When I think of Thanksgiving movies, I think of Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm (1997) and Woody Allen’s Hannah and her Sisters (1986). While Allen’s film takes place over two years and three Thanksgivings in the mid-1980s, The Ice Storm is set over one fateful Thanksgiving weekend in 1973. A real atmospheric masterpiece, it is the artful production and costume design that imparts so much of the mood—it reads as the Seventies but with an icy detachment that imparts extra layers to the fraught lives of the characters. Based on Rick Moody’s 1994 novel, according to writer/producer James Schamus, “The biggest hurdle in adapting the book was to create, in a visual way, the emotional effect that book accomplished through the use of [the narrator’s] voice.”1

To do so—as Ang Lee hadn’t lived through this period in the US (he first came here in 1978)—Lee approached it as a period piece, similarly to how he took on his previous film, Jane Austin’s Sense and Sensibility. Costume designer Carol Oditz, production designer Mark Friedberg, and cinematographer Frederick Elmes sought to re-create the early seventies but through the prism of “the era’s art, specifically the work of the photo-realists, who painted photographs in a style that is both hyperreal and at one remove from reality—evoked by the variety of reflecting surfaces seen in the film—and the op artists, who deployed contrasting visual elements to create vibrating surface tensions on a single plane.”2

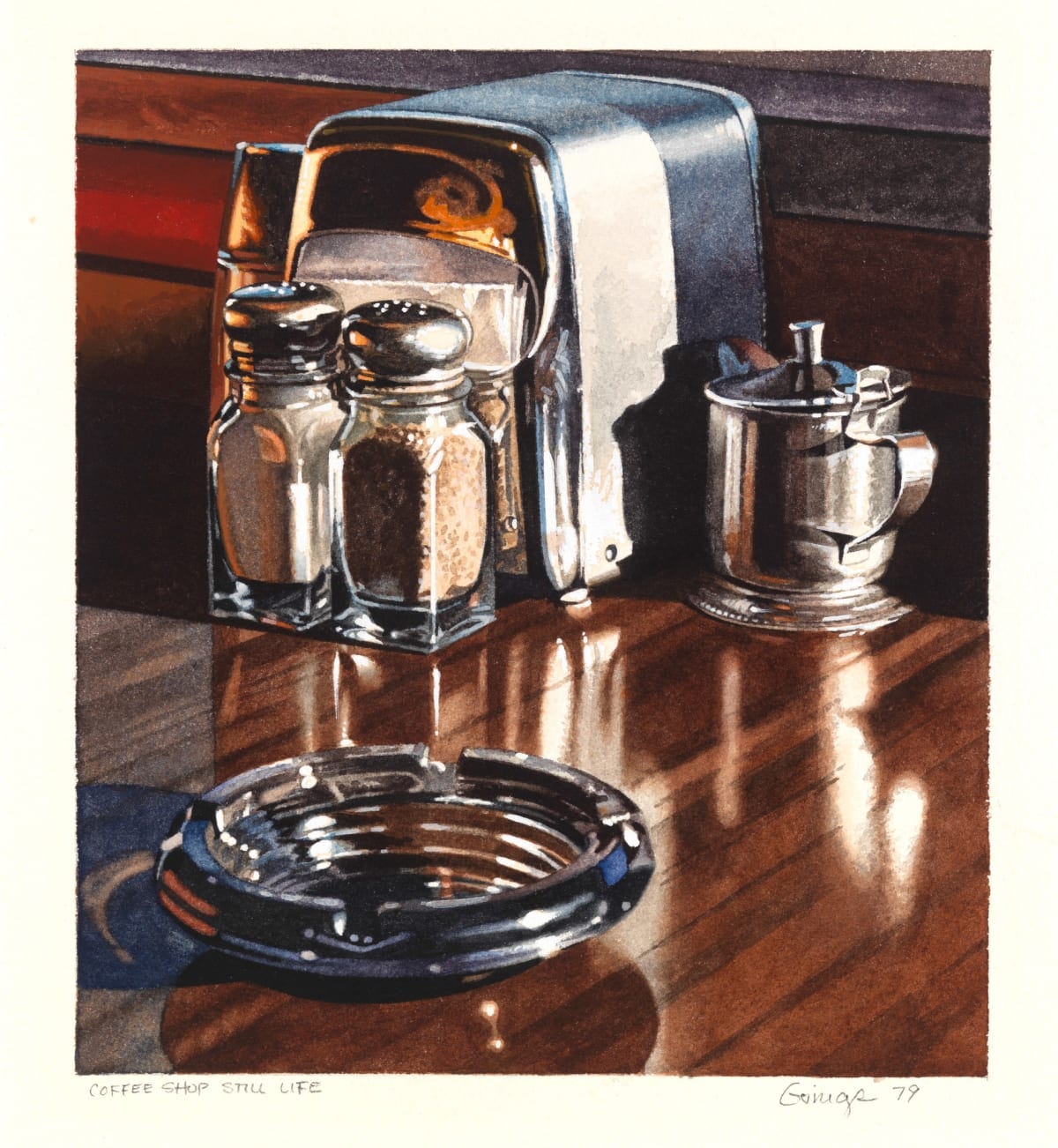

Lee and Elmes looked to photo-realist painters like Ralph Goings (above) to provide the visual key for the first half of the film; for Lee, “Art direction and cinematography usually work to support the actors, but I wanted our settings and their look to represent an obstacle to humanity. I tried to build this tacky world in the first half of the film, which is how the notion of photo-realism came into my mind. By ‘photo-realism,’ I mean a removed, intensely objective view of things, including people. That required higher contrast, a lot of reflective material such as glass and metals, and a lot of defocused subjects and negative space in the compositions to distract the audience and force them to become more analytical.”3

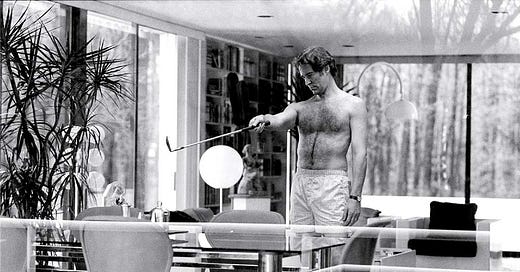

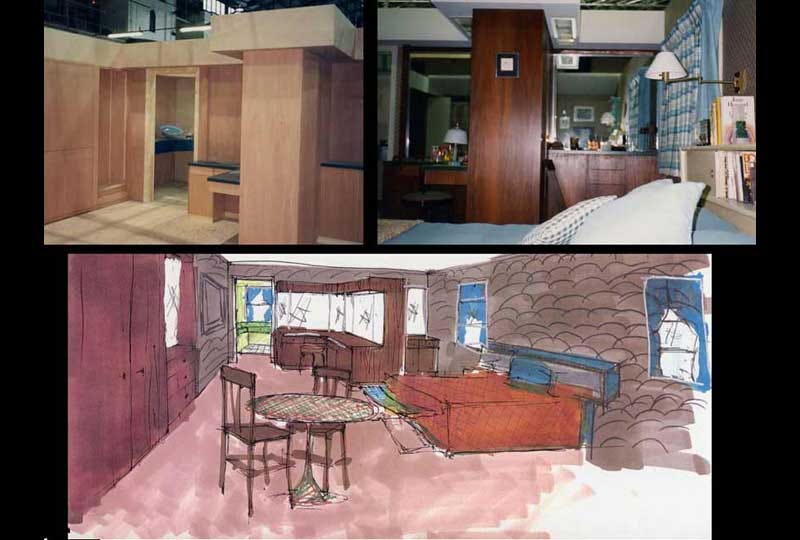

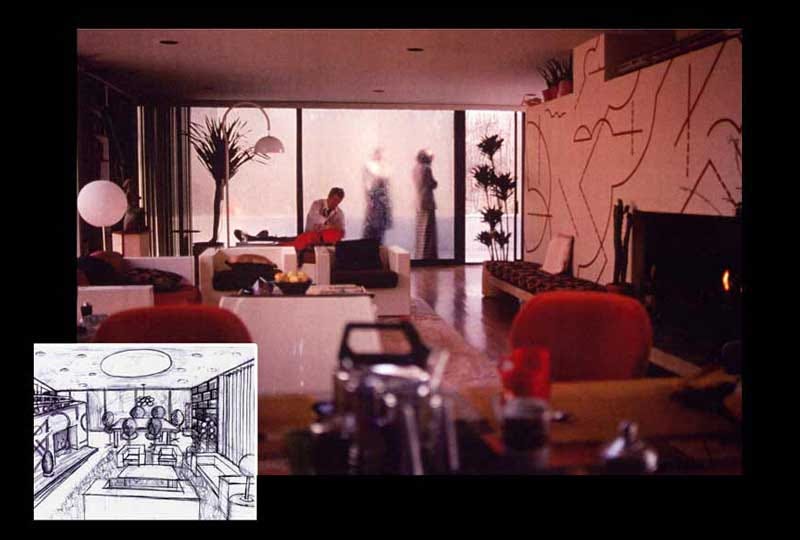

If you’ve watched the movie, you’ll know that the homes of the two central families are as much characters as their inhabitants. Elmes said that they “didn’t tie specific looks or lighting to characters, but we did establish their homes in a way that would say something about the people who lived there.”4 The Hood family (Kevin Kline, Joan Allen, Tobey Maguire and Christina Ricci) live in a 1950s mid-century home—a comfortable, warm space with lots of patterns and objects—while the Carver (Sigourney Weaver, Jamey Sheridan, Elijah Wood and Adam Hann-Byrd) abode is a starkly modern mostly-glass box. The “reflective material such as glass and metals” is keenly felt here, especially in contrast to the woods that enclose both buildings. For Elmes, he was aided by Friedberg’s design in “using reflections in windows, mirrors, and any other glass surfaces to add to our photo-realist approach, foreshadow the ice storm and represent the characters. We built translucent surfaces into the sets and even the practical locations, putting in pieces of glass to build up reflections, That also suggested the impression of looking through things and past the surface at something else.”5

Friedberg (who actually got his start as a production assistant on Woody Allen’s Another Woman and New York Stories), talks of the casting process for these homes as well as the location of the infamous “key party” in the clip below. The Hood and Carver houses were found in New Canaan, while the more traditional Colonial “key party” was filmed in Greenwich.

Filmed in the spring of 1996, a scant 23 years after the movie was supposed to take place, most of the crew were able to use their memories to situate the film. For Friedberg, “This was one of the first movies I researched in my own memory bank, as opposed to in books and magazines.”6 He even borrowed some props from his father’s Manhattan apartment to furnish the sets. A researcher, Jean Castelli, brought together summaries of period books (everything from the pop psychology of I’m O.K., You’re O.K. to Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique), magazine clippings, commercials, and more for Lee to learn from; these three-ring folders were also given to the cast, helping them understand all of the cultural forces affecting their character’s actions.

As the majority of filming was done on location in the often-cramped spaces of real homes, everything was planned out carefully in advance. Elmes and Lee filed many costume tests to examine a variety of different fabrics on the actors; “We also did some different things with makeup, and went out of our way to put characters next to each other in the tests to see what they might look like together. Mark Friedberg brought in big painted samples of wall colors to use as backgrounds.”7 After the first screening Lee supposedly told Friedberg, “Mark, it really looks good. It’s not the seventies, but it’s interesting.”8

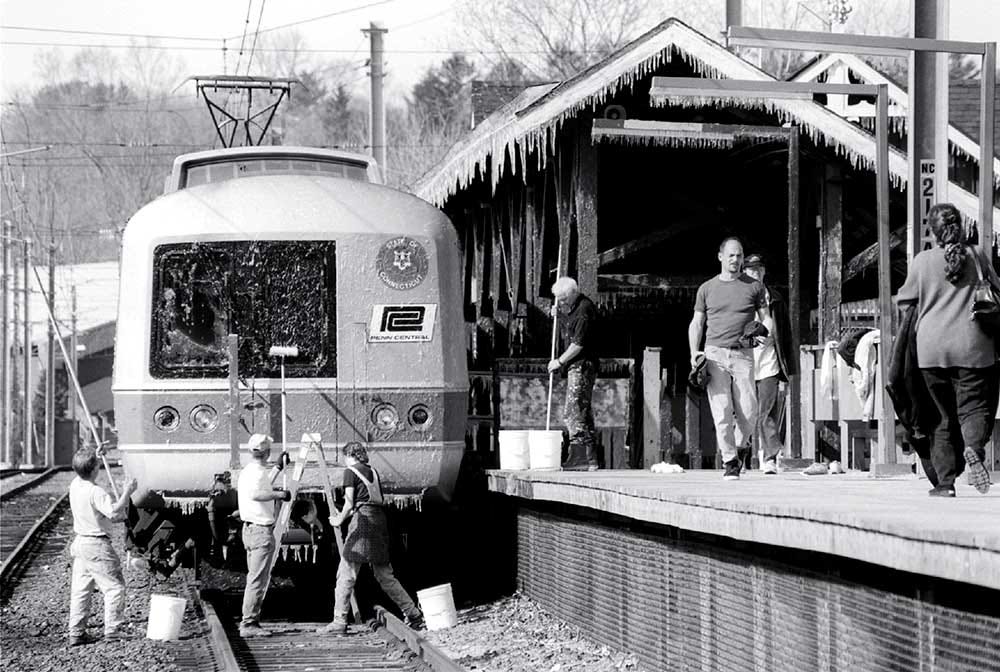

For the second half of the film, the team looked to impressionism for their inspiration in capturing the raw power of the ice storm. For Lee, “When I think of The Ice Storm, I think first of water and rain, of how it falls everywhere, seeps into everything, forms underground rivers, and helps to shape a landscape. And also, when calm, of how it forms a reflective surface, like glass, in which the world reappears. Then, as the temperature drops, what was only water freezes. Its structure can push iron away, it is so strong. Its pattern overthrows everything.”9 Complex experiments were undertaken to figure out how to capture the coldness, the ferocity, and the crystalline nature of the ice storm on film.

Not everyone liked the distance, even if they understood its purpose—critic Robert Sklar wrote in Cineaste of how Lee, Friedberg, Oditz and Elmes “re-created a 1973 world that Is cluttered with period things and styles, yet also feels harrowingly empty. Perhaps that’s one of the filmmaker’s points, that possessions in this social milieu possessed people: things filled the cupboard while souls starved. The effect is like an old photograph, in which we see evidence of past lives even though the people are no longer living. But film can shape a fiction that makes the past appear to live again, not, as in The Ice Storm, hold it at arm’s length and say, this frozen image is as close as we can get.”10 The mysterious motivations and emotional distance in the midst of such a richly observed setting may leave more unanswered questions than conclusions, but for those willing to delve in, The Ice Storm is a treat for anyone interested in the cultural dynamics and aesthetics of the 1970s.

David E. Williams, “Reflections on an Era,” American Cinematographer, October 1997, 56.

Bill Krohn, “The Ice Storm: Baby, It’s Cold Outside,” Criterion Collection, July 23, 2013.

Williams, 57.

Ibid, 58.

Ibid.

Frank Bruni, “In ‘The Ice Storm’…”, New York Times, September 21, 1997, 18.

Williams, 62.

Krohn.

Ang Lee, “Preface,” The Ice Storm: The Shooting Script (New York: Newmarket Press, 1997).

Robert Sklar, “The Ice Storm,” Cineaste, January 1997, 42.

Thanks for that exploration of a relationship between art and film, or art informing film.

I suggest another film similarly bound to its artistic mood board, although it's pop culture imagery and advertising that informs the look of 'The Loveless' (1981), Kathryn Bigelow's first film (co-directed with Monty Montgomery), which shows her brilliant future, although the film was not well received in the day. For me, it was an instant classic, and I learned every word of the dialogue in the '80s. I screened it the first year of my Motorcycle Film Festival in NYC (2013), and was happy to see how well the film held up, and how much better the audience 'got' it 30 years later - much more than when it came out! Time is kind to works of genius...