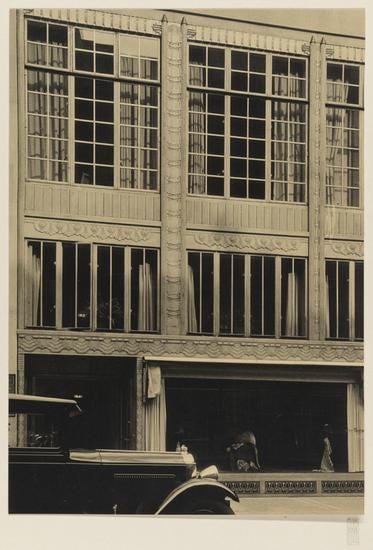

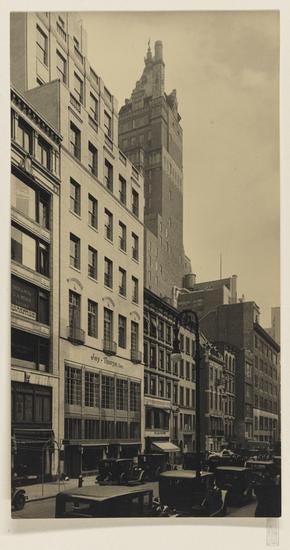

Sometimes it seems like when you are researching that no matter how hard you look, you can’t find the thing you need—but then when you publish, the information appears in the oddest place or in somewhere you know you already looked. After I published last week’s piece on the Lalique room at Jay-Thorpe and while I was finishing up Sunday’s article on Raymond Loewy’s spaces for Jay Thorpe (they appear to have dropped the hyphen sometime in the 1930s), I found clearer images of René Lalique’s 1928 designs.

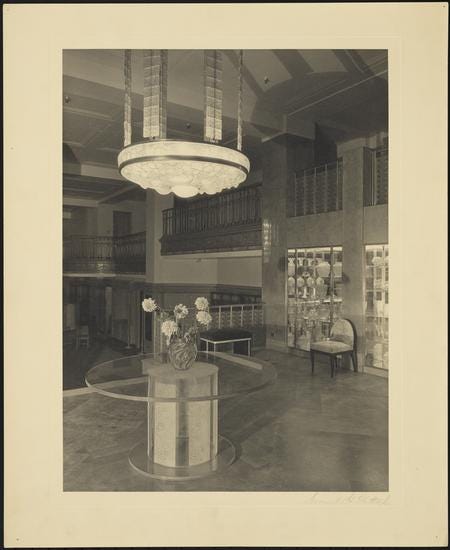

While these aren’t as high res as I would like, they provide a much clearer understanding of the room—quite simple in design and layout, but elevated through the use of luxurious materials and sumptuous surfaces that draw the eye to the sparkling, lit glassware. In such an elegantly bare space, Lalique’s work is shown to the best advantage; there are no distractions, ushering in the sensation that it is more an art gallery than a shopping establishment. The very simplicity was incredibly modern—a casting off of the overstuffed interiors of decades past—and a signal that the store was expensive and successful enough that they did not have to overload the space with stock in order to make sales; the very definition of luxury retail.

Below is an extract from a 1929 article on him, which helps to orient Lalique’s work within society and the art/craft world of the period.

Lalique - Modernist in Glass: A Study of the Work of a French Genius Who Uses an Old Medium to Strike an Entirely New Note in Art

by Adeline L. Atwater, The Atlanta Constitution, April 14, 1929.

Even if this great craftsman had confined his unlimited energies only to the objects displayed in his store, he would still be one of the leaders in contemporary art. But he is a far more significant figure—in a peculiar sense he typifies the most wholesome esthetic trend to-day.

If the word modern suggests to you bizarre or eccentric designs, geometrical cubes and angles, then Lalique is not a modernist. His eye seems full of a quite ancient vision—he loves the dainty human figures of Pompeian paintings and vases. He likes to assemble natural objects in the decorative idiom of Japanese art. Birds, fishes, peacock feathers, flowers—these are all he needs for his motives. In fact, like the Oriental masters, he seems content to use the patterns which nature in her most obvious moods, strews at our feet. He is undisturbed if these patterns are already long familiar; the desire to escape from the normal apparitions of life is not in him.

But. in a more important way, he is a modern of the moderns. He has dared to introduce his art into those departments of life which we are too often content to furnish with machine-made conveniences. He sees no reason why the doorknobs we turn, the knives and forks we use, the tools or instruments of our most ordinary moments should not be beautiful. Not only beautiful but, in a French way, individual. He represents in our time the point of view held by a few great geniuses in the Renaissance, and advocated in England by William Morris, that the distinction between fine and applied art is false.

This is at once the most democratic and the most aristocratic view of art. It assumes that all objects associated with human experience are available for the expression of beauty. It assumes also that we, the common run of men and women, would enjoy beauty if we could have it on all sides of us. Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Cellini and the others served a few choice patrons. William Morris, by his personal energy, managed to put into practice a large part of his theory, but he himself was an aristocrat, antiquarian in his tastes, a little out of sympathy with the world his art was to save.

In fact, Morris wished to transform society in order that it might reach the spiritual vision necessary to appreciate him. Society, on the whole resisted the reform, and has pretty nearly forgotten him. René Lalique by contrast seems curiously in touch with the world he serves, though his own life is that of a recluse. He serves the modern world as it is, with complete sympathy. It is not surprising, therefore, that his work has an enormous welcome in his own country and seems likely to influence modern crafts everywhere.