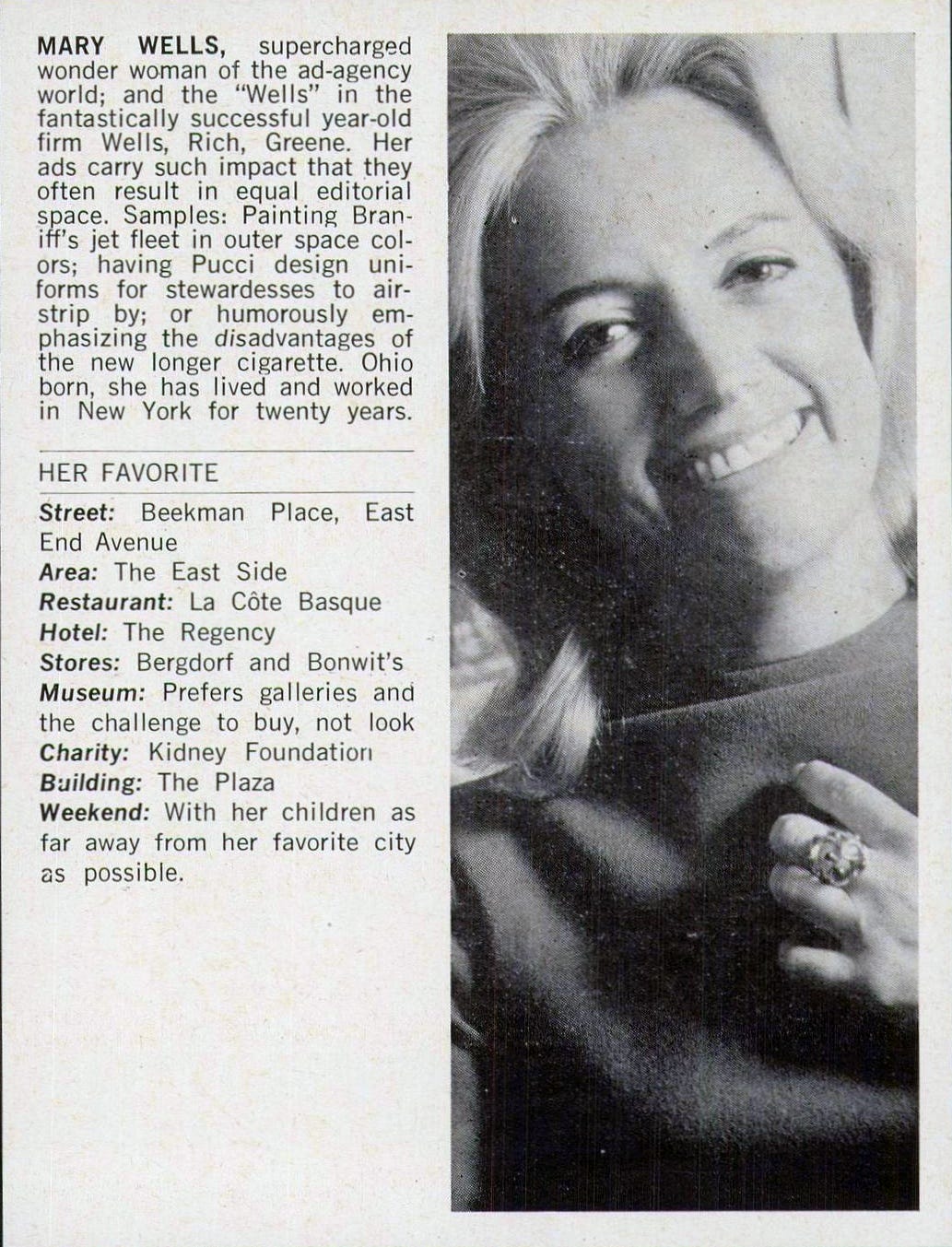

In the mid-1980s, Vogue interviewed Mary Wells Lawrence, then one of the most successful female executives in America, about business dressing for women. She began by explaining how, when she was starting in the 1950s and 60s, the business world was a masculine world: “Rather than choose the route of being a fighting feminist, I chose to make men comfortable with me, so they would stop thinking about whether I was a woman or not. I wanted my sex to disappear. And so I have always used fashion in my business life to create an image and an atmosphere that are comfortable. I’ve never been too masculine, and I have never been sexy/feminine; I’ve carefully been ladylike. I’ve carefully looked as much as possible like somebody a male executive would be comfortable with in a sister or a wife, so that he stops seeing me. I’ve wanted him to work with me, not be uneasy because I’m a woman.” Though this restrained ladylike image was her ethos for dress, what Mary Wells Lawrence wore is far more interesting than would be presumed from that. While I shared the other day about her start in department store advertising, today I will be discussing her own clothes.

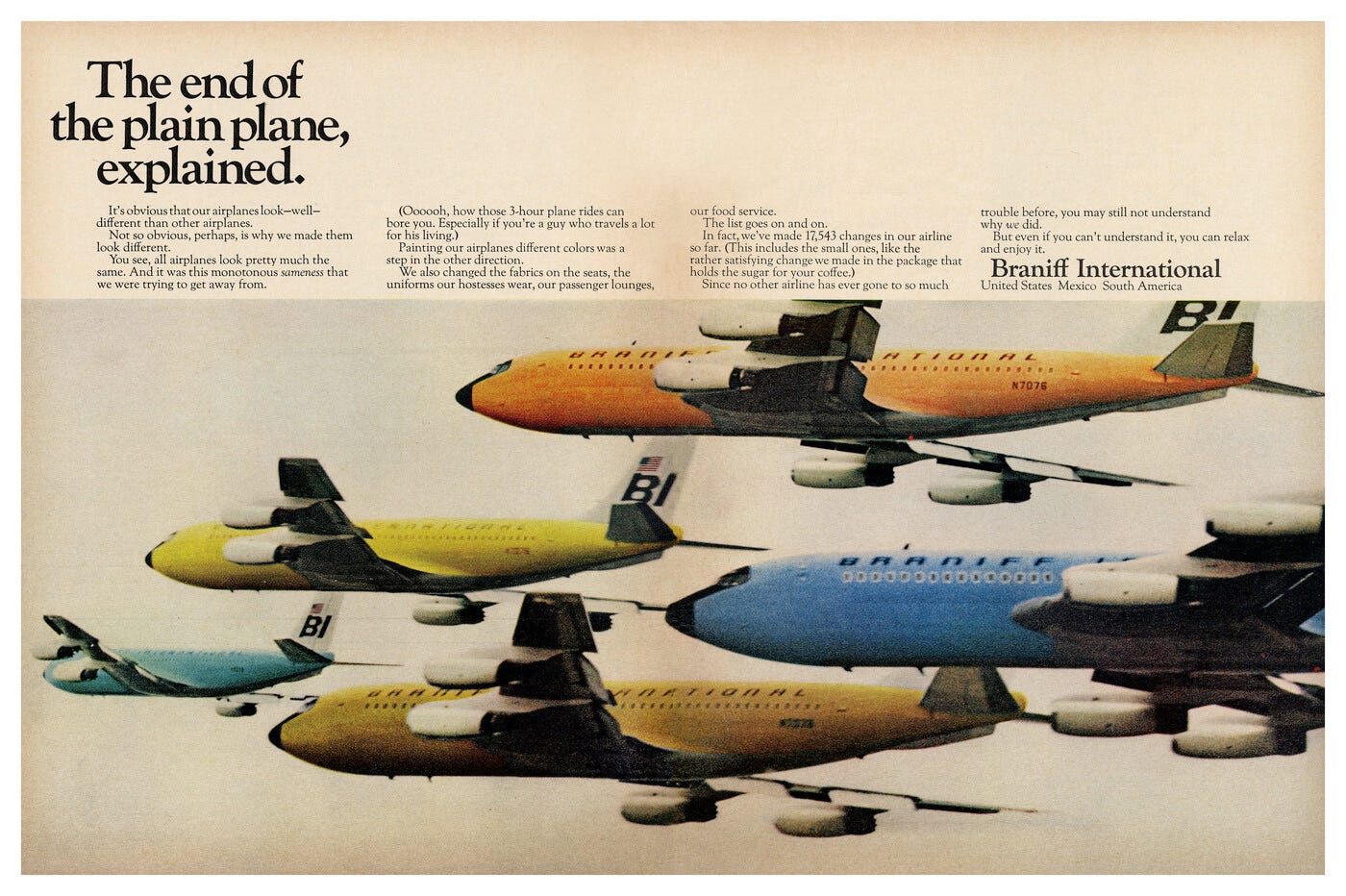

In 1953, Wells left department stores and moved into working for advertising agencies—a world she would stay in until she sold her agency in 1990. Wells’ most acclaimed advertising campaign—the one she is still remembered best for and the one that first brought her major recognition outside of the advertising industry—was for Braniff International Airlines. With a new president, Harding Lawrence, a new fleet of planes, and new destinations, Braniff was desperate to gain attention and more new customers. They hired Jack Tinker & Partners, a subsidiary of the advertising giant Interpublic, where Wells worked at the time. Fresh from Alka-Seltzer’s “Plop-plop, fizz-fizz,” Wells was tasked with working with Lawrence and Braniff; he told her, “I need a very big idea for this airline, something so big it will make Braniff important news overnight.” After touring their terminals and planes, she was dismayed by the drab colors, uniforms, and spaces. Her response was to soak everything in a “wash of beautiful color.” Wells hired Alexander Girard to redesign everything—and when I say everything, I mean everything; Girard implemented over 17,000 design changes in total. This was everything from the outside of the planes—now painted fully in one of seven exterior paint colors: yellow, orange, turquoise, dark blue, light blue, ochre, and beige—each with a black nose, white wings, and white tail. He redesigned the plane interiors, logo, ticketing areas, airport lounges, blankets, dishes, and more—all in bright colors and patterns that made Braniff stand out from all other airlines.

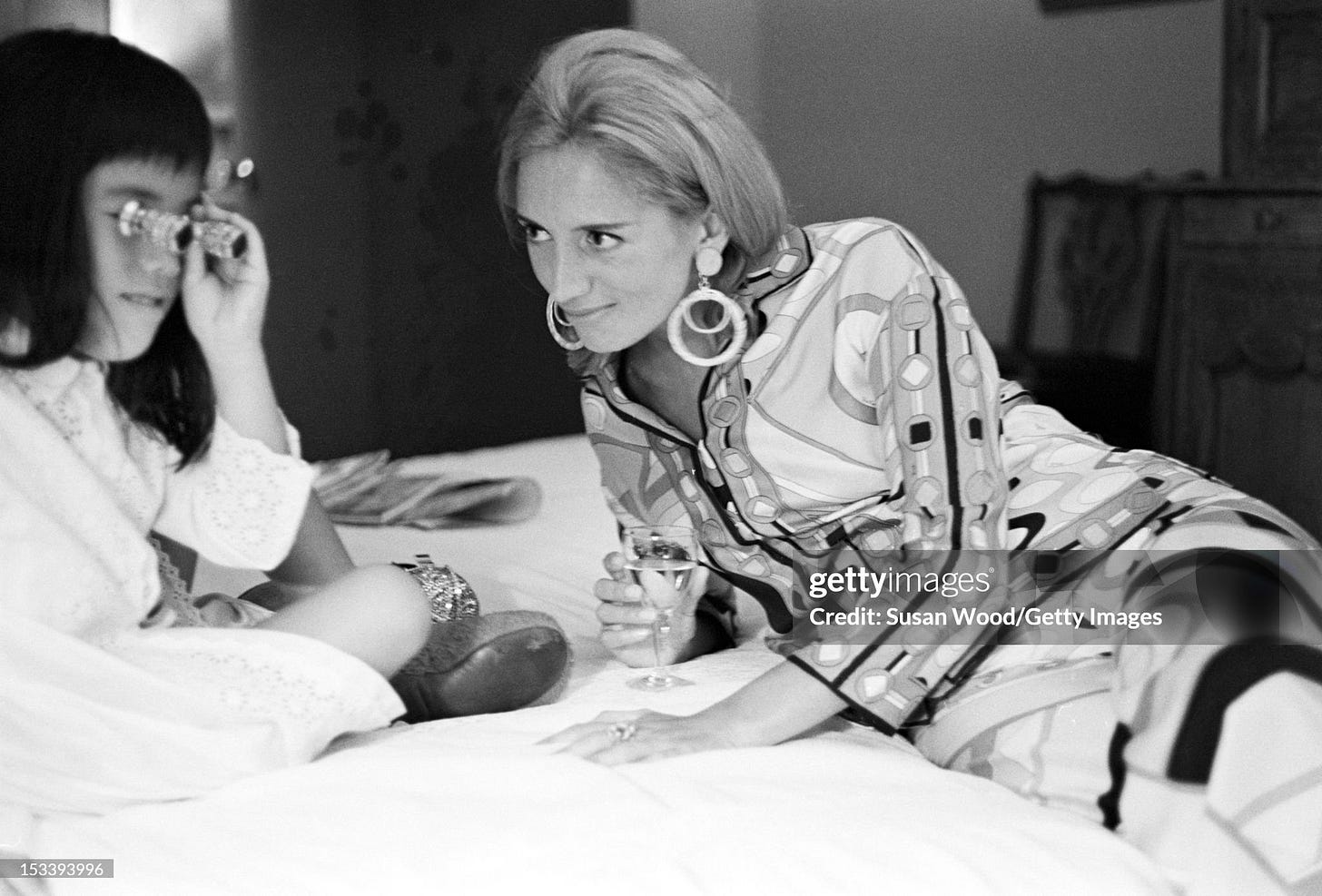

Wells also brought in Emilio Pucci to design the uniforms for Braniff pilots and flight attendants. When Pucci’s multi-piece stewardesses’ uniform that came off in layers during the flight—an “air-strip” as Mary cleverly termed it in the ads—launched in 1966, they made her into an instant celebrity and the hottest advertising talent in America. Photos from this period show her blond hair bobbed, with minimal makeup, wearing chic knee-length sheaths—except when hosting blowout parties for Braniff in Acapulco, where she wore Pucci, of course.

Not only did the Braniff job bring her fame, but also a new job and love. When Tinker/Interpublic refused to give her a promotion, she left and founded Wells, Rich, Greene; she was chief creative and president. Within months, WRG had scored the American Motors account; Wells wore “black and white windowpane check and low heeled black patent shoes” to announce the coup in Detroit. While she was making big moves in business, so she was in her personal life: as they worked alongside each other on the Braniff redesign, Wells and Braniff’s president fell in love.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sighs & Whispers to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.