High on my mind lately has been the major interior decoration schemes at Jay Thorpe, a New York woman’s specialty store which was open from 1920 to 1961. Today I will be laying out a short history of Jay-Thorpe, their building, and an addition by a famed designer that took place in the 1920s; in a few days, I will be exploring the opening of another addition in the mid-40s with an interior designed by one of America’s most famous industrial designers.

In May 1920, the incorporation of Jay-Thorpe was announced. Developed by Charles J. Oppenheim (of the family behind the NY department store chain, Oppenheim Collins & Co., and the “Jay” in the name) and Mae Thorpe (previously a buyer at Bonwit Teller), the new owners stated that it was to be a “specialty shop dealing in high grade women’s apparel, dry goods, millinery, cloth and fabric manufacturers, boots and shoes, hosiery, import and exports”—of the major stores still existent in NYC from this period, Bergdorf Goodman (minus the men’s store) is the closest in purview to Jay-Thorpe. Unlike many other high-end stores at the time, Jay-Thorpe was not to have a couture salon; as Mrs. Thorpe told Women’s Wear, “The business of Jay-Thorpe is to be strictly ready to wear. We believe in doing one thing and doing one thing well. There will be no special order dress department, we will not pretend to do a dressmaking business…”

At 24-26 West 57th Street between Fifth and Sixth, they started construction on a nine-story building that was to hold six floors of retail and wholesale spaces, along with workrooms and offices; the additional floors were to be let out. The Georgian-style building was designed by Buchman & Kahn with a white marble façade and wide windows. After approximately four months of work, Jay-Thorpe was ready to open to the public on October 18th. The ground floor was devoted to millinery with portions reserved for blouses, novelties, and perfumes. Designed in the neoclassical Adam style, with a warm gray finish, hardwood floors, and “rugs to harmonize with the furniture.” Wide open and inviting, there were only two display cases and a few tables for ease of movement; the stock was carried in closed cases at the sides. Around the rear and side of the space was a mezzanine level, with offices. The second floor was given over to gowns, frocks, and wraps—the evening gowns allotted a section in the back with special dressing rooms. As with the ground floor, the furnishings were from the Adam period, with gilding. Most of the stock was to be kept hidden, with just two set-in cases on display. The third floor was divided into three parts. The front, in Louis XVI style, sold lingerie and negligees. The back was split between furs and sportswear, both decorated in Tudor Oak. The fourth floor, again in the Adam style, was a fitting and reception room, used for all refittings. The two floors above were to be occupied by workrooms and stock rooms. According to Women’s Wear, “the general construction with arched ceiling and Renaissance pilasters, forms an inconspicuous background to the fittings. The attempt to make the shops individual is notable.” The Fifth Avenue Association awarded the building a medal for its excellence of design.

“The aim of Jay-Thorpe is to present to their clientele offerings rather more excellent than the usual, and in the most appropriate and refined surrounding. With this in view they have erected a splendid building which stands out prominently on the Rue de la Paix of America, by virtue of its sheer beauty and simplicity.” – Jay-Thorpe ad, October 13, 1920

By all appearances, Jay-Thorpe was a success from the start—with its hats particularly acclaimed. That winter, Jay-Thorpe began opening annual seasonal shops in Palm Beach; in later years, they added a winter shop in Miami and a summer store in Magnolia, Massachusetts. Due to many new and important retail establishments, like Jay-Thorpe and Henri Bendel (at 10 57th), Fifty-Seventh Street was widened from forty to sixty feet in 1923 to create a “boulevard of trade.”

The company was doing so well that in 1922 they purchased two lots on West 56th Street, directly behind the Jay-Thorpe building; in September 1927, they began construction on a nine-story building that was to add 300,00 square feet to their retail and business space—the buildings were to be attached so that customers could move between them easily, but there were to be separate entrances with clearly defined aesthetics. Buchman & Kahn were again hired as architects, but Jay-Thorpe brought in someone very special for the interior of the ground-floor salon at 25 West 56th: the famed French jeweler and glassmaker René Lalique.

When Jay-Thorpe’s new building opened on September 10, 1928, customers were greeted by the height of luxurious modernism. It was the first of Lalique’s interiors in America, though Lalique had designed a perfume flacon for Jay-Thorpe that premiered in 1927. Carried out in “etched glass, metal, and bruised maple”—described as a “beautiful pale, amber-color wood with a high luster”—one entered through etched glass doors into a salon lined with well-lighted cases displaying Lalique vases, perfume containers and other glass objects. About halfway through the space, “the salon hangs like a balcony above the rest of the main floor,” which was at a lower level and reached by a wide marble staircase. Hanging above were six cylindrical glass chandeliers around a central, very large chandelier fashioned from a glass bowl suspended on rods decorated with etched glass in a fruit design; the smaller chandeliers were etched in bird, flower, and fruit designs. The chairs around the room were upholstered in Rodier fabrics.

Note: Better photos of the Lalique rooms can be found here.

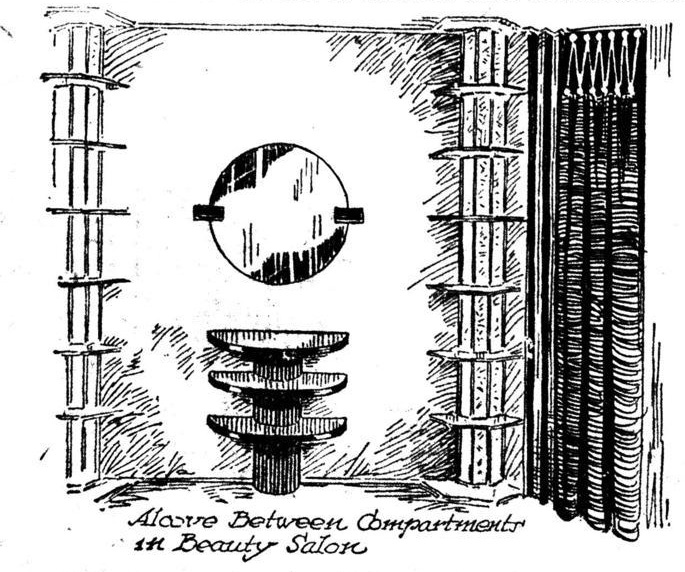

On a mezzanine above the salon and lower main floor was a walkway with executive offices—screened by Lalique etched glass—as well as two booths for Chanel facials and a special customer’s lounge. Jay-Thorpe had the American exclusive for facials using Chanel products, and the esthetician had been trained under Gabrielle Chanel in her Paris shop; in addition to facials, she was also trained in “the selection of a perfume suited to one’s individual type.” According to Vogue, Lalique also designed the beauty salon interior—the two booths flanked an alcove with tall glass cabinets showing off Chanel ointments and scents, which were also arrayed on a semi-circular mirrored shelving unit hanging below a circular mirror. Women’s Wear Daily called Lalique’s interiors, “one of the best, if not the best example of applied contemporary decorative art (in glass) to be seen in New York City.”

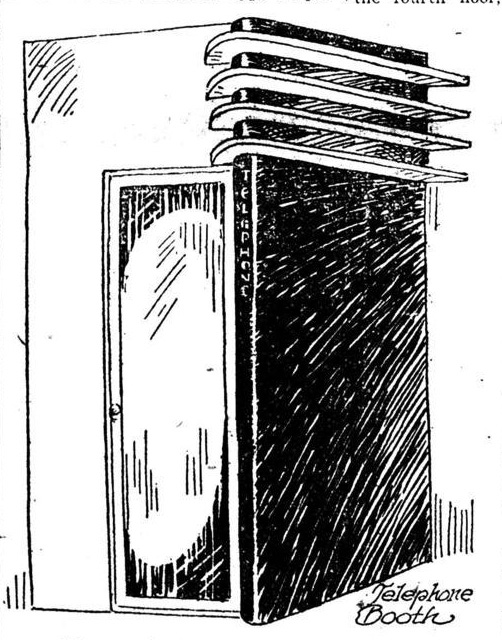

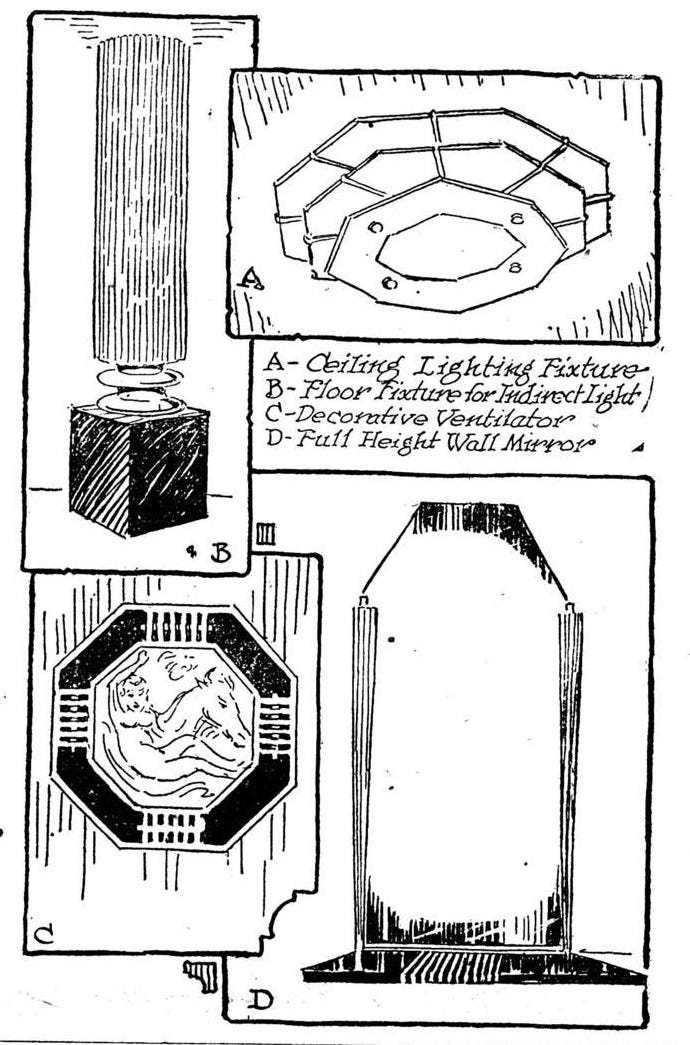

The modern mood extended through the rest of the new building, though René Lalique was not behind those interiors. All public spaces, other than the main glassware salon and beauty area, were designed and decorated by Whitman & Goodman, though it does appear that Lalique oversaw all the lighting. Also on the mezzanine was a special customer’s lounge that was described by Women’s Wear Daily as being in the “modern spirit.” They continued: “Electric bulbs concealed within tall, hollow, opaque cylinders throw the light upward toward the ceiling… A wall medallion of beaten metal, designed by J. Franklin Whitman, Jr., of the firm of Whitman & Goodman, adorns a black wood, screen-like wall at the head of the salon. At the opposite end stands a tall primitive sculptured figure in wood. Modernistic letters in metal direct the eye to a novel telephone booth at one side of the lounge, the exterior done in black and silver and the interior lined with turquoise blue.”

Upstairs, the second floor was divided into two parts. The fur salon had “walls of silvery English harewood and ceiling coffered with silver cross-bars and equipped with frosted lights, imparting to the whole and appropriate frosty atmosphere,” as well as four fitting rooms of the same figured wood and frosty glass. “An especially interesting feature of this salon is the carved and perforated glass ventilators running about the walls of the room, close to the ceiling,” as shown in the illustration below. Also on that floor was a new department for debutante and sub-debutante dresses, lined with tawny natural mahogany and honey color maple to create a much warmer backdrop than the neighboring salon. Hanging over the doorways were Rodier fabrics “in which the dominant shade of blue reflects the ground color of the carpet.” On the walls was painted a large mural, also by Whitman, of “two moderns picnicking [sic] under a tree,” which was said to sound a “note of liveliness.”

The third-floor coat salon appears to have been quite a grand situation, melding the very new Art Deco style with ancient Greece. “A semi-circular colonnade at one end at once traces the design to Greek inspiration. Mauve-tinted walls, a gray-mauve carpet, furniture in purple-brown amaranth [sic] wood, and ebony doors with flat columns fluted in silver comprise the chief appointments. Seven fitting rooms, leading out of the semi-circular portico and running about the sides of the salon, correspond in constructional detail with the main salon and match it in design.” The rest of the new building was devoted to workrooms, executive offices, an enlarged millinery atelier, and enormous cold storage for furs.

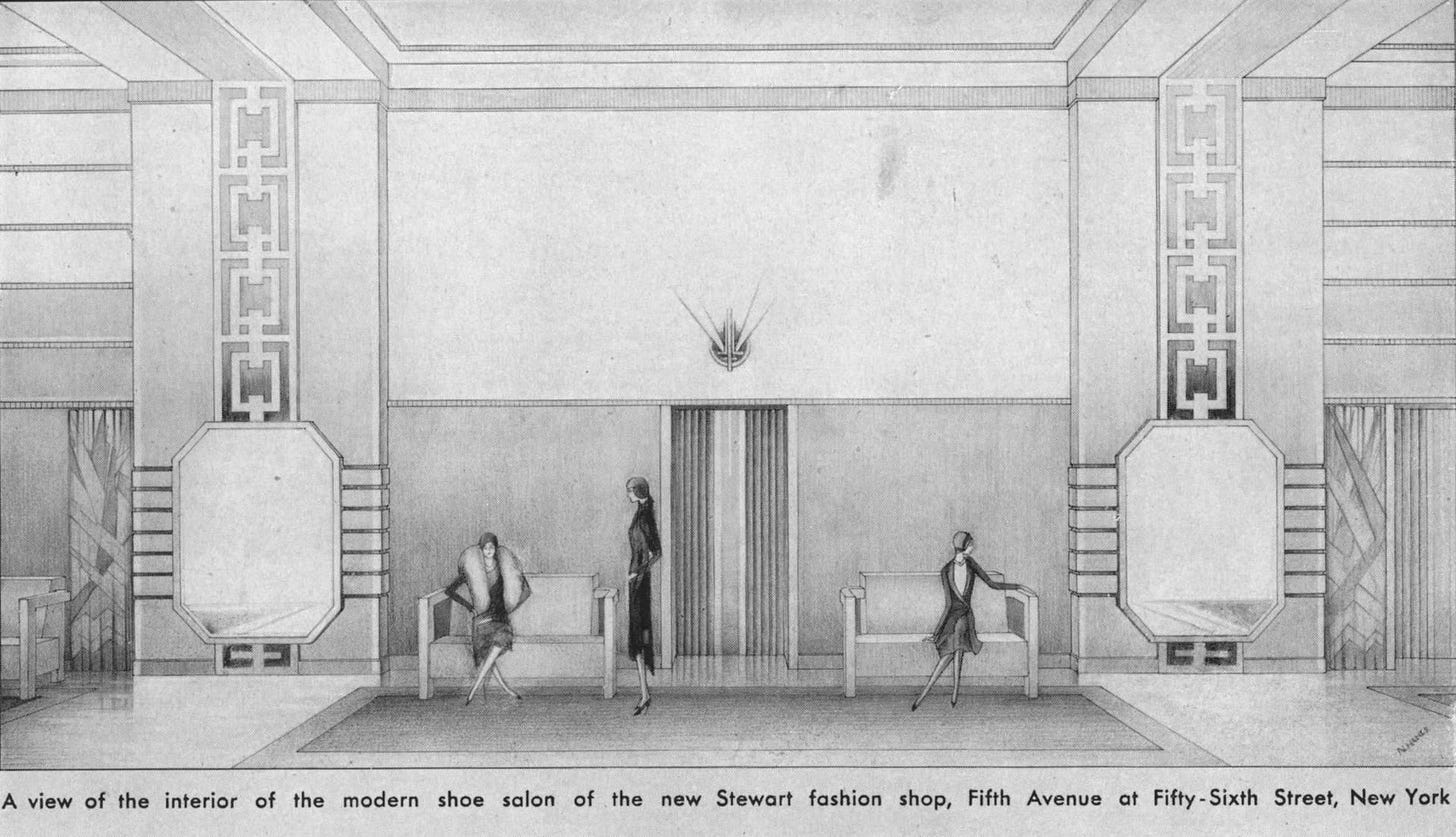

The beauty of Jay-Thorpe’s new addition brought praise not just to Lalique but also to Whitman. He was soon hired to design the interior of Stewart and Company’s new department store on 5th and 37th Street. The height of Art Deco sophistication, it opened with a gala luncheon on October 15th, 1929; thirteen days later the stock market crashed, and by the spring Stewart and Company had declared bankruptcy. Bonwit Teller took over the building, removing Whitman’s highly praised interior. Jay-Thorpe fared better than Stewart, routinely releasing higher-than-expected takings in the years following the crash. In 1931, the shoe department was moved into the “Lalique room” with perfumes and Lalique glassware moved to the 57th Street side; the Lalique chandeliers and fittings were retained.

After this, I found no further mention of the “Lalique room” and all of its one-of-a-kind glass. What happened to it all? Online compendiums of Lalique’s work do not include any acknowledgment of the whole project, and the chandeliers and other fittings appear to have been lost to history. That salon was likely remodeled when tastes changed away from Art Deco; we have to hope, at least, that someone considered these then-unfashionable pieces worth saving.

To think that I was right across the street, at 30 W 56th Sr., for 30 years,

In the old Seligman mansion, with absolutely no idea of the existence of Jay Thorpe🙄🙃