While I started writing this weeks ago, this piece is now in memory of William Klein (April 19, 1926 – September 10, 2022) who passed away this past weekend at age 96.

New Yorkers, go see the retrospective of his work at ICP today! It was supposed to end Sunday but has been extended through today, September 15.

The Australian Centre for the Moving Image: “From a Marilyn Monroe look-alike 'flasher' touting her wares at the corner newsstand to Hollywood studio moguls and perennial audition hopefuls, this record of 1970s Los Angeles is vintage Americana. The characters and telling cruelties of street life and celebrity obsession hold endless fascination for Klein; as his observations are inter-cut with rehearsals for an amateur pop opera 'Hollywood', the world gets just a little bit stranger.”1

A month ago, I went to see a screening of William Klein’s 1977 documentary Hollywood, California: A Loser’s Opera. A rarely seen part of his oeuvre, it was showing at Anthology Film Archive in connection with the recent retrospective of his work at ICP. Years ago, I read one mention of this documentary and have been looking for it since then—it is almost impossible to find, with the only print I know of in the collection of the Walker Art Center. Unlike Klein’s movies (Qui êtes-vous, Polly Maggoo?, Mr. Freedom, and The Model Couple, which are available from Criterion Collection) and some of his documentaries, it is unavailable in any home format—it is not even included in the 10 DVD set released in France in 2014. Look up Hollywood, California: A Loser’s Opera online and the only mention is a showing at the Tate Modern in 2012. Period newspapers hold no more info—the most I found on it were a few mentions in academic articles on his documentary work, but these did not include any descriptions or analysis (likely the scholars were unable to watch it for themselves).

According to Des O’Rawe, “Klein’s documentary film practice has always tended towards a cursory, essayistic method, probing the subject matter rather than seizing a dramatic revelation: an executioner when it comes to taking a photograph, Klein is more akin to a inquisitor when making a film.”2 Often his documentary work is lumped in with the Direct Cinema style of Frederick Wiseman, D. A. Pennebaker, Robert Drew, and the Maysles brothers, though stylistically it falls closer to cinema verité—while Klein is never seen and barely heard, he is as much a participant as those on screen.3

Hollywood, California: A Loser’s Opera is the first in a trilogy of documentaries Klein made on contemporary American culture and society; it was followed by Music City, USA (1978), and The Little Richard Story (1980). An American long based in France, his perspective is that of a shapeshifter—moving from insider to outsider and back again. There is no plot or story—Klein simply arrived in Los Angeles and filmed. As this documentary is told through glimpses—small vignettes only connected through place (Los Angeles) and the sense of place that pervades each interaction (the mythical idea of “Hollywood”), so too will this newsletter. With no primary nor secondary source material on its production available, this is more a spooling out of some of the vignettes. The people and places he recorded feel emblematic of the American Dream—the gloss of glamour on the surface, the cruel degradation and striving beneath.

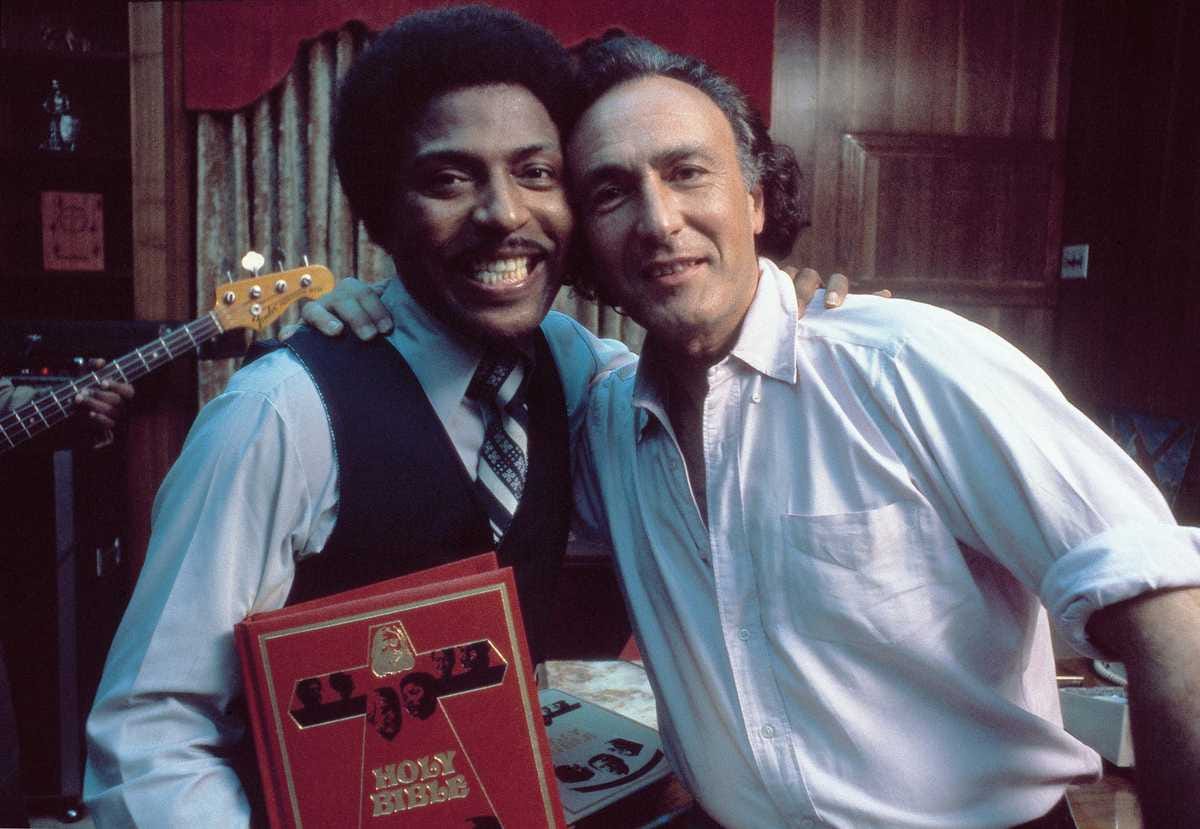

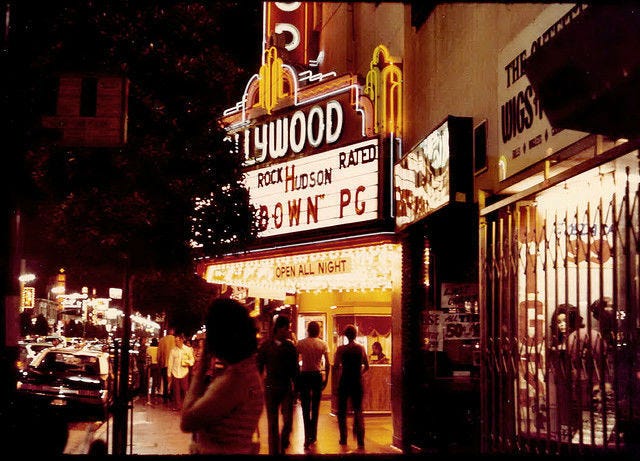

The neon lights of a movie theatre at night—beckoning customers to visit Fraternity Row—opens the documentary, reminiscent of Klein’s first foray into film. In 1959 he made an experimental short, Broadway by Light (watch below)—an impressionistic, poetic exploration of Times Square. As the lights of the Hollywood Theatre (then Mann’s Hollywood) sparkle, we are taken into a music studio to view the rehearsals of a pop opera about Hollywood. Several of the individuals are named onscreen but the only name I recall is Tony Berg—then a session musician for bands like Air Supply, later a music industry dynamo. My research has yet to pull up anything on this musical—it likely seems never to have been produced.

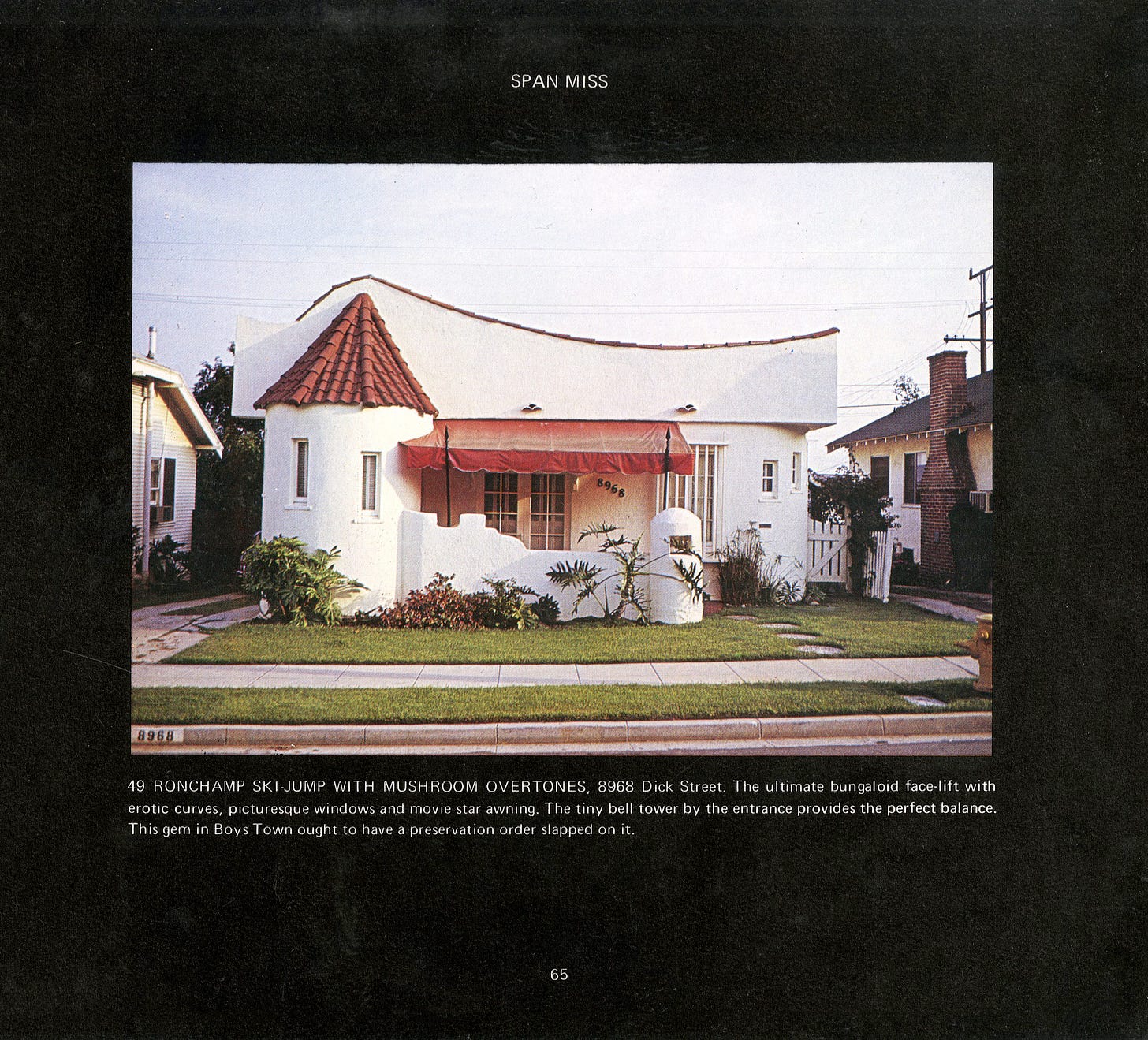

As they try to work out the lyrics and vocal parts, their voices carry over long driving shots through Hollywood. Likely taken early in the morning, the streets are empty, dirty and grim. Having just been in LA last week, much of this still looks the same—Klein films the low-level dwellings and businesses that stretch for miles across the city, the juxtaposition between luxury and the decrepit flattened into one seamless vision of Americana. It is reminiscent of Charles Jencks’ Daydream Houses of Los Angeles, which was published the following year: “A natural, first response to the exaggerated houses of Los Angeles is one of despair. They display obvious—much too obvious—signs of snobbery, status-seeking and kitsch; they mix motifs pillaged from every known style, combine them in an ungrammatical way and are brazen enough to do this with explicitly shoddy material. This, it seems to me, is an inevitable, even necessary, part of one’s response to these houses, but it’s a revulsion tempered by other feelings, those of attraction and amusement, the delight of shock in seeing custom broken.”

Some photos of driving around Los Angeles by Anne Laskey, from 1978-79:

A group of wannabe actresses stands in an empty black warehouse space. All are dressed in sweaters (many cowlnecks), some with coats and at least one knit cap—considering this was filmed in LA in late spring and early summer, it must have been a cold studio. They are fresh-faced, save a few more jaded-looking ones. One by one they go down the line, introducing themselves, talking about where they are from, how long they have been in Hollywood, and what they do to support themselves. It becomes evident that the freshness of face and joyful mood corresponds to how long they have been in LA and how much work they are getting—the happiest are those who have been there the shortest or have found the most acting/singing/dancing work. Those that have been relegated to long-term secretarial or accounting jobs have a tinge of bitterness, especially when Klein asks them all whether they expect to make it in Hollywood or not. Of the women featured, the only one whose name I caught was Nikki D’Amico—she told Klein that she had to make it, there were no other possibilities. Over forty years later, she looks identical—same closed-cropped black hair, pale face with sharply drawn features. All the women act for Klein’s camera—not auditioning a specific role but instead playing the part of a Hollywood hopeful, the undiscovered ingenue.

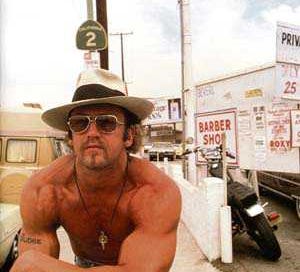

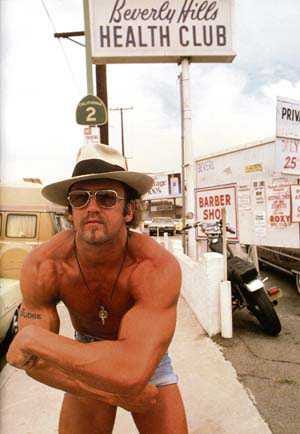

By a transit van in an overgrown parking lot, a quick-draw artist practices his moves. Clad only in cut-off jean hot pants and a hat, his tan muscles gleam in the fading sun. He talks (revealing the worst teeth I’ve ever seen) about quick-draw, bodybuilding, and nights working at an “interesting club for women.” Klein then follows him to the Beverly Hills Health Club where he grunts and moans while lifting weights. The weights all chrome in a room of glossy brown walls and a red-and-green tartan carpet, the club itself is a wonder for the eyes (I dearly wish gyms still looked like this and tried desperately to find photos). One scene memorably shows him close-up, struggling to squat a heavy barbell—when he steps away, a crowd of elderly men dressed only in towels are revealed. His fascination with weightlifting and his body are later called into question by a young woman sitting next to him at a diner counter—as he explains all the specific foods he eats throughout the day to build muscle, she asks him why. For him, it’s about looking good—the pursuit of external physical excellence is so that others will find him attractive, not for health. She scolds him, saying that this diet and obsession isn’t what good Jewish boys do. Later there is a short scene of him giving a massage to a transvestite or transexual (the person’s identity and gender expression are not discussed, and at the time of filming they would likely have had a different understanding of their gender); what first appears to be businesslike becomes flirtatious, perhaps revealing something of the muscleman’s work at an “interesting club for women.”

Alan Carr at work—first a view of his palatial mansion in Beverly Hills, Hilhaven Lodge, then talking with two assistants in a glassed-in alcove hung with Boston ferns. Then famous as a talent agent and promoter, he is at work producing his first film, soon-to-be mega-hit Grease. Behind his desk at Paramount, he talks about the Hollywood machine and then walks through the throngs of teens dressed up as greasers eager to be extras in the film. There is little in what is said or shown that foreshadows the success Grease would become; no mention of the stars nor the songs, simply desperate costumed hangers-on. Hilhaven Lodge is now owned by Brett Ratner, who has named a whiskey brand after it—you can see the sunroom in the image below.

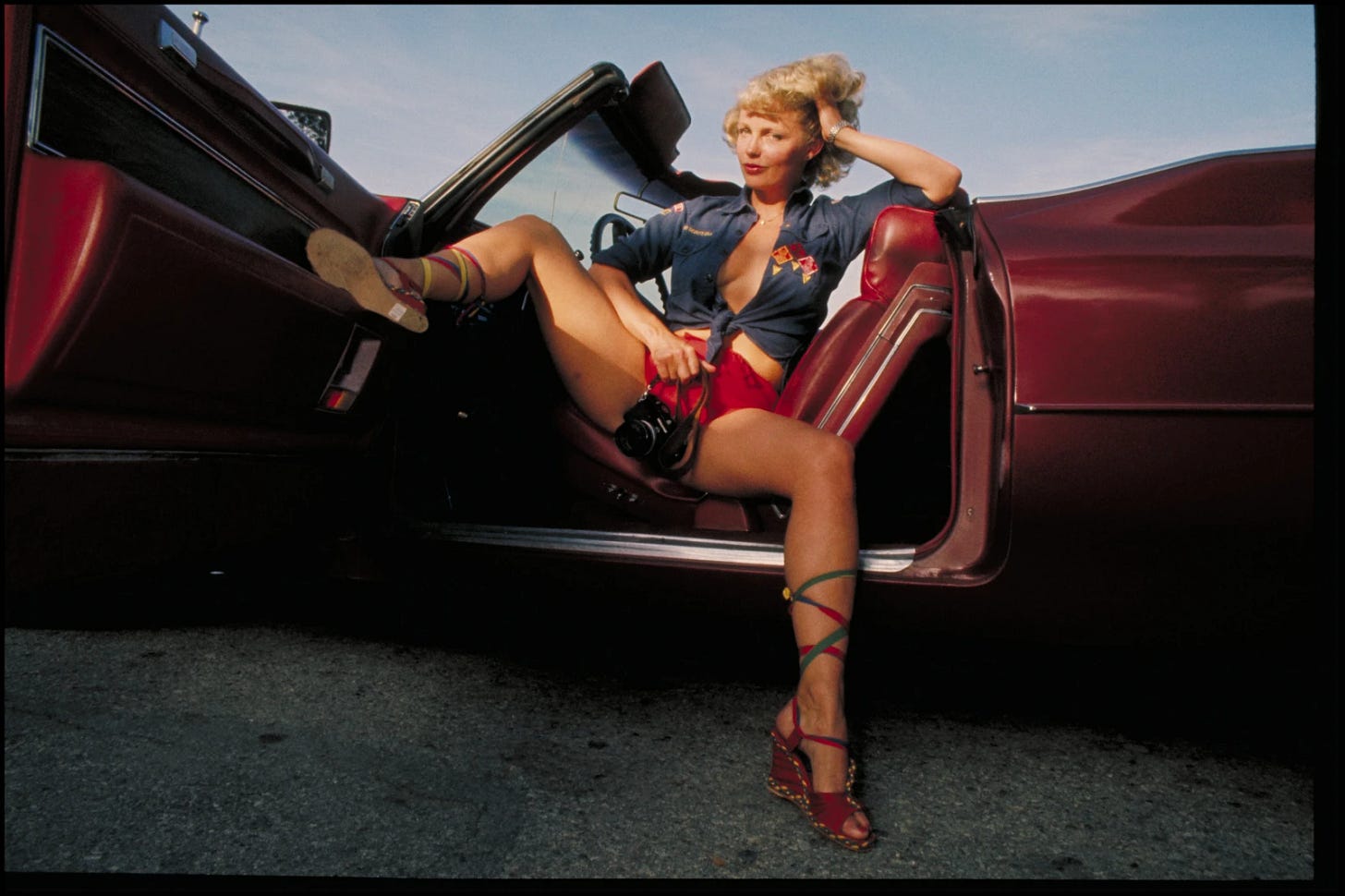

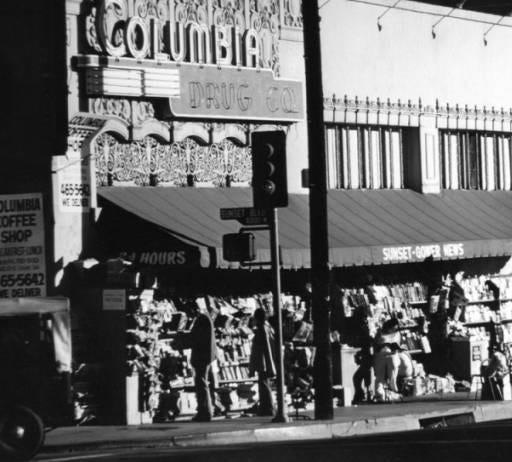

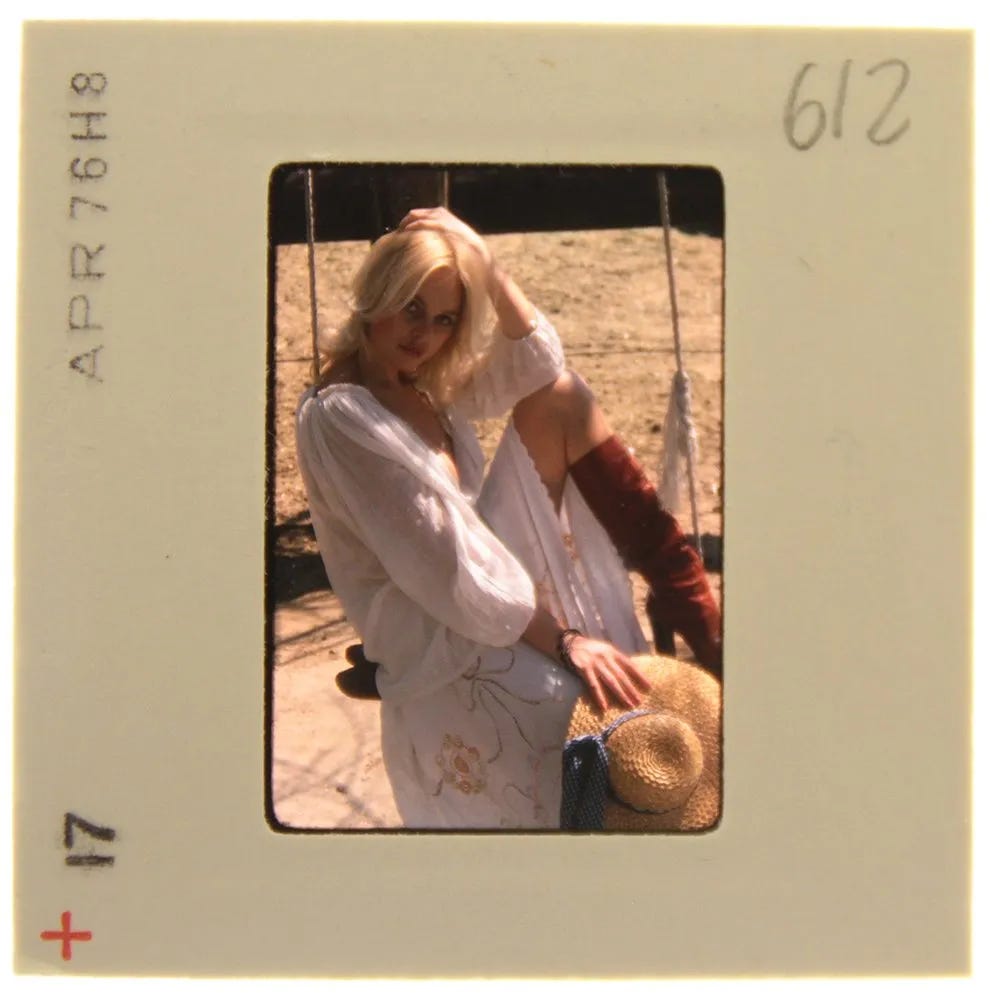

At the Sunset-Gower Newsstand, pornographer and model Suzi Randall poses with the June 1977 issue of Hustler that features a very explicit pictorial of self-portraits by Randall. The blonde bombshell flashes open the magazine then quickly lifts her skirt, laughing at pedestrians shocked by her semi-constant mooning. Arching her back over a pile of newspapers, Randall exhibits the provocative nature and toned body that first brought her attention as a fashion model, actress, and erotic model, before she decided to step behind the camera. Suze was the first female Playboy photographer to shoot a full-frontal, the first woman to sell her nude photographs to The Sun, was staff photographer for Playboy from 1975 until 1977, then staff photographer for Hustler from 1977 until 1979. In 1980, she became one of the first female porn directors. She continues to shoot and has her own porn site. Later in the documentary, she is shown photographing the young porn actress Serena, an angelic blonde. As Serena writhes her lithesome body in time with the music and Suze’s flash, the pair talk about Serena’s life—from teenage runaway to then living in the Valley as a single mom, shooting porn. You can listen to an interview with Serena on the always great Rialto Report (NSFW).

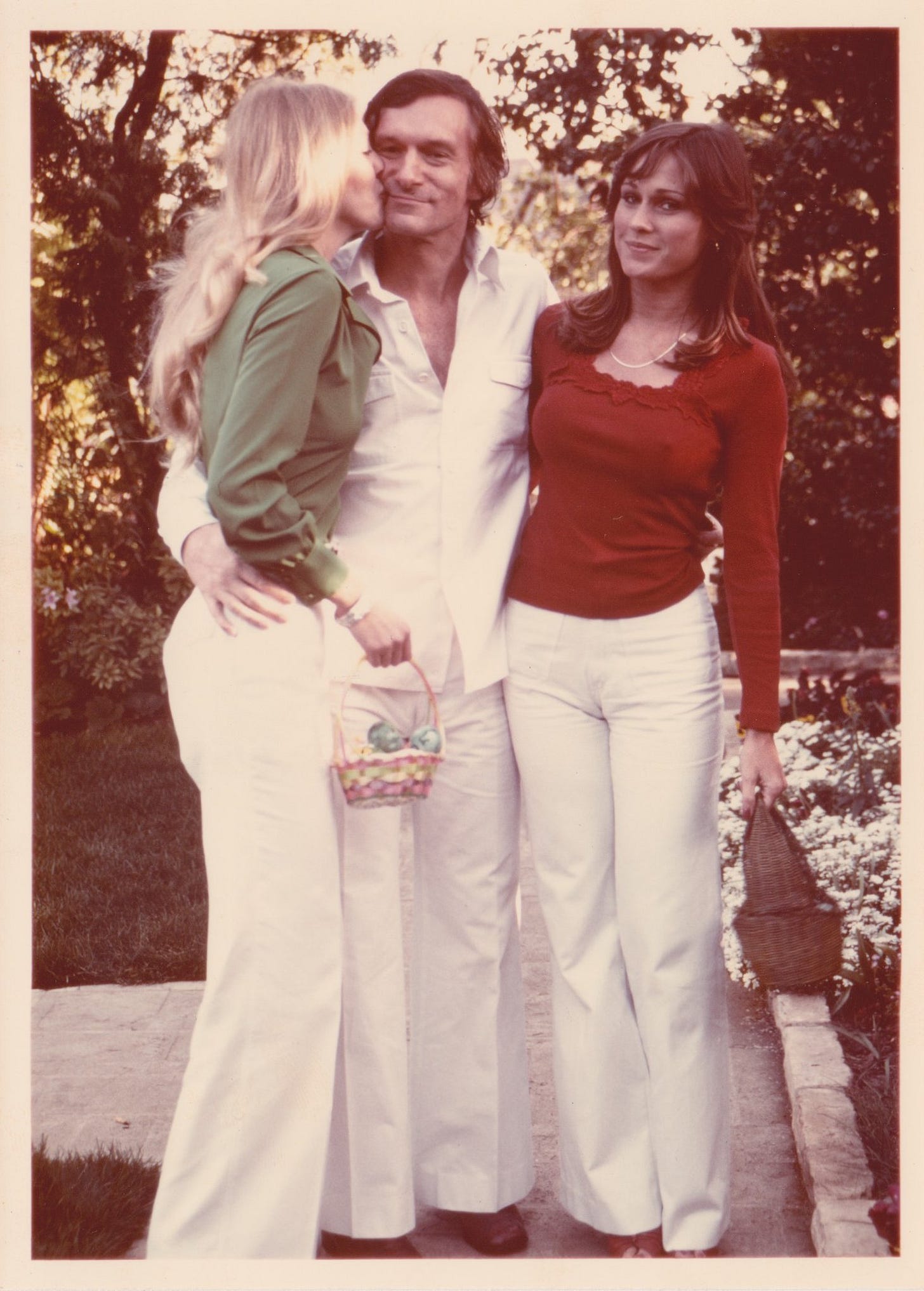

More Boston ferns hang throughout a clear plastic marquee set up in the garden of the Playboy Mansion for the announcement of the 1977 Playmate of the Year. Hugh Hefner gives a speech with 1976’s Playmate Lillian Muller and Suzi Randall (who discovered Muller) standing by, before presenting Patti McGuire with the honor—she’s later filmed showing off her $10,000 check to her disbelieving friends. McGuire has been married to tennis star Jimmy Connors since 1979, but at the time she was majoring in political science at Southern Illinois University and working as a bunny in the St. Louis Playboy Club; a cute all-American girl, she appears overwhelmed with her sudden success.

Interspersed between these vignettes are short scenes of more driving, as well as small segments from the audition and the rock opera rehearsal. Klein builds a portrait of the city by layering all these diverse people and moments together—the rich and the poor, the successful and the striving. If you ever get the opportunity to watch this documentary (or any of his documentaries), I highly recommend you do so. They are experiential, not didactic; you feel like you are right next to Klein driving around LA (or in the midst of a planning meeting during the 1968 student riots in Paris or in a crowd at the 1969 Pan-African Festival of Algiers)—Klein places you into these realities and by gradually revealing disconnected parts of them, exposes the whole and soul of the place or event.

The only William Klein documentary I found in full online is Muhammad Ali: The Greatest (1969).

Below are trailers and clips from some of Klein’s other documentaries.

Australian Centre for the Moving Image, “William Klein: Hollywood, California: A Loser’s Opera,” Tate.

Des O’Rawe, “Eclectic Dialectics: William Klein’s Documentary Method,” Film Quarterly Vol. 66, No. 1 (Fall 2012), p. 50.

This is a good overview of the differences: https://www.nyfa.edu/student-resources/cinema-verite-vs-direct-cinema-an-introduction/