The Cellini of Leather

Bobby Breslau's Wonderful World of Accessories

If you google “Bobby Breslau” all that comes ups are a post from The AIDS Memorial on Facebook and several home sewing blogs that have rediscovered his early 80s Vogue Patterns. How is it that a wonderful accessories designer, creative, and close collaborator of Halston, Stephen Burrows and Keith Haring has been so completely forgotten?

Losing, as we did, a whole generation of men to AIDS has left so many stories untold and unremembered. Thankfully we have The AIDS Memorial (on Facebook and Instagram), but these remembrance posts can only tell a tiny part of each story. For Bobby, the memorial quotes a 1989 interview with Keith Haring where he discusses Bobby’s death—but what of his life? Hopefully, this newsletter will be the first step towards making him more known again in the fashion world.

So far I have been unable to uncover any information about Bobby’s life before the late 1960s. According to his gravestone, he was 44 when he passed away in 1987—meaning that he was born in 1943, though I could not find any form of birth certificate online. By the late sixties, Breslau was at the center of a group of young, hip creatives in New York and Fire Island. Amongst his friends was fashion designer (and later, Hollywood director) Joel Schumacher, who later revealed: “There was a whole talented group that came out of Fire Island in the late ‘60s—Berry Berenson, Bobby Breslau, Tony di Pace, Elsa Peretti, Marina Schiano, Halston, Angelo Donghia—but I think all of them were very lonely. We all had difficult childhoods and we needed recognition. Not only did we need it from each other but from the status magazines as well. We fed each other’s creative juices and neuroses at the same time. We all wanted to be famous.”

Among Breslau’s close friends was the emerging designer Stephen Burrows, then starting his career designing for O Boutique. In around 1969 Breslau left a job as a graphics designer to work with Stephen there. The following year the pair moved into a seven-room apartment in the East Village. According to a 1972 interview with Burrows, they had completely redecorated the flat for pennies, “transforming [it] into a shangri-la with plants crowding every room.” Bobby’s bedroom was painted black, while Burrows painted his dressing room blood red. Burrows said of their home, “Our purpose is to create a world of interest in which we live. You have to create the world you want to live in. It’s all there to be used. How, when and why is up to the individual.” That same year Schumacher introduced Burrows to Geraldine Stutz, then president of Henri Bendel, who poached him for the department store. Stephen Burrows’ World, a boutique on the third floor of Bendel’s, opened summer 1970 with Breslau as manager.

Burrows would dress up Bobby and their group of friends in his fantastical color-blocked pieces, hitting the town and drawing attention wherever they went—clever marketing that helped Burrows garner Coty Awards and offers of licensing deals. At some point in the early 70s Breslau became Burrows’ assistant, before starting the transition to accessories designer. There are two origin stories for the creation of Breslau’s first bag—both told by him to the press, five years apart. According to the first, in 1973 he designed his first bag for one of Burrows’ runway shows: “The whole concept of the bag came from a Japanese puzzle bag Elsa brought back from Japan—one of those bags that just folds and ties and has no seams.” In this story, after Burrows signed a deal with a Seventh Avenue manufacturer, Breslau decided to “go out on my own.” All handmade by Breslau in his East Village apartment (no longer shared with Burrows), he gave the first of his bags to Elsa, who he called “my inspiration”; the second was given to Carol Channing, and then to all the ladies of his group of friends—Schiano, Berenson—as well to Joe Eula, an illustrator and close collaborator of Halston; this led to Breslau designing variations on his bag for Halston.

The second starts with Halston asking Bobby to make him a fringed toy and some fringed pillows. To research construction, Breslau bought a baseball: “Two pieces of leather stitched together to form a sphere with one continuous seam.” He made a pillow with leather cut to the same shapes, finished with fringing. After the lingerie designer Fernando Sanchez mistook it for a handbag, Breslau sewed a strap on and a totally new style of purse had been created.

Regardless of which story is true, the large squishy pouch of soft kidskin became Breslau’s signature. Expanding on the original oversized black leather slouch, Bobby “made some of his bags in numerous colors and sizes, and they were shown with a Halston collection. They gave a jaunty, young, carefree look to the spare Halston clothes and caught the eye of every fashion pro in the audience.” It was an instant hit—while only available by custom order from Halston’s boutique, it was quickly copied by manufacturers at all price points and Breslau was credited with revolutionizing the handbag industry through his soft, crushable pouches. According to one newspaper, the design was chosen by the Smithsonian “as part of a permanent collection of 20 of this century’s most influential looks in American fashion,” though I have yet to find evidence of this.

Breslau said of his experience, “Halston and Joe Eula were the teachers. Working with them was like going to the best university in this country. The best fabrics, best tailors, everything quality. Joe has taste par excellence. ‘Keep it clean,’ he’d always say of any designs. Elsa has always been the inspiration; Joe and Halston the encouragement and the staunch supporters.”

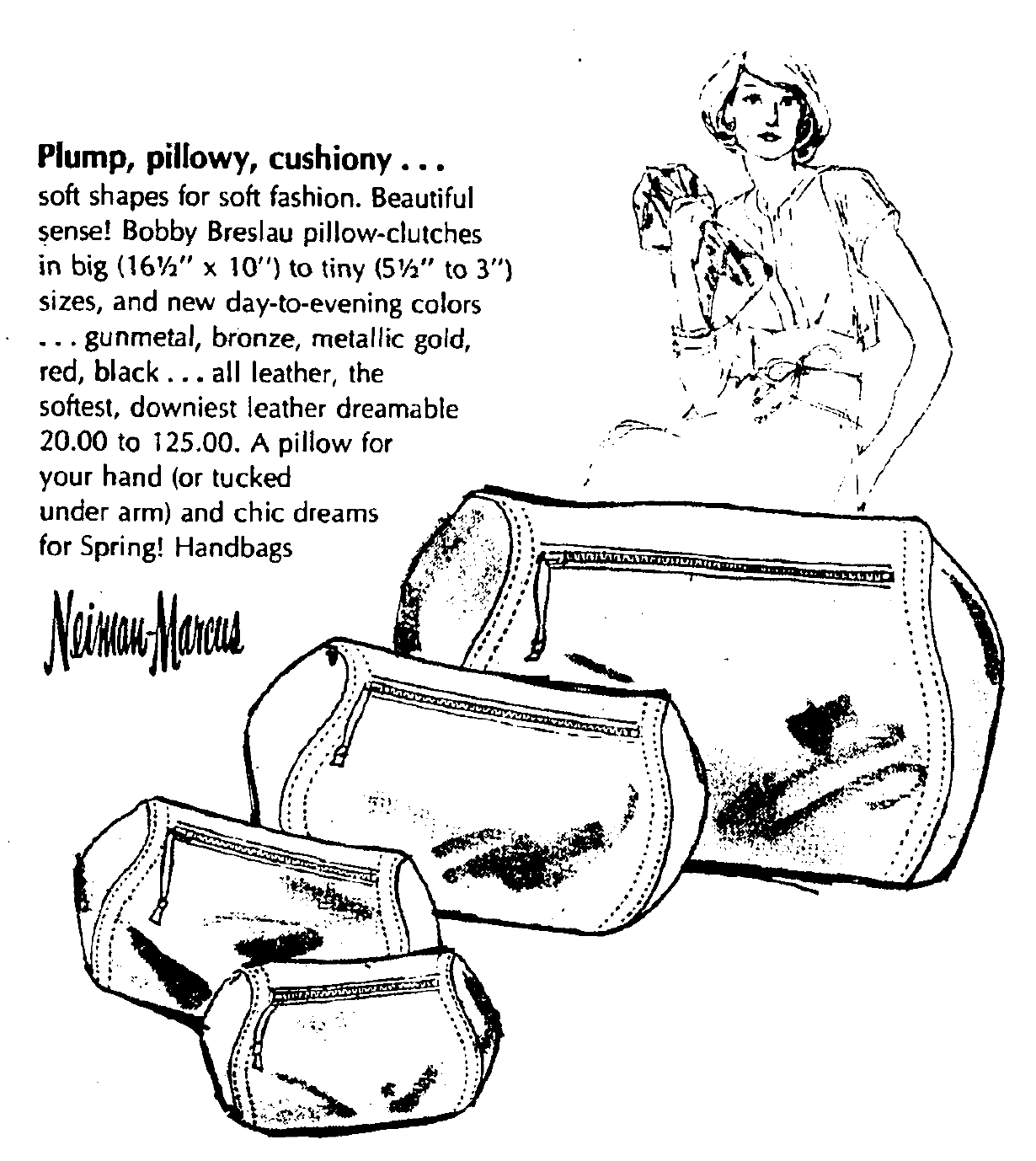

In 1976 Breslau signed a deal with Andrew Manufacturing Company, a subsidiary of Andrew Geller, Inc., known for producing high end shoes. Breslau got his own label and the manufacturing power to produce his designs at a much lower cost than this custom, handmade creations. His bags and belts were everywhere; prices ranged from $20 to $125. To balance his famous sack—“large enough to fit a weekend wardrobe”—Breslau came out with what he called “the littlest hobo of them all.” A tiny pouch on very long skinny straps, it could be worn over the shoulder, around the waist or tied in a bow at the wrist—though not much more than a roll of cash could fit in one. In 1977, when Burrows collaborated with Whiting and Davis—a company known since the 1890s for metal mesh bags—Breslau designed soft metal mesh pouches and clutches to pair with Burrows’ disco-friendly metal halters.

His Vogue Patterns—providing home sewers with the directions to make leather or fabric saddlebags, drawstring purses, tie-up shoulder bags and oblong roll pouches in three sizes—premiered in spring 1979. A version of his original slouch bag was also done as a pattern under Halston’s name for McCall’s in 1975.

It is unclear when this manufacturing deal ended; by the early 1980s Breslau was back to producing handmade leather goods, now producing leather hair ties, hairbands and scarfs in addition to a multitude of soft, unstructured bags. Breslau became Keith Haring’s production manager in the mid-1980s, putting to good use the skills he’d learned in the garment trade by helping Haring mass-produce goods with his characteristic line drawings on them. When Keith Haring opened his Pop Shop on Lafayette in 1986, Bobby returned to his retail roots and became manager.

Breslau passed away on January 30, 1987; he is buried in a Jewish cemetary in Connecticut. I found no obituaries or mention of his death in the press—after a certain point, he just ceases to exist in the media except for the aforementioned, posthumous mention by Haring. Breslau, like many other men with AIDS during that period, simply faded out. As Haring told Rolling Stone, “I think he knew that he was really sick, but it wasn't diagnosed as AIDS for a long time. By the time he went to the hospital, he died within a week. And that ... that was almost… that was like pulling the rug out from under me.” On March 20, 1987, Haring wrote in his journal, “I’m not really scared of Aids. Not for myself. I’m scared of having to watch more people die in front of me. Watching Martin Burgoyne or Bobby Breslau die was pure agony. I refuse to die like that. If the time comes, I think suicide is much more dignified and much easier on friends and loved ones. Nobody deserves to watch this kind of slow death.” Haring died of AIDS-related complications on February 16, 1990; Halston died of AIDS-related cancer a month later. Of those Breslau was closely associated with, Burrows alone survives. What a giant loss.

Breslau’s dream for his life was “to be happy, to do beautiful things, functional, practical things of quality that last, that are nice to play with, that are sensual to feel, like Elsa’s jewelry.” While he definitely did achieve that in his lifetime, there is no recollection of his influence in the many soft, deconstructed bags available today. On the walls of Bobby’s studio was a letter from Diana Vreeland: “I’m sure you’re going to go further and further into the wonderful world of design. You are to leather what Cellini was to gold!” Imagine what he (and the many other designers who passed away from AIDS-related causes) could have achieved if they had lived longer (and if the industry had been more supportive to creatives).

Pulling together this newsletter, it is clear that is what is most missing is a sense of Bobby as the fun-loving, full of life individual so beloved by his friends. I’d like to interview those who knew him and gather more stories, possibly clean up some of the inconsistencies (though memory is subjective and murky, so interviews might instead provide more origin stories and more vantage points on his rise). There is a hope that by recording these stories that they won’t disappear. Phillip Picardi pulled together a wonderful oral history of the fashion industry’s response to the AIDS epidemic for Vogue, and there are many oral history projects focusing on AIDS (such as ones run by the New York Public Library, UC Berkeley and ACT UP).

More on Joe Eula later this week on the paid edition of this newsletter. Please comment or email for any citations or information on quotes.

- Laura

A whole generation of creative geniuses was lost in such a short period; an invisible war that took so many young men. It was the end of bohemian culture in San Francisco, as the gay contribution, in retrospect, was a keystone of a creative, alternative edifice. It was also the end of the Left as a vital political force, as the next generation of gay men were no longer such outsiders after the concerted agitation to cure AIDS, and queer culture was absorbed into the mainstream. There are of course pockets of queer Left resistance to Capitalism’s excesses, but it wasn’t until they were decimated that it became clear (to me anyway) the importance of ‘outsiderness’ to critical political thinking and alternative movements.

It’s not much discussed but from the vantage point of a native San Franciscan, the tone of the city’s underground, and its omnipresence here as a recognized character of the city, nearly evaporated with AIDS.