Welcome to all new subscribers! Please go back through and enjoy the archive, visit my Instagram (where I am always posting images and films from my research), and consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work and receive all newsletters.

I try to send out two newsletters a week—one free and one paid—but my schedule doesn’t always provide me the time to research and write so much. As I’m deep in finishing up (editing and fact-checking) two large projects, my newsletter today is an article on Romeo Gigli’s artistic inspirations I wrote a few years ago for Heroine—the sister site for Grailed, it was shut down in 2021 so I’m rescuing this from the mists of the internet. I am working on a longer piece that will be sent out to paid subscribers later this week.

The Artistic Reveries of Romeo Gigli

As a fashion designer, Romeo Gigli’s designs in the 1980s and 90s were steeped in an artistic sensibility that intimately revealed his evolving influences. The son (and grandson) of an antiquarian book dealer and a contessa, Gigli brought to his clothes a cultured, nuanced expression of different artistic epochs heavily influenced by the refined milieu of his parents. At the peak of his fame in 1988, he said, “In my father’s library I saw all sorts of art, representations of women throughout history. I translate what I have seen for contemporary times.”1 His references were rarely literal, instead veering towards the emotional—rather than having a fabric printed with a painting or replicating the clothes in a portrait, Gigli instead worked to recreate the emotion brought forth by a piece of art: the somberness of abstract expressionism, the romantic vulnerability of a pre-Raphaelite beauty, the spiritual ecstasy of Byzantine mosaics.

When Gigli was 18 his parents both died within ten months of each other, leading him to drop out of his architecture studies at university and start roaming the Earth; selling off his father’s treasured books as needed and collecting the interesting things that crossed his path (most often textiles and costumes). Styling himself in these items, his completely individual look drew attention when he finally landed in New York in 1977—where he was asked to consult by the custom tailor Piero Dimitri. Once back in Italy he worked for Gianfranco Ferré before launching his own collection independently for autumn/winter 1983. Attracting immediate attention, the press described Gigli’s designs as “minimalist sportswear”—simple, stark shapes in black and muted tones with an almost monastic quality to them. A partnership with Carla Sozzani and her husband provided him with the resources to expand his collection for international sales in 1985. These early shows were often compared to the intellectually rigorous designs emerging from Japan at the time, yet when Romeo Gigli was asked for his favorite designer he answered “Frank Lloyd Wright”2—Gigli using his earlier studies to morph modern architecture’s severity of line into fashion form.

As he refined his message, several vastly differing seeds of artistic influence began to emerge within the same collections—blending to create a specific elegiac mood and somber elegance. In 1986, at a time when Christian Lacroix was bringing an over-the-top luxury reminiscent of Marie Antoinette to high fashion, Gigli’s dirndl skirts and bulky over-garments instead recalled the nineteenth-century French peasants depicted by Realist painters such as Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet. Drawing not just on the silhouettes, he also took inspiration from the color palette and textures—the soft earth tones with flashes of red and blue (as vividly seen in Millet’s “Woman baking bread” from 1854) while Gigli’s favored crinkled gauze and stretch linens were a modern updating on harsh burlaps. Romeo Gigli’s design characteristics that so captivated the critics—an ease of movement, the sense that they did not impose an identity on the wearer—are simply a modern stylization of the tenets of peasant dress (egalitarian, built for hard work and wear). At the same time, his designs increasingly became about a balance between the sensuous and the strict—a cloud of blood red organza floating weightlessly from beneath a black knit shroud, oversized sweaters paired with earth-toned wool crepe skirts. The color palette and combination of tones (clay and earth, eggplant and black dark gray with the occasional blast of red) reflected an interest in the work of abstract expressionists like Mark Rothko (particularly as seen in his Seagram Murals from 1958).

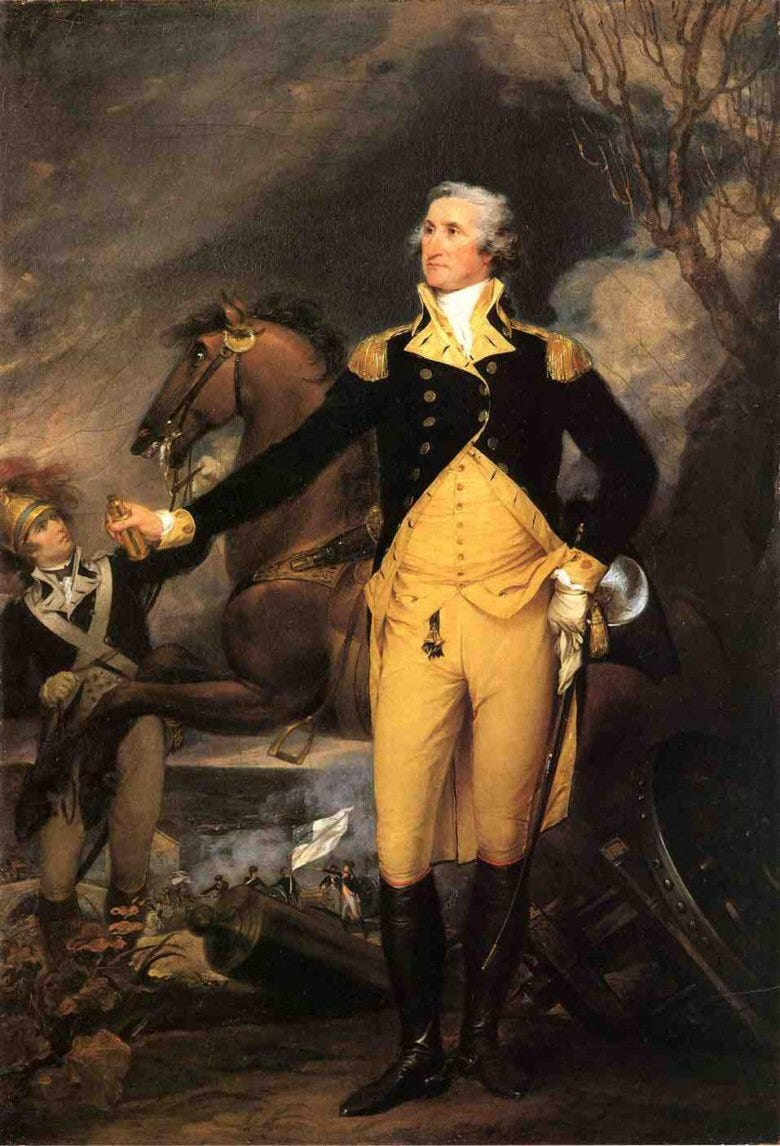

Most prevalent was the pseudo-medieval feeling of the Pre-Raphaelites, found (again) in the colors as well as in the high waists and low necklines of his collections from 1987 onwards. Cutouts necklines edged in lace with a rounded, cocoon skirt (which Gigli described as “heart-shaped”) molded out of soft chiffons, crepes and voiles (elasticized so he could forgo any inner structure or seaming) conjured a romantic mood little seen since the time of Gabriel Rossetti. Throughout his whole career, Gigli showed his collections on very pale, fragile-looking waifs—makeup-less except for a rosebud mouth, hair a mass of falling tendrils—whose slender shapes in either oversized or body-hugging clothes further emphasized his romanticism. This approach was also used in his crafting of more tailored garments. Even when designing garments that seemed more straightforwardly historic (a cutaway frock coat that appears straight out of an 18th-century portrait, for example), they were formed in a painterly, almost abstract way—while his contemporary Vivienne Westwood studied surviving patterns and garments, Gigli was less concerned with following the original seams and instead strove to suggest the simplified forms made by paint on canvas.

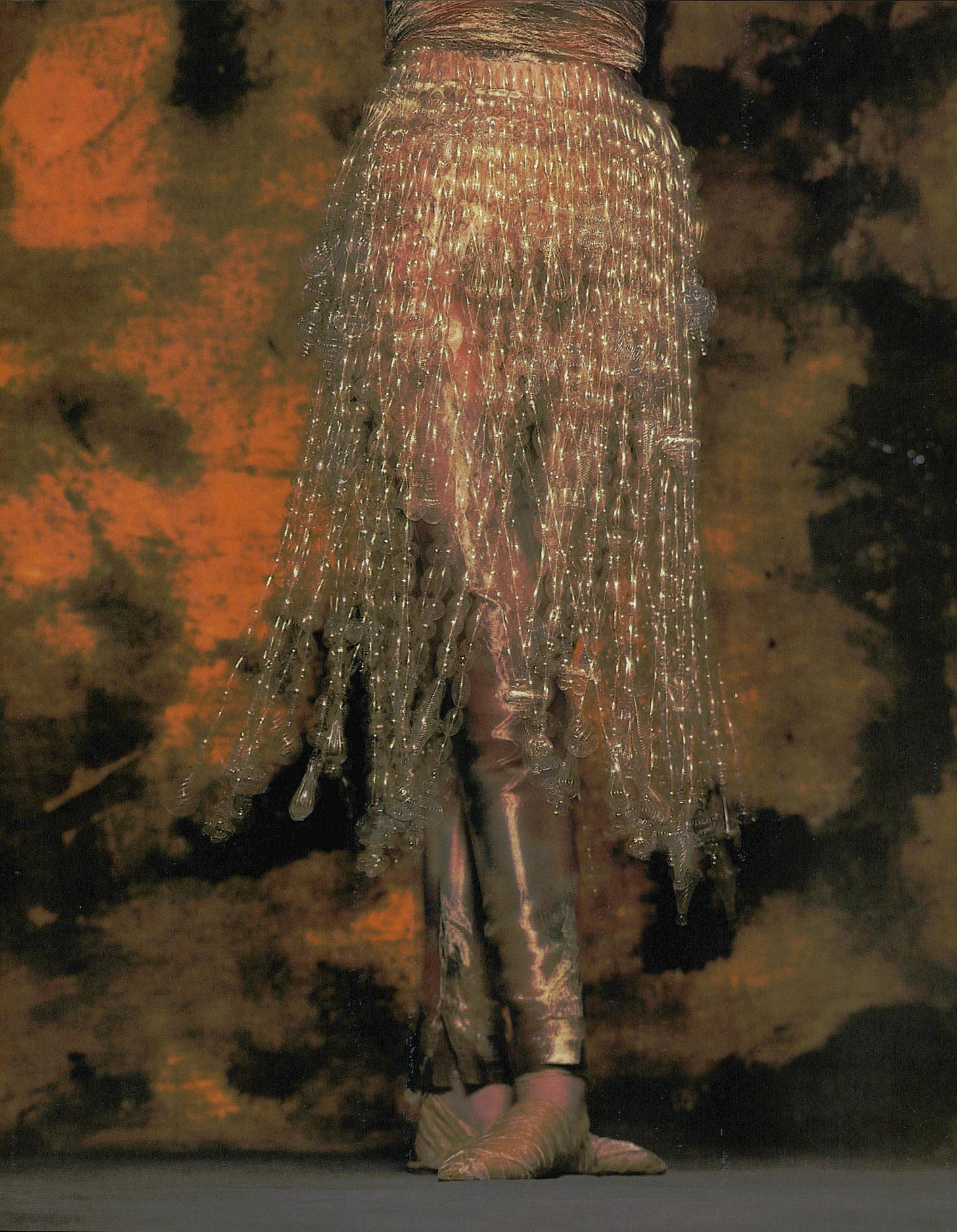

Starting with spring/summer 1987, Gigli was named head designer at Callaghan, which became another outlet for his exploration of these ideals. Both the Callaghan and Romeo Gigli collections built and played off each other—blending together a pre-Raphaelite pathos with Indian, Turkish and Persian elements discovered on his travels (Gigli continued to take large-scale adventures every year for inspiration). In keeping with his antiquarian lineage, much of the art he sought out was ancient—Roman and Byzantine in particular. As a child his parents had taken him to see Pompeii and the design of one villa became etched on his consciousness—“Its essential lines had communicated a serenity and profound interior elegance for so many centuries”—so when Gigli began designing he knew he wanted to put “the same enduring purity” into the lines of his clothes.3 His models for spring/ summer 1989 were compared to “bas reliefs from an antique Roman fresco” with their loose chignons wrapped in gold ribbons and the smudgy, clingy clothes.4 Taking Empress Theodora as his inspiration for fall/winter 1989, in Gigli’s hands Byzantine mosaics became gauzy gold lightly wrapped around the body and head; a cocoon coat heavily hand-embroidered with gold thread; gilded metallic leggings beneath a floating chiffon skirt and lace one-shoulder top. The former-Byzantine province of Venice was the inspiration behind the glass fringes used by Gigli for spring/summer 1990—a poetic gesture bringing a millennia of history into the new decade.

Though at the turn of the decade many journalists thought Romeo Gigli would be “the designer of the 1990s”, poor business dealings and changing styles resulted in him losing his high place in the firmament of Italian fashion. Gigli kept control of his company after a protracted court battle with his business partners, Sozzani and Donato Maino, in 1991 (losing his Milanese headquarters and store, which Sozzani quickly made over into the now-iconic 10 Corso Como), yet was shouldered with a crippling debt that left him perpetually at the behest of creditors and ever-changing corporations. Primarily since then, he has done small collections (under his own name when possible), consulted and taught fashion students in Milan. While over 25 years have gone by since he was the toast of fashion week, Gigli’s influence can be clearly seen. In 1990 a young Alexander McQueen was a design assistant for Romeo—later taking from Gigli the ability to create a poetic mood through the use of luxurious fabrics, romantic models and somber presentations. Dries van Noten most closely shares affinities with Gigli, as both bring to their work a certain academic rigor grounded in art history and a passion of textiles. Gigli’s influences—and his atmospheric methods of incorporating his influences – have gone on to inspire subsequent designers: Valentino under Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pierpaolo Piccioli looked to the pre-Raphaelites for fall 2014 couture and to Byzantium for spring 2016 couture, while Karl Lagerfeld’s pre-fall 2011 collection for Chanel also had a Byzantine theme. With an emotive atmosphere so palpable—and so inspirational to other designers—in Gigli’s designs, it is of little wonder that the Los Angeles Times remarked in 1988: “If poems could talk, they would say ‘Romeo Gigli.’”5

Bettijane Levine, “East and West: Designers Share Dramatic Views,” Los Angeles Times, December 16, 1988.

Bernadine Morris, “A Quiet New Talent At Milan Showings,” New York Times, March 12, 1986.

Levine.

Pat McColl, “In Milan, It’s Down to Earth With Ethnic Undercurrents,” Los Angeles Times, October 4, 1988.

McColl.

And, his menswear! I loved his color palette especially, rich hues of orange and purple, simple and structured in a very 80s sensibility, big pleats on pants and short collars with roomy shoulders on shirts. What I was able to buy(!) was not so romantic as the women's collections, but the tailoring was terrific.

I hadn't heard the connection with Sozzani; 10 Corso Como is a longtime fave, I even stayed there once, you can (could?) rent a room above the restaurant. That was a swank experience, although the neighborhood is really developed now and full of tourists. It used to be a curious dead end in Milan, now it's dead center.