The Prince of Chintz: Emily Evans Eerdmans on Mario Buatta

Interior Design in the 1980s and English Country Style

After around three months, I am back from my maternity leave and so ready to return to sharing moments of cultural history with you. I will restart paid subscriptions today with the first paid newsletter being sent out this weekend, returning to my usual twice-weekly schedule of one free and one paid—upgrade your subscription to receive all my newsletters.

Growing up on the Upper East Side in the late 1980s, Mario Buatta’s influence was everywhere around me—at friend’s apartments, the fancy drawing rooms we weren’t supposed to play in and the fancy bedrooms we were. Chintz was the fabric of choice for the “English Country House” style Park Avenue duplexes and triplexes, whether designed by Buatta or one of his acolytes. When I moved to London in 1991, I became acquainted with the origins of his taste: Nancy Lancaster’s Yellow Room, John Fowler of Colefax & Fowler, endless National Trust manors (as redecorated by Fowler)—at 9, I even designed my bedroom with dark green walls and rose-and-leopard print chintz curtains (it was a truly great room).

For me, Mario Buatta’s overblown, chintz-heavy, maximalist traditionalism—all “bows and bow-wows” (dog paintings)—will forever be incredibly nostalgic. I was overjoyed when I heard last year that Emily Evans Eerdmans, a design historian and close friend of Mario’s, was publishing a new book on him, Mario Buatta: Anatomy of a Decorator. Eerdmans worked with Buatta on a mammoth monograph that was published in 2013, Mario Buatta: Fifty Years of American Interior Decoration, but as she explains below, it was very much the book he wanted, not the book that she felt as a historian best told his story.

Following his death in 2018, Eerdmans was tasked with organizing and selling off his estate. That process led her to build his archive and write the book she had always wanted to. Whereas the first book is truly a showcase of wonderful images of Buatta’s interiors, Anatomy of a Decorator reveals more of his rags-to-riches story—from Staten Island Sicilian immigrant family to designing billionaire’s homes—while also delving more deeply into his design process and rules.

The early biographic chapters also include mini-biographies of decorators who impacted Buatta, as inspiration, mentors, or bosses. The inclusion of photos of rooms by these interior designers creates a visual timeline for the evolution of Mario Buatta’s style—each designer and space contributing a small element or a larger understanding of proportion, which coalesced into his own take on “English Country” style.

In addition to writing books on design luminaries like Madeleine Castaing, Henri Samuel, and Mario Buatta, Emily Evan Eerdmans also runs a multi-pronged design advisory from a stunning Greenwich Village townhouse she designed. The townhouse is a venue for exhibitions and a fantastic holiday bazaar (get on their mailing list for invites). As an art and design advisory, Eerdmans offers collection building and collection management services, alongside estate planning and decorating consultations.

I spoke with Emily in May when I was newly postpartum and slightly out of my mind, but I hope my love for Buatta and chintz shines through. Follow Emily on Instagram to find out about upcoming exhibitions at her showroom-home and the renovations of her lovely house in Maine.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Laura McLaws Helms: I have several of your books and then when I saw that you were doing this one, I immediately pre-ordered it, read it, and really enjoyed it. I loved the way you pulled together all these different threads and filled it out with mini-bios of all the decorators that he was connected with. You placed him within this larger universe of interior designers in America and Britain. It was really fascinating to see the connections.

How did you first meet Mario?

Emily Evans Eerdmans: We first met, or I should more accurately say I first met him, but he was not aware that we were meeting—I had just moved to New York, I had gotten my master's from Sotheby's Institute in London, where I developed this passion for 18th century English furniture. I worked for one of the top 18th-century English furniture dealers in New York, as one does, and we would exhibit in the Winter Antiques Show. Mario was no longer the chairman. He had a reign of terror there and was removed, but opening night was still very glamorous.

There was this one woman called the Baroness, and I think they said that she came from the White Shoulders perfume fortune. She had this Titian red dyed hair, and she always wore her emeralds. It was like, "Oh, there's the Baroness and her emeralds." People weren't wearing black tie, which I think maybe at one time they were, but it was really a thing.

Even though he was no longer the chairman but had been for decades before, you would see, that was when I first became aware of him, that he was there. He would have a dollar on a string that he'd be dragging around. Then you've got people in their emeralds and Mario's with a dollar on a string and Martha Stewart's trying to pick it up, or he's got weird crazy Harold or a weird toupée. That was part of Mario’s shtick—the whole Harold, his [toy motorized rubber] cockroach. It was taking Harold to fancy Park Avenue places and almost like putting a thumb in it, like, "Oh, here's a cockroach," taking the piss out of it. That was a part of his humor.

Anyway, that's when I became aware of him, like who is this man with a dollar on a string that everybody seems to be really deferential towards? I grew up in the Midwest. I didn't grow up knowing about him… My mother, I think, knew who he was, but having studied in England, I developed a passion for Colefax & Fowler in particular and English country houses.

The second time we properly met, he also wouldn't have remembered. This antiques gallery I was working for was celebrating their 40th anniversary and they wanted to do a book. My family's in Christian publishing, so glamorous, and it's academic, so there's not tons of money in it. Anyway, through my uncle who went to school with the head of Rizzoli, I got a conversation with the gallery in Rizzoli to have it not be a vanity publication, but to have it be a proper book. The gallery let me write the book. It was my first book ever [Classic English Design and Antiques: Period Styles and Furniture, 2006]. It was the book that I had wished for when I was at Sotheby's to learn about the golden age of English furniture. It was such an opportunity and the gallery was so generous to let me do that.

The gallery had a PR woman for the book. She also had done PR for the Winter Antiques Show and she knew Mario very well, Marilyn White. She brought Mario in to write the introduction to that book. I remember he came to the gallery and he was about to work on his last ever Kips Bay Showhouse room, the one that has had the green velvet walls. He picked out a mirror to borrow for the room—it went over the mantel place. That's when I first properly met him. I was so deferential. It was like, "Oh, Mr. Buatta." I was very formal and respectful, and he didn't like that. He didn't even notice me, basically.

Then people have been trying to get Mario to write a book forever. Now if you're a designer even for a month and you've just graduated from high school, you have to do a book. It's almost like an advertising brochure thing. It was starting to become really common for designers or decorators, as Mario called himself, to have books by the time Charles Miers at Rizzoli got Mario to do it. It was like years to convince him. I think we started around 2010, sitting down every day. He would just talk and talk and talk.

That's a four-year gap between when we really met for the Hyde Park Antiques book, and then when Charles suggested me as one of the possible writers for Mario's book. By then, I had done Regency Redux (2008) and I just finished Madeleine Castaing (2010). I didn't really want to help people write their own books, that was never an aspiration of mine. I like to do my own books and consider myself a historian, but I loved everything that Mario loved. I also thought he is somebody who really deserves a book, unlike so many people. He's got this important canon of work.

There were a few other people he was thinking about before me, but I don't think anybody else… It was like being in a rodeo and having to get, what is it, the cattle or whatever, the bull that's trying to buck you. I don't think many people could have stayed on the bull like I did with Mario. He was really needy. It was a really intense process because he wanted to sit down every single day for a year. That is not how these books usually work. You have a few interviews and then the writer goes off and then sends something.

Then even the editing process was a nightmare because Mario didn't have a computer, and he would call me and read aloud every single word of the draft and then scream at me every time he didn't like something. I'd have to listen to him read it. It was excruciating, it was really painful. Anyway, we spent a lot of time together. We really started to form a friendship, but I thought maybe he just wants me to like him [so that] I do a good job…Then we became—For me, it was a very profound relationship and friendship and mentorship.

I haven't had a lot of positive male figures in my life, I would say, and he really became an important one for me. He was surrounded by so many people who loved him and friends. Who knows what I meant to him, but he meant so much to me.

Laura: When you were introduced to him and his work, what was your immediate reaction to it? Were you a fan? Did you become a fan?

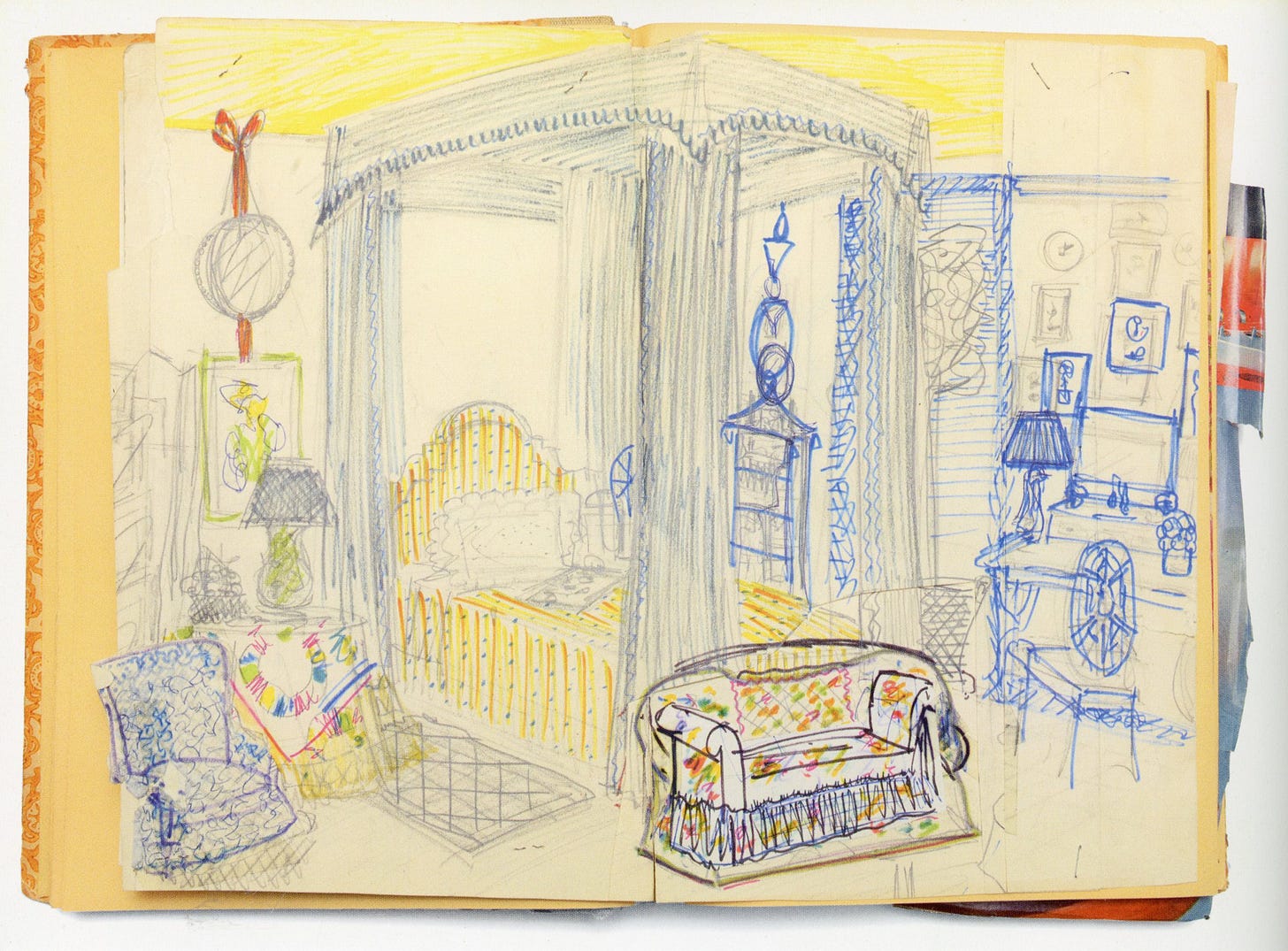

Emily: Oh, definitely. I think at first, it's that 1984 Kips Bay Showhouse room, that blue and white one where it just oozes atmosphere and it's romantic. Even though his early work is much closer to mimicking John Fowler's, it's a bit more restrained, less cluttered. Even in this later work, which is when he was at the height of his fame, the height of his career, you could still see that thread to Colefax & Fowler. Also, so many people have imitated that look and they just don't get it right, but he did. When you get it right, it's timeless. It's hard to put a year on when was that room made.

His color… I think that was a huge thing that really spoke to me. My family has a major depression that runs through. I don't know if it was in reaction to that, but my mother always painted our walls super colorful walls, cantaloupe and Robin's egg blue and lavender and deep brick red. Mario, I felt something in his rooms by seeing that embrace of color. Maybe when you turn the pages of a magazine you see color, but when you actually go out and visit people in their houses, especially in New York, a lot of people don't have color. It's almost a radical thing to really live with intense colors. There was just so much that we both shared.

I wasn't a super fan when we started, I have to say that. It was just that I thought this was going to be an important book—how interesting would it be to actually have your subject be alive and tell you how things really were? What I didn't anticipate, and I was naive, is it was his book. It wasn't my book like the other books. There were some really tough times when we shaped the story to be how he liked it, which I didn't find to be as authentic or there were people I wasn't allowed to talk to, things I had to put in there that I just thought gushy gobbledygook, but he felt he needed to. It was a weird experience.

I remember this magazine editor—her family is a client of Mario's and she adores him. She said to me, "This is the most important book you've ever done." Inside, I was like, "No, it's not," but, in hindsight, it was. My relationship with him… one of the biggest things that happened to me. She was right, actually. At the time I didn't really—It was like he deserved a book, and then the process was painful. Then how unrelenting he was and how meticulous he was with the detail, I started to understand that's why he was so good.

Laura: With the new book, did you feel like you were making amends for the things you had to do with the first one and you were able to fix the things that he had pushed through?

Emily: Right, exactly. I always knew there was another book, and I ended up seeing it as almost a companion to the first book. He was a favorite of Paige Rense of Architectural Digest, as I'm sure you know. She had a pact with her favorites that you were not allowed to be published anywhere else or else there'd be hell to pay. Almost his entire career was in Architectural Digest. Right around that time—things have totally changed at Condé Nast now—you were only allowed to have 30% of your book with Architectural Digest photos. It was like if 90% of his photos, how are you going to get around it? The new houses were very long-term clients of his, so they made an exception for him.

In a way, it was like the one shot. Because of the special exemption, it all went in. So many photos went into that book and it's over 400 pages. We really took it seriously how the second book could not be a repeat of the first visually but how to do that.

I always knew there was so much more to tell about his story that he didn't want in the first book at all. Like the real mechanics of how extraordinary that he had two or 1.5 semesters of college education, a family that is really Sicilian immigrants, not too well-off. How did he become the go-to designer to create old money looks for billionaires? That's insane, I think. He did it beautifully. That was the story I wanted to tell, but then another thing, he never wanted to share how he did things.

I just did a book event with Pat Altschul, one of his clients. She talked about how she went to a lecture he gave and everybody wanted to know how to do it, and he just wanted to entertain them and make them laugh and do a standup routine with his toupees. I wanted this book to really unpeel some of those layers of what are the elements of his style. I think he became such a jokester. I thought he wasn't taken as seriously at the end of his life that it almost had become a shtick. That was also important to me—I wanted him to have his place with John Fowler, with Billy Baldwin and the Pantheon of greats, to be more seriously considered. This book probably didn't need to happen for that. I think that would happen anyway, but just to put more out there.

Laura: Have you seen his career be reappraised in the 10 years since the first book and his death? Do you think people are looking at his work differently?

Emily: I'm so close to it. I think everybody was surprised by how successful the Sotheby's auction was—even Sotheby's, certainly. We had a contract structured on it making a certain amount; the estate wouldn't have to contribute if we made a certain amount, and I don't think Sotheby's thought we would really get there. I knew we would, and we did. Thank God we did.

Sotheby's said they couldn't believe how many younger people had walked through, so many designers that hadn't really been with them for a long time came back. It seemed like people were making a pilgrimage. It was what I dreamt and what I envisioned, but you never think—It happened. I can't believe the energy around that. It was really extraordinary.

Laura: With the Sotheby's auction, I know that you were involved, but what exactly did you do for it?

Emily: I was hired by the estate—which is basically his brother who just died a little over a year ago, who had Parkinson's and was not in great shape—basically to clean out all the spaces and sell everything. I had a contract with the estate to do that. I interviewed the various option houses, negotiated the contract. In addition, Sotheby's just took the tip of the iceberg. I was like, "Somebody has to take a thousand lots and Christie's refused to take that much, but Sotheby's would do it." That was a big reason why we went with Sotheby's.

STAIR Galleries, I think, took another, like maybe up to 3,000 pieces. I just knew these auctions were going to be our shot for the estate to maximize the return, but there was just so much stuff. There were four storage units, some enormous, some as big as an apartment, his Connecticut house was packed from floor to ceiling with a floor even caving in because of so much stuff, all these floors. The top floor, which was the attic, it just was boxes and boxes of stuff. I think he would say like, "Oh, I can't sell that house because I use it as a tax deduction for storage," and he really did store so much in there.

There was bat poop everywhere, mice, no electricity. There was one outlet that worked and we would snake one painter's light up three flights of stairs. Everything was moist, there was mold and everything. There was no bathroom. We would stay at a bed and breakfast that was used for wedding weekends. We could be there until Thursday. That's when the wedding parties would start to arrive. It was like, "Okay, I have a bathroom I can go to until this time."

It was so primitive and intense, and it was kind of amazing. I mean, it was a treasure hunt. I found all these George Oaks framed pieces, but sadly, they had become mildewed… things like that. He had bought the entire library of this fashion designer, Mollie Parnis. She had been a Billy Baldwin client, and he bought her entire library and, of course, most of it had been destroyed. She was very close to Dwight Eisenhower, and she had all this presidential stuff. [Mario] was all about collections, his rooms were about collections, and to just to really uncover what a serious collector he was—that was so cool.

Also, there's this granddaughter-in-law of Bunny Mellon who said, after her auction—because she had so much stuff and she was a hoarder too, but she just had so many buildings that she could keep it tidy—she said something like, "Oh, to see how much stuff she needed. It was like (I'm paraphrasing) filling a void.” And I definitely think that was part of the situation with Mario. It was fun, it was sport, but it was also filling something in him. He would say that when I said, "You have to sell that Connecticut house." I mean, it was about to collapse. It just was sold right in the nick of time. He's like, "You have Andrew," my husband, "I've got my stuff." He made a decision to not part with it, live a certain way, and I think he would have lived longer if he had been able to let go of it, but that's not the way he wanted to live. You have to respect that, right?

Laura: Yes. That sounds really intense. As a historian, there's nothing I love more than the digging, but it can also be incredibly sad and overwhelming.

Emily: I came across a cache of letters from John Fowler to Mario in the '70s and understood the relationship a little bit more. In those moments, I was so grateful it was me cleaning it out because it would have gotten thrown away. There was just so much stuff that if you had hired a firm to come and just clear away, it would have been trash. I did create this archive. I hope it can be donated somewhere—it's really up to the estate now. I'm out of control of that. You really understand how it made it maybe a slower process because every single thing, I was like, "I have to look at everything. I can't just throw something away because what if that unlocks the key to—" Not that he was a Nobel Prize scientist or something, but still.

That actually made this book the hardest book I've ever written because I knew things he didn't even want me to know about, that he wouldn't want anybody to know about. Then feeling protective and what is appropriate to be in this book, what isn't. I wanted to talk more. A really huge thing, and I mentioned this in an event I did in the South and you could just feel the whole room go sour, I think the AIDS crisis really was so traumatic for him and so many of other gay men of his generation. I think he was terrified to have a romantic relationship.

I've definitely been told about different boyfriends, entanglements, but nothing permanent. Never lived with anybody. He had a boyfriend maybe when he was like 23 that he was roommates with for like maybe six months, but that was it. There was this crazy article I found written by his client, Taki Theodoracopulos, 1985 or '86. Basically, he's like, "My decorator, Mario, he is so straight. He's as straight as they come and everybody thinks he has AIDS," he doesn't say AIDS. He says the big C or something, "but he doesn't. He just lost a lot of weight."

The fact that Mario would ask his client to put in a column in The Spectator, wherever it was that he was writing, to say that he didn't have AIDS just shows you how… Mario, when he turned 50, he got these speed diet pills to lose a lot of weight. That's how I can often date his photos. Like, "How skinny is he?" Like, "Oh, he's turning 50 there." People saw him losing all this weight in 1985 and thought he had AIDS.

There's this story about Bill Blass at One Sutton Place South, which is, as you know, a top building. He had to promise he would not have any overnight guests to be able to buy that apartment. I was told that Mario had to promise that when he bought his office space off the lobby of the building that he lived in, which Mario never shared with me. How mortifying is that?

Laura: It's so crazy that that wasn't that long ago.

Emily: It wasn't. It really wasn't. With those things… and the connection to his hoarding and all of that. It's just like this book wasn't necessarily the place to go quite into that in-depth, but I find it fascinating as an exploration of his personality. It's like what was appropriate for this book?

Laura: I think you brought in more of his biography than I previously knew. You managed to find a way to bring in [Mario’s past], especially his Staten Island childhood. I love the photo of, I think it's his aunt's house.

Emily: Oh my God, that was crazy going in there. I surreptitiously took the photos because I didn't know if the brother would be okay with it. He was fine in the end, but they're terrible photos. I was so grateful Rizzoli let me put them in. That house was insane.

The other thing that just reminded me of how extraordinary Mario was for his family was Aunt Mary had a daughter, Teresa, and she died two months after Mario. She still lived in her childhood home. These were two-bedroom houses. They were really, really small. She slept in the tiny bedroom, and the big bedroom, which was her mother's, was like a shrine to her mother. Mario's brother still lived in the house that they grew up in a block away. Is that crazy? Just not moving, not leaving. Parents live there, you live there. It's so unusual for most of us today where we're constantly moving, especially in New York, every year a new place. Then here's Mario. He was like an alien.

Laura: It really does show how dramatic his ascent was.

Emily: And how ambitious. He was the kind of person—I don't know if you had any, maybe you were like this in college—but they seem like a major party person, but then you catch them studying at 02:00 AM in the morning. They don't want people to know how hardworking they are. He was just like that, that he could [work] with hardly any assistance at all, and also, he didn't trust his assistants. He didn't want them to learn from him because he was paranoid about them stealing clients.

That he could take these incredibly detailed, huge jobs for super demanding people and keep it all going in his head and go out to parties every single night, talk on the phone constantly, which is why he was great with press, because he would always call back a journalist like that. It's crazy.

Laura: What would you say are the defining elements of his style? Obviously, we call him the “Prince of Chintz,” but the defining things of his style.

Emily: What your question made me think of is a lot of people think of him as the '80s. He's the maximalism, traditionalism of that period, but when he first resonated to Nancy Lancaster's Yellow Room in 1963, and he slowly was able to make that what his work was about and get to meet John Fowler and become friends with him, his peers were not doing that. It's like Angelo Donghia: sleek, sexy, streamlined. [Mario’s] actually going this other crazy way with colors and flowers.

There's this article he did with Interview Magazine in the early '80s where he talks about how people made fun of him, like, oh, his bows and bow-wows. His bows and dog paintings. People didn't really get what he was all about. Then he was perfectly positioned when there was this anglophile craze that erupted.

In that spirit of how Mario was almost rebellious in his traditionalism—which Madeleine Castaing was very much the same way in her time when she was going for this nostalgic style—I think his work, which is about joy, color, prettiness, making people look good and feel good, there's something rebellious about that. It's not intellectual, it's not curated, it's about comfort. I think people are afraid to say they like this style because it's like it's grandma, which actually now is chic, but I think what I'm seeing out on the road whoring out this book is a lot of people in their 20s, early 30s are saying that their parents rejected the Mario style. They're Jil Sander and Helmut Newton-ish in their lives, like black and beige and whatever, but the 20-year-olds and the 30-year-olds, are now into it. It's almost like this rebellion, pendulum switching. What do you think? I'm curious for your opinion.

Laura: Yes, I can see that. Especially on social media, I see more people being desperate for homes that have more personality. Because you see that white farmhouse look that's on every Pinterest board and magazine and HGTV, that's now the American style. I think that people are bored of it. I see people say like, "Oh, I don't think I could live with [colorful tradionalism], but I love the look of it."

I think some people are scared. There's a lot of people who are so used to some form of minimalism, whether it's actual minimalism or the white farmhouse look, that people are scared of [color], living in it. I think people are responding to it, at least, even if it's just a photo. I hope that the people a decade or so younger than me are starting to at least learn about the [more traditional] designers and seeking them out. People like Mario.

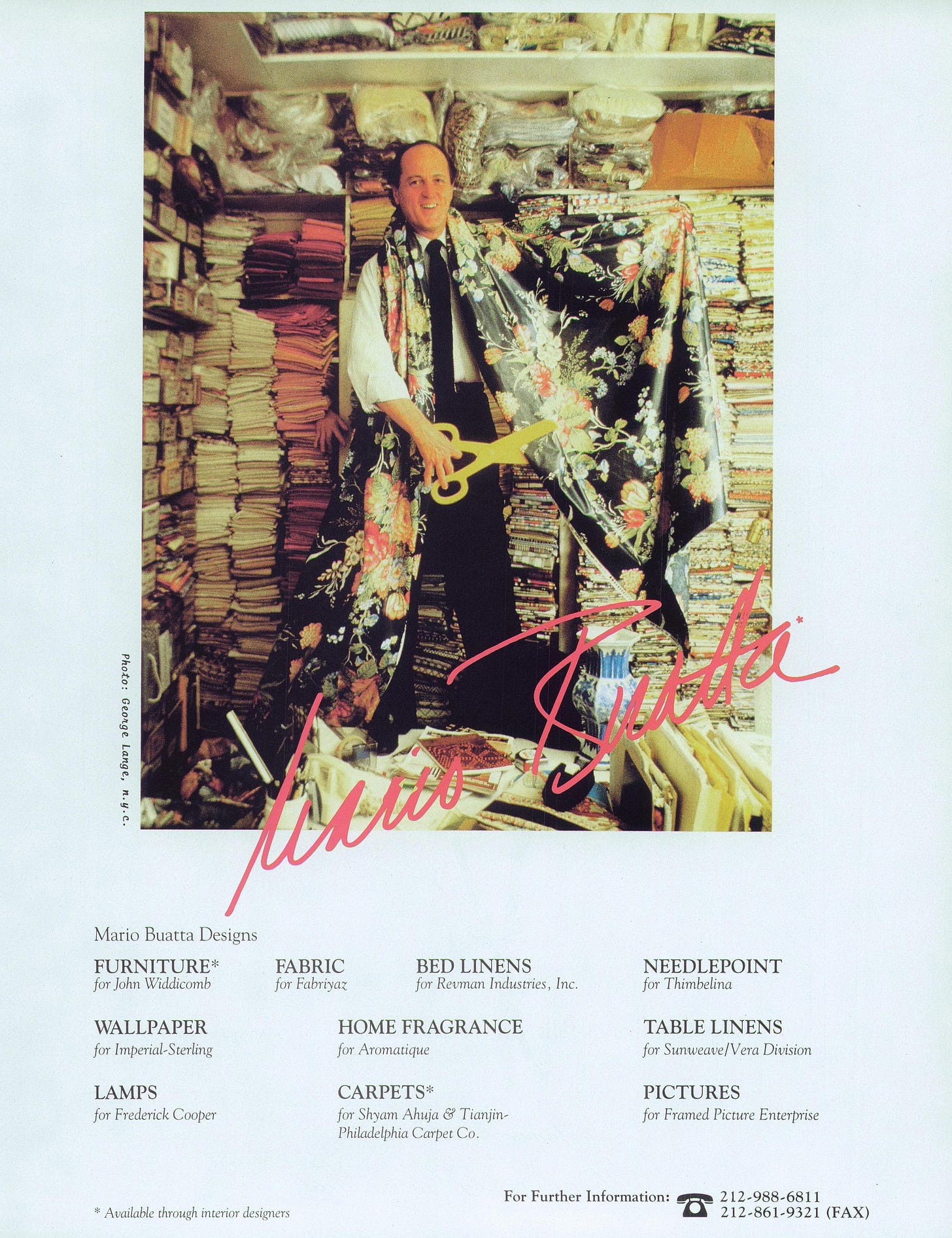

Emily: Yes. I think that's really true. Mario would have been made for social media. Everybody thought he had a PR person, but he didn't, but he was very good at making himself a personal brand… In Sister Parish's oral biography [Sister: The Life of Legendary Interior Decorator Mrs. Henry Parish II], they have her saying about Mario, “His name is on like potpourri and on this and that. He goes to every party. What's he about? Is he a designer or what is he?” She just didn't get it.

I think it really shows the generational shift. Sister Parish is this whole old guard WASP firmament that Mario desperately… He wasn't pretentious and he wasn't a phony. That was the amazing, that was like one of the coolest things about him and I think why his clients loved him. He knew he wasn't, and he never hid where he was from. He lionized that aesthetic and lionized the look of it. I think had a wistfulness about it. It was sort of like a Hollywood version of it that he was creating.

Laura: I loved learning a bit more about his licensing with the fabrics and things. I thought it was really interesting that you said that he didn't like them or didn't use them.

Emily: I had all these conversations and then COVID hit about doing a new fabric collection that he would have used. Then the brother wasn't really interested either, so it couldn't move forward. I just thought that's like such a shame that what he put his name on was just mass market and not what he would have actually used.

Laura: Definitely. I've seen the ads for the fabrics he put his name to before. Now, after looking through this book, I was like, “I really need to get some chintz,” but get some of the chintz that he loved. The ones he loved and used. Though I live in a very mid-century house, so it doesn't work at all.

How did working with Mario on his book and then the new book, and also all of your books, how did writing these books on these different designers influence your own taste and your own approach to designing?

Emily: I am now doing design work, which was not an aspiration when I moved here in the year 2000 when I moved to New York. One of the reasons why Mario's work was so good was because he didn't compromise on the details. It's the details that teach you so much. You also scrutinize for your work as a historian, lots of printed images from the past. That's sort of my favorite part of any book project, is just going to the New York Public Library and having them bring up 30 binders of decades of magazines. You just drink in the detail and then you absorb it. You absorb it more than you realize.

That's what I've realized doing design work, that like, okay, yes, there's a little Madeline Castaing, a little Henri Samuel, a little Mario, and a little me, and the client of course. The one thing that they all shared and had in common that a lot of people might not realize, and I try to put it in this book, is the importance of getting the architecture right before you do anything. It's sort of like, do you need to move a wall? Do you need to make a door case higher? Are the moldings appropriate? I think a big thing, everybody else I've written about has been European. Really like a big part of this book is contrasting Mario to Colefax and Fowler, there's a chapter on that. He scrapbooks with every single article he was published in, in addition to like articles about Sister Parish and other things that piqued his interest.

When I was going through the '70s, there were a lot of articles with him and Sister Parish talking about creating their look in American architectural spaces. Which are so different from European spaces in terms of proportions and moldings and all of it. Even pre-war spaces don't have the same tall ceilings generally, and don't necessarily have fireplaces or just sort of focal points that you would have in a European residence or domicile. That was something, made me think about that. Basically, Mario and Sister Parish's answer to that was curtains, like very architectural, elaborate curtains and upholstery, the importance of soft upholstery and huge sofas and club chairs. The pattern and the color that you put on those, how they built a room versus how John Fowler or maybe David Mlinaric or somebody else would do it in Europe.

Laura: Your townhouse is definitely one of those places that feels more European in its proportions in terms of the rooms. The high ceilings and the big windows.

Emily: Oh my God, yes. We just have the two floors here, not the whole townhouse. Oh, and I have to tell you, I remember, before COVID we lived on the ground floor in Brooklyn Heights of a townhouse and Mario would come over for dinner. I guess our ceilings, what would it be? Like eight feet or something I think would be standard. We thought we might live there forever. We didn't know. It had a great garden. Yes, we thought it was great. Mario is like, "Well, you're not going to live here forever." He's like, "Your ceilings are so low." When I saw Pat just a couple of weeks ago, she reiterated how high ceilings were really important to him.

I remember when we moved into this space and I now have 13 feet ceilings in one room and Mario only had 12. I was like, [laughs], "Yes, I beat him." Is that crazy? The high ceilings make such a difference. They really do. That apartment he had in that 1920s townhouse, that was essential to telegraphing his look. The proportions, that is part of the look, is having that.

It is interesting. He did this project for these Ohio clients—I think it was an apartment in Miami. It's in the first book. It's probably like some post-war glass building and like how he decorated it. He made it all really dark [laughs], like he glazed the walls and he's like dark gardenia green leaf colors. It's very moody, which I guess would have felt refreshing in Florida, but it also seemed a little oppressive. He wasn't the designer for everything and he owned that.

In the book I talk about how he really got his start, which was because of the suicide of George Trier and he inherited his clients. He would do anything they wanted. He really started off working a lot in New Jersey and whatever came his way, like he didn't have any financial backers, so he had to do it. When he really zeroed in on this Colefax and Fowler aesthetic, and pretty much when he did his first showhouse room in 1968, which was just owning that look. That's when he started to become successful. That's like one of my favorite lessons with him.

Madeline Castaing was very much the same way. There's like this clear vocabulary of color and pattern and you see a room and you can pretty much know they did it. Not trying to be everything. Whereas like when I was interviewing Jacques Grange for the Madeline Castaing book, because he was good friends with her. He was so proud that he wasn't like Madeline Castaing and that he was much more able to work in any design dialect. I think he's a rarity to be honest, to achieve the success he has. He does do gorgeous work, whether it's modern or traditional. I think for most people that doesn't work as even like a career strategy.

Laura: There are definitely some rooms that feel less “Mario,” but still have at least elements of his design vocabulary, whereas other rooms have every single one. Even the ones that have less, still have elements so you can see the through line.

Are you working on any new books or any new book projects?

Emily: The next one is on Robsjohn-Gibbings. This is a book I have been trying to write for over a decade and it kept getting canceled or postponed and he's never had a book done.

Laura: Amazing! He deserves one. I've always thought he deserved one.

Emily: He really does. He was really influential too in terms of the taste for furniture in America, and sort of the Scandinavian modern thing. As somebody whose background really is in furniture history, but like gravitated towards [talking] about the whole environment, I'm really excited about that. I think it's an important book. Ideally, my dream would be to somehow tie it into an exhibition, which I don't think there's ever been one on his work either.

That's sort of my next and then probably the last one I'll ever do. I'm finding it so much more fun and easy and creative right now doing design work. It's important to have different chapters in one's own career creatively.

Welcome back! I hope all of you are getting some form of sleep! Those first few months are rough!!!

This was so great, thank you! I grew up in Newport Beach, CA and this influence/style or “chintz” was certainly over here but with a bit of an “airy” California take (if that makes sense). Even my crib had a frilly canopy.

Also this reminds me of the film “How to Get Ahead in Advertising” by Bruce Robinson. It’s totally wacky but I love it (and Richard E. Grant for that matter. And obviously “Withnail and I” which they made together). Richard’s English house was the first thing that came to mind when I opened this post. If anything you have to see the blue and white kitchen in the film!

Laura, Love this... brings back personal memories of the 80's!