Months ago, I came across a mention of a Richard Simmons clothing line, the first athleticwear for what we now call “plus size” women, in a 1980s newspaper and marked it as a subject to return to. Once I started doing background research on it, it became clear that first I needed to discuss the early years of his fitness career (and his brief forays into fashion before it). As someone interested in fitness history and the rise of gyms as fashionable gathering places, Richard Simmons and the Anatomy Asylum was too good a topic to pass by. I’ve expanded this into a four-part series: Simmons' life up until 1975; his 1972 jewelry line; the design of his first gym, Anatomy Asylum; and his 1980s “plus size” activewear line. This first article functions more like a normal biography (while pointing out the inconsistencies in his autobiographies and biographies), while the others hone in on specific moments in his career that are directly related to fashion and design.

When we think of Richard, we think of the caricature he created—the irrepressible, madcap instructor in tiny shorts and with a frizzy halo of hair, the motivational screeching over oldies—as well as the questions regarding his whereabouts and safety (he has not been seen in public since 2014). The incredibly public person who spilled all the details of his childhood obesity and eating disorders on national TV and who turned up for his Slimmons’ classes for decades, a friend to all—yet who was unknown by everyone. This isn’t a piece attempting to decipher the intricacies of his psychological makeup, but one about how he came to become a gym owner for the elite and then parlayed that into nationwide fame.

I spent a long time sorting through and writing about the inconsistencies in Richard’s stories of his late teens and early twenties. Repeating these stories over decades, the timelines and events expand and contract and shift—what appears to be the truth is directly contradicted in a later interview. Memory is inherently fallible and exaggeration tempting, but the continuous irregularities gave me pause. There were larger events he spoke of often (like his trip to Italy) that I could find no proof of beyond Richard’s tales—with him providing many varied reasons for it (med school, art school, foreign exchange student) and many different jobs had while there (“fat model,” Fellini extra, star of commercials, fashion illustrator) in a seemingly brief time-frame, the veracity of much of his narration came into question; even his 1999 memoir, Still Hungry After All These Years: My Story, proved to retain this pattern of irregularities (for example, giving multiple different dates for one event). With Simmons, facts and memories are fluid—Richard Simmons’ has been in a continual state of self-creation since the late 1960s.

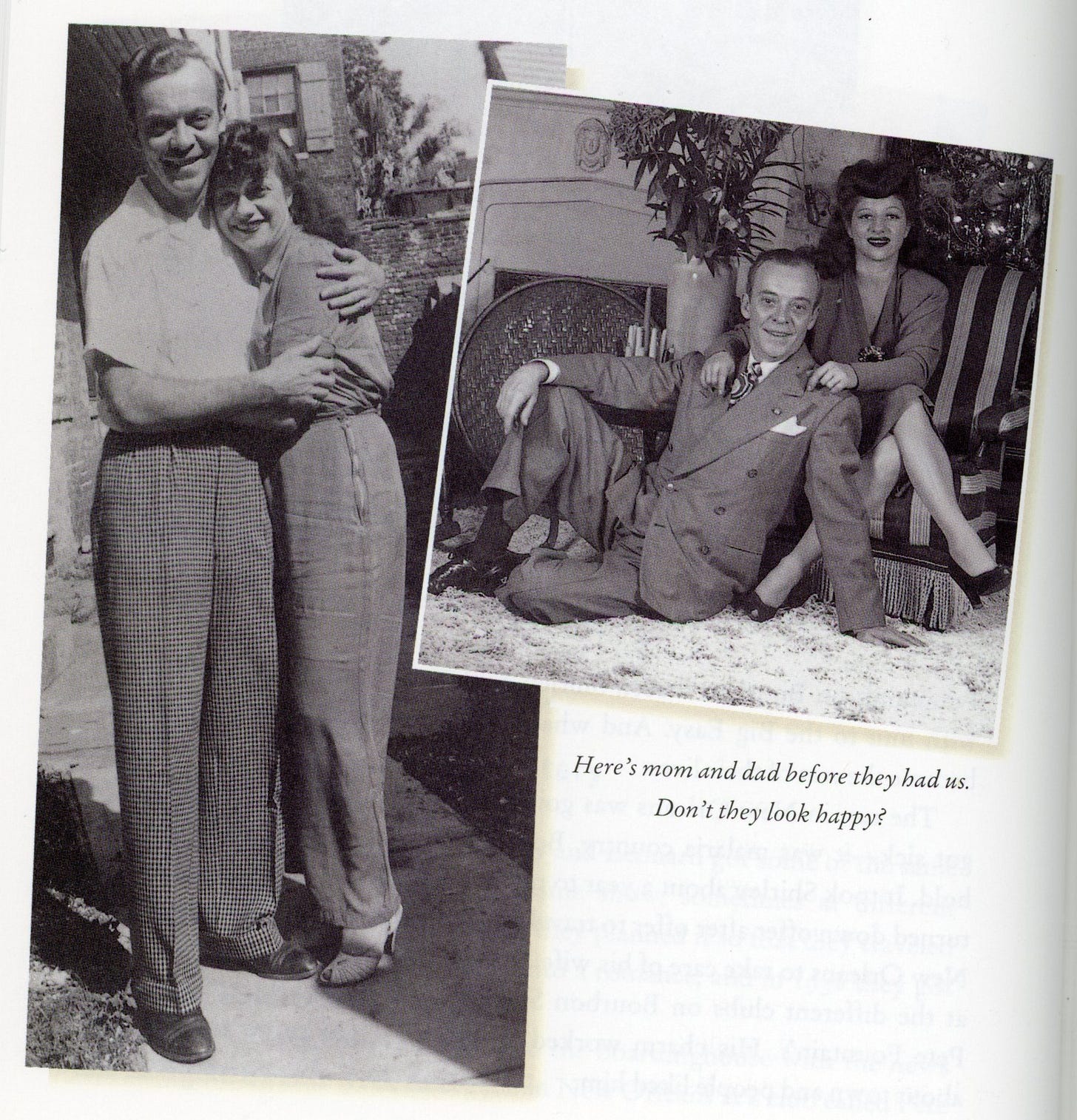

Born in New Orleans in 1948 to former vaudevillians (according to his memoir, his father was a singer/dancer/MC turned SAHD and his mother a fan dancer turned cosmetics seller), from childhood Milton Teagle Simmons was in a constant battle with his father. With food standing in for love in his family, he sought solace in the rich treats that New Orleans is so known for.

Uncomfortable and unhappy with his weight, Simmons later spoke of how he bathed in the dark as a child and teen. After his parents placed him in a local Catholic school, he found comfort in religion. Some post-fame interviews state that Richard did not discover he was Jewish until he was sixteen or nineteen, while others say he always knew his mother was a Jew and his father Methodist—he rejected both and was baptized at twelve or sixteen. According to some interviews, after high school, he briefly entered a Dominican seminary in Iowa (if true, likely the Aquinas Institute of Theology in Dubuque) to become a priest—supposedly staying there anywhere from a few months to two years. “It wasn’t for me, it just wasn’t for me,” he said in 1984. “But, see, as a child I thought the two most important things you could be in life were a doctor or priest because they got so much respect and love and they saved lives and they saved souls.” Alternately, in his memoir, he states that he only went to a meeting at a local monastery following a high school career day before choosing to study art at the University of Southern Louisiana. After two years he transferred to Florida State University, as they offered exchange programs with schools in Europe.

Simmons’ time in Italy is part of his creation myth—told and retold in interview after interview, subtly changing and evolving, yet always of great importance. While in his memoir, Simmons asserts that he arrived in Florence in January 1968 as an art student, in other places he speaks of going to medical school there or working as a fashion illustrator. As an art student, he took Aubrey Beardsley as his stylistic inspiration. While in Italy, he allegedly met Federico Fellini in a pizza parlor or met Fellini’s casting director at a cafe. At his highest weight of 268 pounds and with long curls framing his round face, they thought Simmons ideal for a background role in Fellini’s 1969 adaptation of Petronius’ Satyricon. In articles and on Youtube, a musician in the film is singled out as Simmons—it is Francesco Di Giacomo, the lead singer of the Italian prog rock band Banco del Mutuo Soccorso. Simmons writes in Still Hungry that he was simply in the “Tower of Babel” crowd scene. I’ve yet to find Richard in either Fellini film (Satyricon and The Clown) he is said to have appeared in, but both have many scenes with vast numbers of costumed extras—Simmons could easily be in either/ both or he could have chosen these films to weave a story around for that exact reason. No photographs are included in his memoir from 1966-74 to back up any of his claims.

According to a 1982 Harper’s Bazaar interview, Simmons parlayed being a Fellini extra into acting in Italian commercials, including dancing hamburger (or meatball) for a fast-food chain, and modeling in ad campaigns, such as one for “Luv Boy” husky jeans. “The Italians really loved me. To them I was a cute, chubby, curly-headed Botticelli angel!” One day he came back to his car and found an anonymous note (scrawled on his windshield or tucked under a wiper) that read: “Dear Richard, Fat people die young. Please don’t die.” Apocryphal or true, this story is widely disseminated as the defining moment in Simmons’ young life. Devastated by the note, he went on a crash diet that helped him lose over a hundred pounds in a very short amount of time.

In a late 1980s Oprah interview (below), Richard said he lost 123 lbs. at age 19 and more the following year—getting down to 119 lbs. at his lowest, leading to hospitalization for anorexia. This timeline does not match that of his Italian Fellini sojourn, as Simmons turned 20 at the time of Satyricon’s production. In September 1972, he told a reporter that he has just lost those 123 pounds two months previously. Regardless of when between 1969 and 1972 this took place, Richard used starvation, diet pills, and purging to slim down dramatically. His weight loss and malnutrition were so quick and intense that he supposedly lost his hair (requiring a hair transplant) and needed a full facelift due to sagging skin—this was quoted as costing $13,000, which if done in 1971 would be over $95,000 today.

When his number came up in the December 1, 1969 draft lottery, Richard returned to America—skinny, ill, and with a fabulous new wardrobe (flying home in Swiss lederhosen and a suede maxi-coat). Excused from military service due to the effects of malnutrition, he settled in New York—trying to get work as a commercial artist, before taking a job as a waiter at the car-themed restaurant, AutoPub. Located in the General Motors building, it was a sceney place with antique cars as booths. In addition to learning about bulimia from a fellow server, there Simmons also discovered that his flair for comedy and friendliness was a boon to his career. A regular customer hired him to work as a traveling beauty salesman, for Coty and Dina Merrill cosmetics (following in his mother’s footsteps). By the summer of 1972, Richard Simmons had left that job and was living in LA. Trying out different things, he launched a line of jewelry (more on that this weekend).

After seeing a classified in The Hollywood Reporter for a “waiter with a fun personality,” Simmons went straight over to the Beverly Comstock Hotel on Wilshire Boulevard, where on the second floor a new restaurant had just opened. Derrick’s was the dream of Derrick (a Welsh chef) and Judy Thomas (the Irish host); Simmons described it as a “little gem of a restaurant…There were twelve round tables. All the seats were deep maroon vinyl and each table was lit by candlelight. The walls were dark wood paneling, giving the place a cozy feel.” He slotted right in, just the three of them plus a barman running the little Italian restaurant. Good reviews (“It is a good, lively, highly individual restaurant and I recommend it to the chi-chi and the non-chi-chi alike”) and word of mouth quickly brought in the crowds, with Richard gaining as much of a following as the food. The Los Angeles Times remarked how Judy was assisted by “an effervescent catalyst named Richard Simmons, who came out in the hall to reroute us when we missed the entrance, sat down to explain the menu, was delighted to advise, and kissed me when we returned.” In his memoir, Simmons said this review led to a three-hour wait to get in for dinner but also provoked resentment among the Thomas’ for their star waiter. Los Angeles historian Alison Martino writes that Derrick’s regulars included “Henry Mancini, Sidney Poitier, Johnny Carson, Joe Cocker (who was living there at the time), and Ed McMahon and Johnny Carson who brought a host of celebrities and fun people who closed the place down nightly.” Martino’s parents (her father was crooner Al Martino) also visited often; she recalls that Richard “would also insult the customers in a humorous way. It was all in fun until he cut your tie off! (He cut my fathers off once and I started cry!)”

Surrounded by free food, Richard took to jumping on every LA diet fad, from Ex-Lax to juice cleanses and HCG injections, and every exercise trend, from yoga (with Bikram Choudhury himself) to pilates and weightlifting. A customer brought him to Gilda Marx’s aerobics class (the grande dame and progenitor of the movement), a truly life-changing moment: “I couldn’t remember a happier day than when I’d taken that class. It was the first time I felt that my body was alive.” While a man played the piano, Gilda led the class in dance aerobics: “We cracked jokes together as we danced, and maybe I did sing a number or two. Exercise could be fun…” Though he paid for a series of classes, that night Gilda turned up at Derrick’s to tell Richard that he was no longer welcome and would be refunded—she alleged that the women in the class felt uncomfortable with a man there, but Richard later wrote that he was “too much of a cutup, too much of a disruption for her to handle.”

Desolate, he slowly developed an idea for his own exercise studio—where everyone, of any size or gender, was welcome. Folding in a concept for a salad bar (at the time solely the domain of steakhouses), Richard received funding from one of his Derrick’s customers, clothing manufacturer David Weisman. He spent the summer of 1975 driving around Beverly Hills looking for open locations.

More on Anatomy Asylum and Ruffage next week.