The events of the last week have left me (and most others) heartbroken, grieving, and scared. It’s hard to know how to move forward talking and writing about so-called “frivolous” subjects, yet at the same time, history (all history) and beauty are vital. Last year, when war broke out in Ukraine, I put together several posts that spoke on aspects of war, history, and fashion. The first looked at how historic newsreels capture aspects of culture destroyed by war; as I wrote then, “Beyond the loss of life in war is the loss of culture: the bombings of historic buildings and museums; the destruction of artifacts, art, and crafts; the death of those with knowledge of heritage ways; and the annihilation of cultural meeting places and centers of knowledge. All are victims of war and its aftermath, particularly when a place is conquered by a differing culture.” Among the newsreels I included are several from Palestine. I then wrote about war and oral histories, how Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar ignored the threat of war in the late 1930s, British Vogue’s publisher’s memories of WWII, and the boycotts on German goods undertaken by American and British merchants in response to the actions of Nazi Germany during the 1930s.

In a 1983 issue of Town & Country, I came across an essay by the first American model to work in Paris following the war. Her memories—so distinct, so evocative—bring the reader back to Pierre Balmain’s atelier in 1949, to the Paris Opéra, to the sense of the world reopening and endless possibility.

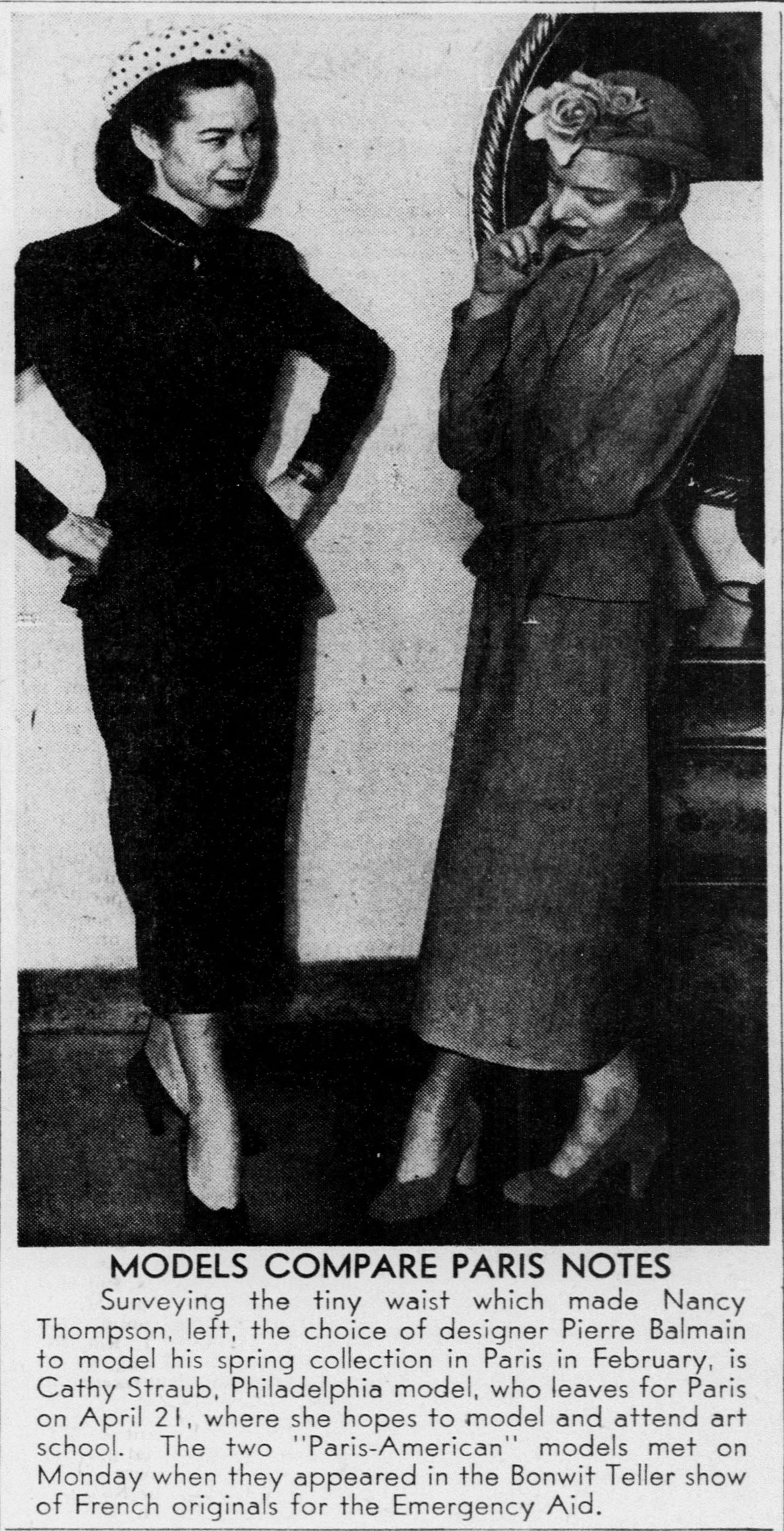

The young American model Nancy Thompson (later Holmes) met Balmain when he came to Washington D.C. in early 1948 to show his collection at Julius Garfinckel & Co., a prominent department store. In the essay below, Holmes writes that his trip was in March 1948, but he visited Garfinckel’s on April 26 as part of a tour of stores initially organized by Boston’s Filene’s to celebrate Air France’s first non-stop flight between Boston and Paris. Balmain and his mannequin Jeanne Gara arrived in Boston on the 20th, sprinting from department store to department store along the Eastern seaboard until Gara, unfortunately, developed a fever—leading Thompson to be brought in as a replacement. As she recalls below, Gara’s illness changed her life forever—bringing her to Paris and a life far beyond her imagination, then a married mom of two living in the suburbs outside D.C.

Nancy Thompson Holmes’ life is so fascinating that I am working on a forthcoming newsletter about it but, for now, here are her memories of Balmain and Paris in 1949.

“Back to Balmain”

Town & Country suppl. ‘The New Romantic Spirit Of The 80s,’ May 1983

By Nancy Holmes

Sitting in Maxim's at lunchtime, you can become convinced that the world hasn't changed. The same thin winter sunshine streams through the tops of the wide windows, the pale light falling on faces you have seen many times before. Isn't that Sadri Khan who just nodded to you? Yes, of course it is. And the gentleman beside you—Erik Mortensen—doesn't look a day older than he did when the three of us sat at this same table together all those years ago, does he? Erik; the man who has now inherited the mantle of Pierre Balmain. Erik—the man whose hand was alongside Balmain's on all the dresses, all the ballgowns, all the robes de mariée through all the years—is saying, "Don't you remember that tailleur, it was yours, with the pencil skirt and the long jacket with loops of jet paillettes here, and here and here?" He sketches rapidly on a scrap of paper as the past tugs at you. We were all so young and so broke then. You sit there, remembering Pierre Balmain, one of the sublime talents in the reawakening of the French couture, with his wonderful hands and those never-to-be-forgotten dresses that brought love into your life. But the world has changed. Reality slugs you. We're rich now, and slightly overfed; Pierre Balmain is gone and Erik Mortensen is picking up the check.

It all started when a French model got the flu in March of 1948, in Washington, D.C. My whole world changed then, forevermore, by virtue of a vicious little virus that felled Pierre Balmain's model and enabled me to be her stand in. What glory! Dear little virus, where would I be without you?

The great couture houses of Paris were on the mend, staggering to their feet again after the war. Slowly but surely, and with passionate American support from stores like Julius Garfinckel & Co. in Washington and Neiman-Marcus in Dallas, the fervent talents of the big three—Jacques Fath, Christian Dior and Pierre Balmain—were bringing French fashion back to life. Miss Elizabeth Fairall, the formidable and brilliant vice-president of Garfinckel's, arranged to bring Balmain, one of his models and part of his new collection to Washington. That alone was innovative for the times. A great young French couturier coming across the seas to show his clothes in little old Washington, D.C.? The mountain had come to Muhammad and the mountain was no fool. Balmain knew that Americans could well afford his clothes, and he wanted to see them for himself and see what their lives looked like. I was the local girl who had made good; Washington-born, John Robert Powers-trained, experienced in New York modeling—and wild about beautiful clothes. Miss Fairall backed and believed completely in Pierre Balmain, and she was wilder about beautiful clothes than even I was. Pierre's model, Jeanne Gara, feverishly abed with the flu, was exactly my size. The clothes that had been made on her fit as if they had been made on me. I had fallen into a tub of Balmain butter.

Pierre Balmain was a solidly built, handsome man with a sort of Rock-of-Gibraltar elegance. He had a strong head and a magnetic look in his warm brown eyes. His impact was so definable that one eminent chronicler of the doings of the elegants said of him, "It made no difference what room he was in, he was always `quelqu'un.'" From the moment I first met him I adored him. I knew I was with a master, and I would have walked the plank for him.

And for his clothes! The first Balmain dress I put on was a dinner dress with a layered navy blue chiffon skirt and a perfectly constructed, pristine white linen jacket that was nipped in at the waist and embroidered around the neckline and short sleeves with small turquoise and crystal flowers. It was deceptively simple and simply delicious, and for the first time in my life I knew and cared that I looked exactly right. The dress felt different than anything else I had ever put on my back, and it was. It was Balmain couture and I was a goner. There was no going back, and I never did.

In the short time that he was in Washington our friendship formed. Fortunately for all, he liked the way I wore his clothes, and he respected Miss Fairall, and he was no dummy. "Why don't you let Nancy come to Paris and pass the next collection for me?" he asked. "What a splendid idea, an excellent idea!" Miss Fairall said. "For Garfinckel's and for you, too, Pierre." "And for me," I screamed silently to myself. To be the first American model in Paris after the war and to belong to the house of Pierre Balmain? I immediately started getting neurotic about catching the flu.

I arrived in Paris on a clear winter's morning after thirteen excited, sleepless hours on Pan Am's Constellation flight. Pierre was there to meet me, and so was Erik Mortensen, the young Dane who was his assistant. So were several of his models—Monique and Carroll and a delicious girl called Praline. No Jeanne Gara. I didn't care. We went into Paris and went to Le Grand Véfour for lunch. It all seemed so civilized and calm. It was the last nonchaotic moment for the following three weeks. Little did I know and lots did I learn.

Paris in January of 1949 was an astonishing place, going through an astonishing time. There was no money, or at least there didn't seem to be any money. There were beautiful silks and satins and wools, and there were long branched white lilacs and fat pink French roses on the tables at Grand Véfour and Taillevent, but no money changed hands. Over the finest glass of the finest champagne, all of Paris was singing, humming, whistling or fiddling "La Vie En Rose," along with Piaf, France's famous sparrow, but there wasn't any money. The currency that was used by Balmain to pay my hotel bill was a dress a week for the owner's wife. There seemed to be a barter system for everything. Betty Dodero, the beautiful young wife of an Argentine millionaire, adored Balmain, and she was ordering masses of everything from a preview of the collection. It would be weeks, even months, before the clothes were ready—and billed. Balmain showed her one of the newest mink coats, the first gray one made. The color was called Silver Blu. Madame Dodero bought it on the spot. "Cash?" Balmain asked, a rare question from him. "Of course, if you like," she answered, peeling off bills. It covered everything for the house of Balmain for several weeks. There was money.

While the collection was being completed, I stood, being fitted with twenty-four outfits, for ten to twelve hours a day. A silk thread was tied around my waist. "What's this for?" I balked like a Missouri mule. "It's digging into me." "You can cut it off at night but it reminds you to hold in and stand up," I was told. It reminded me of a twelfth-century Spanish torture, but there it was. At about eight in the evening, Pierre would look at me as if he hadn't made designs on my pale white body all day long, and gently toss me something to wear. I didn't realize it at the time, but he had scored a coup. I was the only American model in Paris and we went everywhere there was to go. "She is my star," Balmain would say. "She stands for twelve hours a day and dances for the next twelve." It was heady stuff, made headier by the beauty of the clothes being made on me.

The collection opened, to great excitement and an even greater reception. The cabine where the models dressed was a high-ceilinged room about the size of a small living room, and it was a madhouse. Nine models, four dressers, two jewelers, two fur men, a milliner and two neurotic dogs inhabited it, and here I ran into trouble. Every outfit was complete down to the tiniest detail, and several of the tiniest details seemed to be missing from my collection, always at the last minute. A belt, a shoe, a scarf; nothing of value but something vital to the ensemble. I was late getting to the runway. Most ensembles had names. Balmain would call out, "Numero Trente. Mon Favori." Mon Favori was mine, a lavender tweed suit with a tiny lavender and white striped blouse and an off-the-face white felt hat to wear to the races at Longchamps or Chantilly. When he called, there was an uncomfortable silence and no me. After the third time, he came back into the cabine and glared at me. "Why is it that only the American model is not on time?" I burst into tears. Praline, his most fabulous model, who sat on one side of me suddenly saw a smug little expression on the face of Jeanne Gara, who sat on the other side of me, and realized what was happening. Gara, jealous, was hiding my things. Praline whispered in Balmain's ear, and his smile reappeared. He loved intrigue. Once the show was over, he took Gara aside and confided to her that since I obviously could not get myself together he was appointing her to take the responsibility of getting me out on the runway on time. Gara knew that she was not only found out; she was trapped. At the next showing, my darling friends Praline and Monique not only nicked from me, they also hid a few of Gara's things. She was frantic, and late. Balmain came back and scolded. "Not only the American?" he said, glaring at her. Nothing else was said. We had no more of that sort of trouble.

Paris was still licking the wounds left from the years of collaborationists, which brought about one of the most spectacular evenings we spent together. Serge Lifar was going to dance at the Paris Opéra for the first time since the war. No one knew how he would be received, as the collaborationist label was on him. But it was an occasion, a happening—and it was quickly apparent that everyone was going to be there. Pierre had sensed the importance of the night, and we were going. After the show, he looked at me with that cool expression I'd come to know so well. I had given myself over to being entirely unselfconscious and to wondering if I would ever be able to put myself together again without him. I watched him. His lump of clay was ready, and the silk thread around my waist was not cutting for once, an encouraging sign.

"Yes," he said and walked out of the dressing room, returning a few moments later with a dress I had never seen before. Oh God, I thought, my own are enough for me to "carry" in this wild new world of elegance and proper dressing. Now what? The dress was a slender shaft of strapless black velvet, the bosom draped in black point d'esprit, with layers of the soufflé-light point d'esprit flickering out from knees to floor. It fit perfectly except for being so tight at the knees that I could just barely mince, like a Japanese doll, rather than walk. Pierre looked at me again, said "Yes" again, and left the dressing room again. This time when he returned he gave me something made of moon-colored jersey, encrusted with crystals and pearls. It was more than a cap but less than a turban and it covered all of my hair. Soot-black pumps and above-the-elbow white gloves appeared. He gave me the long cool look again. A lush black fox boa appeared and was wrapped around my right arm. "Ah, yes," he said, and I knew I was ready. The dress was so tight at the knees that I don't know how I got down the stairs or into the car, but suddenly we had arrived at the Opéra and every light in Paris was on and everyone was there, looking hungrily at everyone else. Pierre and I made our promenade, along with the others, flirting shamelessly with each other, so we could see and be seen. My foxless arm clung to him for dear life, half from exhaustion, the other half excitement, as every eye was on us. When the time came to go up the great marble staircase and take our seats, I tried to take the first step and the dress said "NO." It meant it. It was impossible to maneuver my knees in any way to take the first step, or any of the others. "What's the matter?" Pierre whispered lovingly in my crystal-and-pearl-covered ear. "It won't move," I said adoringly, panic setting in. Pierre understood instantly. "Turn around," he hissed sweetly. "We shall continue to promenade." When all were in their seats and no one was watching, Pierre started to laugh, wiping his eyes with his handkerchief. "What are we going to do?" I asked, feeling terribly insufficient and non-Parisienne. Pierre looked at me as if the war were still on. "Ready?" he asked, swept me up into his arms as if I had been a sack of flour and rushed up the long staircase with me. I started to laugh, grabbing for the cap, which was falling off, and trying to keep the boa from trailing on the staircase. He put me down, a victorious smile. on his face, and said, "I know you can walk down, you did from the house to the car. We'll do the same thing again after the intermission." He adjusted the heavily encrusted cap and we went, fashionably late, to our box. Lifar was a huge success and so were we, and Pierre was pleased. I never saw the dress again, and it was the only one I wore not from my own collection. Years later, I asked him about it. "It was perfect for that night," he said. "It was one I had especially designed for Evita Peron; she would have killed me if she'd known that anyone else wore it."

Pierre's elegant, romantic heart translated into everything he ever made. He adored women and their curves, and he was as famous for never making anything flat-bosomed as he was for the myriad number of weddings that he did. It became almost instantaneous tradition for Balmain to do the most important weddings, and steadily for royalty. One of the last great ones was in 1981 on Valentine's Day for Crown Prince Henri of Luxembourg and his beautiful Princess, Maria-Teresa de Mestre. Her dress was ivory satin edged with white mink, the Belgian lace family heirloom veil held in place by a diamond tiara. Members of the royal families of ten countries were there, more than half of whom had been gowned by Pierre Balmain for their own weddings.

Weddings were not his only spectacular contribution to the art of being beautifully turned out. The Balmain perfumes are legendary. As the setting for the introduction of Ivoire, the newest perfume, Balmain and Jacques Bergerac, president of Balmain perfumes, chose the banks of the Nile and the shadows of the Pyramids. Under the sponsorship of President and Mrs. Anwar al-Sadat, the world came to meet Ivoire. Frank Sinatra sang. The titled, monied internationals danced beneath an Egyptian moon at a party no one has forgotten. Ivory tones had figured prominently in Balmain's thinking for many years as a sort of ne plus ultra of elegance. Jacques Bergerac tells the romantic story: "It was always a dream of his, this cool, slender beauty, dressed in pale tones, lavished with pearls... she was always appearing to him, in Aix-les-Bains or Lake Como, even at the Paris Opéra."

She could have been almost anyone, this mythical inspiration for his perfume. He dressed everyone, and was known as the "Dressmaker of Queens." He created, officially, everything that the exquisite Sirikit, Queen of Thailand, wore on her stately visits around the world. Empress Nagako of Japan bestowed the same honor on him, and so did Fabiola, the Queen of Belgium. Princesses, duchesses, countesses—they flocked to Balmain. He had from the beginning the reputation of being the most expensive and classic of the couturiers. Ginette Spanier, his directress, who now lives in London, says, "I walked in one day and didn't leave for twenty-nine years." His taste was something I will never get over. Erik sent me a dress recently; to have something that is made in the Balmain way is to still have luxury in an ugly world." Hebe Dorsey, Paris' cloutiest columnist, was devoted to him. "All of us knew that Balmain never made news," she said. "But what always did make news was his ten- or even twenty-year-old dress that stole the party. He couldn't help his romanticism, his elegance."

There was more to it than that. Balmain was a master at making sexy ladies look elegant and elegant ladies look sexy, from Katharine Hepburn to Catherine Deneuve. Young, but never vulgar, was his theme, and Erik Mortensen intends to continue along the same line. The world is strewn with ladies whose Balmains are as protected as their jewels, who can't bear to let a Balmain—or the memories that go with it—go. Both are too special. So are the perfumes, from Vent Vert to Jolie Madame, all of them, especially Ivoire. That alluring lady is still there, in the scent, and the amazing thing about it is that it sells, one of the world's most expensive perfumes, to the shop girl as well as to the monied lady. They save up to buy it. They must know something. He certainly did.

And so do I. He taught me everything. Polyester has never crossed my path. One night in Carrère—the sensuous, small boîte de nuit that was the rage at that time—I rose from the banquette, wearing a dress he called "Pousse Café." A black silk jersey blouse topped seven skirts, short, the top one made of black Chantilly lace, the rest in tulle all the colors of the rainbow, creating the effect of a pousse-café. The silk thread around my waist was almost as tight as the wide patent leather belt. "Where are you going?" he said. "To the powder room." "NO!" he said. "Sit down, the maids in there are paid to sketch the clothes from the new collection. You can't." My glass was filled once more with champagne. I tipped it to him. "I'd give up anything for you," I said. He was worth it.

I want to see these dresses!

What an absolutely fascinating story! Thank you.