Uncovering Richard Assatly: Part I

In February, I wrote up a short biography of Bobby Breslau, an American accessories designer lost to AIDS in 1987. At the time I wrote, “Losing, as we did, a whole generation of men to AIDS has left so many stories untold and unremembered.” Here is another one of those stories—another designer who seemingly has been forgotten and omitted from fashion history. As so little is available elsewhere on Richard Assatly, this essay is long and divided into two parts—the second part will be sent out this time next week, followed by a newsletter on his home.

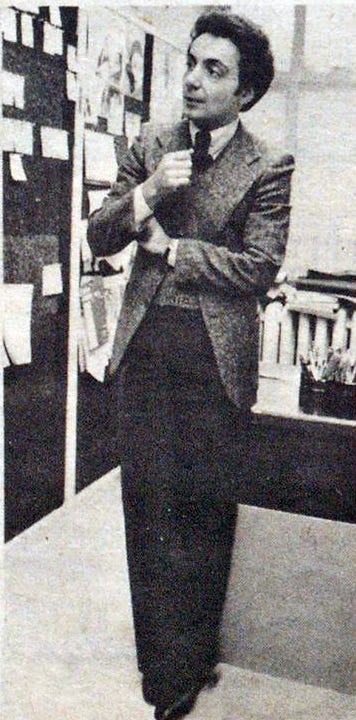

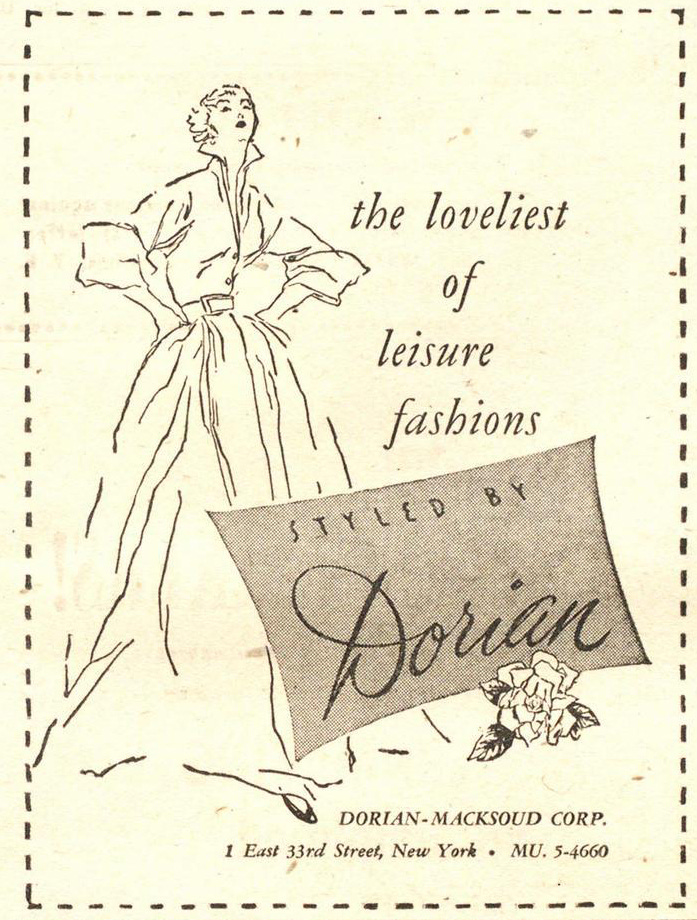

Born in Brooklyn in 1944, Richard Assatly was raised in the fashion industry—his Lebanese immigrant father and uncle owned the loungewear firm Dorian-Macksoud. From the age of seven, Richard was drafting up designs that he proffered to his father, who was less than happy about his son’s passion. Years later Richard said, “He always told me that the fashion business was dirty, cut-throat and to stay out of it. He wanted me to be an accountant.” To please his father, he matriculated at Rider College in Trenton, N.J., to study business while also working part-time at a bank; “I couldn’t balance the sheets. Even my personal checking account was in a disastrous state. And when I was supposed to be taking telephone messages, I doodled fashion ideas on the note paper.” After his father passed away suddenly, Richard took it as a sign to align with his true purpose; he used his savings account to enroll at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, where he particularly excelled in tailoring. While studying he worked part-time in Dorian’s shipping room and did freelance display jobs for Lord & Taylor and I. Miller.

Richard graduated in 1967 and swiftly found work as an assistant designer for Pat Sandler at Highlight; “That’s where I learned to put a collection together.” In 1968 he was hired by the Seventh Avenue coat and suit firm Originala to be the designer for their junior division Ginala, though without label credit. Ginala was launched in May 1966 as a collection of coats and suits for junior and petite sizes. Already his designs were marked by a sleek spareness that they would retain throughout his career, no matter the larger trends. According to a 1970 Atlanta Constitution article, Richard’s philosophy of fashion was reflected in two points he always strove to consider in his designs: “…the number one requisite of a fashion collection is that it offers clothes that can be worn anywhere; number two—that today’s woman who he seeks to dress wants jet age clothes rather than look like something out of the past.”

1970 was the year of longer lengths and the highly controversial midi. While Paris and Women’s Wear Daily pushed the longuette, Seventh Avenue scrambled to quickly produce the new trend and find a way to market it to the mini-loving American public. Suddenly tasked with incorporating the midi into his collection, Richard made what he later called his “first big, bad mistake.” He dropped the hemline of every piece in the collection without changing other elements of the design: “Adding length to a garment designed to be short is an eyesore. There was so much confusion in the fashion market that no one objected—except the customer who didn’t buy those first awful midis.”

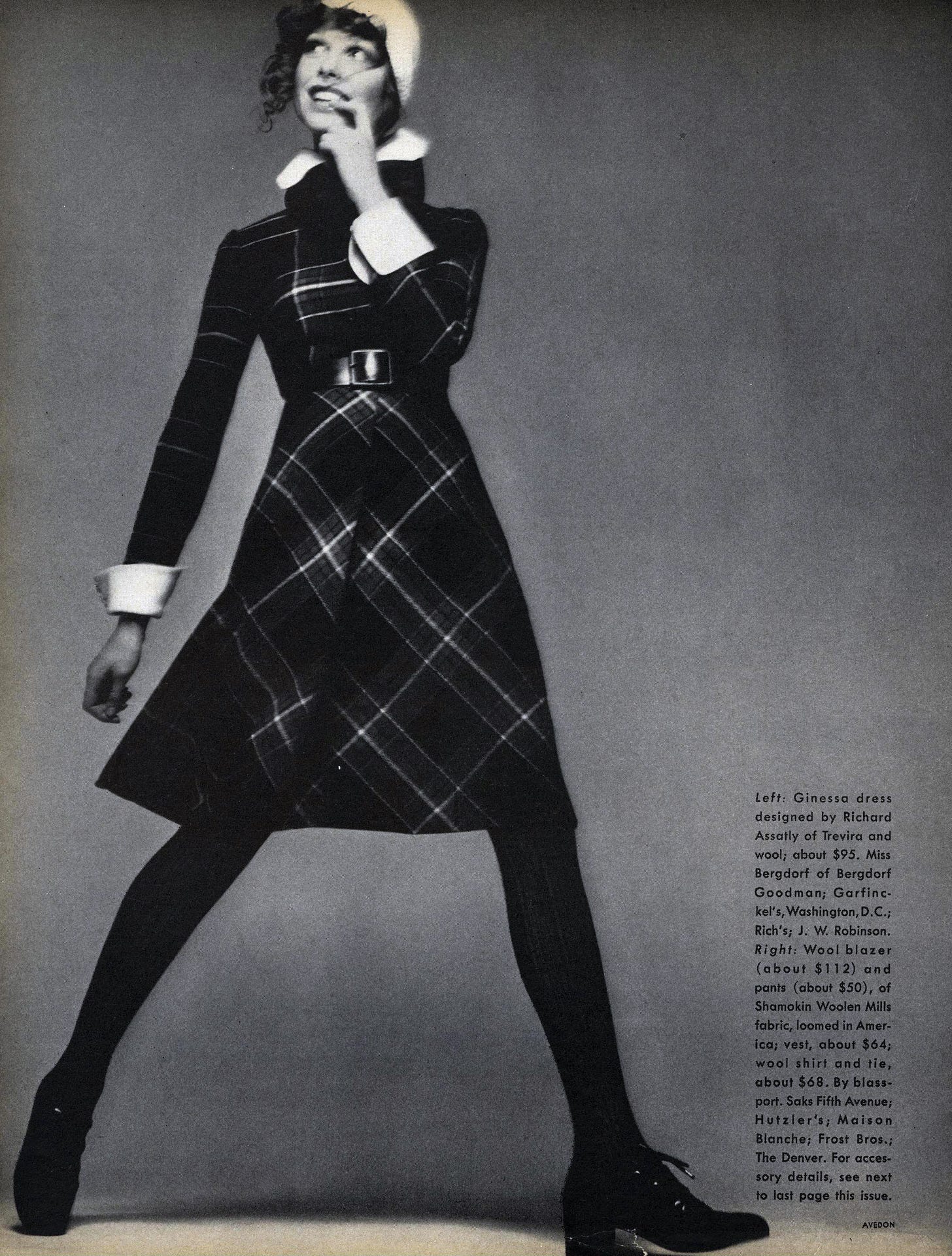

At Ginala, Assatly excelled at designing softly tailored suits, coats and separates that could be worn interchangeably; as he told one interviewer, “Listen, my mother is the utilitarian type who taught me that you don’t need a lot in life to survive. Actually, that’s a great fashion principle. A few well-chosen clothes go a long way.” For day, a gray flannel pea coat and watching skirt; for evening, a black-and-white Prince of Wales check taffeta blazer and matching pleated skirt; maybe throwing a wool midi-coat with detachable capelet over top. Ginala was doing well enough that in 1971 Richard was given another new division, Ginessa, for “popular-priced… coats, suits and dresses.” Additionally, Richard was also head designer for their rainwear line, Aquanala, and sometimes also designed for Originala’s expensive main line, alongside Louis Dell’Olio (who left in 1974 to become co-designer at Anne Klein with Donna Karan).

When Originala launched a lower-priced rainwear line, Aquatogs, in 1975, Assatly was now in charge of four divisions. For Assatly, the four lines (Ginala, Ginessa, Aquanala, and Aquatogs) “are all one concept and feeling... They’re all softly tailored things that are classic but contemporary. I don’t feel, for example, that when I get a shape for a dress that it can’t be carried through into a jacket or a raincoat.” Only 30, Assatly felt that he had “literally grown up” there—“I started designing for Originala when I was 23… Over the years, I’ve taken on more and more design responsibility and I like it—it’s helped me develop.” These were not glamorous lines to be designing, but Richard was known for doing a particularly good job within the limits of these divisions. As one Joseph Magnin buyer was quoted in WWD, “He always brings a fresh, clean, innovative look and well-made clothes to a place in the market that might be boring otherwise. It’s difficult to find one designer that sells in all our stores—Denver, Hawaii, Nevada and San Francisco—and he does. We’ve had nothing but success since we started with him.”

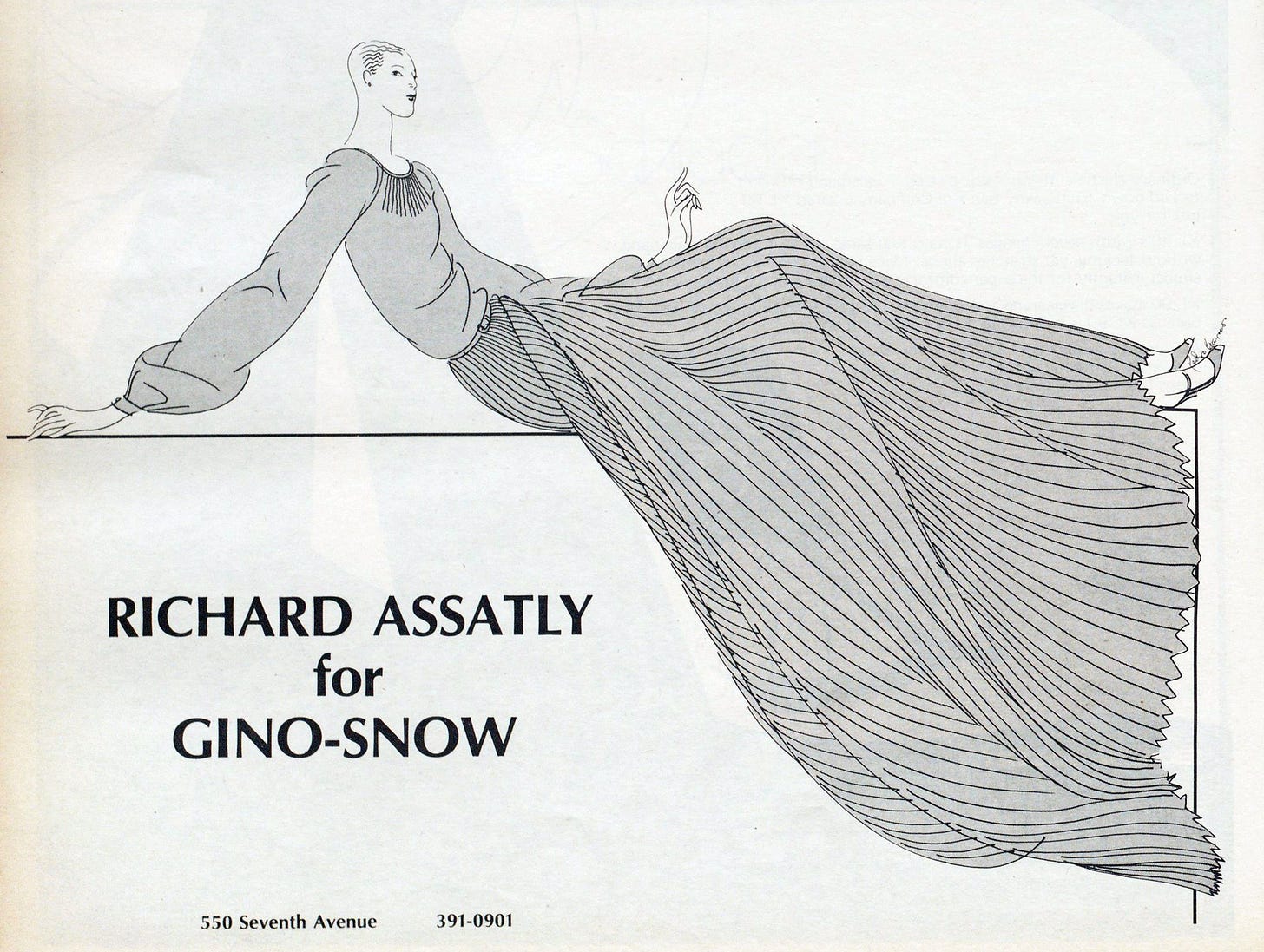

Assatly stayed in that position until late 1975, when a button salesman told him that a “man around the corner” was opening a new fashion business and looking for a great designer; Assatly remarked later, “That’s the way things are done in the crazy world of fashion. Someone who knows someone who knows someone.” He met with Gino de Georgio (formerly sales manager for Peter Clements and Chester Weinberg) and Joe Snow (previously VP and sales manager of Giorgio di Sant’ Angelo, Geoffrey Beene and Donald Brooks) for lunch, where they offered him the job of designer at their new firm Gino-Snow—complete with his name on the label and a percentage of profits. With backing from entrepreneur Ben Shaw, Richard Assatly for Gino-Snow was incorporated on November 1st. “Fashion is a nervous business. One day you’re in and one day you’re out. A piece of the rock seemed like enormous security.”

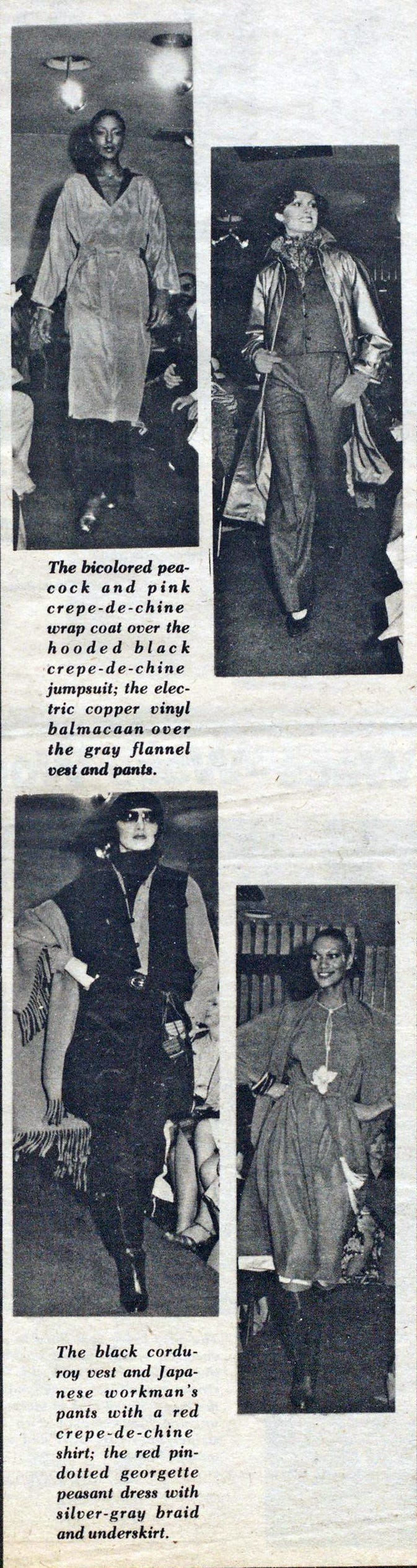

The first Richard Assatly for Gino-Snow collection premiered at the beginning of 1976, to a standing ovation from the press and buyers. With his own line, Assatly turned away from the “softly tailored” suits he was known for towards the simply soft—for spring/summer 1976 terrycloth playclothes, strapless chiffons and crepe jumpsuits mingled with loose tunics shown over pants. “I was plain nervous,” Assatly recalled, “just plain nervous. I wandered—and worried—about the transition to softer fashions from tailored coats and suits, the switch to cotton dresses and crepe pants, for example. Would anybody out there like it?” With headlines like “New star rises over Seventh Avenue,” Assatly and his partners needn’t have worried—within eight months, the firm had already done $2 million in sales on just two collections. With all items selling for between $100 and $200, they were described as “sleek clothes that have a Paris twist at United States prices” and were either positioned in the low-end couture or contemporary dress departments.

“Every so often, the American fashion world produces a designer who turns out to be one of those overnight sensations. Usually the designer name is neither easily pronounceable nor instantly memorable. But the heretofore ‘unknown’ behind the collection is a star because the clothes have distinct qualities that make cash registers jingle. That, in essence, is the story of a shy, 32-year-old bearded designer, Richard Assatly…”

- Marian Christy in the Boston Globe

Describing himself as a master at “practical chic,” Richard could be seen to be distilling the trends of the moment down into their essence—that fall, simplifying the peasant trend from a boisterously ethnic proposition to a sharply condensed silhouette. This was shown most keenly on a copper silk dress—loose blouson top and dirndl skirt—overlaid with a blue silk skirt, creating the sense of an aproned peasant ensemble but without the fantasy volume proposed by designers like Yves Saint Laurent. Alongside such looks, he showed a large gamut of styles—hooded coats, three-piece suits, a pleated poncho over a strapless evening dress—all “refreshingly uncluttered” and pared down; “The great thing about fashion today is that women can choose from a broad spectrum. Pants aren’t out. Skirts aren’t out. Nothing is really out—except bad taste.”

More to come next week…