Ozbek's Odyssey

Hello from Los Angeles! I completed two large projects over the weekend and flew out here yesterday morning—this week I’ll be doing a few interviews for my podcast, Sighs & Whispers, which has been on a little hiatus. I have several interviews already completed that I just need to edit, so hopefully in 2-3 weeks they will be ready to roll out. Some past great interviews include Jerry Schatzberg, Barbara Daly and Susan Wood.

I’ve been working on several pieces for the newsletter that are taking a bit longer than planned, so today I am sending you an article on Rifat Ozbek’s cultural inspirations I wrote a few years ago for Heroine—the sister site for Grailed, it was shut down in 2021. I love Ozbek’s work and collect it, but I often feel like he doesn’t get the attention he deserves—here is just a small segment of his oeuvre, which will hopefully make you want to delve a little deeper.

The high fashion designs of Rifat Ozbek in the 1980s and 1990s reflected his interests in both world cultures and street culture—he blended multicultural influences and street style in a novel and groundbreaking manner. While primarily remembered for his ethnically inspired clothes that reflected his Turkish heritage, Ozbek’s decades of work actually featured a far greater breadth of source material and included a multitude of diverse aesthetics and silhouettes. Incredibly influential during his twenty years in fashion (1985 to 2005), his garments and styling continue to define styles today—many of the retro 1990s trends of the last few years are directly lifted from his supermodel-laden runways, including crushed velvet leggings, pajama tops, bomber jackets, bra tops, and biker shorts. The blending of many different cultural motifs and silhouettes into one runway show, which is often seen today, can also be charted to his work.

Ozbek first came to England at 18 to study architecture in Liverpool; unfulfilled by the heavy emphasis on math he soon returned to Istanbul. Once there he met a local fashion designer and through him realized fashion was his true passion; he was accepted to study fashion at the prestigious Central St. Martin’s in London on the basis of eight sketches. After graduating with honors in 1977 he worked for Walter Albini in Milan and Monsoon in London before establishing his own line in 1984. As an unknown designer Ozbek was denied entry to show his first collection at Olympia, where most London fashion week shows were held at the time. Instead, he introduced his first collection (with backing from Gulf Oil) in his parents’ apartment in Knightsbridge—the unlikely location did not dissuade the press and buyers, who were immediately captivated by his close-fitting (an ode both to his architectural training and his favorite designer, Alaïa) designs with ethnic overtones (crescent moons, stars and bead featuring heavily in the next few seasons).

At the time he remarked that to wear his clothes, “You have to be confident and a bit strong.”1 For day, his simple suits and dresses were cinched but not tight, both figure-conscious yet fluid—a blend of sexy, sensual and work-appropriate that made him the darling of working women and superstars. He quickly became a favorite of Princess Diana, Cher, Madonna (for whom he made a custom jacket with the Virgin Mary emblazoned on it), Diana Ross and Michelle Pfeiffer. In 1987 he launched a secondary line, O for Ozbek (later changed to Future Ozbek), with the help of Italian manufacturing partners. Just four years after his debut, Rifat Ozbek won the British Fashion Council’s Designer of the Year Award in 1988, where he was celebrated for his unique style and vision.

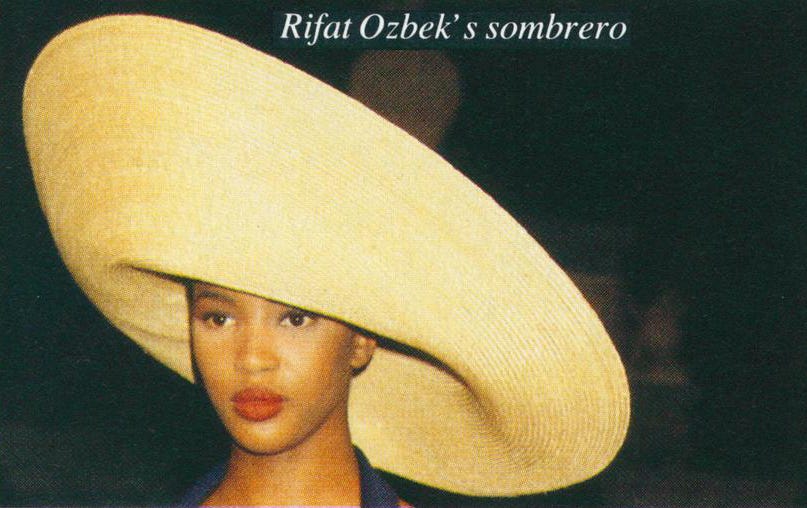

Deeply enmeshed in the world around him, Ozbek traveled often to gather inspiration and mixed “ethnicities with assurance and precision.”2 While his first collection cleverly used Fortuny fabrics in a tribal African theme, for the spring/summer 1988 collection he recalled a trip to Mexico—complete with serape-striped knits, tight-fitting mariachi biker shorts and micro-minis adorned with silver chain buttons, and peasant shirts with cotton bolero jackets that were shown with gigantic straw hats (loosely based on the sombrero and made by Phillip Sommerville) that later inspired Jacquemus’ swooping hats for spring/summer 2018. Never heavy-handed in his cultural appropriation, Harper’s Bazaar remarked that he made ethnic fashion chic again after years of “baggy, hippy-dippy clothes.”3 This was done through simple, sensuous cuts and by bringing in his contemporary world of London nightclubs and parties.

Ozbek cultivated and reinforced the clubland connection in his clothes and collections—the soundtrack to the fall/winter 1989 runway show included House music mixed with muezzin chanting, the S/S 1990 show featured a disco ball, while his alternately loose, flowy or tight, stretchy garments were perfect for dancing all night in. The fluorescent shades of Acid House mingled with dark velvets and leopard print, while bra tops and sarongs jangled with chains and ball buttons—a complex interweaving of different cultures that made Ozbek’s clothes highly covetable.

At the turn of the decade, Ozbek shifted his emphasis to spirituality and created several “New Age” collections that are eerily in keeping with wellness trends of today. For his spring/summer 1990 collection, “printed in white on clear acetate was a word list: love, Zen, Tao, karma…invoked every new-age catch phrase he could think of to conjure the generous spirit of the 1960’s. His models wore unisex overalls, body shirts and jackets emblazoned with the word ‘Nirvana.’ They toted silvery backpacks, flashed crystal pendants—and beatific smiles.”4 Rifat described this all-white collection as “hip-hop Zen,”5 and showcased pairs of Nike running shoes bedazzled with rhinestones. The rediscovery and reinterpretation of hippie spirituality in the “second Summer of Love” (1988 and 1989) was closely linked to the rise of acid house music and the euphoric states provided by illegal drugs like ecstasy.

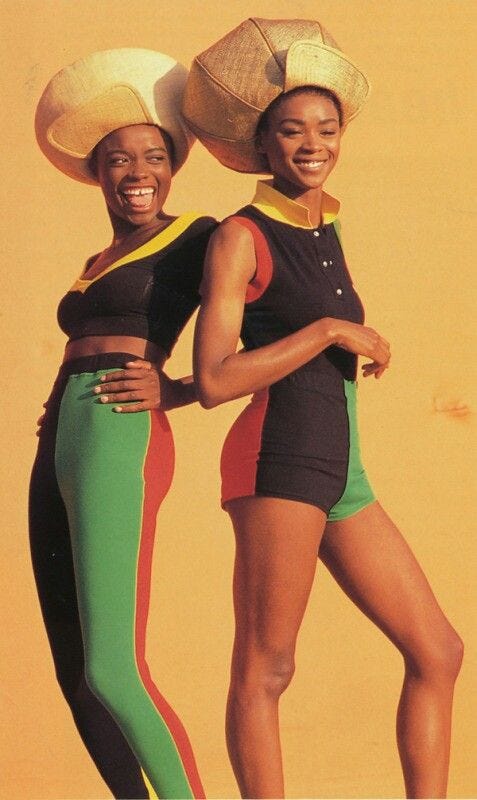

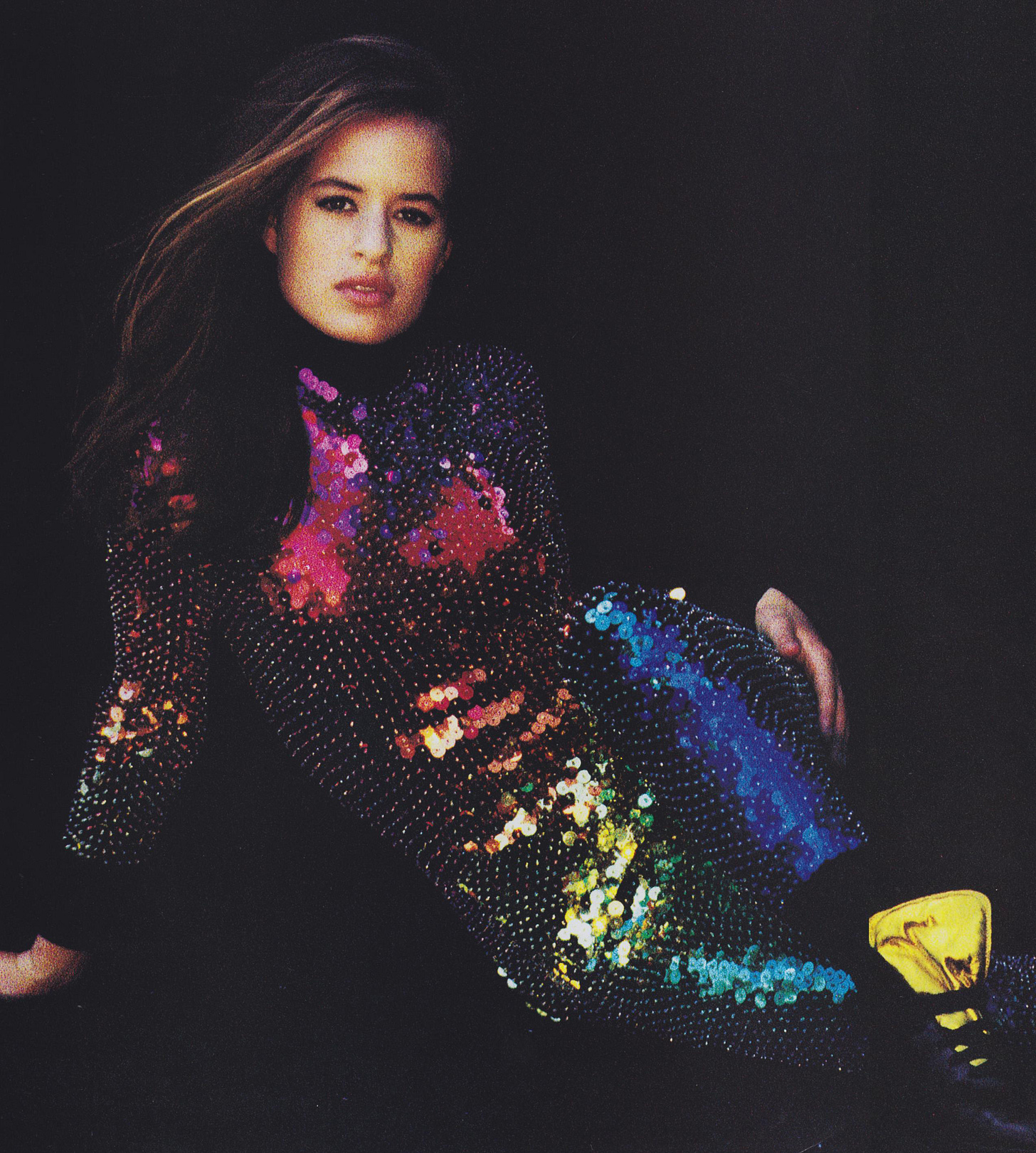

Choosing to forgo a runway show the following season, he returned to color by presenting a psychedelic fashion video. Dancing across the screen to hypnagogic patterns, his rainbow sequin jumpsuits and dresses were precursors to similar designs shown decades later by Pucci and Ashish. Always keen to bridge the gap between the “ethnic/primitive” and modern technology, for spring/summer 1991 he produced African tribal patterns using computer printers and embroidered CDs onto bomber jackets. His Future Ozbek collection for that season was a riotous celebration of Reggae culture with color-blocked Lycra red/gold/green clothes and giant Rastafari hats made by Philip Treacy.

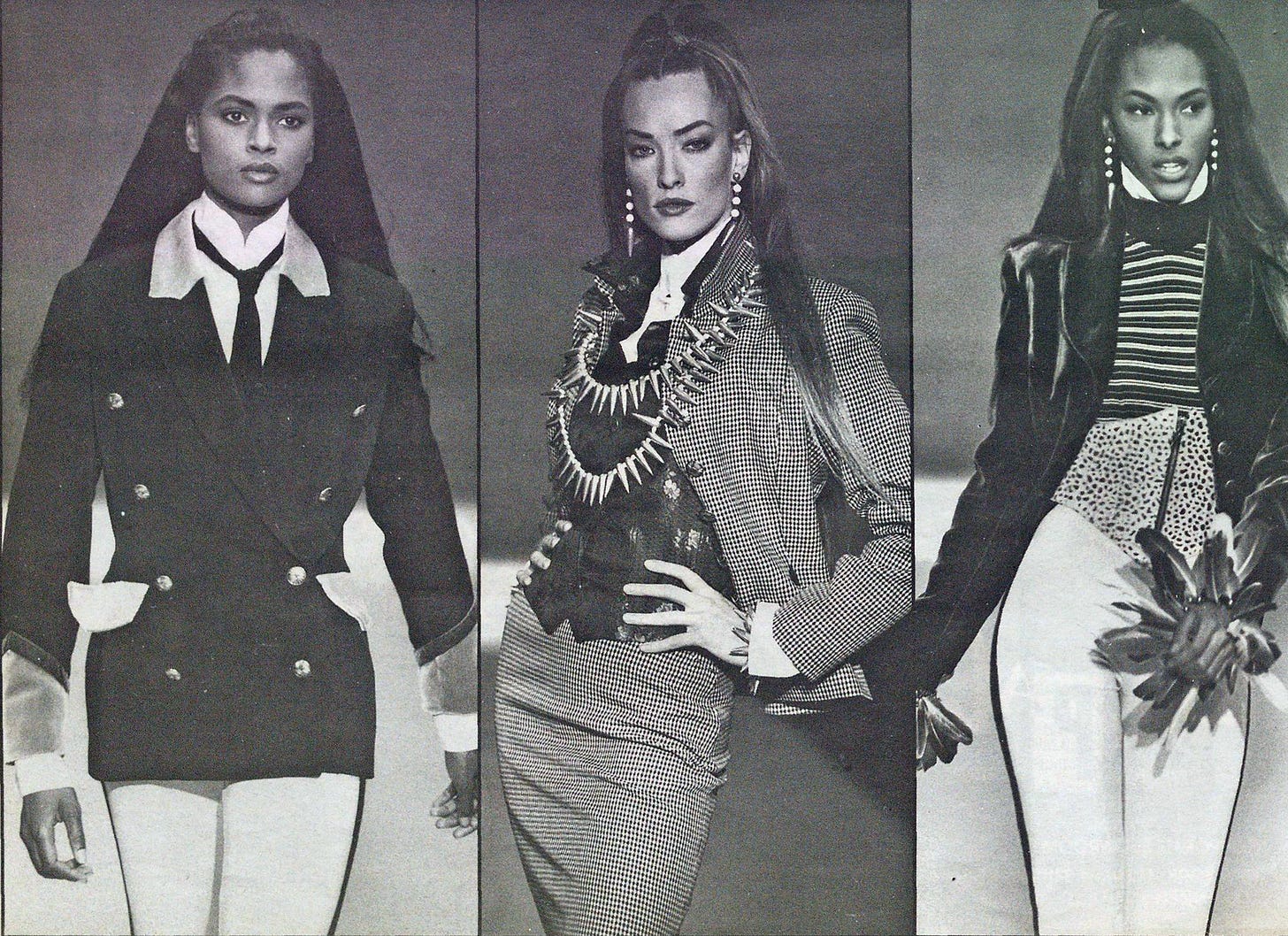

His decision to show in Milan provided him a larger, more globally recognized stage while also bringing some much-needed energy to a dull fashion week. Of his spring/summer 1992 collection, the New York Times wrote: “By midweek, a new-age English Turk named Rifat Ozbek had shot a flaming arrow into the tents of master tailoring, with an American Indian-inspired collection that made the conservative Milanese houses seem bland.”6 Not just referencing Native Americans, Ozbek also layered in other aspects of American culture such as cowboys and Confederate military uniforms. The elaborately trimmed cropped jackets and vests in Louis Vuitton’s fall/winter 2018 collection were definitely reminiscent of Ozbek’s early 90s collections, which were a media and sales success—and also led to him winning his second British Fashion Council’s Designer of the Year Award in 1992.

Later in the 1990s, Ozbek showed in Paris and New York. With the shifting political climate and the rise of political correctness came an increasing understanding of cultural appropriation by the press—at times Ozbek’s brand of ethnic celebration was called out for taking the “cultural cartoon route” (for example with Romani Gypsies for fall/winter 1997.)7 He fared better when sticking more closely to his own background—mining the tropes and history of the Ottoman Empire. Rifat Ozbek closed his house in 2005 to concentrate on designing interiors; he also designed a clothing collection for Italian footwear brand Pollini from 2004 to 2008. In 2010 he launched YASTIK, an exclusive range of cushions made from hand-woven Ikats and Suzeni embroideries sourced from remote areas of Central Asia and Uzbekistan. With wholesale accounts worldwide, YASTIK has provided Ozbek with a new route for sharing his passion for world cultures and textiles. While now better known among high society for designing the interiors of some of the most acclaimed clubs and restaurants in London, Rifat Ozbek’s fashion designs are still highly collectible and making an impact on both the runway fashions and streetstyle of today.

“Body-Sculpting Trendsetter Ozbek,” Harper's Bazaar, April 1988.

Eve MacSweeney, “Hugging the Curves,” Harper's Bazaar, September 1989.

Ibid.

Ruth La Ferla, “Marketing the Millennium,” New York Times, January 14, 1990.

Woody Hochswender, “In London, Subway Style Above Ground,” New York Times, October 19, 1989.

Woody Hochswender, “Milan,” New York Times, December 15, 1991.

Amy Spindler, “Treating History With a Sense of Pride,” New York Times, March 17, 1997.