"You must have the words, you must produce the magic": Mary Wells Lawrence

Advertising for Department Stores, 1948-1952

Advertising legend Mary Wells Lawrence has long been one of the women I was desperate to interview. Chic, innovative, creative, and a true businesswoman, Lawrence was one of a kind. When she passed away at 95 this May, the New York Times obituary headline described her a “High-Profile Advertising Pioneer”; not only was she the first woman to own and run a major national advertising agency, but in the 1970s she was the advertising industry’s most highly paid executive. “Arguably the most powerful and successful woman ever to work in advertising,” there has been much written about the many advertising firms she worked for and the many legendary campaigns she wrote [for the short version, read her NYT obituary; for the long, her 2002 memoir, A Big Life (in advertising)]; instead, I wanted to focus here on other aspects of her career and life. Today I will cover on her work with department stores, and this weekend on her wardrobe.

Mary Wells Lawrence’s (née Berg) early years writing advertising copy for department stores can truly be seen to lay the groundwork for the creativity and verve that brought her fame and fortune in the late 1960s and 70s. Fast-paced with large quantities of products and huge overhead, writing advertising copy about clothes for large department stores required a quick, problem-solving brain—one that could rapidly figure out how to talk about a garment in a way that would draw crowds into the store. A brain that could figure out how to do this on repeat, every day of the week, about endless amounts of clothes, on advertisements that filled whole newspaper broadsheets. Throughout her memoir, Mary recalled her time working for four different department stores and the impact they had on her; not just providing her with her first advertising job opportunity, but also “how to create a climate on a newspaper page that attracts an experienced customer; how to be interesting, irresistible, haunting so that customers cannot forget an idea you have given them; how to create a recognizable style for a store, how to build a strong and lasting image.” Her memories provide a window into the backrooms of mid-century department stores—the mess, the good and bad bosses, the infinite piles of products.

“Of course, I’m a legend. But it’s not because of any great gift I have. It’s because I’m a risk taker.” - Mary Wells Lawrence, 2002

From Youngstown, Ohio, Mary Berg worked as a teen selling hats during the summers at McKelvey's department store. After studying for a year at the Neighborhood Playhouse School of Theatre in New York, she transferred to the theatre school at Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, where she met and got engaged to Bert Wells, an industrial design student. As they planned to marry and move to New York as soon as he graduated, Mary left Carnegie Tech after two years, moving home to work and save money for the relocation. Looking for work, she returned to McKelvey’s. Though it was not her plan, she found work in its advertising department, setting her off a career that would ignite her creativity and passion. In her memoir, Mary details her time working in the department store and the impact it had on her:

Vera Friedman was running McKelvey's advertising department and needed a writer. She said she hired me because I had theatre training and could type—the perfect combination of resources, she thought, for a trainee copywriter. In all the years that young people have asked me how to become a copywriter in an advertising agency I have always told them to get a job writing for a department store or another retail business. I still think that is the best place to learn about advertising, because it puts the problem so clearly before you. How do you persuade people to buy a store's pants and shirts, pots and pans, with only a few words in a newspaper? How can you find, how can there be, a few words so powerful they will make somebody get up out of their chair, pull out their Amex card and buy the pants or shirt that you want them to buy? There is something mystical in the process. There are so many pants, so many shirts, so many things being sold out there—how you can put 10 or 20 words that will lead buyers to your pants or your shirt in your store? In a department store you learn how to persuade in a few words. You learn from the buyers themselves, their necks are on the line. They must sell pants and shirts day after day after day or it is over for them. They are heatedly dependent on those words you write for the newspapers. The buyers don't have the words. You must have the words, you must produce the magic. You get so you can feel a buyer's pulse—it becomes your pulse. Any languid ideas you may have had are quickly dumped.

Picture it. All over America copywriters are writing words so powerful they make people stand up and go to a store and buy pants and shirts. From the first minute I loved the challenge of motivating 500 people I couldn't see, and who couldn't see me, to buy 500 pairs of $8.95 wash slacks within 24 hours of when the newspapers hit the streets. There is a dynamic in this challenge that is essential to absorb if you want to succeed in advertising; it is an intuitive line between you and the store buyers and the shoppers. You've got to have it—even later when you are a big star, computing frogs to sell beer on television, you've got to have it. The best place to develop it is in the retail business, a relentless wheel of buying and selling. Day after day after day after day you have to have the words. A success every week or every month is not enough. You have to come through with the words every day for every buyer who is counting on you.

Vera hired me to write advertising copy for the bargain basement floor of McKelvey's. The merchandise manager, who was a dictator there, was a short, muscled fellow with eyes that snapped at me like little whips. He wanted results and he didn't mean maybe. "Sale!" he would yell at me. "Say it louder." "SALE!" "No, say it bigger, louder." "SALE!" He thrilled me. It is impossible not to become intoxicated in a department store advertising department with so much riding on you.

Vera was educated, well traveled, articulate. She was married to Fred Friedman, the editor of the leading newspaper, who was involved in with local politics, and their dinner table conversations were bristling opinions and debates. They had no children, I would do just fine, she spent hours after McKelvey's closed evenings teaching me the fine art of advertising the store's tonier, upstairs fashions: how to create a climate on a newspaper page that attracts an experienced customer; how to be interesting, irresistible, haunting so that customers cannot forget an idea you have given them; how to create a recognizable style for a store, how to build a strong and lasting image. She was appalled at all the books I hadn't read, and to give me a taste of what I was missing, she persuaded me to tackle the Odyssey, analyzing Telemachus over tuna salad sandwiches at lunch.

Mary continues:

With Vera, at McKelvey's, I was a puppy, ardent with ideas, and I gave her headaches. I heard about the Dallas newspapers with their Neiman Marcus ads. Neiman Marcus advertising in the fifties was the creme de la creme of department-store advertising. It was world-class retail advertising, smart and amusing and an eye opener for me. It made me try to get that same sophistication into my ads for the bargain basement floor of McKelvey's. The merchandise manager would always hit the ceiling and go howling to Vera. "Where does she get these ideas?" he asked her morosely. "Where does she think she is, on the Champs-Elysées?" Vera carefully reminded me that Neiman Marcus style was an inappropriate way to sell pants from a place people counted on to charge the best price. She pointed out that their particular dream was to find a great bargain. She taught me to imagine and sympathize with the people who were the customers for McKelvey's bargain pants and shirts, to put myself in their place, to imagine their lives, to talk to them and not to myself; she made me understand that they were as exciting and meaningful a target for McKelvey's as the women who bought expensive fashions in the upstairs store and that the customers who had precious little money were an even greater challenge than the rich ones. They had more suitors. They had learned to be discriminating. So if I won their trust I had achieved something to be proud of. Vera taught me to be a detective and a psychiatrist before allowing myself to be an artist With the few words I had to persuade people to buy from me.

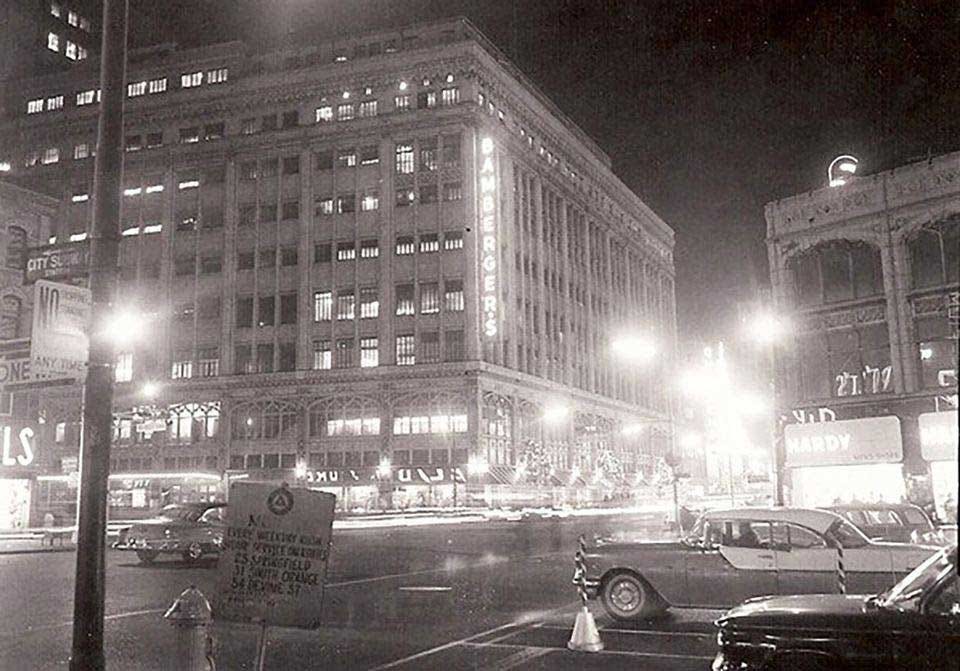

When the Wells’ married and moved to New York in 1949, Mary found work immediately at Bamberger’s in Newark and then at James McCreery Co., a department store on 34th Street (it closed in 1953 after 116 years). After a year, she was headhunted by Macy’s: “…when I was hired by Nan Findlow in the grand advertising department at Macy’s for what seemed like a fortune to me, it was as if I had climbed Everest, I was sure I would never, ever leave.”

For Mary Wells, Macy’s was instrumental to her becoming the advertising genius she was later hailed as:

Macy's was a profoundly professional place. It was no training school, you were expected to know how to deliver results demanded by some of the world's shrewdest buyers. I was honored when I was promoted to copy chief of the fashion division. Macy's copy chiefs were responsible not only for a buyer's ultimate success, but also for the accuracy of each ad when it appeared. If you made a mistake and advertised a dress for $9 that should have been advertised for $99, the responsibility was all yours. The guillotine sat in an office nearby—the supreme advertising manager, a big executive at Macy's and a man with no jokes.

I don't remember Macy's advertising department ever being cleaned; it had the aura of a busy newspaper office, the clacking of typewriters, the dull shine of cheap olive metal desks, large dusty windows, the left-over smoke of old cigarettes, precarious stacks of papers and myriad forms all over the place, they just collected and grew. You knew that one day the people would move, not the stacks of papers. Every area had a domineering wall clock and none of them told the same time. Still, there was nothing emotionally disorderly about the place, it was self-disciplined and self-important. Thousands of dresses, hundreds of thousands of white shirts, untold numbers of underpants and socks were sold there, millions and millions of dollars were made in that advertising department.

Every day, starting very early, I met with the buyers on the different fashion floors. They would show me what they were planning to advertise and they would give me information about it, they would sell me on it.

It was important to them that I see the appeal of what they had to sell and to understand exactly whom they bought it to sell to. They wanted me to see that what they had to sell was a jewel and I always did, I always saw their dresses or coats or shoes as transcendent offerings. I became such an enthusiastic, understanding partner for them that in time they trusted me, they even trusted my instincts about what they should choose to advertise, they would call me at home night after Macy's closed to get my opinions.

I really adore the way she talks about fashion and dress here:

Fashion was prospering in the fifties. Times were good, people had money to spend and they were enjoying new clothes. It was then that I began to theatricalize what I sold. Life is, after all, the way you see it. I began to see the dresses and coats they brought to me as potential dramas. It wasn't enough to just describe them accurately. I needed to make them important and meaningful. If they brought me a plain grey dress, for example, I would see that the grey dress was a far more exciting basic dress than the basic black dress that every woman already owned. I would write that the "little grey dress" was the rage with smart women who knew about such things and that this little grey dress in particular was the one to wear.

If they brought me a coat with a mousy fur collar, I transformed it into the new way to wear fur—quietly, like young royalty. Flat shoes became “just like Audrey Hepburn's." When we received a carload of jackets that were all the wrong size, extra-large, and the manufacturer went out of business at the same time, I persuaded the buyer to take a full-page ad in the papers and I sold the whole lot by announcing that the hot Parisian jacket for winter had arrived, I named it the Souffle Jacket, and said it was blown up, divinely out of proportion, as only the French could do, to make you look thinner, fashionably skinny, underneath. The women who bought those coats felt stylish in them, so they looked stylish in them, were stylish in them. Fashion is about sacramentalizing the ordinary, it’s about wearing your dreams. I grew to see that everything for sale on the fashion floors at Macy’s could enlarge a woman's life if I created an idea, a drama for it. That, I realized, is what fashion advertising and marketing are supposed to do—enlarge someone's life through her or his imagination.

Of the department stores she worked, only one company still exists (Macy’s), and of the actual buildings, Macy’s Herald Square is the only one still a department store; McKelvey’s in Youngstown was demolished in the late 1990s, Bamberger’s in Newark is a telecommunications hub, and McCreery’s on 34th Street is now the Amazon headquarters.

More on Mary and her style this weekend.