Valentino Time

Social Unrest and Fashion's Reaction, 1975

During the social unrest and political violence that rocked Italy throughout the 1970s—known as Anni di piombo or Years of Lead—fashion designers still had to produce collections of desirable clothing.

The first few years of the decade saw economic growth shrink as inflation accelerated, with a depreciation of the lira worsening the balance of payments. When OPEC imposed an embargo on oil exports to the US and other Western nations, oil prices nearly quadrupled in 1974, quickly sending Italy into a recession. With the country threatened by insolvency, Premier Mariano Rumor of Italy and his Cabinet resigned that June. Inflation peaked in 1975 at 25.68%, and unemployment soared. Strikes and protests were followed by waves of kidnappings, murders, and bombings by both far-right and far-left extremists.

“Fashion is a wheel that turns, a dress is a dress. You can try to take inspiration from 1800 or 1925, but you remain influenced by the context in which you act… Political changes impose greater rigor in creation, life is no longer the same as it was a few years ago, and even if a haute couture collection must have a certain level above all in quality and in relation to its clientele, and if this clientele does not seem to be affected by these social changes, we cannot forget them.”

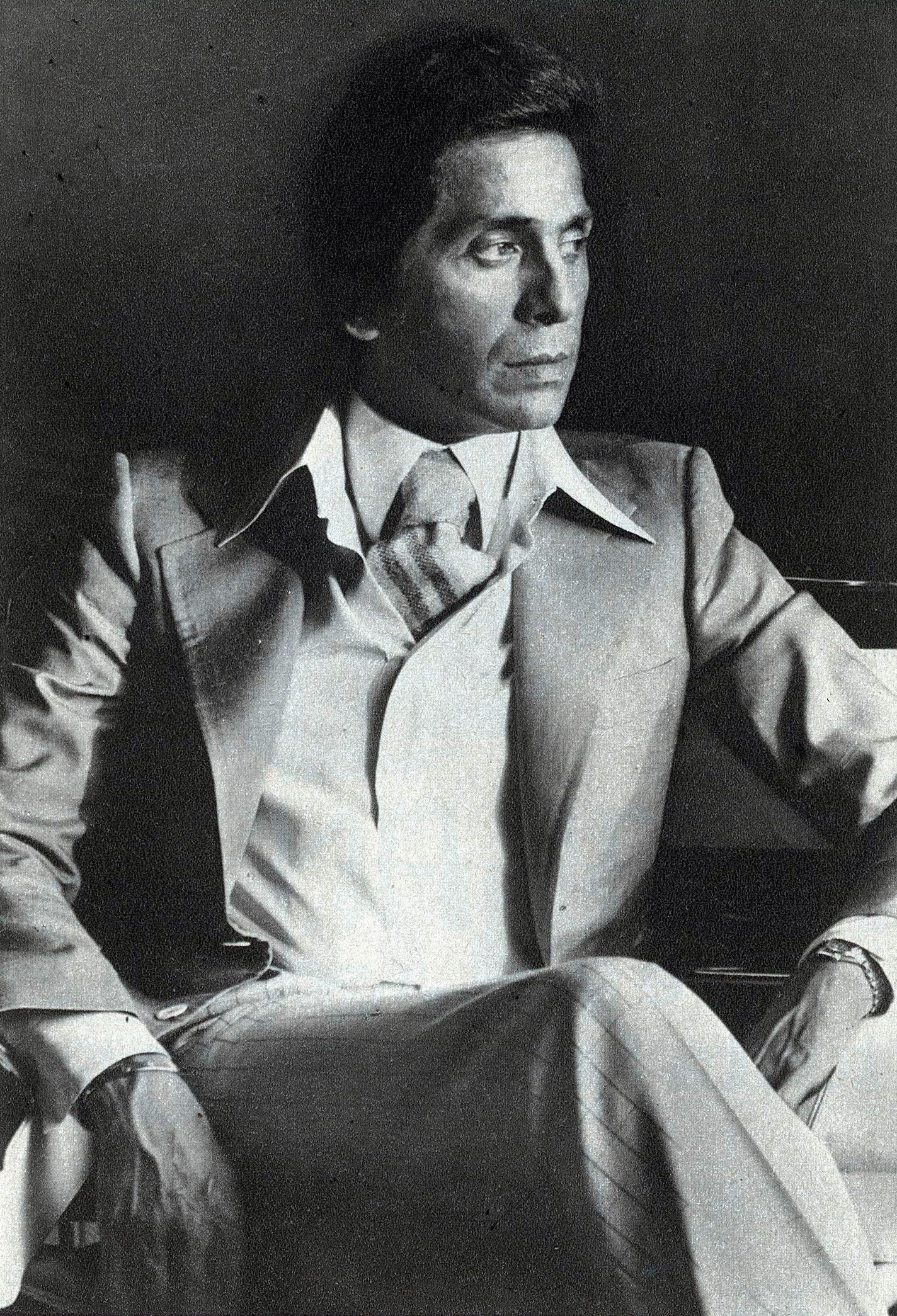

Against this backdrop, how does one keep creating? Does one react in their collections? Or continue to produce beautiful clothes for those rich enough to be unaffected by unrest and turmoil? The short-lived Italian magazine Libera (which I’ve written a bit about before) posed some of these inquiries to Valentino Garavani, who, by 1975, was already living as grand a life as many of his haute couture clients. While he states that he is not involved with politics, he does point out that his job is to sell as many clothes as possible to keep his two hundred employees working, and therefore, he can’t concern himself too much with the sources of his client’s wealth—he needs to design clothes they want to spend money on so that he can pay employees to make them and not bring his own emotions or beliefs into it. An interesting perspective (not one I necessarily agree with) for questions that continue to play out in the fashion industry today (the comments on this post about Monse designing the Blue Origin uniforms reveal what many consumers think about current designers choosing money over ethics).

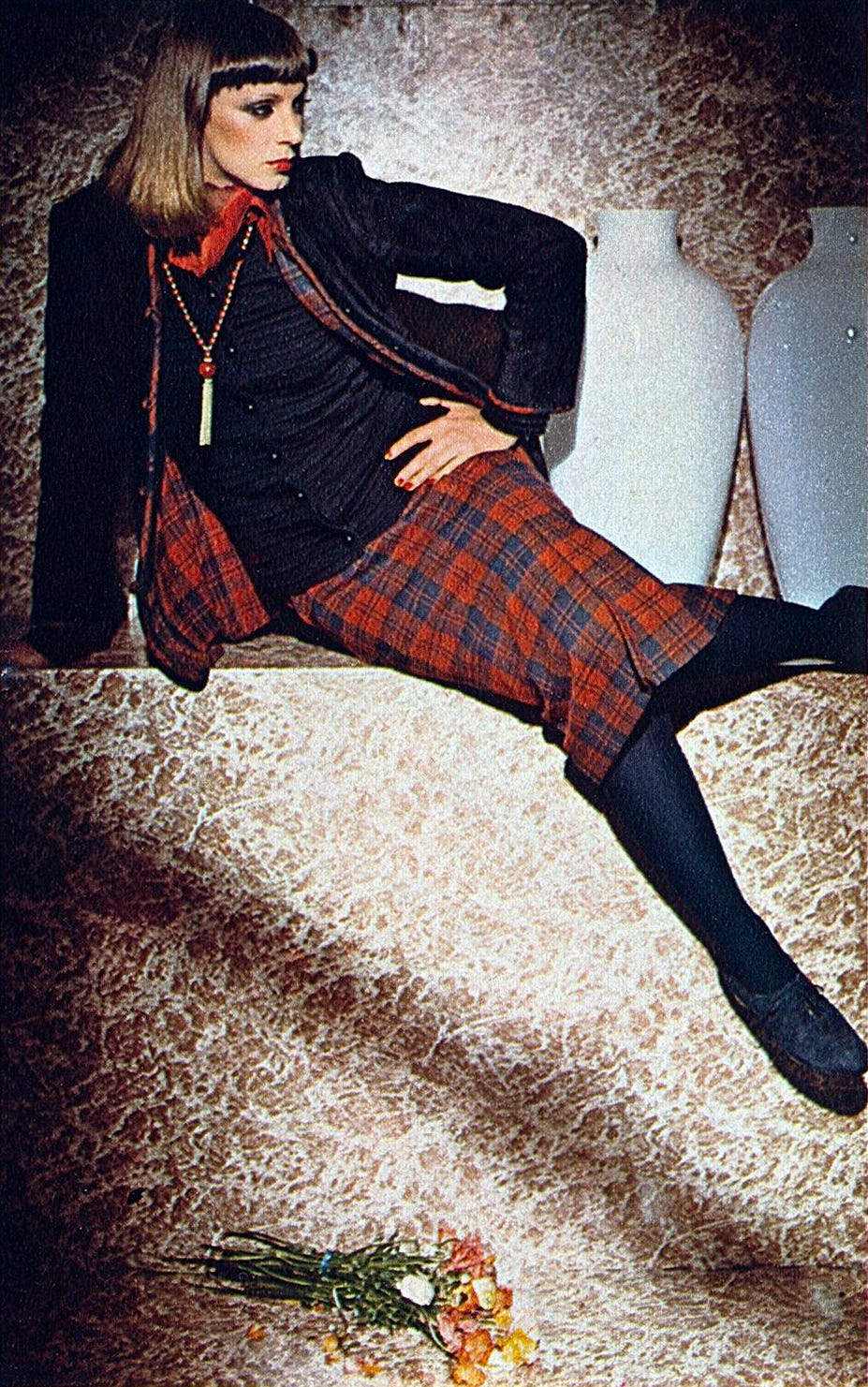

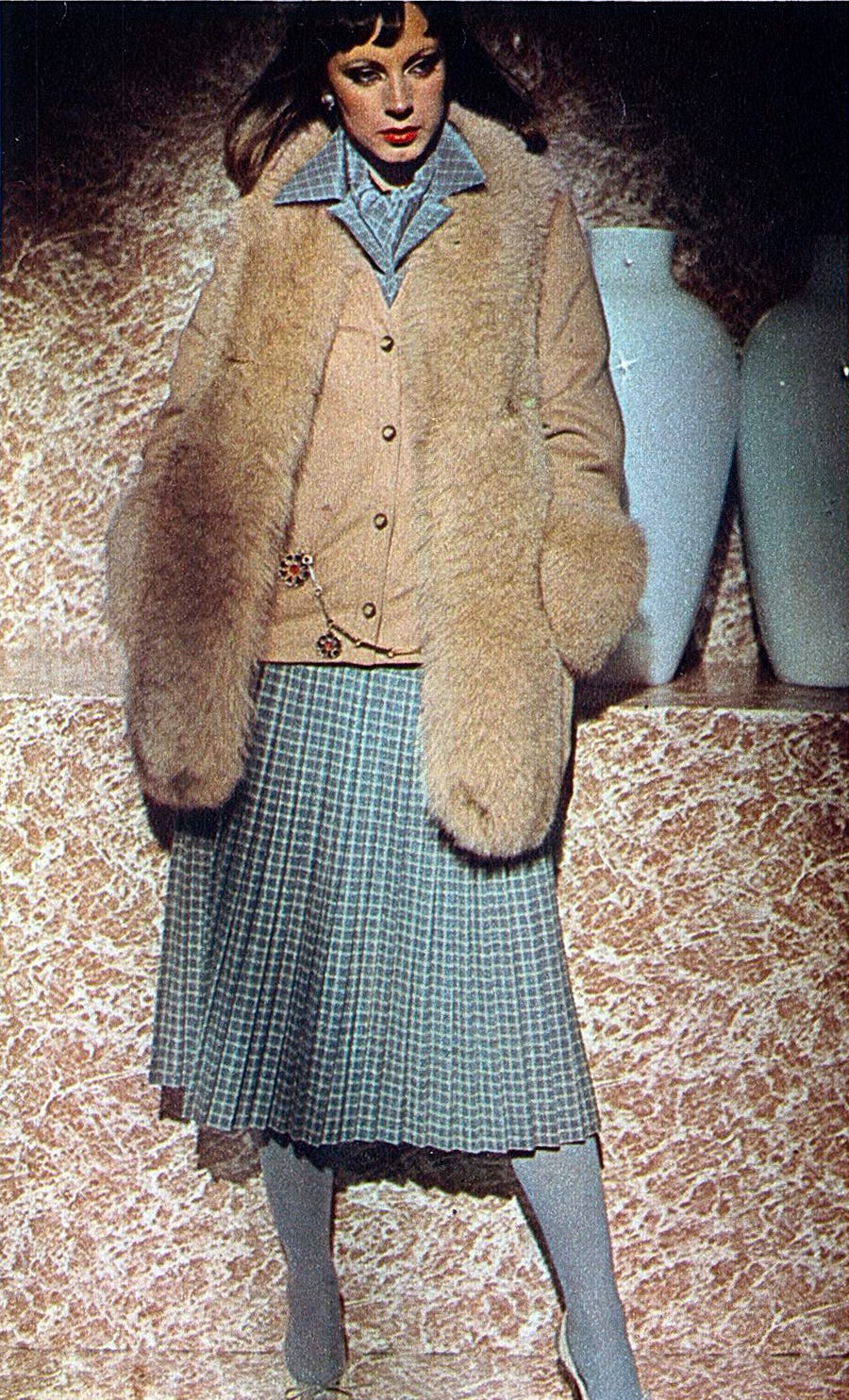

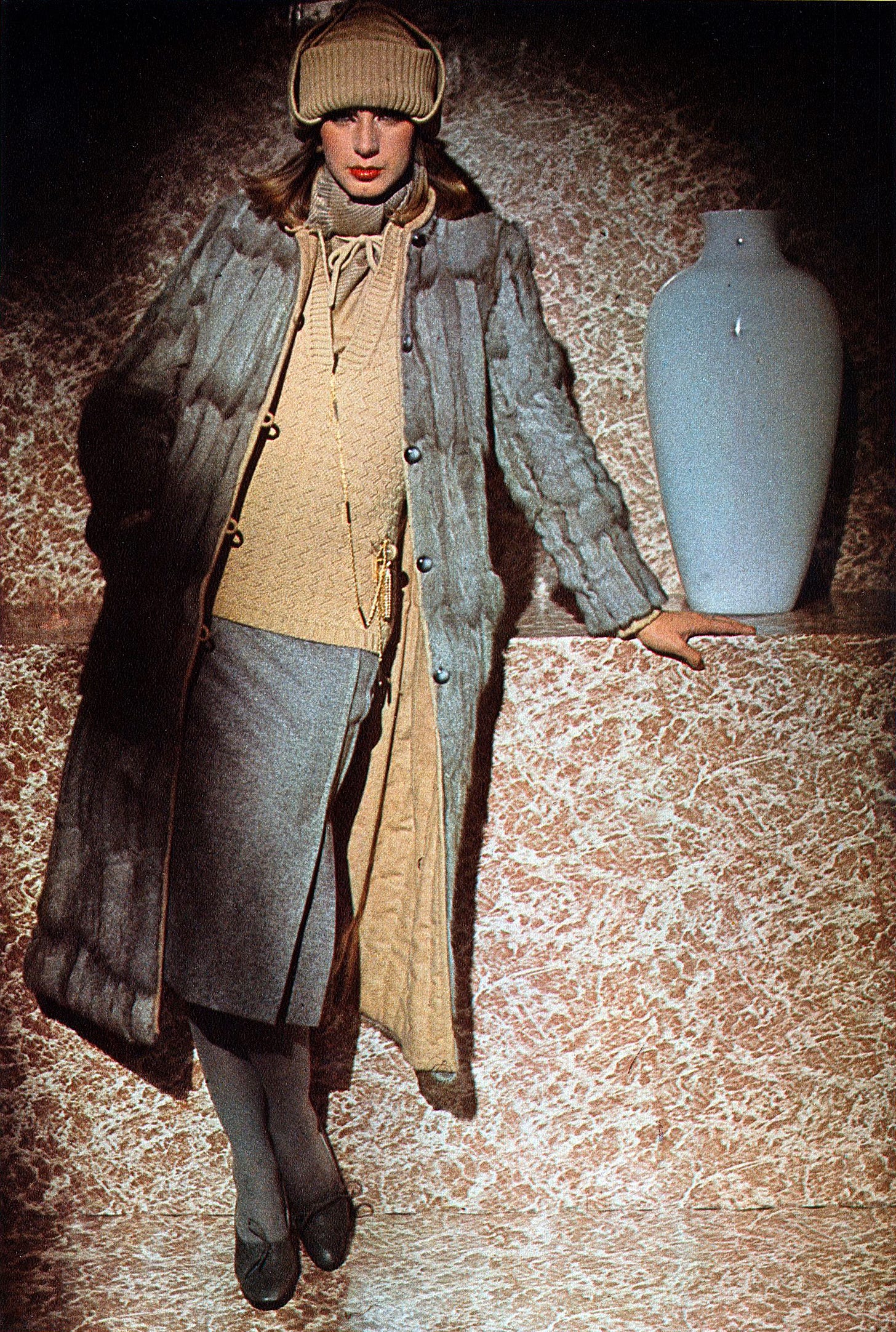

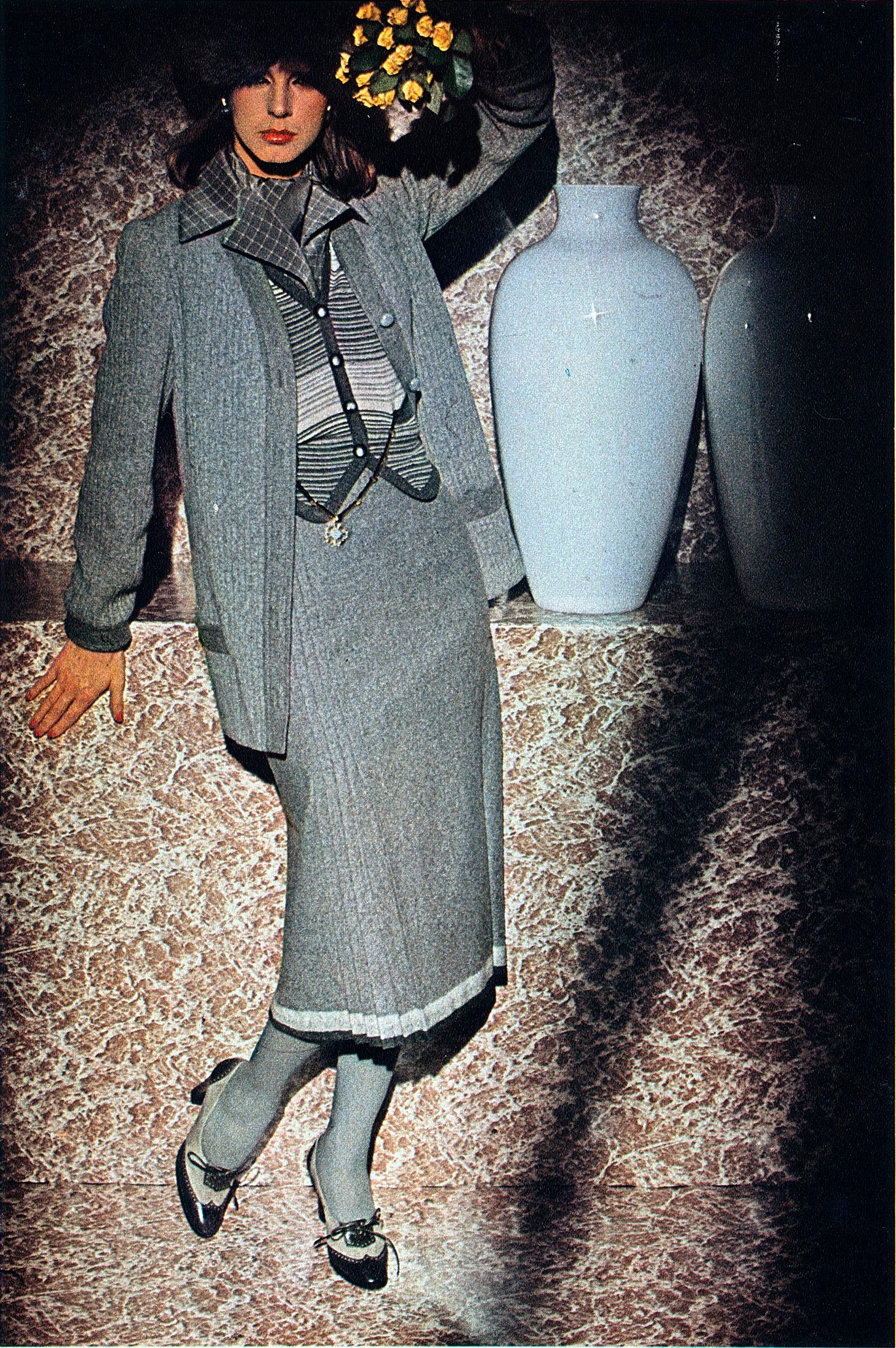

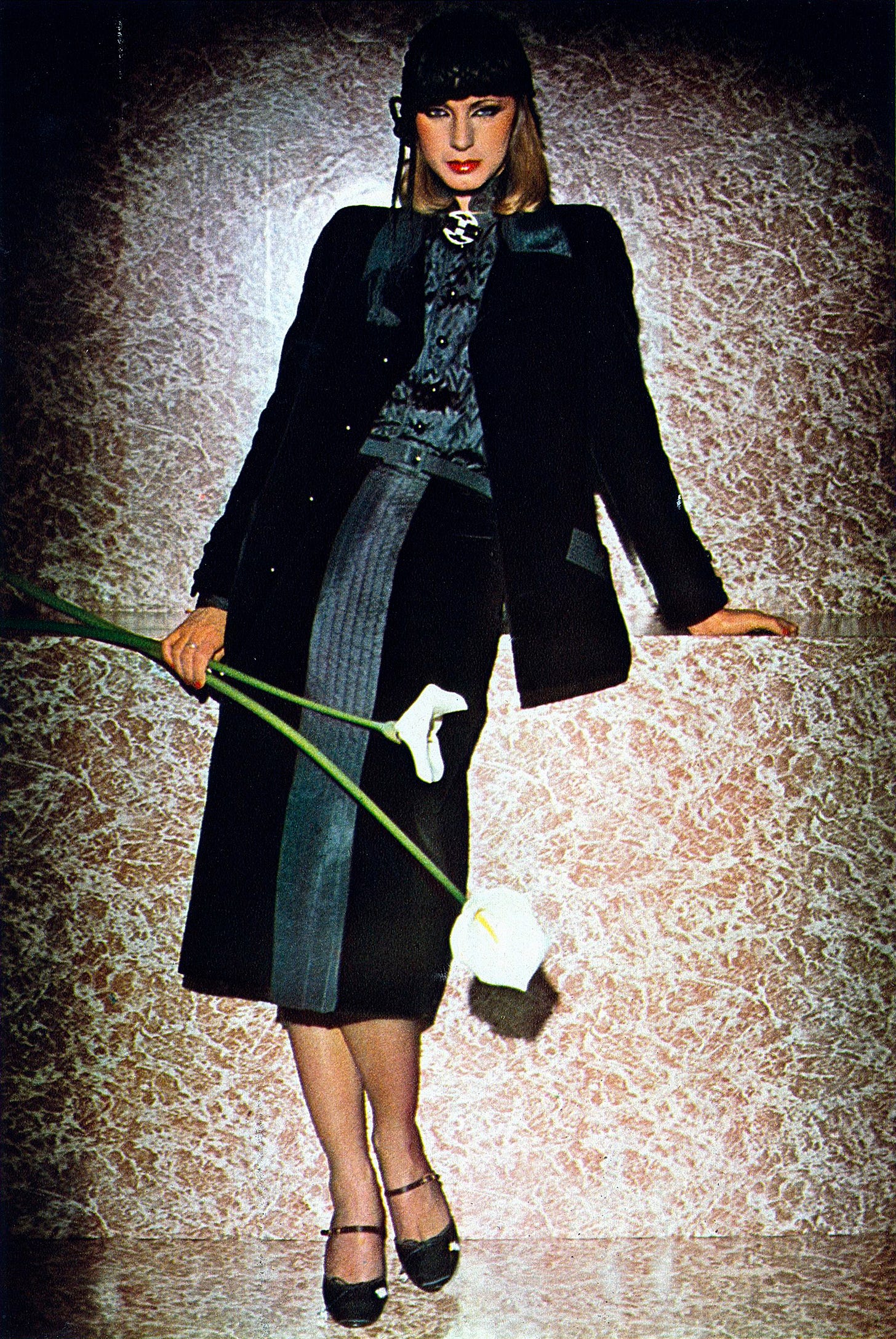

The Time of Valentino: An absolute preview of the autumn-winter '76 ready-to-wear collection from the most prestigious name in haute couture

Libera, July 1975.

Interview by Lino Pinto.

Photographs by Roberto Rocchi. Shoes by Mario Valentino for Valentino / Jewelry by Ugo Correani - Manoa 2 - Borgonese / Hairstyle by Alba / Makeup by John Paul / Tights by Malerba - Lamber's / Terrace Zegna Baruffa / The white opaline vases are by Venini.

Libera: Valentino, when did you start and why?

Valentino: Since I was a boy, I was interested in everything that was drawing, beautiful things, elegant women, I looked at all the magazines of the time. At 17 in Milan, I decided to do fashion, leaving the classical high school for a school called "L'arte del disegno e della moda", at the same time, I studied French. I moved to France to take a test. There, I still studied fashion drawing and modeling. It was 1952, I was hired for 5 years by Jean Dessès, one of the most famous tailors of the time. At that time fashion was quite complicated, and for two years I designed for Guy Laroche.

After these experiences, I felt good enough to set out on my own to open a tailoring shop. In Via Condotti in 1960, my first collection for a private clientele. In 1961 my first "official" collection at Palazzo Pitti. In the meantime, I had moved from via Condotti to via Gregoriana 54. At that time Italian fashion was booming and I was part of it: buyers, especially Americans, famous clients, international press.

Libera: Jackie Kennedy seems to me to be a very important stage, a fundamental advertising promotion. How did you meet her?

Valentino: In New York, nine months after the assassination of President Kennedy. I was invited by Mrs. Kennedy to design some dresses for her. I began to dress her and given the personage, my name had a very important resonance throughout the world. In the meantime, I had moved to this atelier presenting an all-white collection, which had enormous press resonance and created the beginning of my success and of the "V".

Libera: What determines and influences the taste of the haute couture creator? What contributions have the changes in costume in recent years made to haute couture? Political changes for example, to what extent have they influenced?

Valentino: A true fashion designer lives and works by reading books, seeing exhibitions, frequenting museums. Fashion is a wheel that turns, a dress is a dress. You can try to take inspiration from 1800 or 1925, but you remain influenced by the context in which you act. In these years, there have been enormous changes decided unanimously by the great creators. The 50s were a bad period for fashion: there was no line, there was no cut, there was no chic, everything was loaded and lacking in proportion. From 1958 to 1965 everything was scaled down: the small trapezoid lines, a very bare style, shoes with low heels. Then we returned to a great confusion: long skirts, short skirts, the revival of the 40s, gypsy rags etc... Now everything is stabilizing. In fact, even haute couture designers have changed their way of seeing women. Political changes impose greater rigor in creation, life is no longer the same as it was a few years ago, and even if a haute couture collection must have a certain level above all in quality and in relation to its clientele, and if this clientele does not seem to be affected by these social changes, we cannot forget them.

Libera: The women that Valentino dresses—the various empresses, queens, princesses, actresses, captains or wives of captains of industry are the privileged ones, we know—but Valentino—not the one proposed in the magazines, amongst luxurious villas of a rich oriental prince who studied in Europe—are you aware that we are experiencing a housing crisis, for example, that many women before buying a blouse in a department store have to do the math and that we live in a world in full economic crisis?

Valentino: This stardom, this magazine character, created at a time when the public was asking for it, was looking for the myth of the fashion creator, has been surpassed, I hope, by the reality of a company head who knows social and human problems without forgetting the meaning of his product. It is clear that I remain a lover of beautiful things and I try to give them to a clientele who is looking for this; on the other hand, do not forget that the basis of my creation is quality: that of the material and of the execution, and if you want, you can consider this the meaning of Haute Couture today: not products destined to run out in a short time, but something that lasts. This is as long as there is Haute Couture and Fashion: when all this no longer has any meaning, when there is no more demand, when the inspiration of a creator is no longer even useful to those who produce clothes for the masses, then it will truly be the end of fashion.

Libera: But let's talk about the reality of these clients of yours. For example, the workers who work in Mrs. Patiño's mines in Latin America are paid miserable wages, more or less 25,000 Italian lire a month. What do you think?

Valentino: Do you realize that you are talking to someone who employs 200 people here in Italy alone, directly, without mentioning the hundreds of thousands of artisans who revolve around the world of fashion? And you don't call this a social conquest? On the other hand, I am not involved in politics and I cannot forget that every day I have to give work to my employees, and that my job is to make as many clothes as possible.

Libera: Last year, the feminist movement stopped with signs in front of your atelier during a fashion show. What did they accuse you of?

Valentino: I don't know, I was in the middle of the fashion show but I don't think they accused me, but the woman who tries to conquer the man through a dress.

Libera: Why did they choose you and not someone else?

Valentino: Because they used me as an advertising medium.

Libera: What is your ideal client like? Does your woman have a very specific silhouette?

Valentino: Yes: she is a rather slender woman, not very exuberant, with normal proportions.

Libera: Your latest winter ready-to-wear collection offers a new line already tested in your latest summer haute couture collection.

Valentino: It is a very simple line, with light accents of sophistication, we are returning to essentiality.

Libera: How did you arrive at this lean, tube-like line?

Valentino: Through a process of saturation and rejection of wide, soft and overlapping lines. I automatically thought of modifying the silhouette, and I tried to make it sexier. The great desire of women at the moment is to show off their body with tight-fitting, sexy but discreet things.

Libera: Your two lines, haute couture and ready-to-wear, do they differ in style and prices?

Valentino: No, stylistically there is always a common thread that links the two. Haute couture is more limited, pret-a-porter is larger. The prices of the second line are quite accessible, but deriving from haute couture you cannot go down to the level of prices that are too low, the structures do not allow it.

Libera: What interests and excites you beyond haute couture?

Valentino: Furniture, art: Chinese and Egyptian in particular. I love music, cinema, traveling. I am very stimulated by the artistic avant-gardes, but what I prefer and find even more important in the 70s is the opportunity that these difficult years have given us to have to try to know in depth the people around us, to have a human dialogue with them. The previous years had taught us only superficiality in relationships.

The Poetic Fashion of Pino Lancetti

Alongside the profile and editorial on Yves Saint Laurent’s designs in Libera’s 1975 spring fashion issue I discussed last week, the other major designer portfolio is on the Italian designer Pino Lancetti. The clothes and the textiles are so beautiful (just look at that dress below!), I felt I had to share the photos and some background on the designer the Italian fashion press called “"il sarto pittore" or "the tailor painter.”

At the Court of Yves St. Laurent

Today I thought I would share some unseen Yves Saint Laurent photos and a short interview. Published in the long-forgotten Italian magazine Libera in 1975, in its spring fashion issue, Saint Laurent is presented as the “king of all fashion,” the sole designer still truly influencing the whole industry.