For an introduction to Katy Keene, please read my last newsletter.

“Hey kids, send in your own fashion cut-out designs for Katy.” When Bill Woggon placed that request in a late 1940s comic book, he had no sense that he was creating the fashion subconscious of a generation. For children and teens growing up in the 1950s, Katy Keene was a site of fashion experimentation, flamboyance, and creativity. Creatives like Willi Smith (b. 1948), Betsey Johnson (b. 1942), and Antonio Lopez (b. 1943) grew up studying the pages of her comics—lingering over every look, their fashion worldviews were formed by the over-the-top expressiveness of the reader-designed ensembles.

By the late 1970s, the 1950s had already cycled back into fashion several times. As early as 1967 there were rumblings of a fifties revival in both fashion and popular culture. When tour promoter Richard Nader announced “The 1950’s Rock & Roll Revival” concert of all famous (and out-of-fashion) Fifties musicians for October 1969, it was expected to flop. Instead, it proved to be a nostalgic juggernaut—the first show at Madison Square Garden took place before a sellout crowd of 9,000, leading to a cross-country tour grossing over $5.5 million and inspiring a rockumentary, Let the Good Times Roll. Young adults who remembered yet were too young to participate in the 1950s and teens who were too young to remember flocked to the shows, dressed to the nines in thrift store garb. The original musical version of Grease premiered in 1971, before making it to Broadway in 1972. In Britain, a Teddy Boy revival in the early Seventies centered around Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s Let It Rock boutique, which sold proper Edwardian-fashioned Drapes. As quickly as the 1950s cycled into fashion, it cycled out—and cycled back in again a few years later. “Nostalgia is a very powerful thing, a very powerful motivating force, but very temporary. It’s like a big flash and it goes right away,” Nader told the New York Times in 1973.1 Other than “Happy Days” on TV, the mid-1970s was a mostly fallow period for fifties fashions and pop culture before a resurgence of interest surrounding the release of the movie adaptation of Grease in 1978.

Speaking of the fifties nostalgia trend in cinema (seen most clearly in George Lucas’ American Graffiti, set in 1962 but vividly portraying the last gasps of the previous decade, and The Last Picture Show), the critic John Russell Taylor wrote in 1977, “The first aspect of the fifties that appealed to nostalgia was the mood of innocence. Naturally, kids in those days (at this point it was mainly kids and their world that occupied filmmakers and the creators of television series like “Happy Days”) thought they had problems and believed they were very daring and sophisticated. But what did they know? That was before—before drugs and long hair and Vietnam and the rock revolution. It was ponytails and high school proms and sodas and the twist—ah, happy uncomplicated days indeed!”2 These currents similarly flowed through fashion. Russell continued: “And, of course, the nostalgia first expressed was extremely personal: This was the childhood and youth of the generation now making movies, and what they remembered, through rose-colored spectacles, was a relatively uncomplicated world.” Recalling a time when they were too young to be aware of the political undercurrents, the 1950s that found its way into fashion was that of a wide-eyed child taking in an adult world—glamour and beauty as reflected in a comic book.

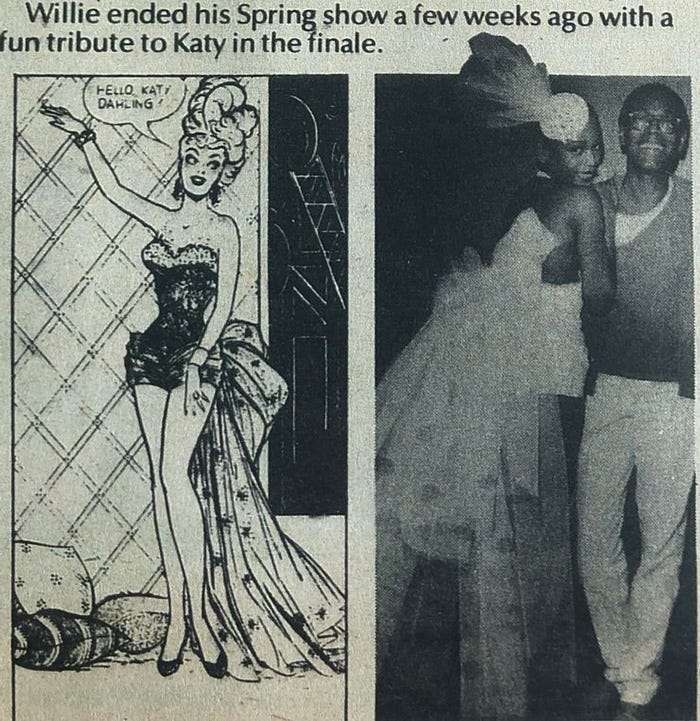

As I mentioned in my previous newsletter on Katy Keene, all of the fashion model’s clothes in the comic book were sent in by fans. Children, pre-teens and teens poured their artistic visions into wardrobes for Katy, her friends and family, and then patiently waited months to hopefully see their ideas replicated on the pages of their favourite comic. As a child, Willi Smith sent in “several hundred a month, and once won a butterfly fashion contest.”3 Smith considered her “my Vogue, total fantasy. She was white Diana Ross. She was always going to a party, even during the day. I always wondered, ‘Where and how did she get those fabulous clothes?’”4 Betsey Johnson sent in ideas, but hers were never used. Neither were any of the sketches that famed fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez sent in as a teen. Even without the validation of an outfit being chosen, the very act of coming up with and creating sketches for Katy placed Johnson and Lopez on their artistic paths. The glamour, creativity and individuality that both are known for within their work can be seen as the next evolution of the endlessly fashionable and creative Katy Keene. Antonio said in 1979 that he had never forgotten Katy’s “tight pants, hats, and, especially, her outrageous shoes.”5 As a fashion illustrator, Antonio emphasized and exaggerated items such as these, creating the drama and outrageous styling he had so admired in Katy. Similarly, according to a comment his wife left on my Instagram the other day, the avant-garde fashion designer Larry Legaspi had also been a fan of Katy’s ensembles in his youth.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sighs & Whispers to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.