For the past two weeks I’ve barely been going on Instagram—the parade of tone-deaf photos from Milan fashion week (and now Paris) difficult to stomach in a time of war. I understand the importance of continuing with the shows (roughly 430 million people worldwide work in the fashion and textile industries) but, as many others have pointed out, condemnations and actions from fashion brands and personalities have come at a glacial pace. While the effects WWII had on the fashion industries in Paris, London, and New York are well-known—or more specifically, the effects once those countries were shelled, invaded, or entered the war—what of the years before? If, as some experts say, Putin’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 is analogous to Hitler’s March 1938 annexation of Austria, then where are we now and where are we headed?

I set out to write about how the fashion industry reacted to the prospect of WWII, but that is too giant and unwieldy a subject for a single newsletter. Instead, I am going to focus on how American Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar both alluded to and ignored the situation in Europe and the threat of war.

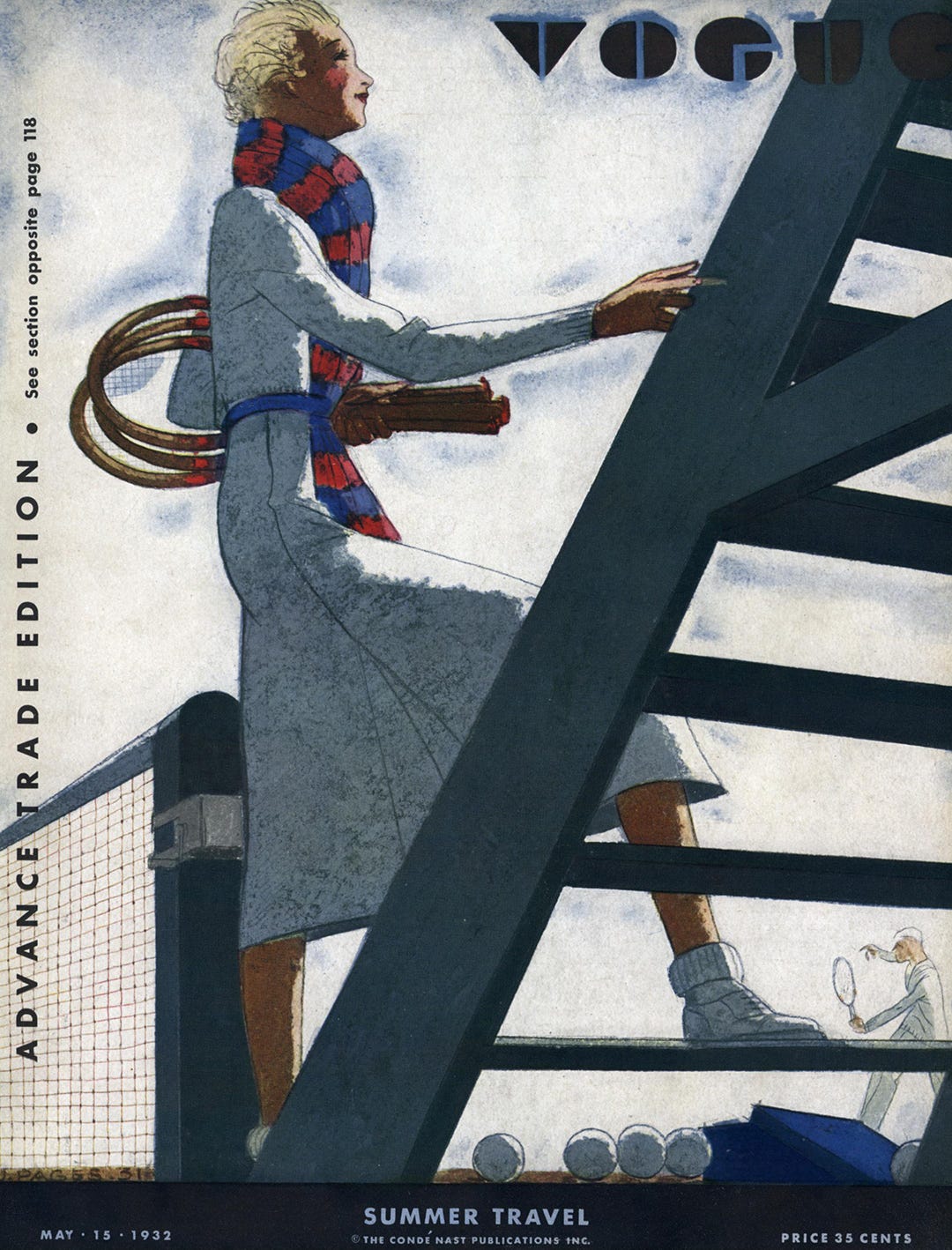

The first real mention of Hitler in Vogue came in May 1932. Head of the Nazi party but not yet chancellor, Hitler is briefly discussed in a travel article about Berlin written by Vogue’s anonymous “As seen by him” society columnist: “Is that Hitler that little man I see? No one could be more commonplace or, I feel, at sight, more antipathetic. Yes, it’s Hitler, all right, and he has started to talk. But I think he speaks very badly; he has not a cultivated voice, like the man who has just spoken; and he becomes increasingly antipathetic to me. Why, I ask, is there all this fuss about Hitler? I am told he represents an idea, and, because of that, he has become a sort of god to many people.” Thus begins the common theme throughout mentions of Hitler in the major magazines in the thirties—as a “little man” who can be laughed at and not taken seriously by high society, to be only discussed in passing in gossipy travel pieces or in his uniforms relation to fashion.

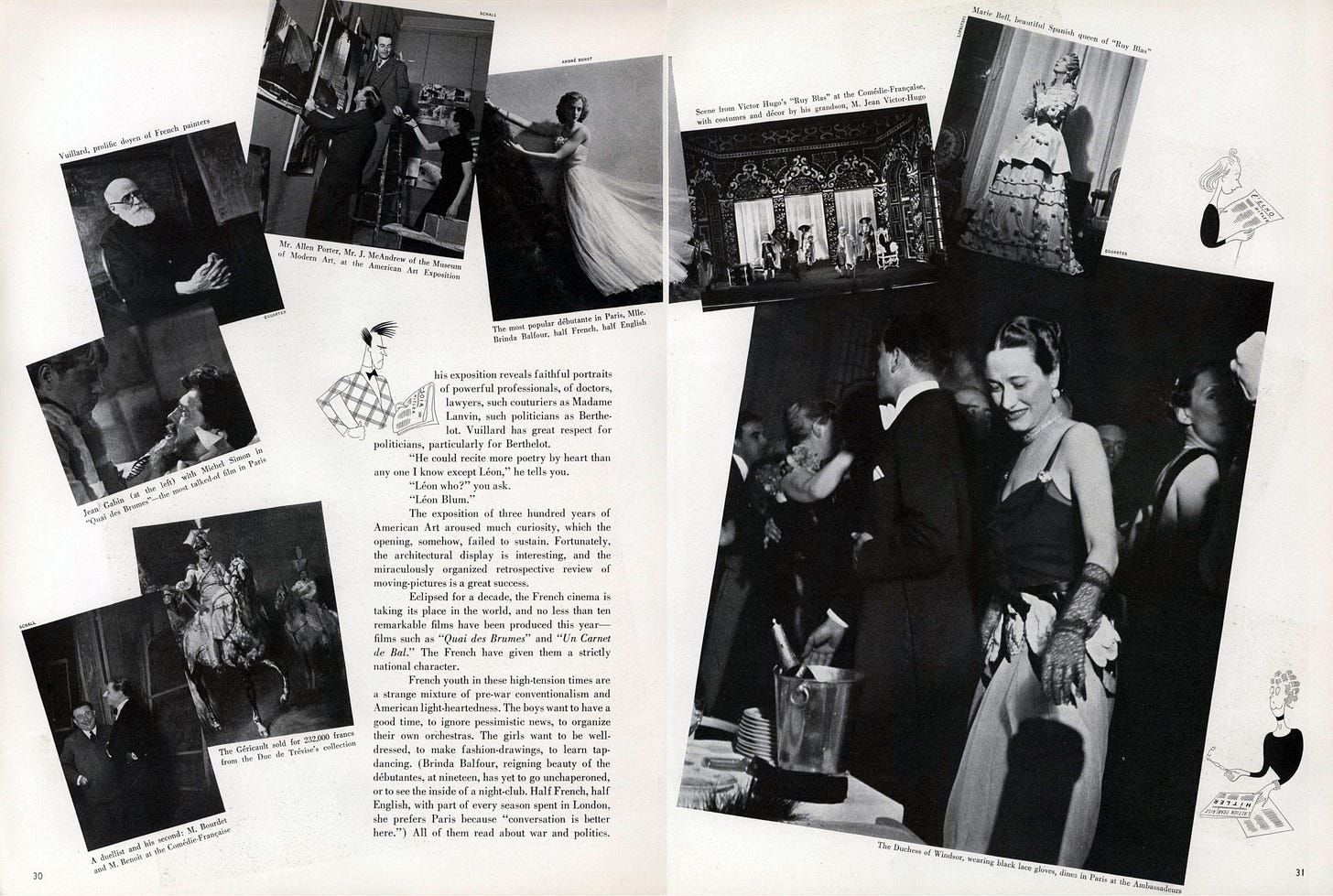

It’s important to note here that Hitler was sworn in as chancellor in January 1933; within two months there was a widespread boycott of German goods by American, British, and French stores due to the Nazi regime’s attacks on Jewish businesses. These boycotts were widely reported in trade publications throughout the rest of the decade but never mentioned—even in passing—by the fashion magazines. May 1933 and Harper’s Bazaar is busy describing the new colors in women’s blouses as “Fascist black ones, and Hitler brown ones…” while in September 1936 Vogue seems positively overcome with admiration for the Nazi aesthetic: “[Munich] looks very chic—what with half the men in uniform (some of Hitler’s uniforms are beautiful in color: light greyish green with dark grayish green, warm burnt-toast with black, black with red)… The general impression is that every one in Munich is young—it must be due to all the healthy pink cheeks and energy and enthusiasm. Companies of young Nazis in uniform sing as they swing through the streets… Americans overrun the town because, with the tourist marks, everything is ridiculously cheap… And certainly the reception that the Nazis give the foreigners is enthusiastic.” Months after the Nazis reoccupied the demilitarized zone in the Rhineland in violation of the Versailles Treaty, Diana Vreeland (in her acclaimed “Why Don’t You” column for Harper’s Bazaar) recommended dressing in “bare knees and long white knitted socks, as Unity Mitford does when she takes tea with Hitler.” Vogue even published a look at the interiors of Hitler and Mussolini’s homes in their August 15, 1936 issue. There is no sense of danger in the references to Hitler or Mussolini—at most annoyance at how talk of them saturates cocktail party conversation.

On 12 March 1938, Hitler announced the unification of Austria with Nazi Germany in the Anschluss; this annexation was mentioned once, in an article by the food writer M. F. K. Fisher for Harper’s Bazaar. Published in the December 1938 issue, she talks of learning about the Anschluss while in Switzerland. Speaking with a hotel concierge, he tells her, “This is war. Automatically. This time is war.” This concept—of an imminent war—is only hinted at one other time in 1938, in either magazine; Vogue’s “People are talking about” column for April 15, 1938, leads with “War around the corner, with people quoting Dorothy Thompson, who has stayed mad at intolerance more consistently than most of us…” followed directly by “The new Elbow Room Club, which is pretty private…” and “The ballet this summer in Paris…”—a clear example of with what little seriousness these magazines took the prospect of war. Following the Munich Agreement on September 30—which gave Hitler the Sudetenland part of Czechoslovakia in a failed attempt at appeasement—Harper’s Bazaar wrote, “Now that the war scare is over, there will be bright lights instead of black-outs. More music than we have had in ages and surprises breaking from eight-forty until far into the night… And if you tune in on the radio, you’ll get Toscanini instead of the Voice of Doom.” Over this same period, Women’s Wear Daily and other trade publications documented the Nazi takeovers of Austrian Jewish stores and businesses and the boycotts of Austrian and Czech goods that followed; again, these are never mentioned by Vogue or Harper’s.

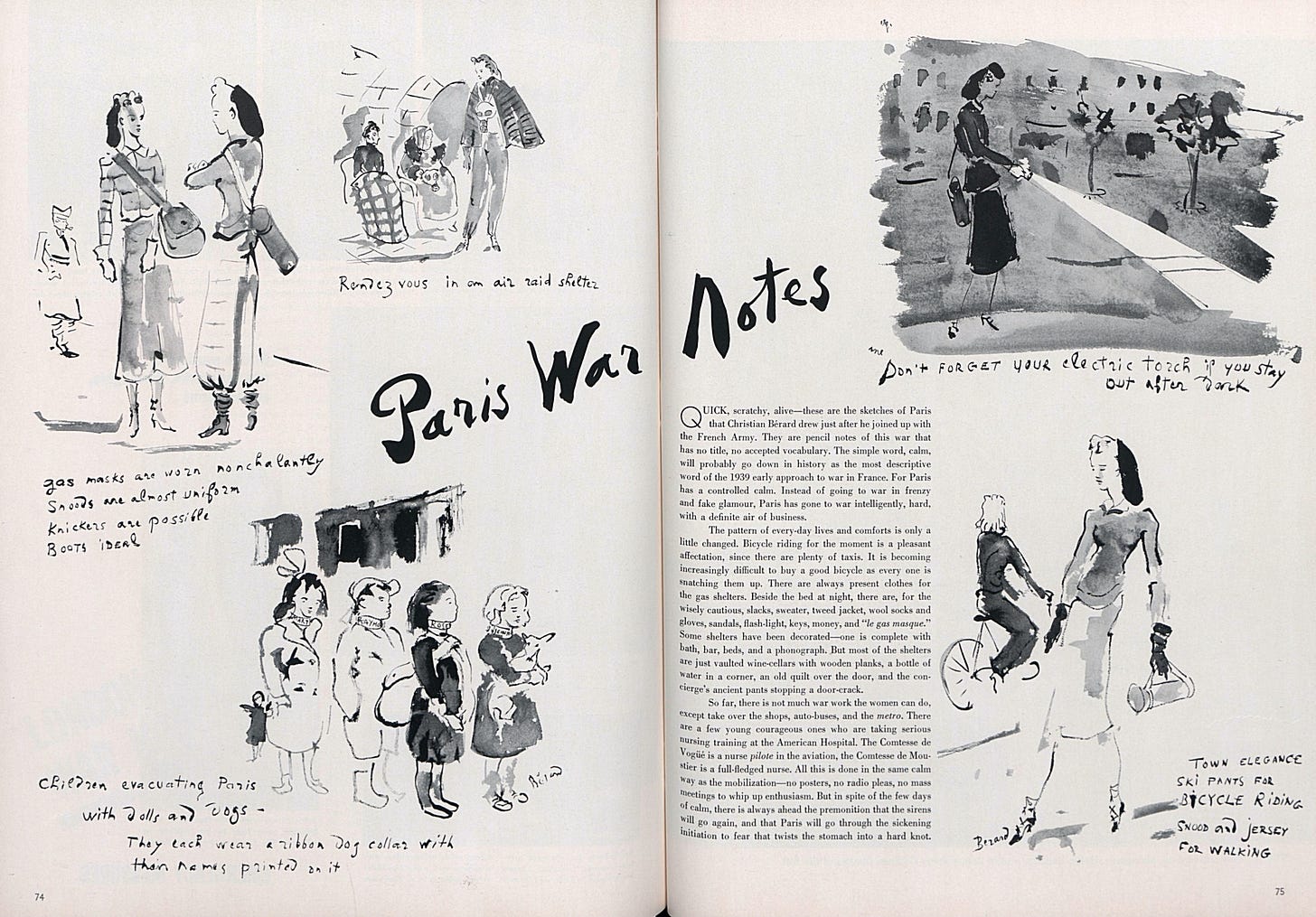

With Europe in a state of anxious peace through most of 1939—Hitler busy plotting and the French and British governments attempting to prepare their militaries and defenses—fashion continued on. In a June 15, 1939 feature on “New fashions, pleasures, and politics in Paris to-day,” Vogue paired photographs of magnificent ruffled Vionnet dresses with a discussion of gas masks. The fall collections—all slim suits for day and escapist, Belle Époque inspired gowns for evening—had been shown in Paris in August; as Vogue relayed, “Created in the atmosphere of impending war, carried out as the atmosphere grew darker, they were shipped out of France and arrived here just before the outbreak of war.” After the shows, Harper’s Bazaar editor-in-chief Carmel Snow went around the couture houses to say her goodbyes and found evacuation already in process; writing a letter on August 28th (later published in the October issue), she describes finding out how one-by-one designers (like Lelong), managing directors (like Trouyet at Vionnet), and artists (including Christian Bérard) had been mobilized while others, like photographer Erwin Blumenfeld, had volunteered. On September 1, Germany invaded Poland; two days later France and Britain declared war on Germany, thus beginning the eight-month “Phoney War.”

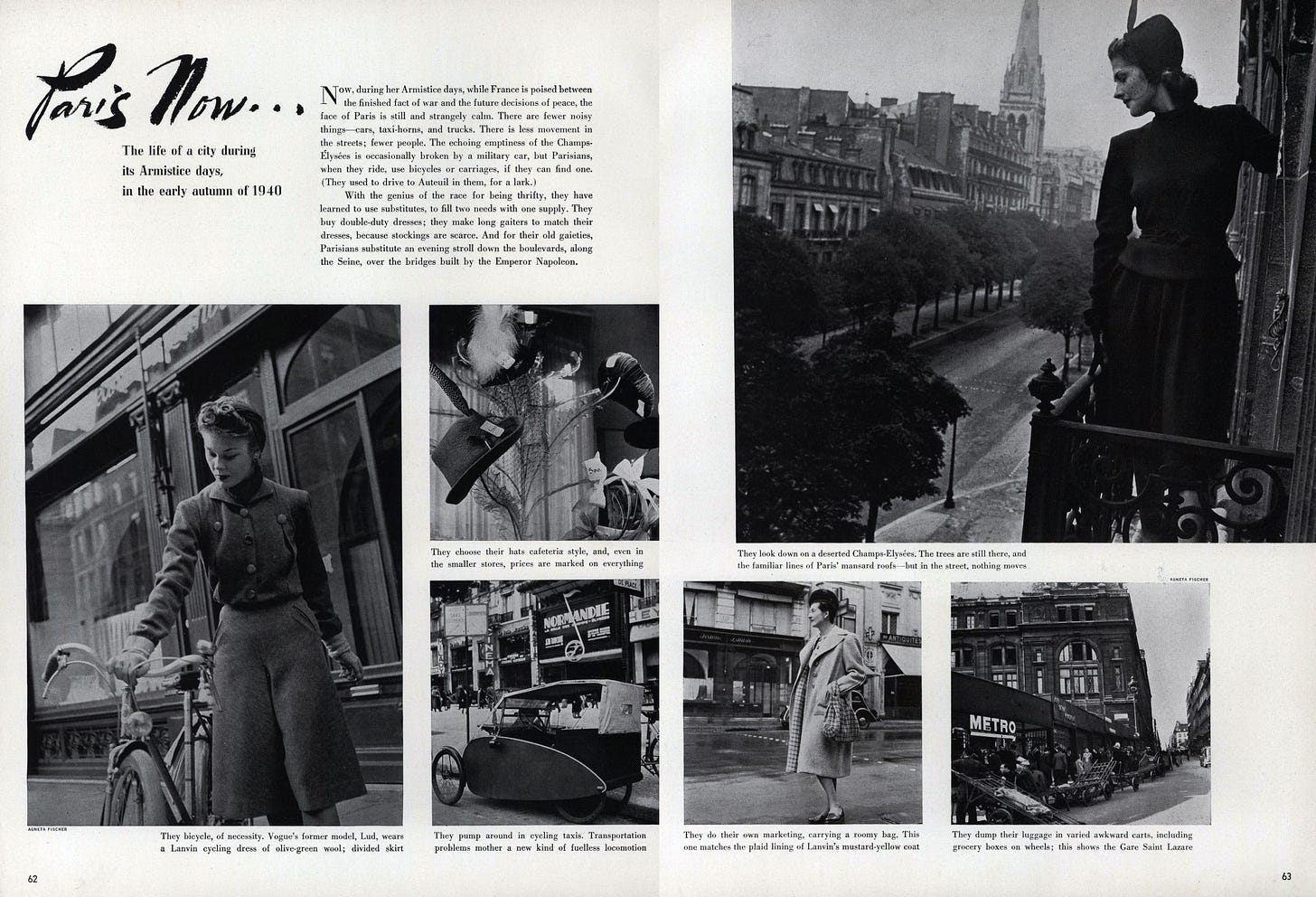

With Paris and London now on edge, waiting to be attacked, the tone in the magazines began to change. From viewing Hitler as a “little man” to be amused by, the fashion magazines were now focused on regaling their readers in America with emerging trends among fashionable women and socialites in these newly at-war places. Vogue’s “People are talking about” was now exclusively war-focused: “The effect of the War on the theatre, clothes, the opera, and the new corset. The feeling of uncertainty, of living in a tightened-up world, as though we were being squeezed by a giant nutcracker.” A letter from Harper’s Bazaar’s London editor documented all the fashions that had emerged for air-raids (zip-up “Siren suits”), blackouts (white raincoats and umbrellas), and sudden weddings, while also describing how Molyneux showed his collection with matching gas mask bags. In November, Vogue published Bérard’s last sketches before going off to training—quickly capturing the new, war-ready silhouettes that were appearing on the streets of Paris; the following month came Eric’s illustrations of the Ritz’s air-raid shelter and Schiaparelli’s new bicycle bloomers.

What’s striking is that there is never any mention of boycotting German goods or any outright declaration against the actions of Hitler or Mussolini. With the center of fashion at war (though not actively fighting), the magazines focused their attention on uplifting and reinforcing the supremacy of French fashion in 1939 and early 1940. The editors still traveled to Paris for the collections in January 1940, writing, “The world of fashion needs the stimulus of French creative talent just as the French workaday world needs normal employment.” It is not until July 1940—after France had already fallen—that Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue published lists of things that Americans could do to help. With France occupied by Germany and Britain under constant bombardment from September 1940 to May 1941, thus began the most-known aspects of wartime fashion—couture under the occupation and rationing. The United States entered the war in December 1941, after which Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar took on a completely new, patriotic tone.

There are many similarities between the current situation and 1938-39, but also as many differences—a key distinction being the ability of social media and the internet to spread information (and disinformation) in an instant. Where magazines and brands in the 1930s could be forgiven a slow reaction and lack of knowledge, the same could not be said today—any delay in action can be seen as betraying certain political views and/or a desire to keep open all income streams. Using social media, magazines (like American Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue) have overall shown a quicker response to the conflict than most major fashion brands—though there is a definite incongruity to feeds of fashion shows mixed with photographs of refugees. It is not an easy balance to find and one I have personally struggled with. Vogue Russia (started in 1998) called for peace on their platforms yet turned off all comments; though it is owned by Condé Nast, it still operates under Russian law—as Putin recently outlawed “any public opposition to or independent news reporting about the war against Ukraine,” that might be why they have returned to posting only fashion shows over the past three days. Vogue Ukraine has been, quite obviously, the most vocal of all major magazines against the invasion.

This article isn’t an attempt to do a direct then-to-today comparison. For one, it’s important to remember that Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar in the 1930s were existing in the shadow of WWI—there was an assumption that no one could want war on that scale again and that the Treaty of Versailles had brought lasting peace to the world. One 1936 essay in Vogue even went as far as to say, “But Hitler or no, there can’t be another world war!” Today we have two World Wars and the Cold War behind us, more distant yet still omnipresent—marking our decisions (and those of politicians, editors, and CEOs) not through memory but through myth. What the analysis above can do is reveal the fault in believing that peace is assured and the perils in believing a leader too silly to be dangerous, as well as the shortsightedness of only looking to one social stratum for information. Perhaps if Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar had paid more attention to Hitler’s actions against the Jewish fashion and garment industries in Germany and Austria, they would have been better prepared for the eventualities of war.

Are you interested in learning more about the 1930s boycotts of German products? Wartime fashion in London, Paris or New York? Let me know if there is any aspect of what I touched on here that you would like me to expand on.