Richard Simmons III: Interiors for Sweatin'

Anatomy Asylum, Ruffage & Slimmons

Picking up from last week’s discussion of Richard Simmons’ early years and his jewelry line, an exploration of his establishments and their décor.

With a check in his pocket from a loyal Derrick’s customer, Richard Simmons set off in early 1975 to find a spot for his novel salad bar/gym concept.

Unlike recent decades, with salad bars—where one can put together their salad from different greens and an array of toppings—found at every cafeteria or luncheon spot, in the early 1970s they were the provenance of steak houses. While the true genesis of the salad bar is rather murky, with several restaurants around the country claiming to have been the first to install a salad bar in the 1950s and 60s, entrepreneur Norman Brinker is generally credited with popularizing the serve-yourself salad bar through his chain of Steak and Ale restaurants founded in 1966. Richard Melman took the idea and expanded out of steakhouses (and their more-paltry toppings) with his Chicago restaurant RJ Grunts in 1971, which offered more than forty ingredients—yet overall, salad bars were rare and known more for limp iceberg lettuce than interesting meals. So even in Los Angeles (then and now the health fad capital of the United States), one wouldn’t have been able to just grab a salad easily—either you went to a steakhouse to visit the salad bar or you had a sit-down meal in one of the few health food restaurants (say the Source Restaurant on the Sunset Strip, run by cult leader Father Yod), generally choosing a pre-planned salad from the menu. Simmons writes that he got the idea to open a salad bar on a visit to Chuck’s Steakhouse in Westwood, where “the salad bar was puny and hidden in a dark corner, like it was being punished.”

While driving around he encountered an empty Wilsons House of Suede warehouse on Little Santa Monica Boulevard (since renamed Civic Center Drive) in Beverly Hills. Long and narrow, “just like a dance studio,” it seemed to Richard the ideal location for a studio—in a more industrial part of an affluent area, it would be affordable yet close to the high-end shopping drags. According to Simmons, he called the landlord and “talked him into letting me have the space, which had already been leased.” Over the next few months, Richard and his team built out the restaurant and exercise studio, before opening in November 1975.

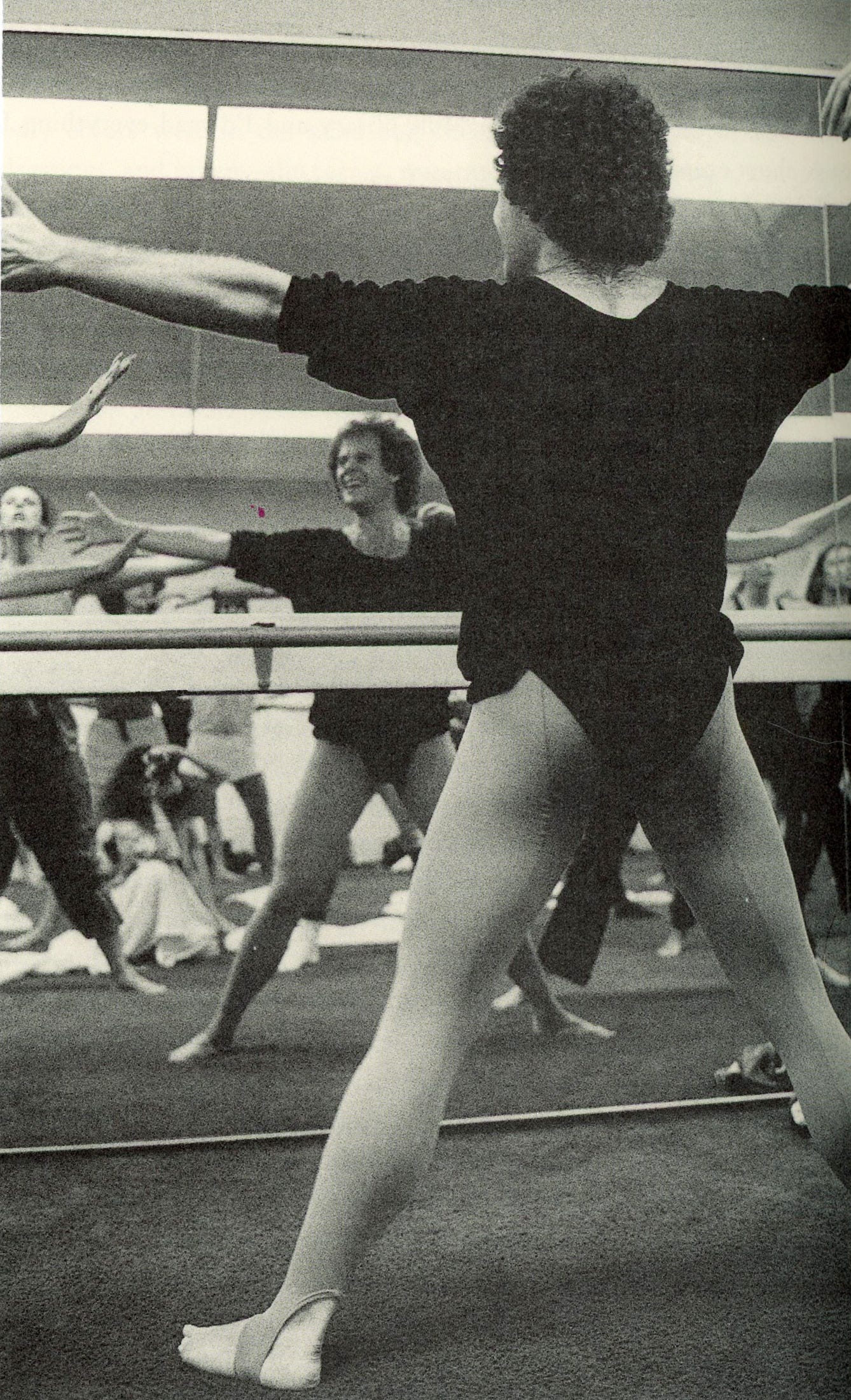

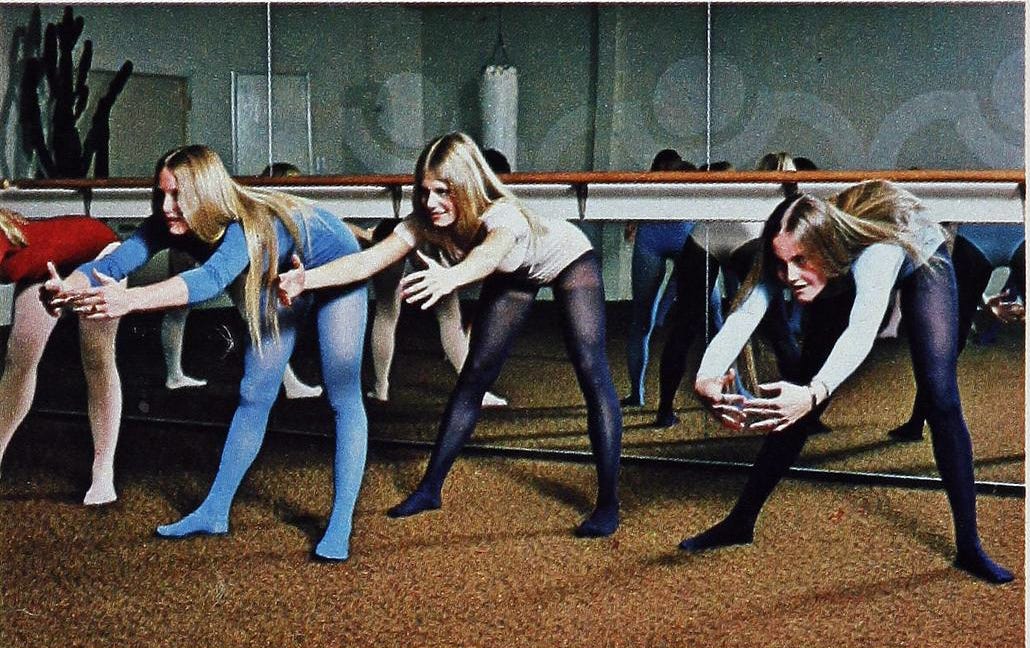

Anatomy Asylum was in the back—“Anatomy Asylum?! What kind of name is that? Well, if you’re a little crazy in the head, you go to the insane asylum. If you’re a little crazy in the body, you go to the anatomy asylum.” One length of the long room was completely mirrored with a mounted ballet barre; the opposite wall was painted white. Reminiscent of a paper doll chain, the Anatomy Asylum logo (an abstract human form with arms raised) was repeatedly painted large in optic white along that wall. The floor was covered in plush brown carpet, a common feature in exercise studios of the period. At one end hung a white leather punching bag, near a large cactus. While Simmons had hoped to replicate the live piano player he’d enjoyed at Gilda Marx’s class, it was beyond his budget—he settled for a record player and his favorite records. A separate white-and-mirror room was set up with Pilates equipment. Simmons brought on Kim Lee and Wanda Bouvier to teach Pilates there—both had trained under Ron Fletcher (one of Joseph Pilates’ proteges). The couple commissioned Kenny Endelman of Current Concepts to build their Pilates reformers to their specifications; Kenny would go on to found Balanced Body, Inc., still the leader in Pilates equipment.

At the front was Ruffage, Simmons’ salad bar. He hired hot young interior designer Charles Burke to create the space. Just starting his career, Burke was then-known for his “flair for designing clean, happy, whimsical rooms” (later to become more associated with a hedonistic disco-luxe aesthetic). Separating this salad bar from its competitors, Burke chose to make an all-white space—the opposite of dark wood paneled steakhouses or natural fiber-leaning health food restaurants. He covered the walls and ceiling in textured cement, all painted white, reminiscent of a room enveloped in frosting. White tile was laid on the floor, a 25-foot-long white wood-and-mirror bar installed along one wall and a curved drinks area and kitchen were built into one corner. Building tables out of Plexiglas topped with glass rounds, Burke made the space as light and bright as a cloud—even the white canvas-backed director’s chairs didn’t break up the bleached environs. The Ruffage logo—all swirling sans serif letters—hung large on one wall, white on white. “To give it that enchanted feeling, Charles took the white umbrellas you see in photography studios and hung them upside down from the ceiling.” Tubes of twinkle lights were arranged around the room to provide a soft glow. As Richard recalled, the only color came from the salad bar items (their bowls dropped into aluminum pans filled with curly kale). The whole effect of both spaces was clean, bright and inviting—by lightening up the rooms and not including any signifiers of working out (gleaming chrome weights and machines), the interior design proved to be a welcoming beacon for all types of people.

Anatomy Asylum and Ruffage immediately drew a crowd of celebs and socialites—and regular people desperate to change their bodies. Richard had been right about his guess that there were lots more people like who he used to be: “There were people who hadn’t thought that exercise could be fun. There were more people who’d never set foot in a gym or dance studio because they were embarrassed by their size. There were people who had harmed themselves trying to fit in and lose weight. I welcomed all of them into my studio.” Beginner exercisers stretched and danced next to models and actresses like Cheryl Tiegs and Rene Russo—all were welcome and accepted, no matter their size, ability, race, age, or gender. The classes weren’t cheap though—an introductory 10-class series cost $100 (taking into consideration inflation, today that would be $553 or $55 per class). After that, single classes were $4 ($22 in 2023). When asked how he could charge the same for 10 classes that it cost for a year membership to the Y, Simmons remarked, “It’s a matter of life-style. Some people like to buy a dress at Lerner’s. Some people prefer Bonwit’s. In our field, we’re the Bonwit’s.”

Ruffage was where one would find “the lunch bunch that watches its calories” (including Barbra Streisand, Joan Quinn, Sally Struthers, Tatum O’Neal, Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman), with the extensive contents of the salad bar widely celebrated as delicious and the décor equally as feted. Richard was as much of a draw as the food. “Wearing gray tights and a black tank suit top, Simmons… yells insults at the patrons, new and old, especially if he doesn’t approve of their eating habits; kisses the women and men with equal ardor, and keeps reminding everyone that he opened the restaurant ‘To make people healthy and make them laugh.’”

As Richard recalled in his memoir, Still Hungry After All These Years: My Story:

This was a typical day for me: I’d get up early, about 4 A.M., and I’d go to a wholesale produce company called Mushrooms, Incorporated, to buy all the fresh produce. I’d bring the produce back, and Roberta and Edna would begin their work while I went to teach the first exercise class at 6:30. After class, I’d join Edna and Roberta in the kitchen to help them prepare the food for the salad bar. Then, there’d be another exercise class at 9:00. After that, we’d set up the salad bar and prepare for the lunch crowd. Then there’d be an exercise class at noon. That’s when the salad bar would really start getting busy. Just after one o’clock, the noon class would come out and have lunch. I’d spend my time restocking, cleaning, and going from table to table. There were more classes at 4:00, 6:00, and finally 8:00.

Richard and another trainer Nina alternated teaching aerobics classes, while Kim Lee worked out the likes of Raquel Welch, Natalie Wood, and Cher on the reformer. Lee and Bouvier left to open their own studio in mid-1976.

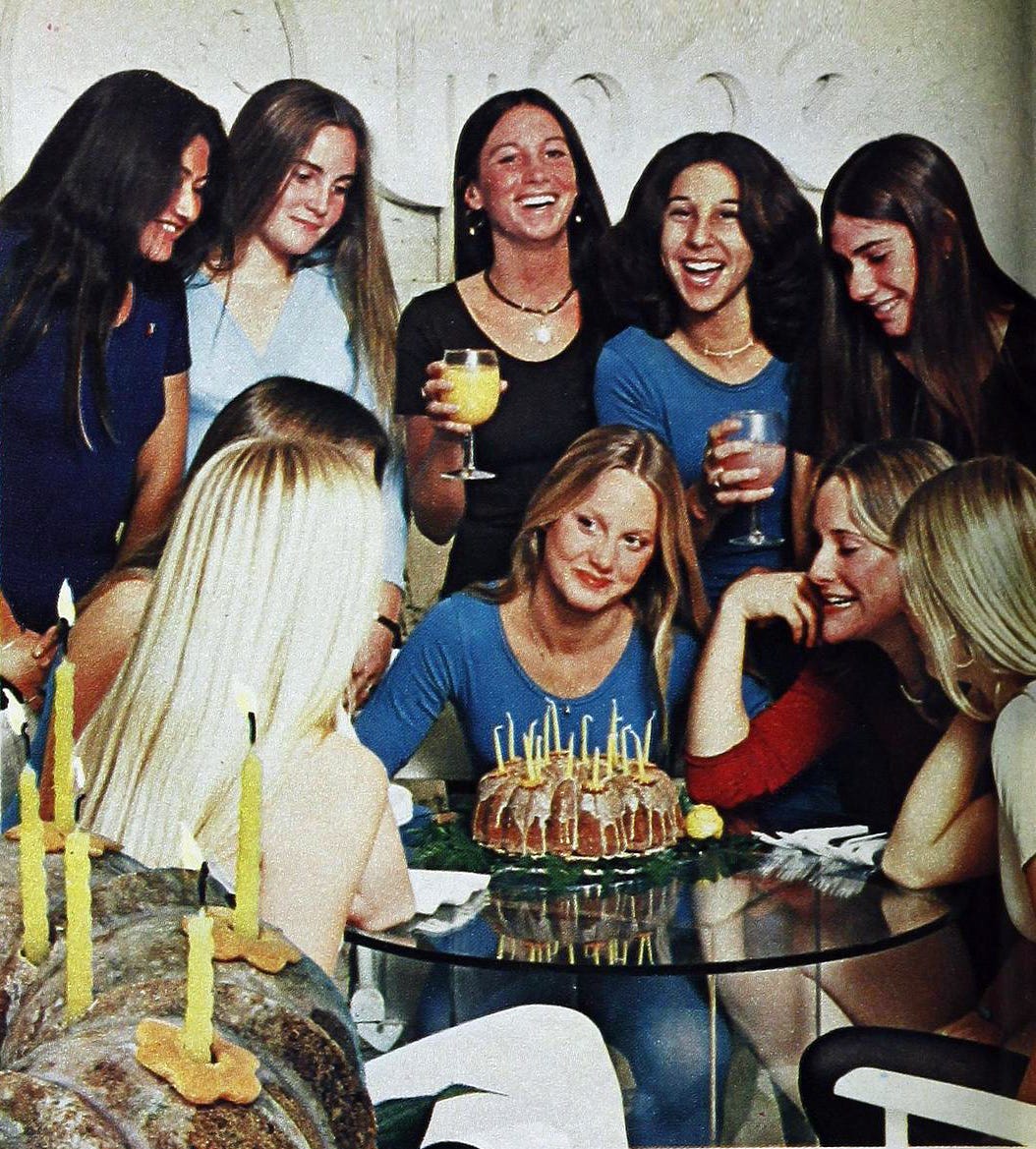

Among Simmons’ many offerings was the ability to hold stretch-and-salad parties in the space; each Friday and Saturday the Asylum closed early to allow for these private events. They ranged from the simple—like the sweet sixteen party he held for a Seventeen magazine shoot—to the very elaborate: “Richard Simmons’s Anatomy Asylum, a Beverly Hills gym where Bette Midler, Diana Ross, and Cher exercise to disco music, now caters parties at which hosts instruct their guests to arrive in exercise suits. The evening begins with a half-hour of yoga, followed by a break at the caviar, chicken, and shrimp-salad buffet. Then the party guests take a dancing class before ending the evening at the make-your-own-yogurt-sundae bar.”

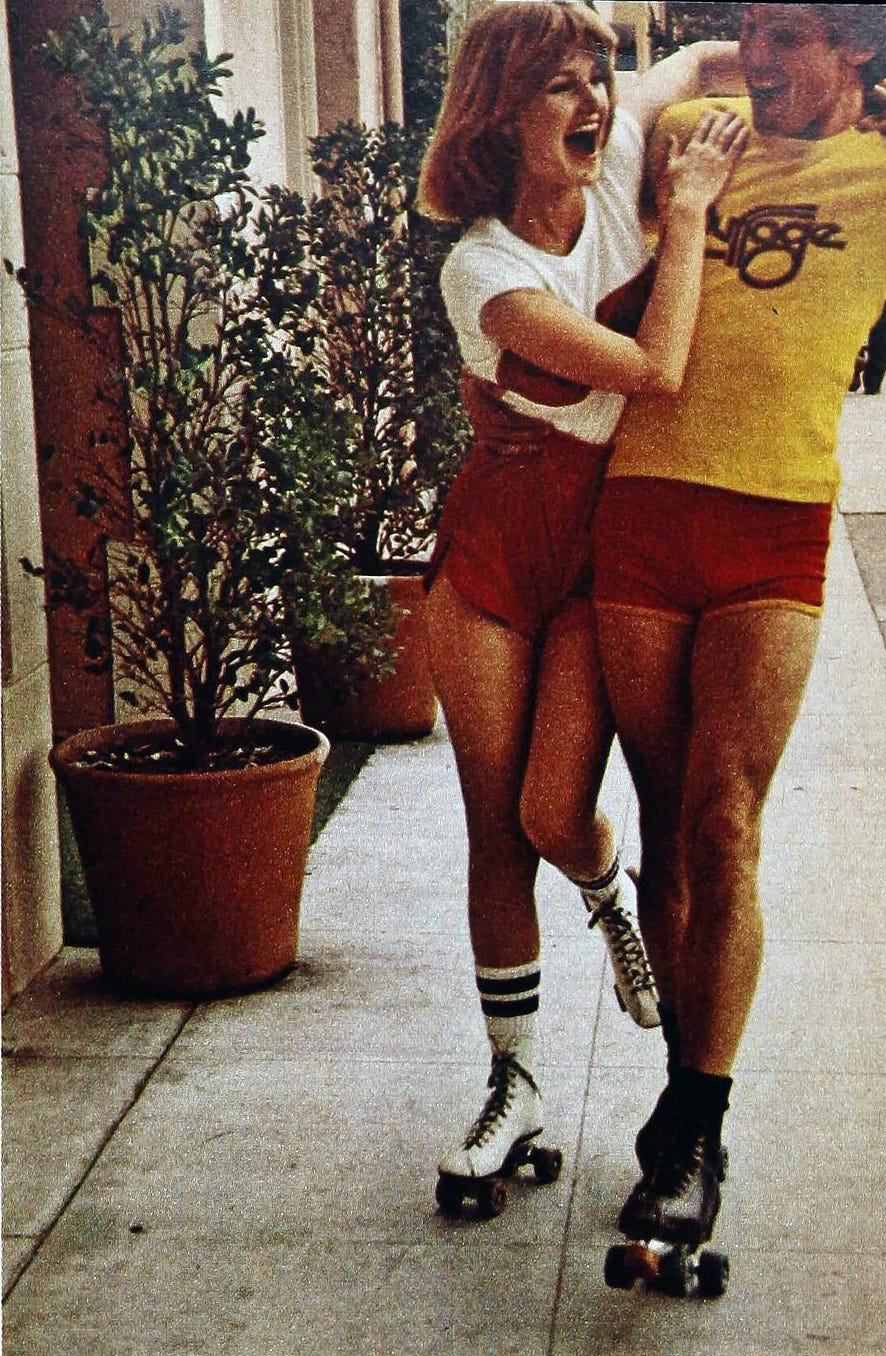

For the July 1978 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine, Richard produced a photo story on designing “your own health-weekend” with your partner—instead of spending the weekend with your lover drinking and carousing, the copy entreated readers to find fun in healthy ways. Using Ruffage, Anatomy Asylum and the home of Charles Burke (Ruffage designer) as locations, roller-skating, massages, baths, and jogging in place were among the suggestions for a romantic, non-hedonistic date. Richard even popped in for a cameo behind the drinks bar at Ruffage, providing healthy eating advice.

The success of Ruffage led to them opening an outpost at I. Magnin’s downtown Los Angeles store in November 1978, though it appears to have been a move taken by Simmons’ business partner. Simmons told the Los Angeles Times that he did not want to be involved, adding, “They’re doing what I don’t believe in. I would never serve a hamburger in a restaurant. I would never serve a blueberry muffin with lots of butter. So I’m staying clear of it.” He frankly also didn’t have the time—he’d started appearing on local news and talk shows, on which he taught exercise segments, which quickly gained him quite a bit of attention and precipitated a diet book deal. By 1979 Simmons was appearing as himself in a recurring role on the long-running soap General Hospital, where he taught aerobics to the nurses during their breaks. In between filming General Hospital and leading classes at his gym, Richard took to traveling the country and visiting a new mall each weekend, where to oldies like “The Locomotion” and “It’s My Party” he led crowds of adoring fans in stretching, dancing and sweating. Richard was officially a star.

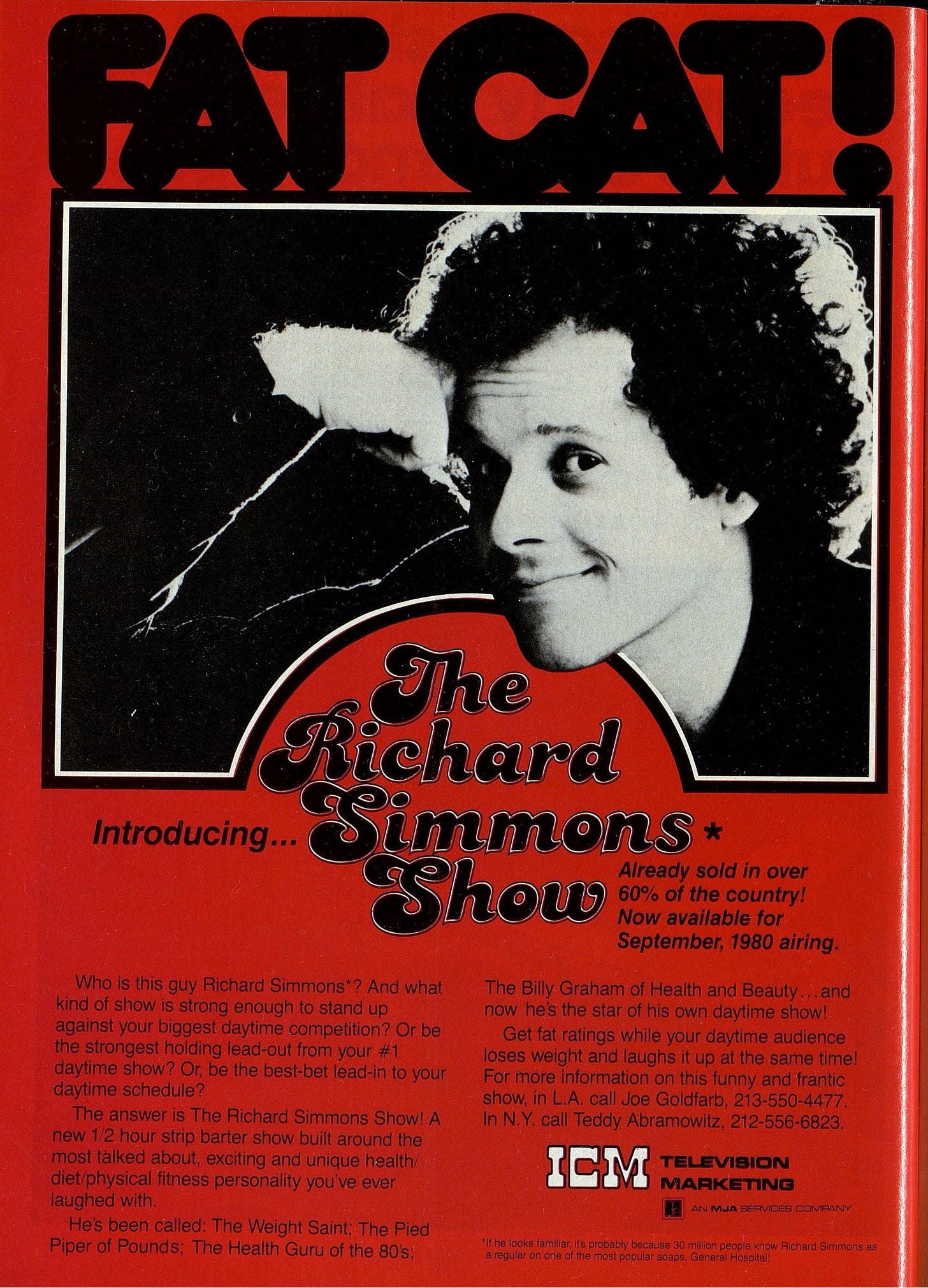

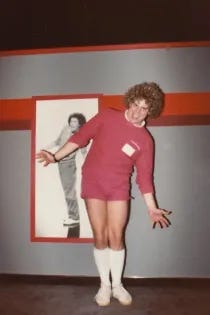

The Richard Simmons Show premiered in September 1980. Described as the “Billy Graham of Health and Beauty” (this comparison to the famous televangelist recalling his childhood dreams of the priesthood), Simmons’ half-hour program was a sort of exercise variety show—combining talk show segments with workouts and skits. Filmed at the KTLA studios in LA, the set was surprisingly subtle for someone as colorful as Richard. The large studio featured two stepped platforms, completely covered in beige carpet—one left bare for chats and workouts, the other featuring a beige-and-tan living room set—all backed with diagonal pale wood laminate panels alternated with mirror. For cooking up healthy meals onscreen, there was a beige kitchen, featuring a fake window looking onto a faux garden, lavishly filled with plants. The effect is basement rec room, school multi-purpose room—a non-threatening space where Richard could teach, charm, and bully (viewed in 2023, his language is often shockingly fatphobic) the leotard-clad audience.

Realizing that he was stretched too thin, by mid-81, Simmons had closed Ruffage—renovating the whole space into an expanded exercise studio. As exercise was understandably his main focus—and with his show broadcast in markets nationwide and the ability to pull massive crowds at any random mall—the next step for Richard was to make Anatomy Asylum into a chain. He signed a deal with Bally in 1982, resulting in a flurry of openings across the country. By the end of 1982, there were seven locations in Los Angeles and Orange County, along with several gyms in the Atlanta and Chicago areas; Boston followed in 1983. Commonly located in shopping malls and centers, the décor of these health clubs appears to have been unregulated and inconsistent; very few photos seem to survive (if you have any, please send them my way!), but those I’ve found include such diverse design choices as cloud-and-rainbow wallpaper, drab gray walls, and lots of wood paneling—the antithesis of the bright, clean aesthetic of the original. Simmons frequently visited the gyms (I counted 34 different clubs, though there were likely more), helping to train staff and teach aerobics and nutrition.

Simmons likely kept his original location separate from the deal with Bally; though included in ads for Anatomy Asylum gyms, he maintained control of it—and around 1985, renamed it “Slimmons.” Richard continued to teach at Slimmons until his “disappearance” in 2014; he has not been seen in public since then. Much has been discussed around his choice to retreat from the public eye, with copious conspiracies thrown about—the podcast Missing Richard Simmons (2017) brought global attention to these questions and has been followed up more recently with a TMZ documentary What Really Happened to Richard Simmons (2022). Regardless of Richard’s reasons for choosing a completely private life, his pulling back from teaching classes had a direct effect on Slimmons—slowly fewer and fewer people turned up to exercise with the studio described as being “in a sad state” and in need of “a major makeover!"

While I have been unable to find any 1980s and 90s photos of the Slimmons’ interior, by 2016 it was shabby and appeared to have last been updated in the late nineties; during a period when boutique fitness was growing exponentially with studios becoming increasingly sleek and glamorous, Slimmons was out of step with the aesthetic and kinetic trends. As one longtime fan (who lost 160 pounds with Richard’s help) described it, “It all happens in a standard, no-frills room. Despite its Beverly Hills address, Slimmons isn’t a state-of-the-art facility or an architectural marvel. It doesn’t even have air conditioning… If the small lobby wasn’t full of Richard photos and merchandise, you’d never think this place was run by one of the world’s most iconic fitness personalities.”

Mirrors lined the long walls of the narrow exercise studio, with a mounted barre on one side (seemingly the original from the Anatomy Asylum). Instead of white, a pastel color palette dominates: the ceiling painted a peachy-beige with structural supports in mint and peach, the front wall mint, the back peach. A single disco ball hangs in the center of the room. The former Ruffage space had been converted into a shop and waiting area—three walls mint, the last peach—covered in photos of Richard and memorabilia for sale. Hanging from the ceiling were white Japanese paper parasols, reminiscent of the white photo umbrellas Burke hung in Ruffage. Beige doors, beige cabinets and nondescript chairs complete the rather drab interior. RadarOnline visited in March 2016 and spoke with a Simmons’ insider, who called it “a ghost town.”

The final class was held at Slimmons on November 19, 2016. Following its closure, the space became another gym for a few years before being converted into an office space.

In my paid subscriber newsletter this weekend, I will be finishing up this series with a discussion of Simmons’ incursion into plus-size activewear.

.