Leading on from my discussion of how American Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar wrote about Hitler and the threat of war in the 1930s, I thought I would share a firsthand account of how British Vogue dealt with and survived WWII. During the war, H.W. Yoxall was the managing director of Condé Nast and publisher of British Vogue. In 1966 he published a memoir, A Fashion of Life, from which the below passages are taken.

For a little backstory on Yoxall: Harry Waldo Yoxall was born in Nottingham in 1896; his father was a schoolmaster, president of the National Union of Teachers, and an MP. Fresh from fighting in WWI—where he survived the Battle of the Somme, one of the deadliest battles in human history—Yoxall returned to Britain from teaching trench mortars in Ohio with the British Military Mission to the United States. With a young American wife in tow, he began his studies at Balliol College (part of Oxford University) but found the Classics and academia insufferable after the excitement and openness of the war and America. After one year they moved back to the United States in 1919, where he began working in the foreign advertising department of a Detroit company. Yoxall joined Condé Nast Publications in 1921, as part of the promotions department. Three years later Condé Nast cabled him from London, requesting that he take charge of the ailing British Vogue (launched in 1916). Moving to London, he became publisher; ten years later he was appointed managing director of Condé Nast, before later being Chairman from 1957 to 1964. He passed away a month before his 98th birthday in 1994.

Truly an overview of the actions of his life—as a soldier, as a publisher—there is little of the personal to this memoir; he even writes, “I don’t like autobiographies that reveal the intimate joys of their authors’ marriages, or discuss what Balzac calls the petites misères de la vie conjugale. Let me simply state, then, that I have been married for nearly fifty years, to the same wife: that we have two children and three grandchildren: and hereafter only refer to this subject incidentally.” For the lack of personal reflections, Yoxall instead shares the intricacies of running a magazine for forty years. While not one of my “must-read” fashion books, I do think that this autobiography is incredibly useful for understanding the fashion and publishing industries during that period.

Not written in strictly chronological order, these reminiscences of the war are taken from throughout the book. They help provide an understanding of some of the adaptations and changes that had to be taken by the fashion industry during those years.

ON TRADE PUBLICATIONS

When the war came, our export effort was next in importance to the war itself. British wool textiles has a world-wide reputation, but except for tailor-mades and cashmere sweaters our fashions commanded no international respect. However, the Government now wanted us to export models as well as yardage, and silks and cottons as well.

I started a quarterly called Vogue’s Book of British Exports, the first trade publication that we had ever issued. This was sent to all the important store buyers of the world, showing not only our fashions and fabrics, but also other fine British merchandise in leather, china and silver. It was a considerable initial success. Suddenly, however, we were asked by the Government to discontinue it. Washington had embarked on its generous Lease-Lend programme, and less generously insisted, as a quid pro quo, that specific British export publicity should be discontinued.

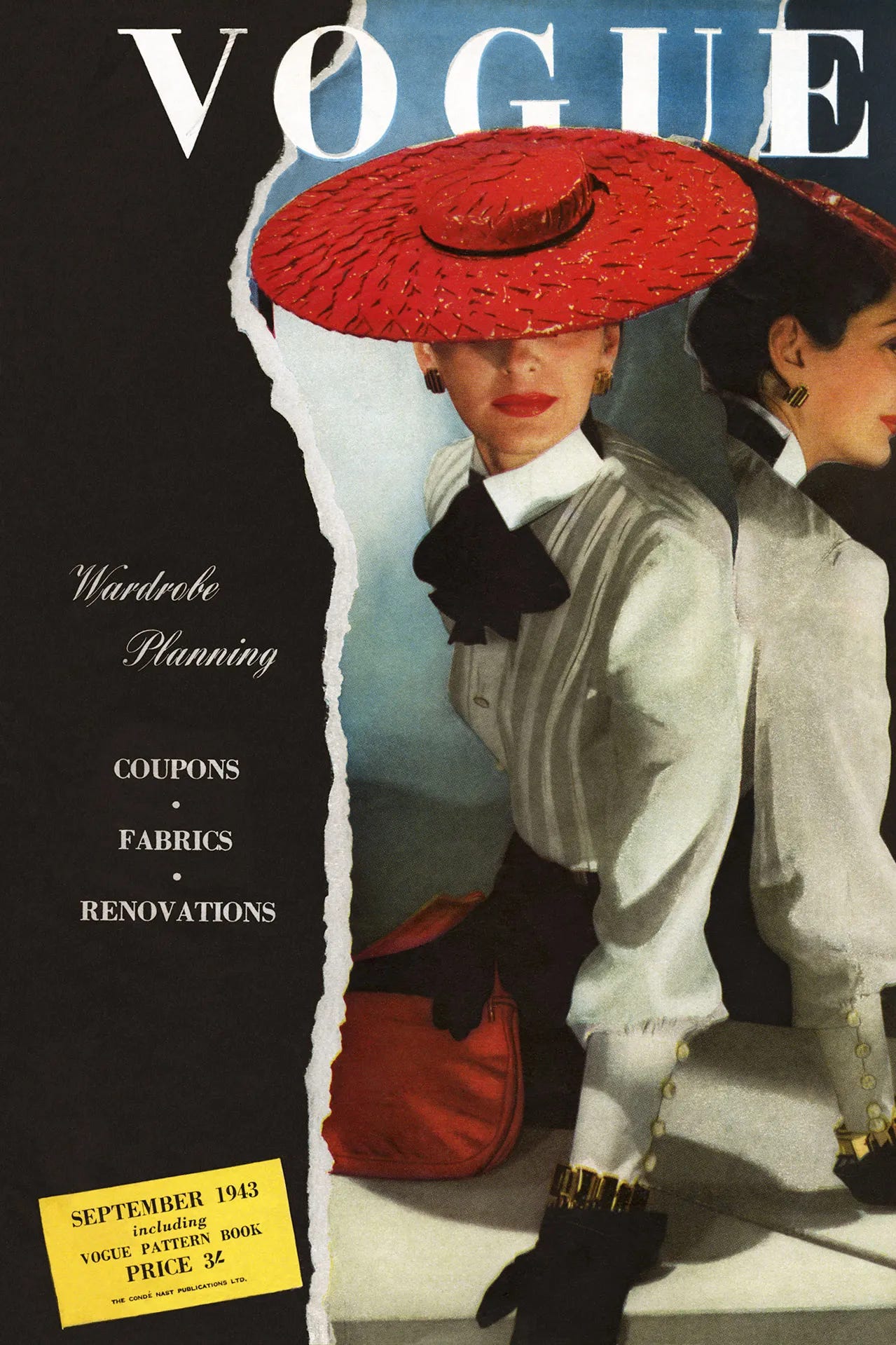

This was a painful blow to us. British Vogue was suffering severely from paper rationing. (At one time we were restricted to a quarter of our pre-war consumption of paper.) But special allocations had been made for export publications, and the advertising revenue from Vogue’s Book of British Exports compensated us for the initial wartime reduction of advertising in Vogue itself…

Later, too, the American attitude became more reasonable – or the British attitude firmer – and we were able to restart our Book of Exports. It continued successfully until further developments in our commercial policies rendered its functions unnecessary; but meanwhile it had given birth to three ‘consumer’ editions of Vogue in the Commonwealth – Vogue Australia, Vogue New Zealand and Vogue South Africa.

ON BRITISH FASHION

Throughout the early war period the small British couture grew in importance, if not in scale. Its need was felt, as a peg on which to hang our export of textiles. Various export efforts were attempted in North and South America, and American Vogue co-operated altruistically in introducing our designs to its great market.

Meanwhile France fell, and suddenly Molyneux, Charles Creed, Madame Mosca and Angele Delanghe found themselves refugees in London. I invited them, and the leading British designers, including Madame Champcommunal of the London house of Worth ( a previous Vogue editor, by the way), to a cocktail party at the Berkeley. I wanted to see if they could be persuaded to work together, and I planned to introduce them to the few American buyers who were still venturing to stay in London…

Out of this meeting grew the Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers… But at first, under the unchallengeable leadership of Molyneux, and with the supremely elegant Hon. Mrs Reginald Fellows as president, it achieved a certain cohesion. Financial support was granted, if only on a rather niggardly scale, by some groups of fabric manufacturers, and special facilities were provided by the Government. While the French couture was closed, or selling perforce only to the Central Powers, the British Society became a moderately effective force in the free markets…

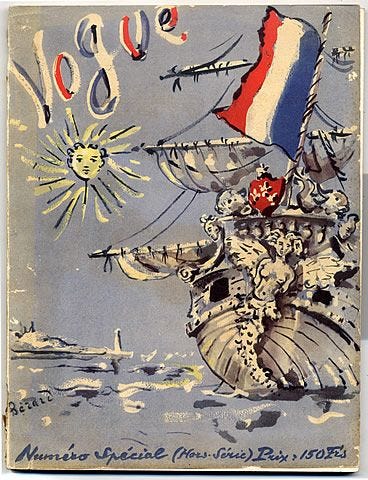

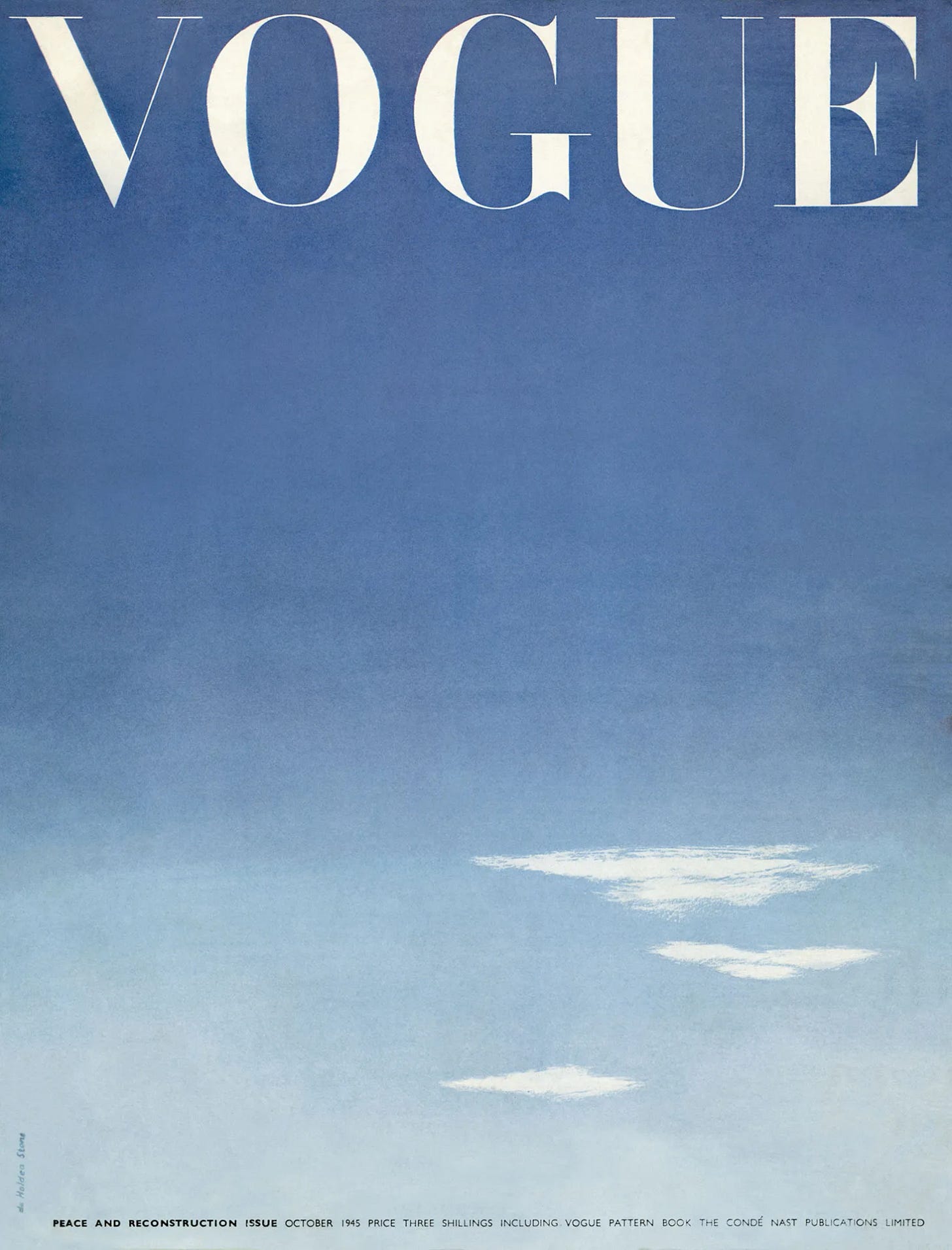

When Paris did not exist, London, for a few years, provided a small, acceptable alternative. But in 1945 Paris came back, and with it French Vogue, whose historic Album de la Libération was one of the most superb issues of any magazine ever published. The Americans had declared their independence of Paris, but found they could not do without it. Power must bow to authority; the Emperor must go to Canossa. American editors and buyers began flocking back again to Paris twice a year. The French climate and cuisine were more attractive than ours – and so later were the Italian – and the influx of foreign buyers to London was for a time reduced to a mere trickle.

ON MICHEL DE BRUNHOFF

… I must say a little about Michel de Brunhoff, who succeeded Mainbocher as editor of French Vogue…Until the Nazis wantonly killed his brilliant young son, in 1944, Michel, like Crowny, was another bubbling spring of bonne humeur…

During the German occupation of Paris Michel had kept a small team together and helped them make a modest livelihood while most of his colleagues had fled, through Spain and Portugal, to the United States. With his historic sense and artistic skill he developed a special sideline, of forging Christian baptismal papers for Jewish friends. One lady, the widowed mother of one of his employees, was in special danger of being forced to wear the Star of David.

He decided that as she had a German name she had better be supposed to have been born a Protestant in Alsace. He chose for her presumed birthplace a village which had been destroyed in the war of 1914-18, so that the records could not be checked. He took from his library a book published about the date of the lady’s birth, tore from it the fly-leaf, diluted his sepia ink so that it should have the appearance of age, and engrossed on it a baptismal certificate into the local Protestant church. Then he folded it and spent many hours rubbing its folds, until these were sufficiently worn.

When the lady presented it to the Commissaire aux Affaires Juives the official examined it carefully, handed it back to the lady, and exclaimed, ‘At last – one that isn’t forged.’

ON THE DUCHESSE D’AYEN

In sadder vein I recall the Duchesse d’Ayen, our French fashion editor till 1939, and still as I write a contributing editor with Maison & Jardin. She lost her husband, heir to the premier dukedom of France, in Belsen, and her son in the Liberation, while she herself spent months in Fresnes prison during the Nazi occupation. I remember her telling me, in January 1945, as we huddled over a small fire of wood from the Noailles estate, in one of the two rooms open in her vast house in Auteuil, how she had kept herself from going mad in solitary confinement by professional discipline. She mentally composed, she said, correct wardrobes for gaol-wear; beauty articles for the well-groomed prisoner; breathing exercises for moments when you were breathless with fear; methods of relaxation for times of agonizing nervousness.

ON THE BLITZ

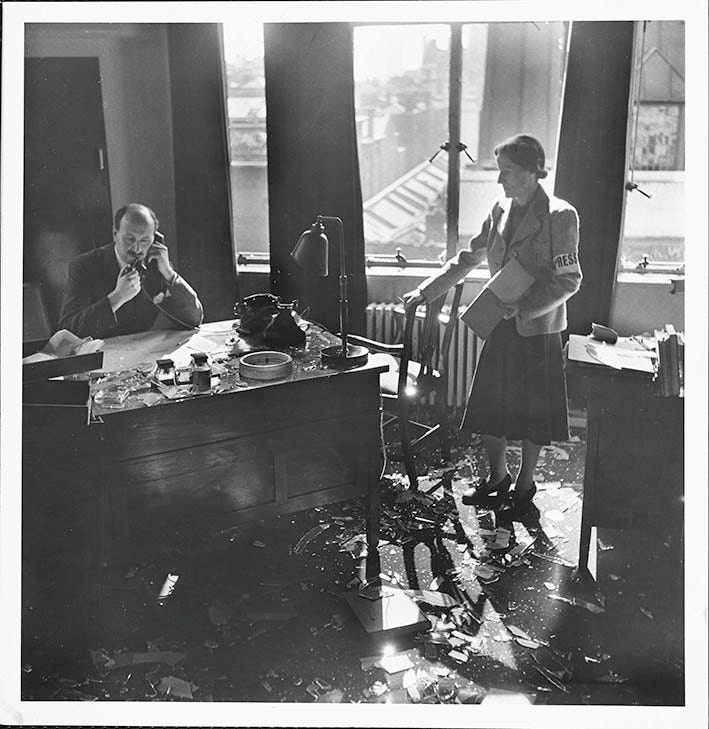

Bomb stories became a bore during the war… Our offices, of course, were continuously blasted, but so were everyone’s. I shall, however, sketch the loss of our [Vogue] patterns factory and publishing warehouse in Fetter Lane as a typical experience of those days. The old have forgotten, the young cannot imagine them.

It was during the last great fire-raid on London, in May 1941. I’d been on A.R.P. duty that night. We knew there was a heavy attack on the City, but even from the top of our highest local building could see no serious fires… At 6.30 a.m. I went off duty, and was going to bed when our company secretary rang me. Very conscientously he’d gone to London to see what had happened, and reported that our factory was a total loss.

I took the car as near as possible to the fires in Fleet Street, and got on with a press pass. By the Daily Telegraph building a number of manhole covers suddenly blew off as I passed, gyrating through the air like clay pigeons… I ducked down into Fetter Lane. The roof of our building and all the floors down to the ground had collapsed. Then the walls began to bulge, and I had to leave the scene of our disaster…

We lost 450,000 patterns and 400,000 magazines and books… I kept in our basement duplicates of all Vogue’s master patterns, films of the cutting charts, and one of each of the fairly simple machines needed for pattern-cutting and -folding. After the Fetter Lane disaster a few of our fatory staff came to Old Palace Lane [Yoxall’s home] and maintained production, though on a miniscule scale, until we could pierce the barbedwire entanglements of licences and permits and take new premises and extemporize replacement fixtures.

ON THE LAST YEAR OF THE WAR

We had a V-1 about a furlong away on the evening of the liberation of Paris, but I’d had so many drinks on the way home that this new pulverization seemed almost amusing. At least with the pilotless planes the blackout became pointless, and on the evening of 30 November 1944 a faint illumination was restored to the streets of London.

I am statistically minded, and keep track of numbers… it was during this month that I heard my thousandth air-raid alert.

As soon as Paris was reoped I started to try to get a permit to go there, to help restore our French edition… The eventual choice of the sea – I went on the first civilian cross-Channel boat – at least ensured my popularity on arrival, as I was able to take twenty pounds of coffee for our Paris staff… I was quite unjustifiably accomodated in the luxury of the SHAEF mess – which is to say, at the Ritz. This again increased my good-will, as every other day, when the hotel had hot water, I could give a bath to a woman from the office; or to phrase it better, I could provide her with facilities for taking a bath. For there were no hot baths at home for Parisian in that bitter winter. Our offices were totally unheated, and without light till 4.30 p.m.; one worked in hat, overcoat and driving gloves, chiefly by the illumination of church candles, which were ‘off the ration.’

Whereas in England we had, in 1944-45, all the necessities but no luxuries, in France they had all the luxuries but no necessities. There was plenty of foie gras, but no toast to put it on; plenty of champagne, but no milk. In England we hadn’t enough workers to do the work; in France, with its small military forces and disrupted communications, there wasn’t enough work for the workers to do.

We have all heard or read or seen so many accounts from WW2, but this series is unique. Many thanks for the research!