Last week I introduced you to fashion designer Richard Assatly and brought you up to his first solo collection, in February 1976. Today I cover the rest of his career and life, ending with his death from AIDS-related complications in 1993. Here is a look into his home.

“I hope to make easy, wearable clothes for today’s life style.”

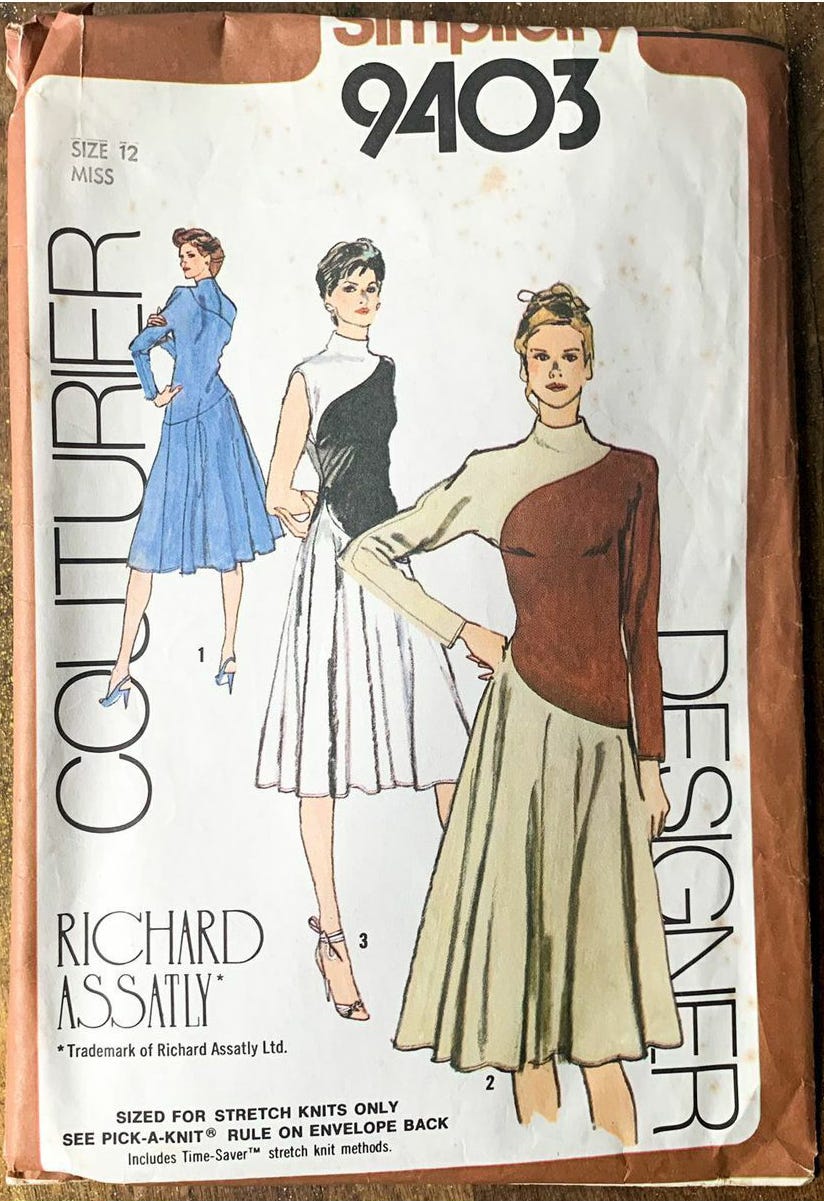

For Richard, getting his own company was an important step: “Becoming a partner is making a businessman out of me. I see that designing is more than just creating; it’s editing and merchandising a line well. Because if you don’t have a firm financial foundation, you don’t have any real artistic freedom.” How that freedom manifested for him was in creating easy-to-wear designs that truly took into consideration how a woman lives: “Women’s more independent, active role in life today has as much to do with my approach to clothes as fabric, color, comfort and practicality do. When I design an evening dress, I try and remember a woman isn’t going to have a limousine or coach picking her up. She’s probably going to run out and hail her own cab. Little tiny buttons down the back of a dress may look wonderful, but who on earth is going to get her into it if, like many women, she lives alone?” That sense of comfort and practicality extended beyond day and evening clothes; following in his father’s footsteps, Assatly also began designing a line for the loungewear company Loungees in 1977.

Though Assatly’s price point was lower, the press situated him alongside the greats of New York fashion: Halston, Beene, de la Renta. Within a year of his first collection, the legendary Dawn Mello (then in the process of reviving Bergdorf Goodman, later to hire Tom Ford at Gucci) was telling WWD, “I think Richard Assatly has matured to the point that he is one of our most important designers.” The softness of late seventies fashion suited Richard; though he’d started in tailoring, flou was where his talent for highly imaginative combinations of textures (“inky-purple silk tussah skirts and skinny pants paired with white jacquard gauze blouses and plaid silk noile shawls”) and colours (“turquoise linen with manila chenille or natural wool leno with bright berry”) emerged.

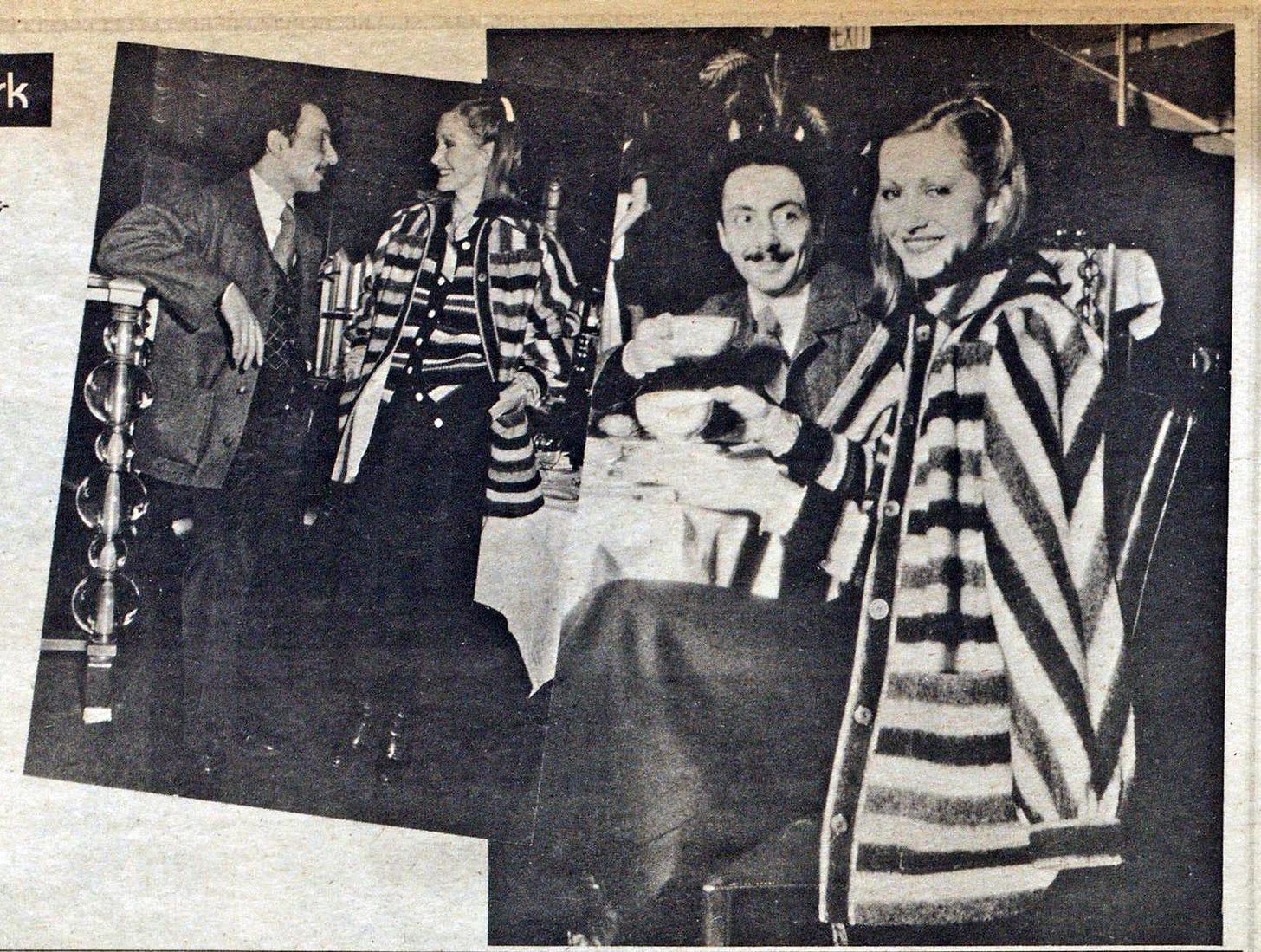

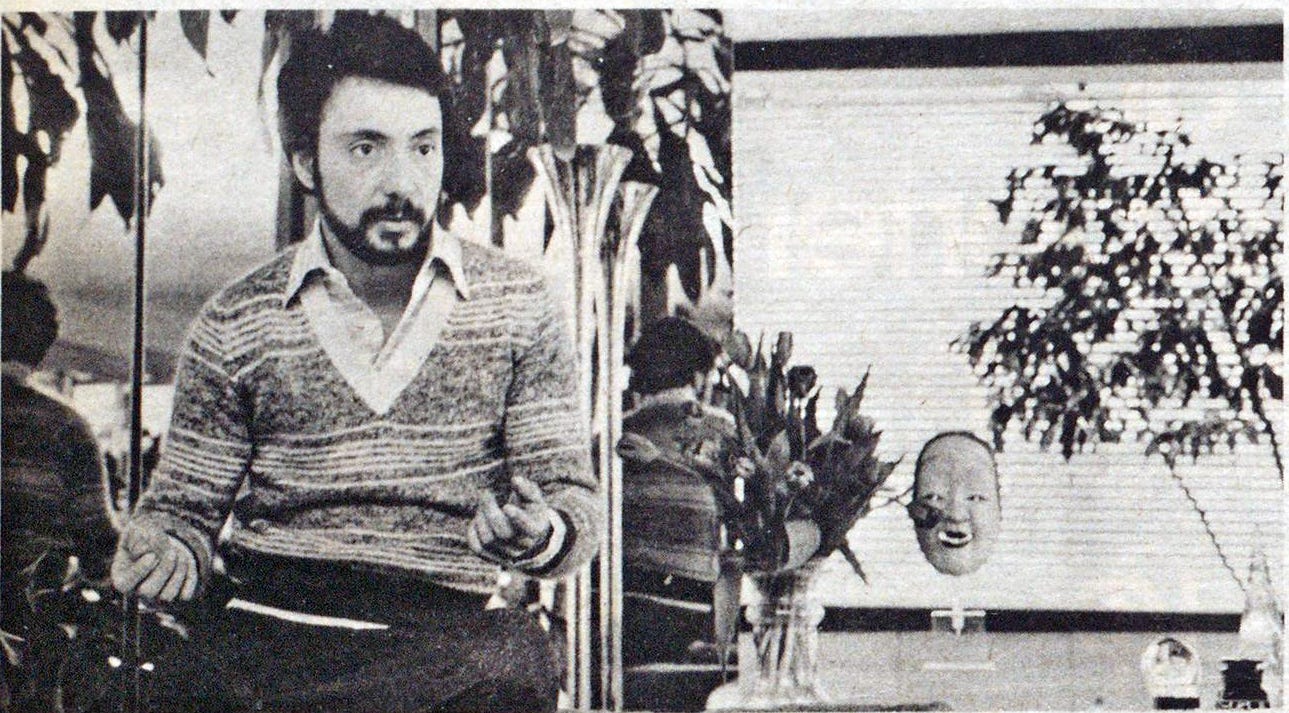

Unlike many of Assatly’s contemporaries and fellow graduates of FIT—such as Stephen Burrows—Richard’s social life was not part of his design process and media presence. His private life was completely separate from his work, and it did not inform his designs (at least not in an obvious sense). Assatly was friends with designers like Dell’Olio, Karan, Patti Cappalli and Maurice Antaya—they enthusiastically attended each other’s shows, but their social interactions weren’t recorded in gossip columns nor used to create a mystique around their work. Because of this, little was written about Assatly’s life in newspaper and trade journal articles; at most, he was called “shy.” One piece from 1976 describes Richard’s apartment as having a “modern, mirrored living room… enriched with impressionistic paintings, butterscotch Corbusier chairs, art deco and Egyptian pieces and two glassed-in, greenhouse-like extensions.” Assatly himself cut an elegant figure—wearing gabardine suits all summer, tuxes for fashion events, a lush moustache, and often a pair of aviator shades.

Richard’s earlier tailoring designs for Ginala had often reflected a subtle forties influence, and when he began to incorporate more suiting into his collections again in 1978 that 40s-element reappeared—presaging the 1980s with broad-shouldered boxy hip-length jackets, whether wrapped-and-tied or double-breasted, paired with a narrow skirt or lean pants. He called it the “T-formula”: “The letter T stands for timelessness, taste, today and tomorrow. The T-formula is what current fashion is about.” The leaner look with defined shoulders—whether a black evening dress, a blouson dolman-sleeve top over skinny trousers, or a skirt suit—appears to have been more Assatly’s personal taste than the peasanty flou of 1976-77; those years appear more of anomaly against the litheness of prior and later years. No longer needing to distill down fantasy trends to make them work for him, Richard could simply make what he excelled at. In the words of a Saks Fifth Avenue ad: “Pared down. Honed down. You’ve seen it coming for a long time, now. The word. The shape. The feeling—narrow! Not just an absence-of-layers-narrow. But a newer, softer, all-over leanness. Litheness. That makes you feel somehow taller, slimmer. Leggier. Sexier. Yes, it’s different. It’s strict—in the sense of being not one bit frilly or overdesigned. And it’s definitely not for the timid. What Richard Assatly has done is just clean, bare, stark black form… pure and gloriously simple!”

In early 1978, Joseph Snow left Gino-Snow; within months, the firm was renamed Richard Assatly, Ltd. The business was said to be “doing a big volume with career women who will spend $150 for a fine dress.” For the most part, Assatly seemed to be courting a slightly more mature market; in 1979 he told the Boston Globe, “There’s a new interest in looking dignified. Women are no longer afraid to demonstrate their intelligence. Instead of looking what the fashion world calls chic, they want to look smart in the real sense of the word.” Neat, ladylike, accessorized with perfect little hats (made for Assatly by his assistant Kirsten Randolph) and gloves—yet the execution was more future-thinking than retro through Richard’s highly individual use of colour. For spring 1980, Richard introduced Assatly Additions, a new lower-priced blouse line that was extended into a full sportswear division later that year.

Reviews of his shows in the early 1980s were more mixed than they had been previously; the day clothes were still universally lauded, with his evening designs often described as overwrought and overdesigned. By June 1981, the company started liquidating, stating that business had been very difficult at retail—they shipped early fall but stopped all production after that. At its peak, just 3 years earlier, the firm had done $4.5-5million a year. While it is not exactly clear why there was such a sudden drop in sales, it might be due to changes behind the scenes. Joe Snow had managed production; after he left and the company was renamed, there might have been decisions made regarding fabrics and production quality that lessened the product’s desirability.

Assatly’s designs have a freshness and a liveliness in period photos that hasn’t been retained in those available on eBay and other resale sites. Most of the pieces I have seen for sale have the later “Richard Assatly Ltd.” label. As that line had been positioned as an affordable contemporary one, lower quality fabrics were seemingly used—something that is particularly apparent in the man-made fibres. His cottons—which I find the most charming in old photos—rarely come up for sale, but seem to have maintained their “practical chic” much better than the viscose and polyesters. While the choice of fabrics and price point was obviously a considered choice and one that was highly profitable for Richard and his partners, it, unfortunately, has contributed to Assatly’s forgotten legacy—what remains honestly just doesn’t look that good. While I do not know for sure if Richard Assatly for Gino-Snow used significantly better fabrics, it appears likely from what is available on the resale market and from photos.

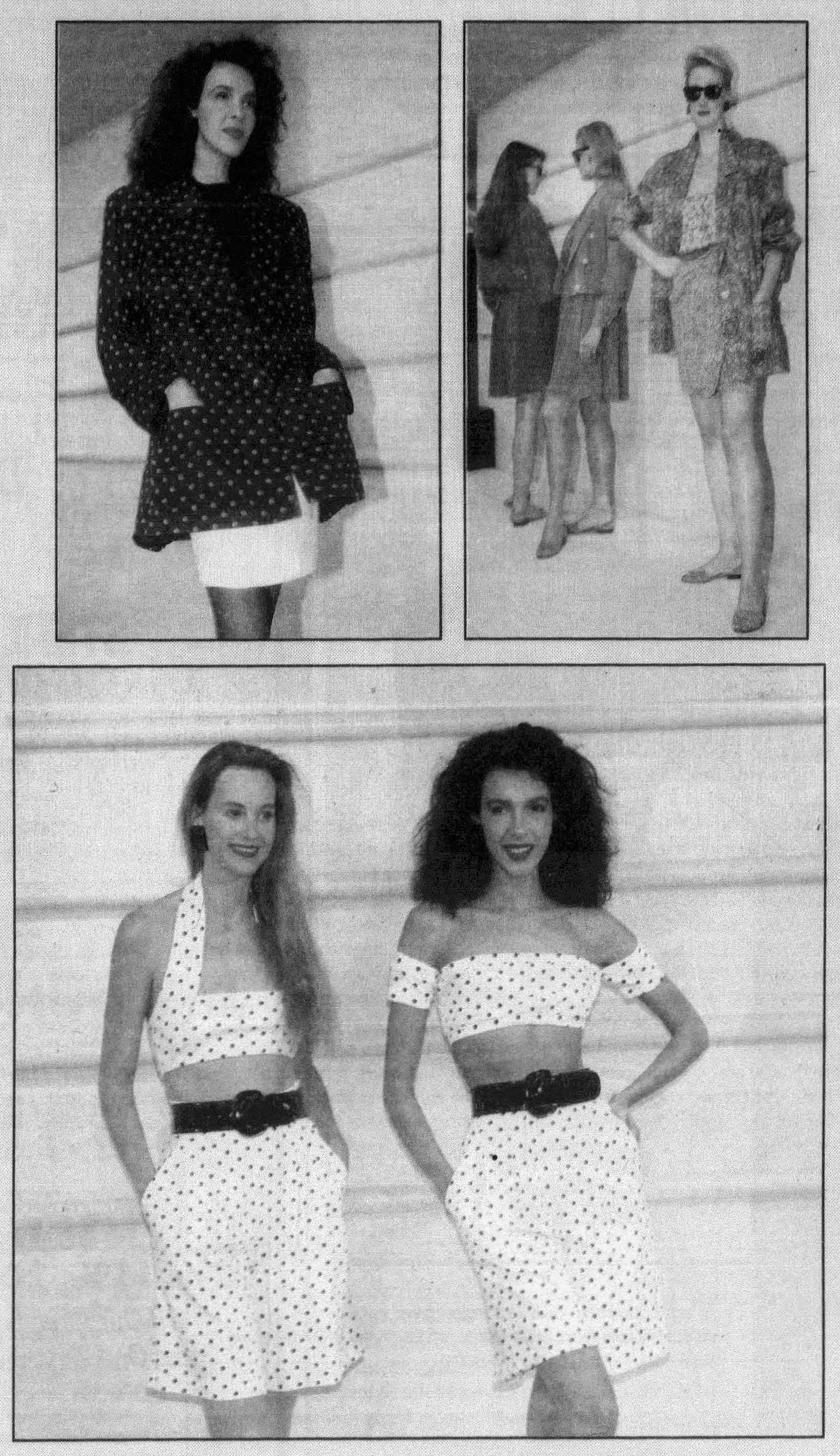

After the closure of his company, Assatly freelanced for other companies around New York. In February 1983 he was announced as designer at Benton, Ltd., a firm focused on late-day-into-evening suits and dresses. A year later it was reported that Assatly was to design the “Dynasty” ready-to-wear collection. Nolan Miller’s glamorous costumes for the TV show had been a major driver of fashion trends and audience viewership, but his designs had been less easily translated to retail. Assatly was a Dynasty fan and someone clearly skilled at the kind of sharp-shouldered suits beloved by Alexis and Crystal, so was a smart choice for the line’s designer. Years ago I did extensive research into Dynasty, its clothing line and licenses (including interviewing Miller before his death); as I’ve found only limited mention of Assatly, I believe that at most it was a one-off contract gig.

By 1986, Assatly was designing Anne Klein II alongside Maurice Antaya—under his old friend and Anne Klein head designer Louis Dell’Olio (Donna Karan having left in 1984 to start her eponymous line). A lower-priced complement to the main Anne Klein collection, Anne Klein II focused on versatile work and weekend clothes. Assatly continued designing the line alongside Antaya until his death from AIDS-related complications on July 25th, 1993; he was supposedly still sketching up until his last days. Longtime friend Donna Karan was quoted in his New York Times obituary: “His clothes had a real modern edge. He followed the general direction of fashion, but he gave his interpretation a special twist. Basically, he was a tailor—he made beautiful suits—and he was able to translate this tailoring skill into dresses that were severe but sexy.” Dell’Olio, who Assatly worked with at Originala and Klein, said that Richard’s clothes were “young and always of the moment—he seemed to feel what was going on before it happened.” Assatly was just 49 at the time of his death.

What is clearly missing from this is a sense of Richard as a person beyond being a designer. If you knew Richard, please get in touch as I would love to interview anyone who was friends or worked with him. So much talent was lost to AIDS, so many memories—I would like to do what I can to save some of those recollections, particularly about lesser-known designers and creatives.

I just found and bought a suit of his on EBay - it is gorgeous and was ludicrously cheap!