If you were a kid interested in fashion and art in the 1950s, you were probably a fan of Katy Keene comic books. The beautiful raven-haired model starred in comics with one special feature—all her clothes and many of her poses, cars, interiors, and themes were created and sent in by loyal child and pre-teen fans.

Ohio-based cartoonist Bill Woggon created Katy in 1945. As a child, he had become fascinated with a federal art correspondence course taken by his elder brother Elmer and began to draw constantly in his free time. When Elmer got the job as an art director at the Toledo Blade newspaper and began drawing his own comics (most notably Big Chief Wahoo, which later became Steve Roper and Mike Nomad), Bill assisted him with lettering and other small jobs. He dropped out of high school at sixteen to become the art director at Tiedtkes Department Store in Toledo. Bill took over much of the cartooning of Big Chief Wahoo, leading to a connection with a newly launched comics publishing company, M.L.J.

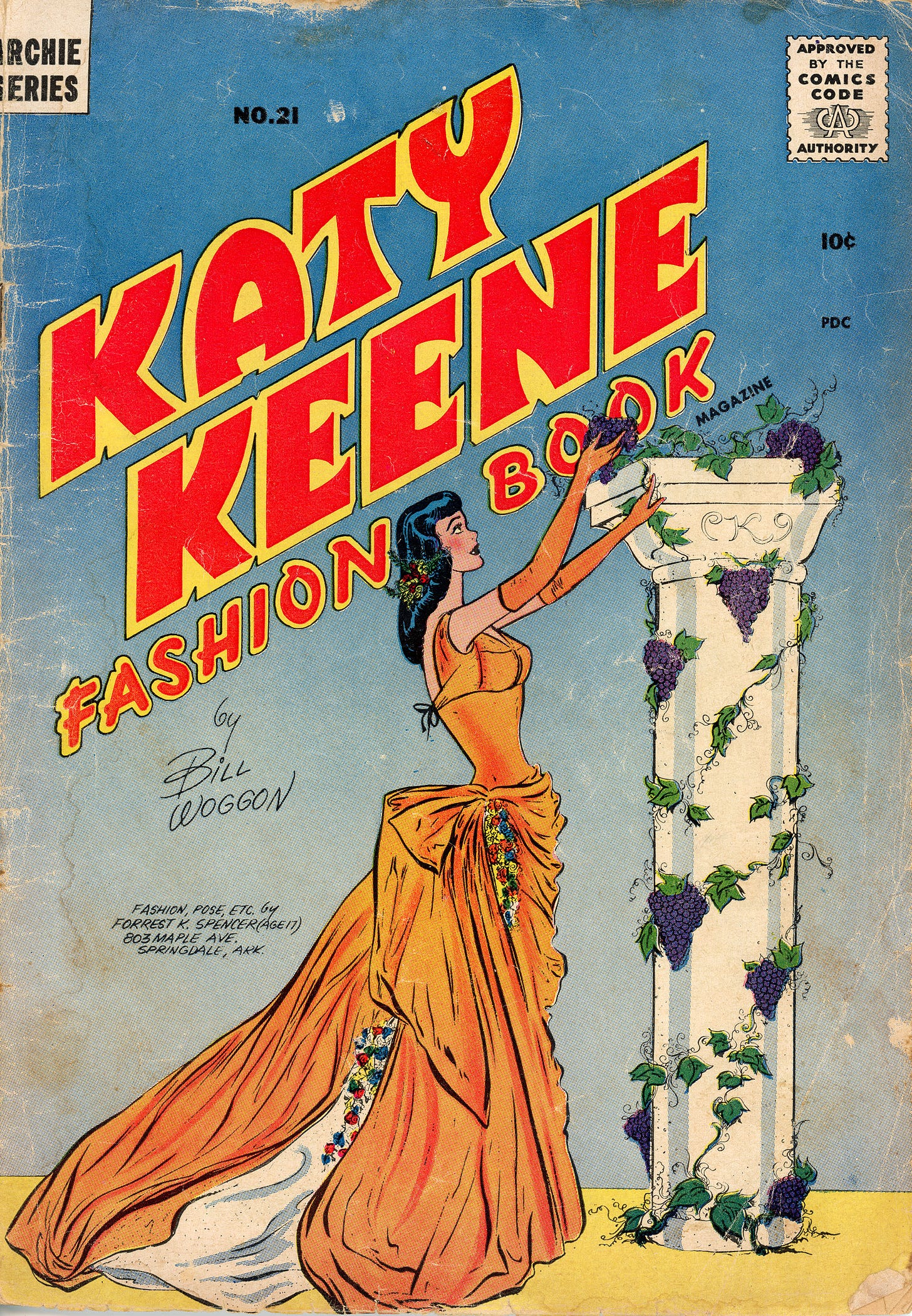

The vaguely Betty Page-ish beauty was inspired by wartime pin-up girls. Keene was launched in the fifth issue of Wilbur Comics, a teen boy contemporary of Archie (actually pre-dating him by three months), in the summer of 1945. Over the next few years, she made a number of appearances in M.L.J. Magazines, Inc./ Archie Comic (the name changed in 1946 due to Archie’s popularity) publications including Archie, Jughead, Betty and Veronica and Ginger, before her own comic premiered in 1949. Katy Keene Comics ran for sixty-two issues, briefly titled Adventures of Katy Keene (#50–53) and simply Katy Keene (#54–62), until July 1961. Additionally, there were fifteen issues of Katy Keene Pin Up Parade (1955–1961) and thirteen issues (#1–2, 13–23) of Katy Keene Fashion Book Magazine (1955–1959), along with several annuals and specials.

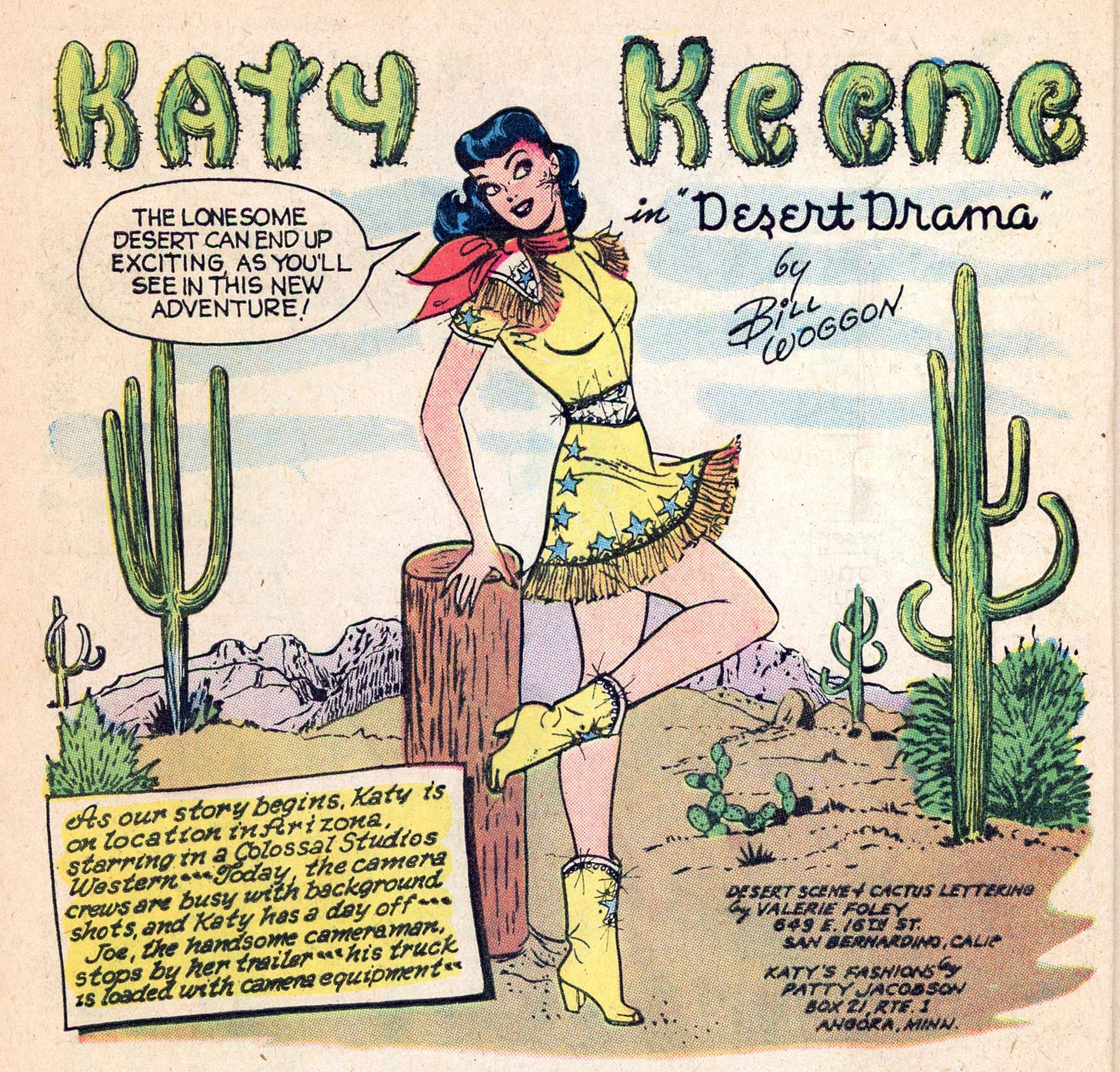

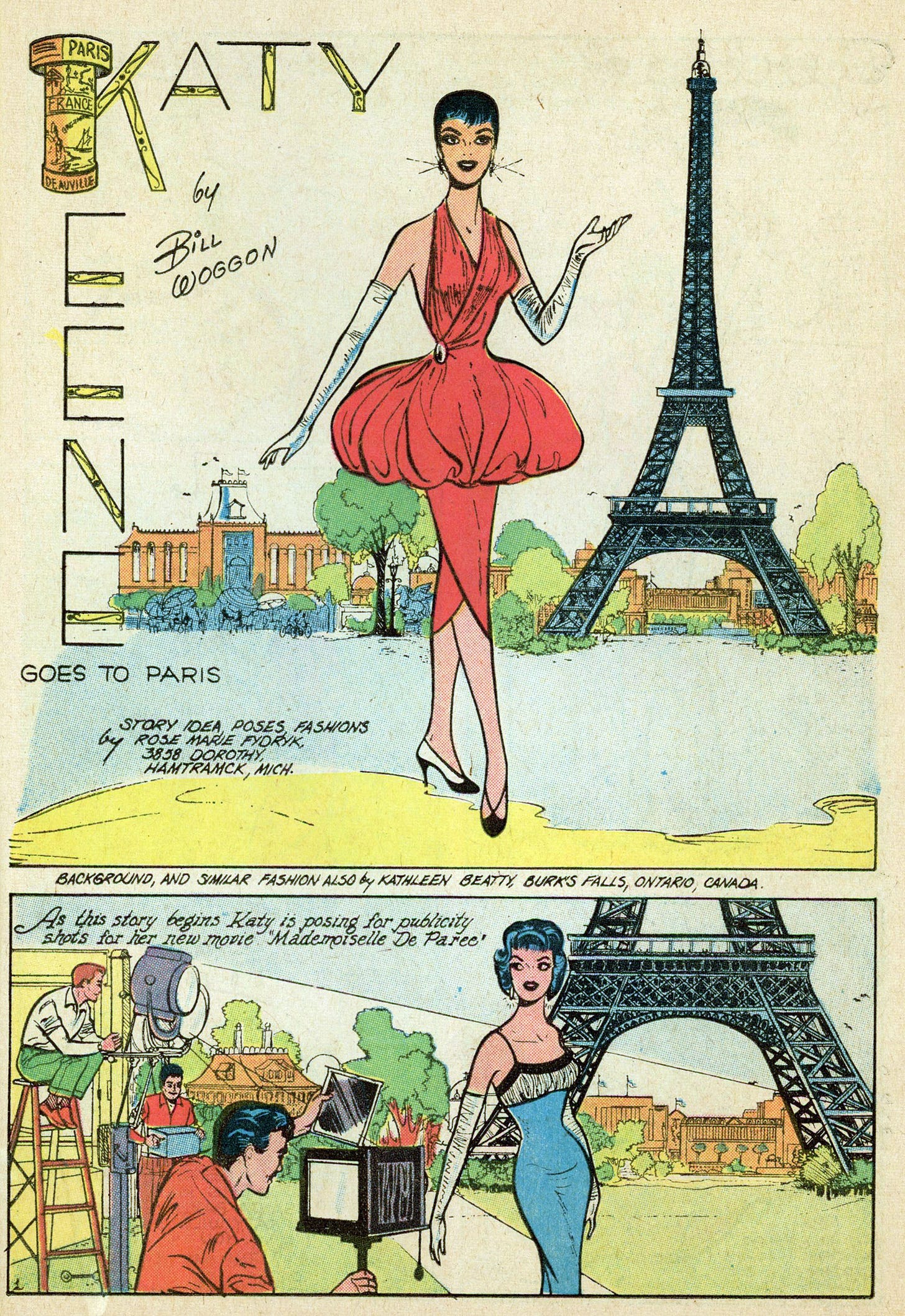

A good-girl fashion model who aspired to movie stardom, Katy’s storylines revolved around her many suitors, rival models (“the wealthy and snobby blonde Gloria Grandbilt and her best friend is the superstitious redhead Lucki Lorelei”), and her mischievous kid sister. Woggon took his family on a vacation to California in 1948 to research Hollywood for Katy’s comic strip. According to his son Bill Woggon Jr., “In 1948, the family [took a vacation to California] to see MGM studio and to tour other studios… We took a side trip to Santa Barbara. Back in Ohio, we took a family vote and decided to move from Ohio to California. After we moved to California, more of the [Katy Keene’s] script took place in Hollywood.”1 After purchasing a tract of land in the foothills near Santa Barbara, he set up Woggon Wheels Ranch. On the ranch he worked out of a small stable; his daughter Susie Bothke later recalled, “The studio was not very big at all. [It was just big enough for] Dada and the two gals that worked for him that would help do the artwork. It was yards from the house. We had both parents at home. [The studio] was not real advanced by modern standards. There was a drawing board for each one, and filing cabinets. He kept clippings for ideas for everyone or copy. There was something to hold pens or pencils in. All that [necessary cartoonist] stuff: rubber cement and erasers. There were braided throw rugs on the floor. Not a real furry [ed: fancy?] place. It was a working place.”

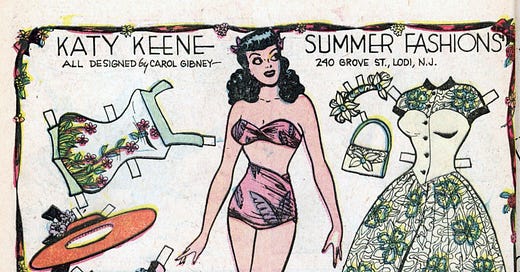

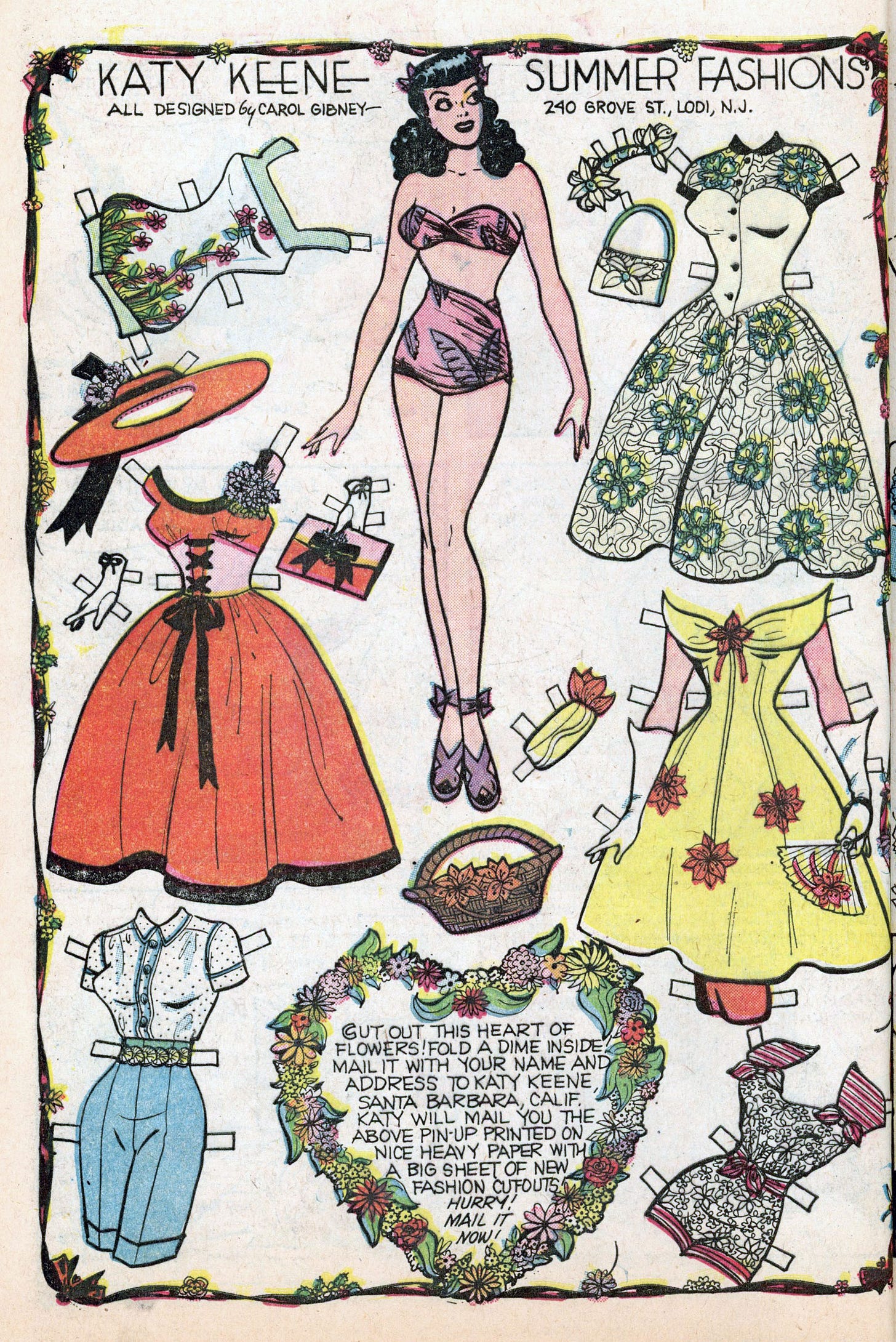

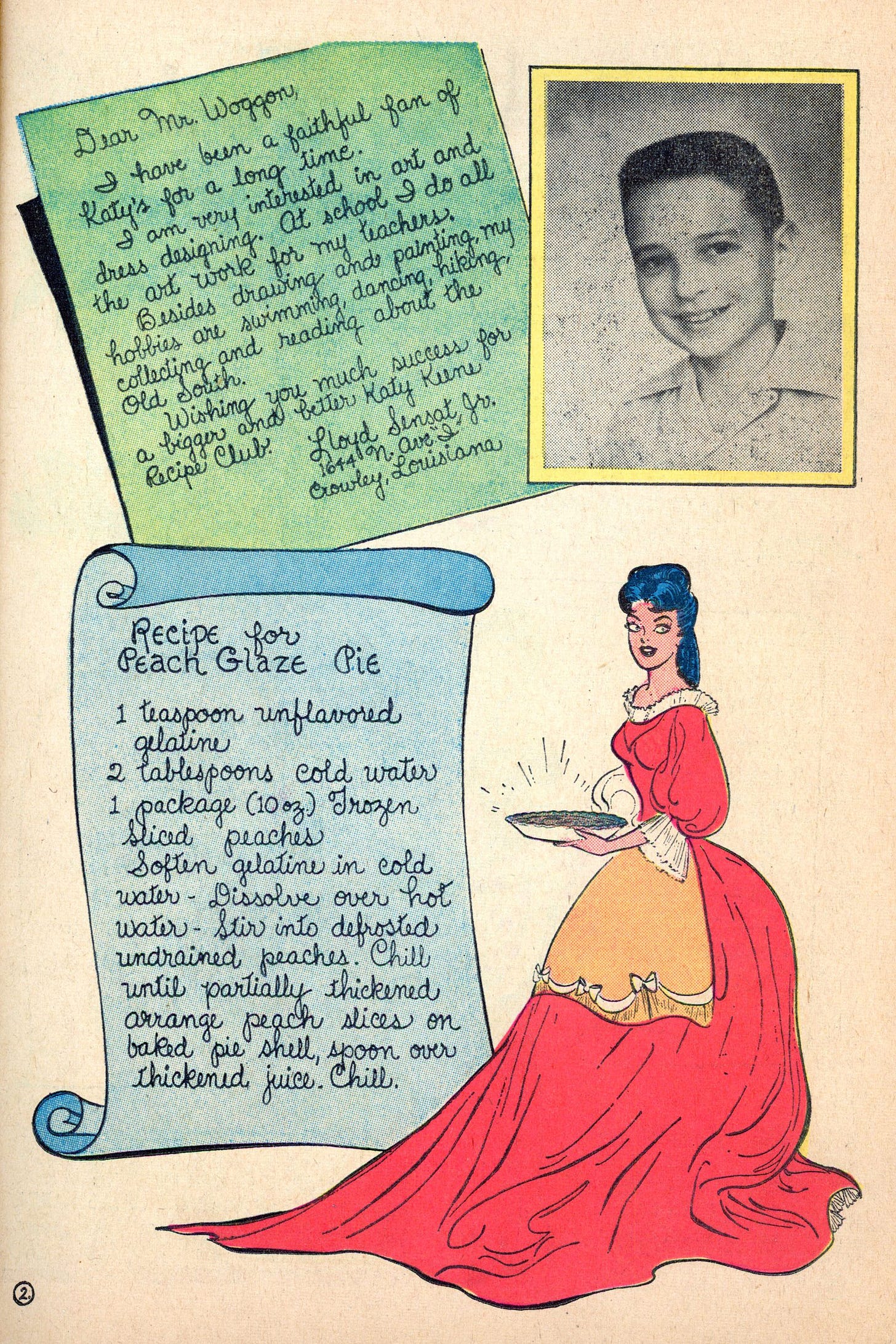

Taking an idea that had been briefly tried out in the syndicated newspaper comic strip Dixie Dugan (a Hollywood showgirl loosely modeled on Louise Brooks), Bill Woggon started call-outs for fan costume ideas in the late 1940s. By the time Katy Keene Comics appeared, fan-generated art was an integral part of the comic’s appeal. During the 1940s and 1950s, he got an average of 1000 to 3000 letters per week and all of them would have a drawing—over time these drawings expanded from only clothing to lettering, cars, homes, poems, and even whole plotlines. “Kids would send in their drawings. He would take the drawing and no matter how good the drawing was, re-draw it but keep it as close as possible to what [the child] wanted to do. [The kids] would see their name and they started fan clubs and pen pals,” said Bill Woggon Jr. Operating with a high level of integrity, Woggons never took credit for the reader's work. Alongside each of Katy’s outfits, the kid’s name and address would be printed—crediting their work, affirming their talent, and providing them a way to connect with other like-minded children. It was a forward-thinking way to make the comic interactive and instill great loyalty. Acting almost like an internet message board, children and teens would write letters to those listed whose work they had the most affinity to—whether it was the appeal of a cowgirl look or a butterfly pin-up, many of these connections turned into lifelong friendships.

Kids would obsessively purchase and check each issue, hoping that one of their ideas would be used. Even for those whose work wasn’t chosen, it proved to be a place of continual inspiration. Though the storylines of Katy’s adventures were generally simplistic and tame, her costumes were anything but. Whether modeling in fashion extravaganzas that required multiple outfit changes from her and her rivals or acting in movies that required her to be a Southern belle or other historical figures, Katy Keene comics were always centered on her ensembles. Woggon crafted the storylines around the drawings submitted—cleverly finding a way to get as many people’s ideas into one issue as possible. Each issue had at least one page of paper dolls—a fan favourite, it is incredibly difficult to find uncut issues of Katy Keene.

Unsurprisingly, many fans and contributors later went into the arts. According to Woggon’s son, “The great part about all of this was that there were half a dozen kids were extremely talented and wise. They came to our house in Santa Barbara and would visit. What we found out is that these kids ended up in careers in the arts, directors of art departments or interior designers. One of the highlights of my dad’s career was the kids that went into art because of his encouragement they got from my father and the comic book. Trina Robbins, John Lucas, [for instance]. Floyd Norman was an African-American kid who lived in Santa Barbara. He was reading the comic book and came to visit my dad. He applied for a job. He started out inking and doing borders. He went on to work for Walt Disney and Hanna Barbera. He was 16 or 17 [when he worked for dad].”

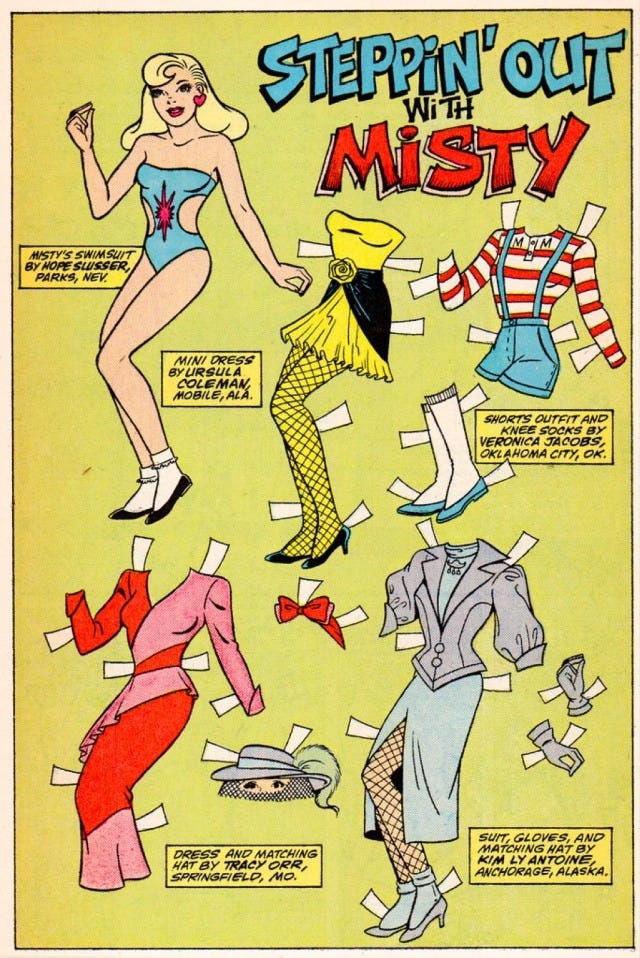

Trina Robbins is a legend in the comics world—she was heavily involved in the underground comix movement and in the 1980s became the first woman to draw Wonder Woman comics—yet it all began with Katy Keene. In an interview, Robbins revealed, “All you have to say to a woman of a certain age are the two words, 'Katy Keene,' to watch her eyes light up. Immediately she'll reply, 'That was the comic with the paper dolls, right? The one where readers sent in designs?' And she'll tell you how she used to design clothes for the comic's glamorous heroine, how she used to cut out the paper dolls, sometimes how it was the only comic book she read as a kid. Bill Woggon hit on a winning formula when he opened his comic to readers, creating a pre-computer age interactive comic book… I was one of those fans back in the 1950s. But, like many other kids, I never realized that Bill redrew the readers' designs for publication. I thought all the fans whose designs were published were little Da Vincis, and, thinking that I could never draw as well as them, I kept my paper dolls to myself. The result was a brown paper grocery bag full of paper dolls that I had designed."2 Trina brought out her own paper doll-heavy comic in the mid-1980s, Misty.

At the height of Katy’s success, each issue sold over a million copies. Unfortunately, Woggon did not own the copyright on any of the work he did for Archie Comics and was only receiving approximately $50 for a completed comic book page during this period. On the evening of April 15th, 1961, Woggon was relaxing at home when he got a phoned telegram from John Goldwater at Archie: "Stop work on Katy Keene immediately, air mail letter will follow." The popularity of comic books for girls had begun to wane and Katy was one of the many canceled. He found some work on other comics before retiring from comics until a sudden resurgence of interest in Katy Keene occurred in the late 1970s (more on that in this weekend’s newsletter).

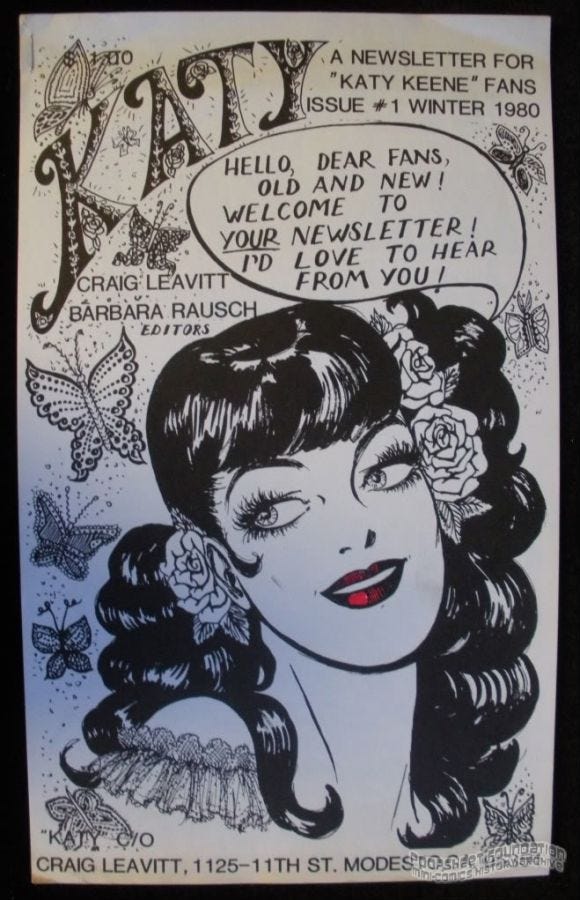

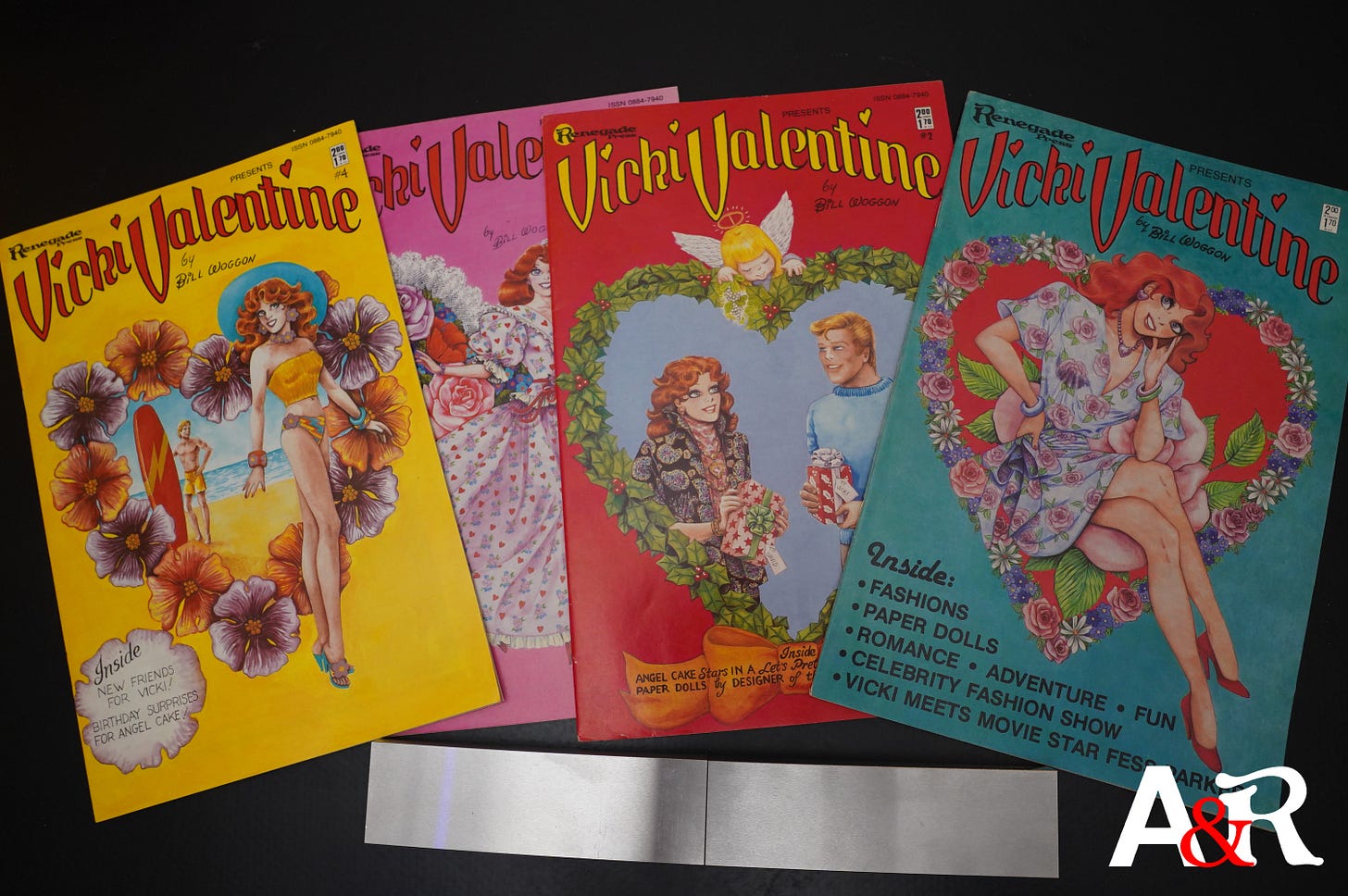

John Lucas, the fan artist mentioned above by Bill’s son, was instrumental in helping a 1980s revival of Katy Keene. Another lifelong fan, Craig Leavitt, began publishing a fanzine in 1979, which published the work of Lucas and other fans-turned-professional artists. With Archie Comics’ permission, the fanzine evolved into Katy Keene Magazine, which ran for 19 issues until 1985. Seeing the popularity of this, Archie Comics brought her back in 1983; her new comic ran as Katy Keen Special from September 1983 to October 1984 (#1–6), and then Katy Keene from December 1984 to January 1990. Katy subsequently reemerged in 2005 and again in 2020, as part of the New Riverdale line of comics. Instead of an aspiring actress, Katy is now an Instagram influencer. Woggon wasn’t personally involved in the various Katy revivals, though his original strips were often reprinted in the 1980s books. In 1985, Woggon and one-time Katy Keene designer of the year winner Barb Rausch created Vicky Valentine for Renegade Comics. First meant to be a one-off, it was expanded to four issues. Featuring paper dolls, romantic storylines, and very eighties clothes, issues of Vicky Valentine are very rare and collectible.

Bill Woggon passed away in 2003 at age 92. Robbins remembered, “Bill himself was a charming and dapper gray-bearded gent, gracious and delighted to be remembered after so many years. Despite the fact that Bill was a regular churchgoer, if he noticed that all the boy fans who'd read his comic were gay, it certainly didn't bother him."3 Katy Keene had an incredible impact on many young boys, including Antonio Lopez and Willi Smith. The fact that her extravagant clothes were designed by other readers provided kids with the impetus to put their visions on paper for the first time—laying the groundwork for fashion careers of their own.

More on Katy Keene, Lopez, and Smith in my next newsletter. All Katy Keene scans from my collection.

Maureen Foley, “KATY KEENE AND BILL WOGGON, STRAIGHT UP.” All quotes from Woggon’s children from this interview.

"Obituary: Bill Woggon 1911-2003,” The Comics Reporter.

Ibid.

Thank you! I loved and still love paper dolls. I collected the Dover Illustrated paper doll books in the 80's, still have them - Shirley Temple, Erte, ballet costumes, movie stars, designers. I think some are still available.