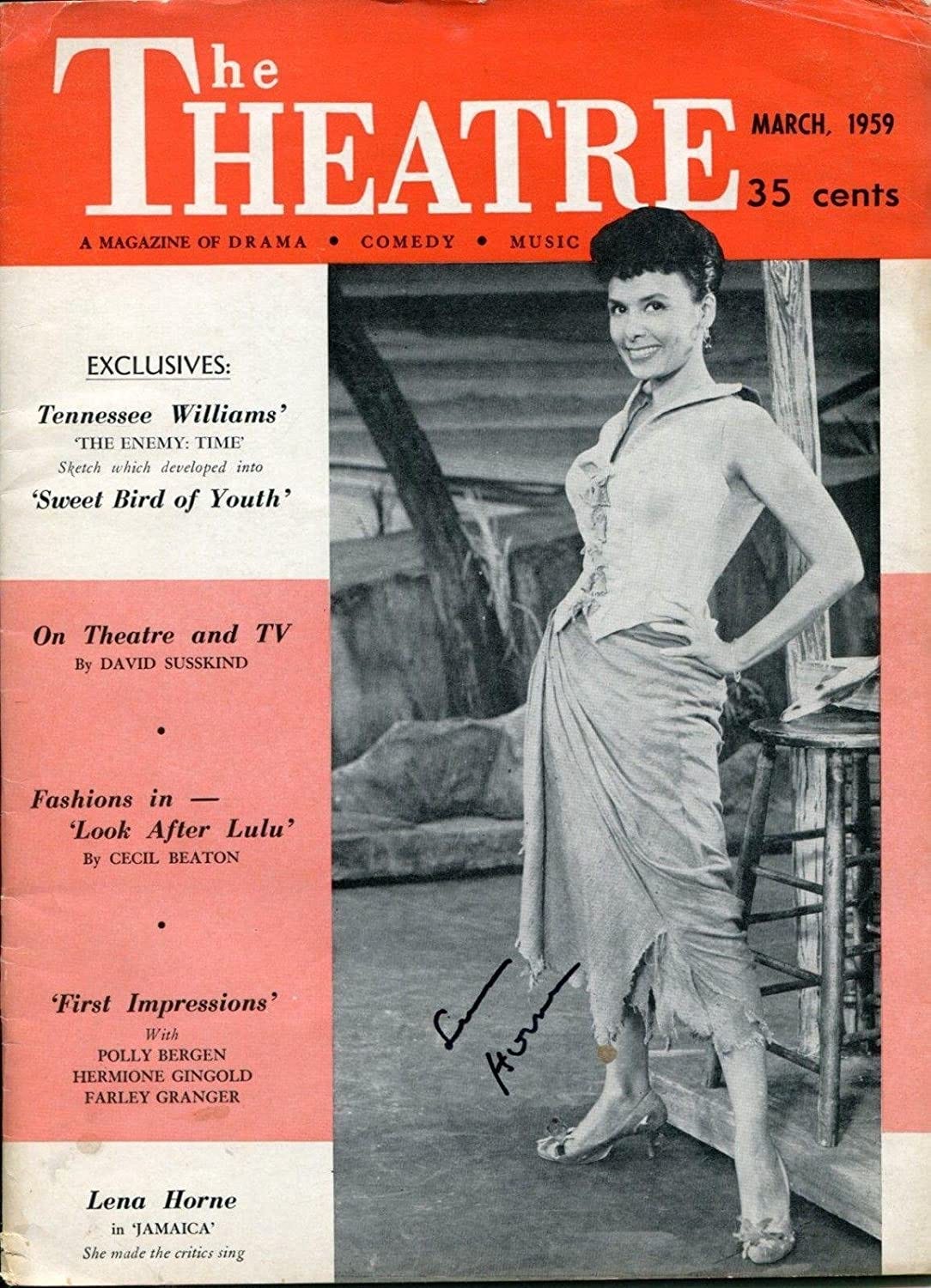

In the late 1950s, she was at one of the peaks of her fame: her 1957 live album Lena Horne at the Waldorf-Astoria was the biggest-selling record by a female artist in the history of the RCA Victor label at that time, and in 1958 she became the first African American woman to be nominated for a Tony Award for "Best Actress in a Musical" for her role in Jamaica. Since the 1940s, Horne had been heavily involved with the civil rights movement and the NAACP. Married to music director Lennie Hayton, the couple faced near-constant antagonism due to their interracial relationship. While performing on Broadway in Jamaica, her interviews center on her marriage, civil rights, and working towards equality in the arts and all of society.

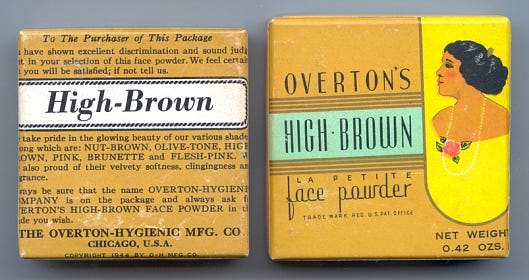

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, makeup was still completely segregated. The major brands sold in department stores and drugstores—Revlon, Max Factor, Maybelline, Estée Lauder—only produced makeup for white skins. While lip, eye and nail colors from these brands could work for any skin tone (if the woman was allowed to enter the store where they were sold), face makeup for Black women was the exclusive purview of small niche businesses. For a good overview of the development of the beauty industry for women of color, please read this 2018 Racked article by Nadra Nittle—she very clearly explicates the way racism led to the formation and evolution of these small niche businesses. When Louisiana native Anthony Overton opened Overton Hygienic Manufacturing Co. in 1898, it specialized in making and selling baking powder and other similar products to grocery and drug stores. Overton was born into slavery and soon recognized the lack of cosmetics available in darker skin tones. In the first decade of the 1900s, he began producing “high brown” face powder, which—because department stores wouldn’t stock products for people of color—was sold through mail order and a network of salespeople who traveled all over the country, visiting small stores with samples. Overton’s retail network was the operating plan for all other Black cosmetics brands (and haircare companies like Madam C.J. Walker, who recently became a Barbie doll) for the next sixty years—shut out from the traditional cosmetic retail establishments, they developed their own way. It’s important to point out that, in the early twentieth century, any cosmetics brand would have had salespeople whose job it was to travel around, pitching to stores/salons and setting up new accounts—I touch on this a bit in Charles Revson’s story, as he was a similar salesperson for Elka nail polish before he launched Revlon. The main difference is the types of accounts available, the areas visited and the price point possible. Revlon might have chosen to sell exclusively to salons in the early-1930s, before expanding to department stores, but that was exactly that—a choice. Without any options, Black cosmetics brands could only sell to stores and salons in Black neighborhoods, or through the mail.

In 1958, Horne told one interviewer, “Equality means enjoying things that other people enjoy—if you want to. It’s not just intermarriage. It’s going to the theater, or buying a dress, or getting yourself a book—if you have the loot. It’s just enjoying everything your money can buy and not having to apologize for your existence.”1 Taking into consideration the difficulties around purchasing makeup as a Black woman, it makes sense that this is somewhere Lena Horne would want to see equality as well.

Likely looking to capitalize on her famed good looks to receive a more consistent income than nightclub bookings, in 1959, Horne “entered into an exclusive agreement” with Marquard, Inc., a California-based cosmetics corporation. Marquard had been formed in 1957 by white entrepreneurs Leo Baum, Phyllis D. Griffan, Pete Marquard, Harold L. Strom, and Jewel Strom “[t]o carry on the business of development, production, manufacture and sale of cosmetics, beauty aid and allied products.”2 The corporation name was officially changed to Lena Horne Cosmetics, Inc. in November 1959 following their contract with Horne. The first mention of “Lena Horne ‘Prestige’ Cosmetics” that I found was a small ad in the back pages of the Wall Street Journal from October 1959—advertising “exclusive franchises” for a “dealer-distributor,” it promised a “big return on your investment secured by experience...” and stated that it has been “11/2 years in preparation…now ready for volume sales.”3 Other ads lay out the plan more clearly:

Available now in Washington-Baltimore area is America’s most unique franchise distributorship. LENA HORNE, star of stage, movies, TV and theatre, makes her complete line of special beauty preparations available to a distinctive market of millions (over 600,000 potential customers in Washington-Baltimore area)… Appointed distributors to organize, merchandise, train and supervise field personnel.4

Promising a profit potential of $150,000, these ads offered a “Ground floor opportunity!! In the Billion Dollar Cosmetic Industry!” Using language now more commonly connected with MLMs, immediate income and high-profit opportunities with a national organization backing it up were promised—all for an investment of between $10,000 to $40,000 depending on the area (that’s $101,813 to $407,252, accounting for inflation). The company, according to two ads, was headquartered in Oakland—the exact address no longer exists, having been consumed into the massive, postmodern Ronald V. Dellums Federal Building.

Starting the following March, small ads began to appear looking for sales ladies and managers for new franchises. The ads ranged from ones offering full or part-time employment to those requiring “house-to-house experience selling cosmetics and be willing to relocate.”5 Laid out like a pyramid scheme, the ad below uses MLM pitch techniques to convince the reader to become one of their “glamorous cosmetic consultants” who have “their own profitable, growing businesses” and can “set up their own distributorships.”6 Multi-level marketing style businesses have existed in the United States since 1945 when Nutrilite’s Carl Rehnborg invented the system to sell his company’s vitamins and supplements. Two of his independent distributors, Jay Van Andel and Richard DeVos, later founded Amway in 1959—the same year as Lena Horne Cosmetics was established. While I can’t prove that LHC was run as a multi-level marketing company, the similarity in languaging and business structure revealed in the ads hints at it while at the same time continuing the sales routes historically open to Black brands—door-to-door sales, mail order, and small networks of salespeople targeting specific neighborhoods.

In February 1960, Masco Young included the first mention of the brand (outside of ads) in his gossip column, nationally syndicated in Black newspapers: “Lena Horne’s first big attempt to cash in on the pulling power of her famous name, in her new Lena Horne Cosmetics firm, which features 22 different lines of cosmetics, with each claiming to have some of the same ingredients that have preserved Lena’s youthful looking beauty.”7 For the rest of the year, there were occasional mentions in local gossip columns but no further national stories; these gossip tidbits spoke of national consultants for the firm being feted while visiting new markets and of the possibility of a nationwide chain of Lena Horne salons to come (with Cab Calloway’s sister to supposedly open the first in Baltimore).

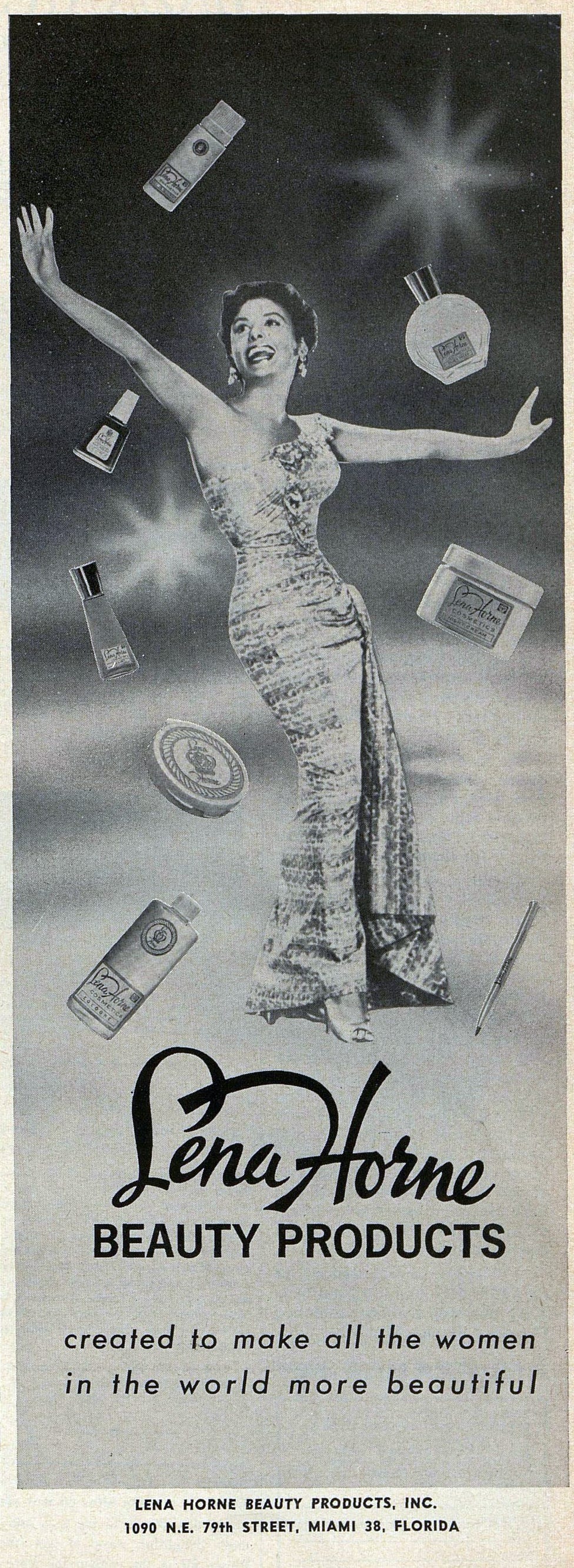

Comparing publications, one can see that the earliest ads—marketing the franchises—were primarily published in white newspapers (WSJ, Washington Post, etc.), while later ads for salespeople were published in Black newspapers (Afro-American, Los Angeles Sentinel, Atlanta World Daily). Articles and gossip column mentions were almost exclusively in African American newspapers, from cities with large Black populations. Whether the company wanted to focus first on African American markets and then expand to all races or remain exclusive to Blacks is unclear; it seems likely that American society as a whole made the former the only possible option. Though its earliest advertisements were in the mainstream media, the people who responded to those ads were all Black and living in Black neighborhoods. It appears likely that, due to Lena Horne’s race, it was assumed that the cosmetics and beauty products would be only for darker skin. The sole mention of skin color I found was in a short clip from September 1961, announcing that the “complete line of products [was] ‘created to make all…women…beautiful”, regardless of skin pigmentation.”8 This seems in keeping with Lena’s general principles of equality meaning “enjoying things that other people enjoy,” yet provides no greater clarity on the products themselves. A Lena Horne Beauty Products pamphlet, now part of Gloria Swanson’s archive at UT, reveals that liquid foundation and pressed powder compact were available in “Desert Tan,” “Natural,” “Jamaica,” or “Cocoa,” and were “advertised as shade matched to beautify black women of all skin tones.”9 While presenting themselves as a company seeking to beautify all Black women, among the nine skin care products offered was a skin lightening cream—further perpetuating the belief that lighter skins (like Horne’s own) were more beautiful and negating their proposed mission.

An April 1960 clip in Memphis’ Tri-State Defender relays that “the line of cosmetics which bears her famous name has soared to unusual popularity in the two months since it appeared in Memphis… The local office got off to such a fast start that it set a record for first sales among all offices of the beauty line across the country. The top salesman of the week here sells more than $100 worth of products wholesale.”10 A year later, the Atlanta branch celebrated its successful first anniversary—in that time it had grown from two to 116 employees including office personnel and special consultants. All salespeople attended special training classes on the products and in the “needs care of the skin” to provide expert advice to all clients; “The Lena Horne consultants also demonstrate and recommend exactly the proper cosmetics required to make each woman more beautiful, correct shades, and proper creams, lotions, and astringents for each type of skin.”11 These consultants would have come to the customer’s home, whether by appointment from the local office or as a door-to-door sales call. The apparent success of the brand in markets like Memphis and Atlanta had the company trumpeting an imminent nationwide expansion, yet in April 1961 they were still advertising the franchise for New York City, America’s largest market, requiring a $25,000 cash buy-in.

Until October 1961, there were no mentions of nor advertisements for the brand in a mainstream magazine. The below ad was published in Harper’s Bazaar, the sole advertisement of such a caliber during the company’s existence. Again, vaguely promising to make “all” women beautiful, Lena poses with her products floating in space around her; the same image (minus the bottles and jars) had been used in an Ebony magazine ad two years earlier. While Lena’s name and visage were centerstage on the products and ads, at no point did she mention the cosmetics in an interview—a strange marketing approach for a celebrity to take for their namesake products, especially when compared with the massive media circuits taken in recent years by celebrity beauty entrepreneurs. At that time, Horne was heavily involved with the civil rights movement and performing, the subject of near-constant interviews and profiles—the omission of any mention of her brand seeming to reveal a lack of interest or belief in the cosmetics.

It appears that by mid-1962, the company was finished—the Atlanta branch advertised a “going out of business” sale that July. Nine months later, Lena Horne Beauty Co. was declared bankrupt by a Miami court. According to an article discussing the sudden bankruptcy, the firm paid Lena Horne to use her name and photographs, but she otherwise was not involved.12 This likely means that the products were not based on her own specially formulated ones, and therefore probably cheaper and inferior; it also explains why Lena never spoke of the products in interviews. A year later, Lena sued the parent company, Lena Horne Cosmetics, Inc., for royalties. The Superior Court suit stated that “the cosmetics firm guaranteed under contract minimum royalties of $2,500 a year, based on 7.5 per cent royalties on gross sales, plus 10 per cent of net profits.”13 She asked for an accounting of minimum royalties. There were no subsequent reports on the case.

Aside from the lack of support from Horne, the failure of her beauty foray is likely due to a larger shift in the culture. The post-war years brought about a growing Black middle class served by new magazines (chief among them, Ebony). Not fighting segregation but instead seeking higher profits, white cosmetics brands advertised in these magazines—and due to greater resources, were able to do so much more lavishly and more often that Black-owned brands. Exposed to more ads from white-owned companies, Black women “increasingly chose to purchase cosmetics from modern grocery stores and pharmacies, instead of from door-to-door beauty consultants, who they viewed as old-fashioned.”14 Even for those still purchasing from door-to-door salespeople, there was a clear shift. The most famous direct-marketing beauty brand, Avon, began creating specific ads with Black models for use in Black magazines in 1961—these full-page and often full-color ads are striking in comparison to the quarter-size, black-and-white ads affordable for smaller, Black-owned brands, lending Avon (and companies like them) credibility and a bought-sense of efficacy.

Though a very brief and mostly unknown blip in beauty history, Lena Horne’s cosmetics company can be understood to encapsulate many major themes still at play today: colorism in beauty, celebrity-endorsed beauty lines, the performative power of beauty, and direct marketing/MLMs. Proclaimed by both the white and Black press as the epitome of Black beauty, Lena Horne sought to democratize Black beauty through her cosmetics line by extending it to all, yet her own light-skinned, European-featured face reinforced white beauty standards (especially when shown in ads as a “beauty expert” capable of solving all beauty problems). Though not the first Black celebrity to have a beauty line (Ella Fitzgerald launched one in 1957), Lena Horne Cosmetics was the first such line to be backed by national advertising and to be distributed nationwide—regardless of the brand’s failure of finances and vision, these were major firsts that helped lead the way to the famous Black beauty brands of the 1970s (like Fashion Fair and Flori Roberts) and later Black celebrity-owned beauty brands (Iman and Rihanna’s Fenty, in particular).

“Lena Horne’s Views on Race!”, Michigan Chronicle, March 15, 1958, 11.

Articles of Incorporation Marquard Inc., July 29, 1957; Certificate of Amendment of Articles of Incorporation Marquard Inc., November 13, 1959, Lena Horne Cosmetics Inc., CA-C0341825, California Secretary of State Business Programs Division, Certifications and Records, Business Entities Section.

“Lena Horne ‘Prestige’ Cosmetics” advertisement, Wall Street Journal, October 29, 1959.

“Lena Horne Cosmetics” advertisement, Washington Post, December 5, 1959, B25.

"Lena Horne Beauty Products” advertisement, Afro-American, June 11, 1960, 3.

"Lena Horne Cosmetics” advertisement, Los Angeles Sentinel, May 26, 1960, A3.

Masco Young, “They’re Talking About…”, New Journal and Guide, February 27, 1960, 1.

“Lena Horne line available to all”, Afro-American, September 30, 1961, 10.

Towards the end of my research, I came across a Ph.D. on Lena Horne that alerted me to this pamphlet along with several letters concerning the cosmetics brand that had belonged to Gloria Swanson. Megan E. Williams’ 2012 dissertation, “Performing Lena: Race, Representation, and the Postwar Autobiographical Performances of Lena Horne”, was invaluable in discovering these and learning about the brand’s investors/owners. Lena Horne Beauty Products, Inc., Product Pamphlet, May 1961, Gloria Swanson Papers, RLIN Record #TXRC93-A8, Box 205, Folder 10, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

“Lena Horne Cosmetics Soar in Popularity”, Tri-State Defender, April 23, 1960, 3.

“Lena Horne Cosmetic Products” advertisement, Atlanta Daily World, May 19, 1961, 2.

"Lena Horne Beauty Co. Is Bankrupt,” Michigan Chronicle, April 20, 1963, B11.

“Lena Horne Sues Cosmetics Firm”, Women’s Wear Daily, September 18, 1964, 12.

Megan E. Williams, “Performing Lena: Race, Representation, and the Postwar Autobiographical Performances of Lena Horne”, PhD diss., (University of Kansas, 2012).