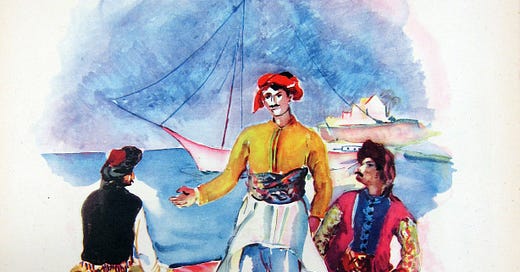

Georges Cyr's Lebanese and Syrian Costumes, 1939

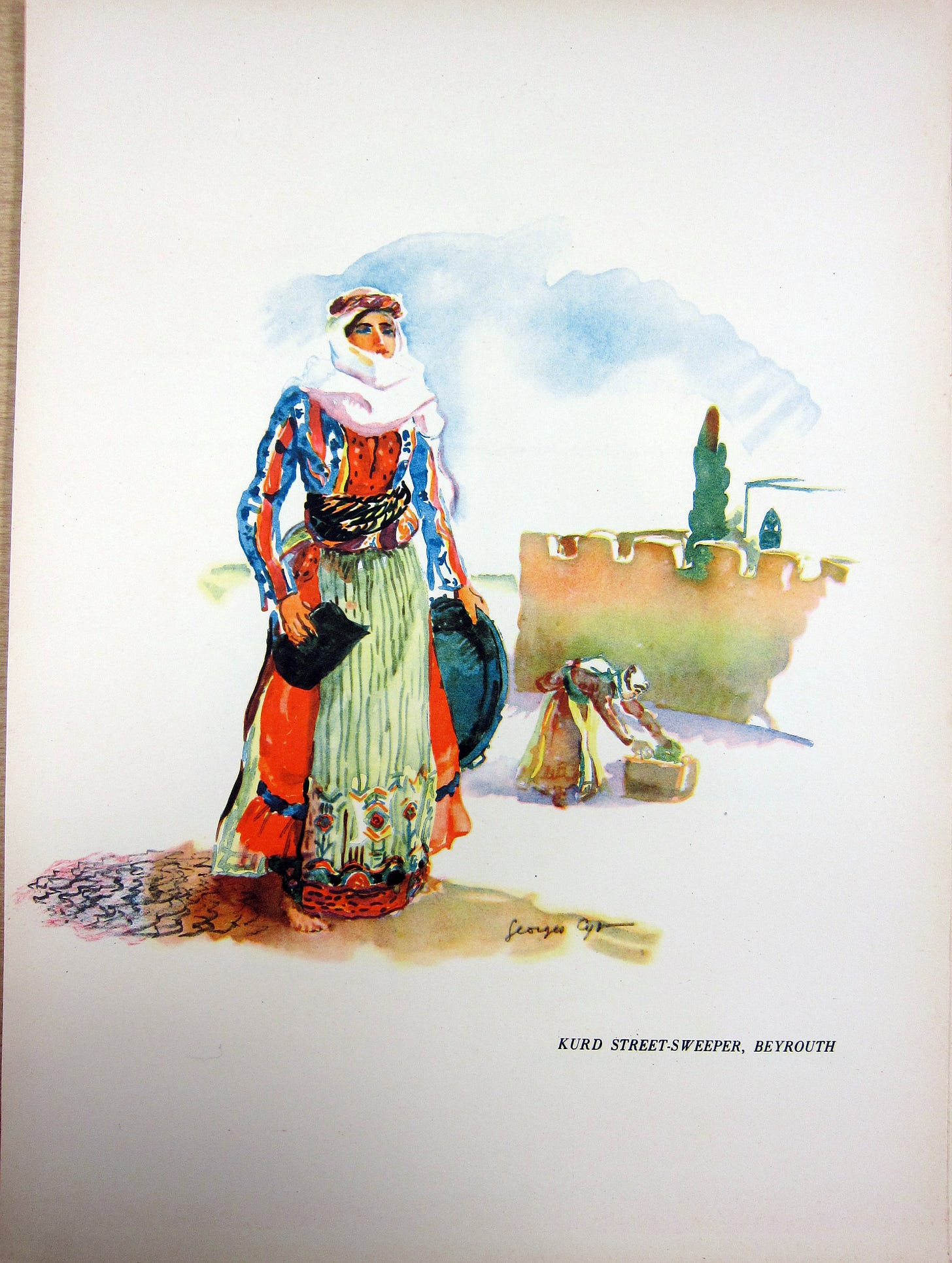

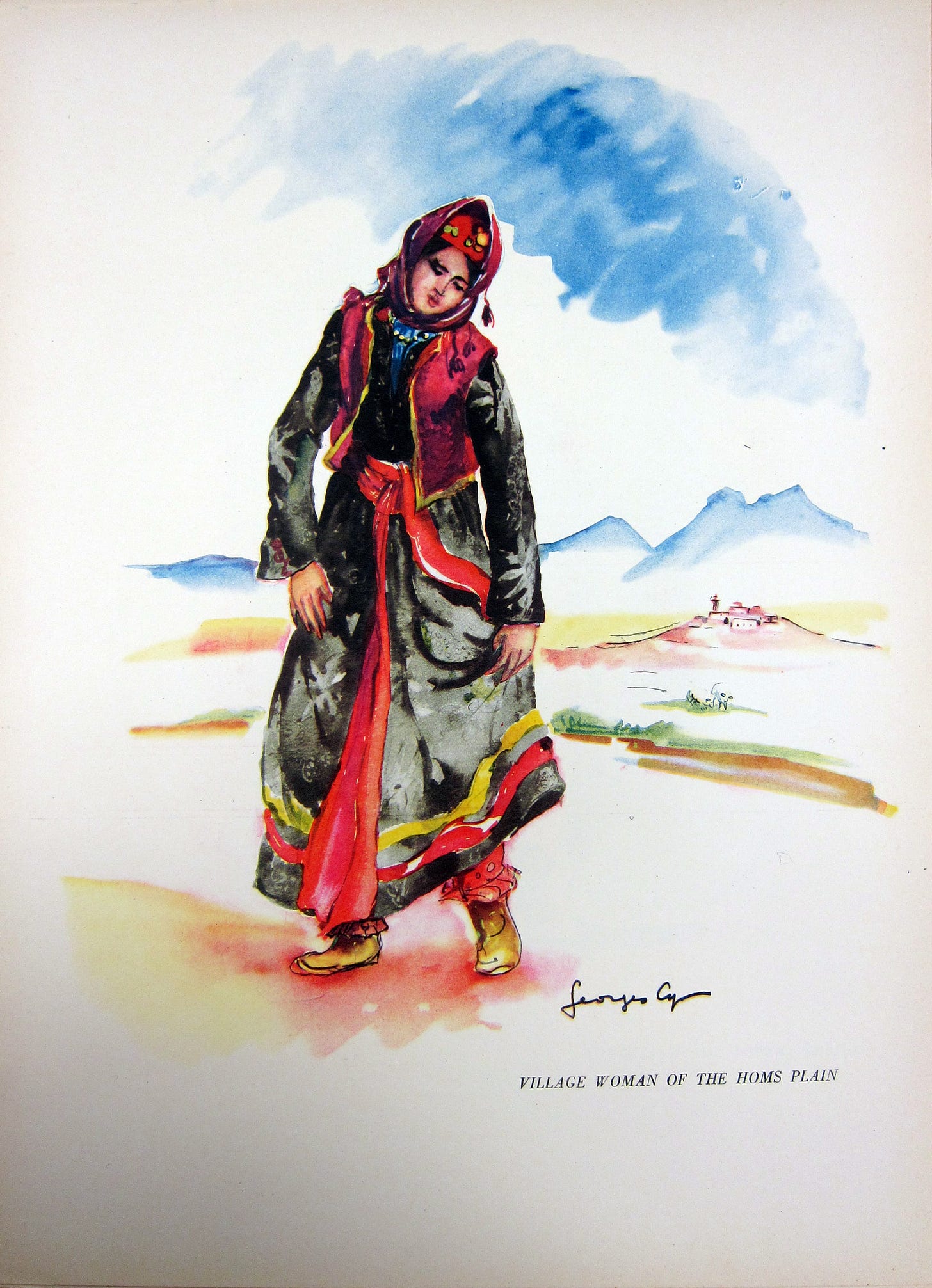

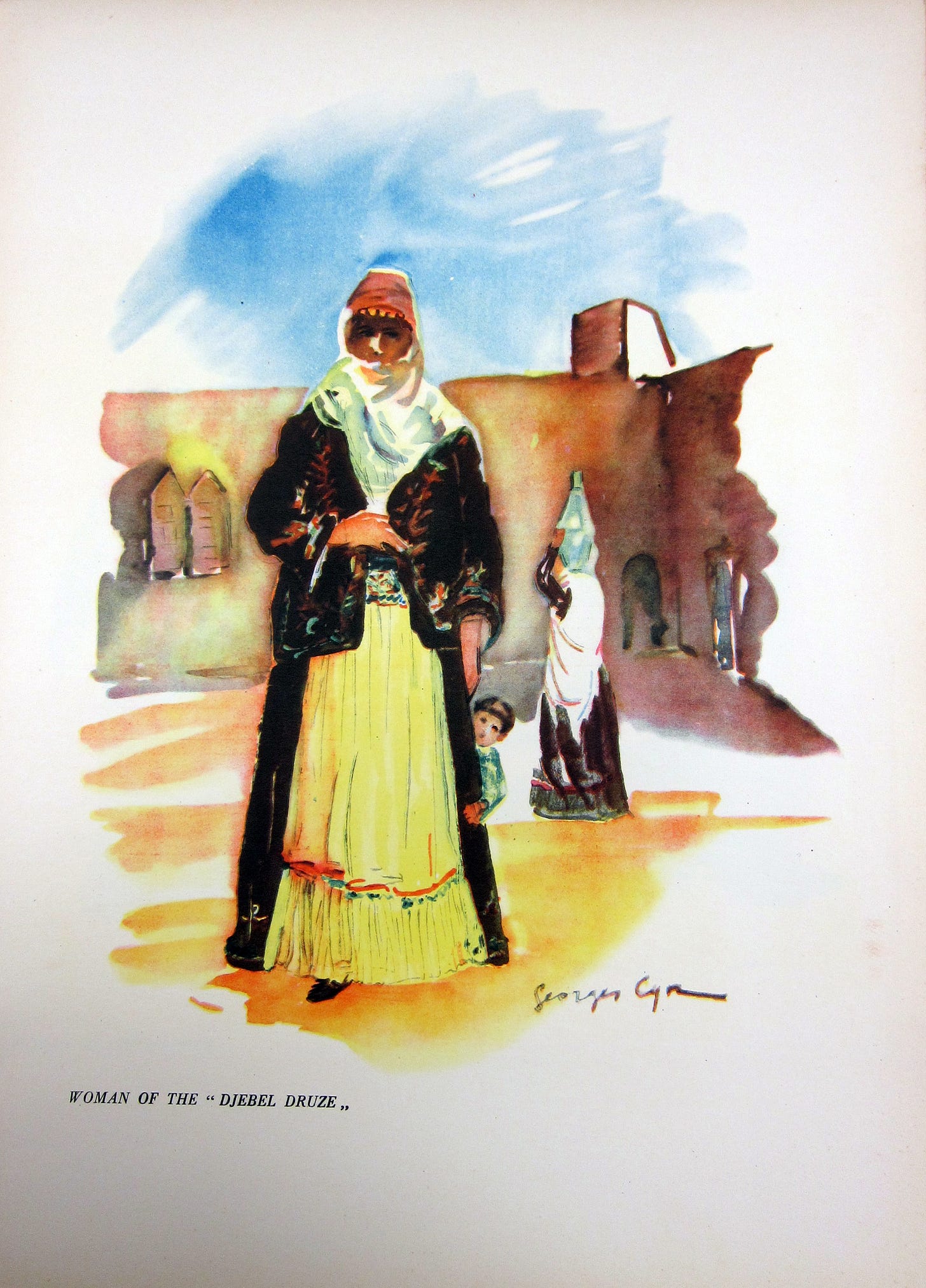

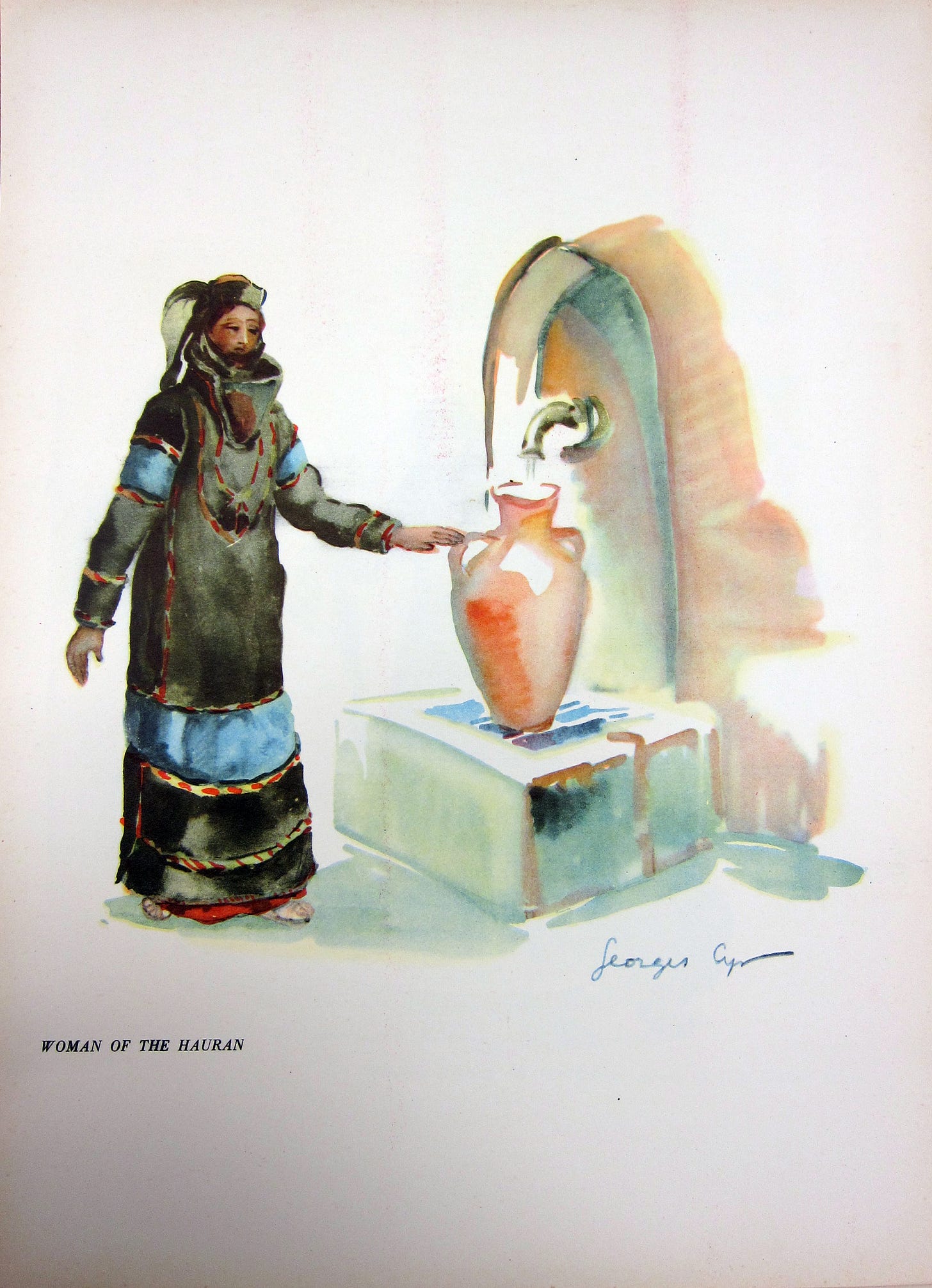

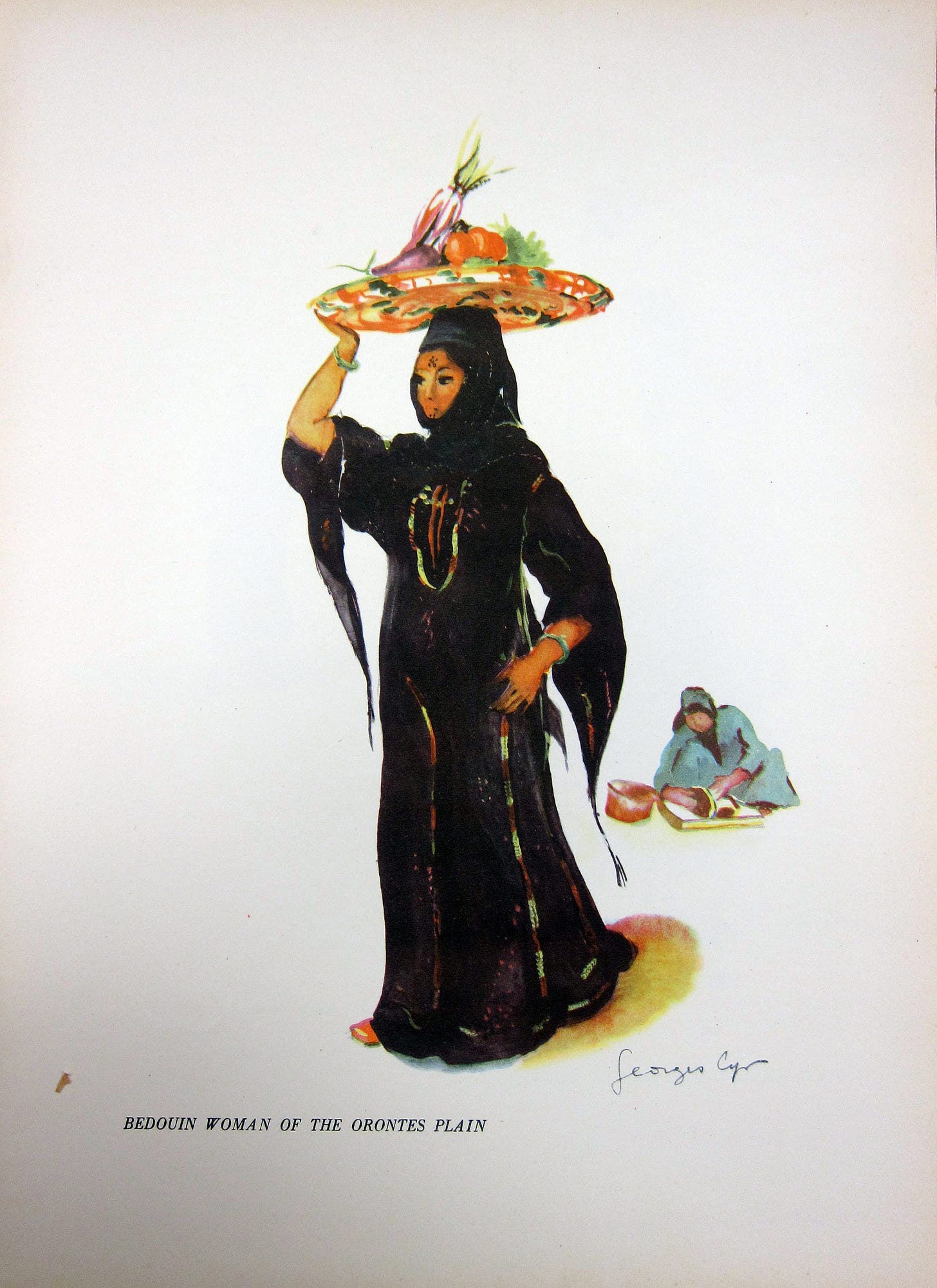

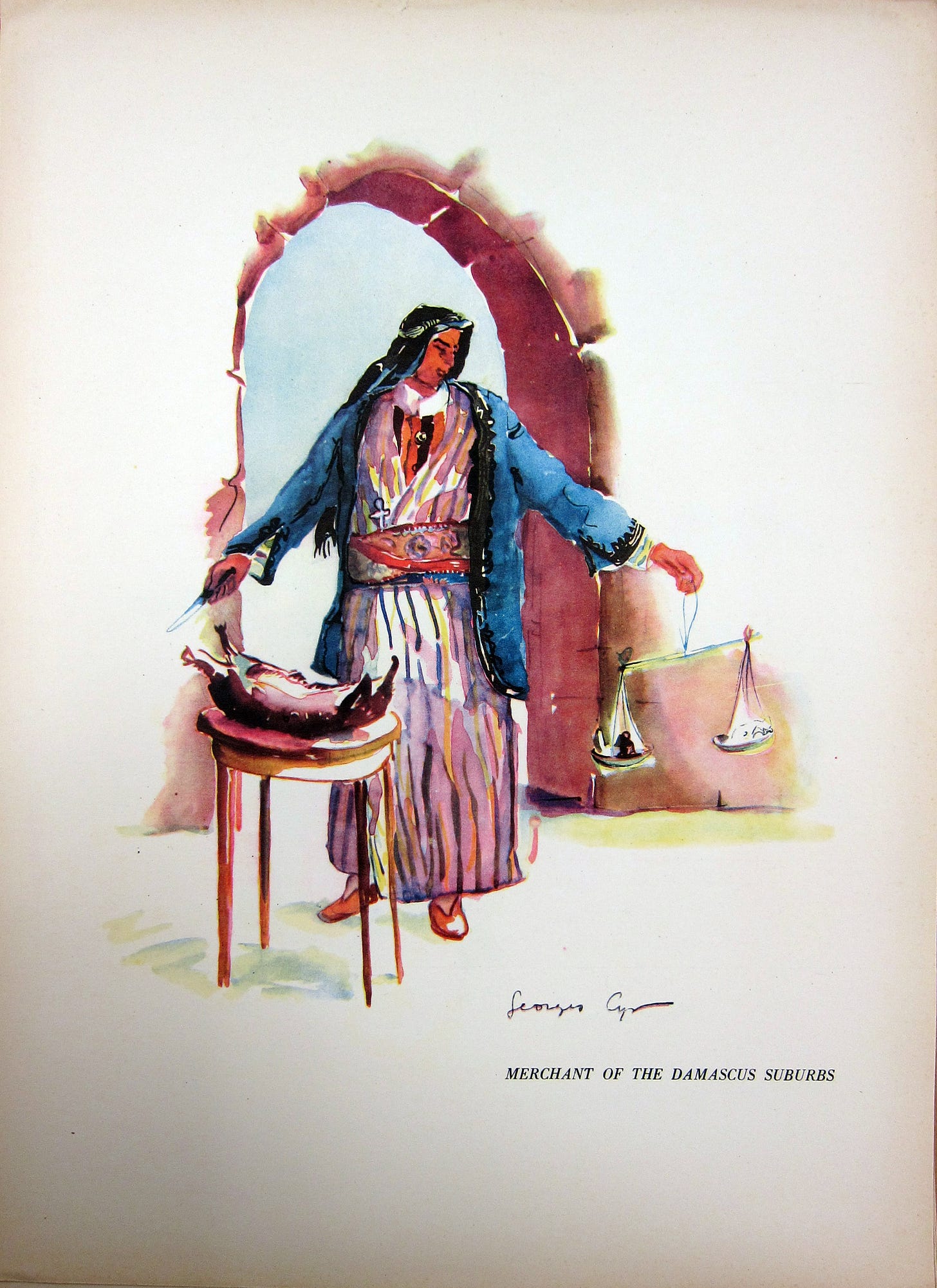

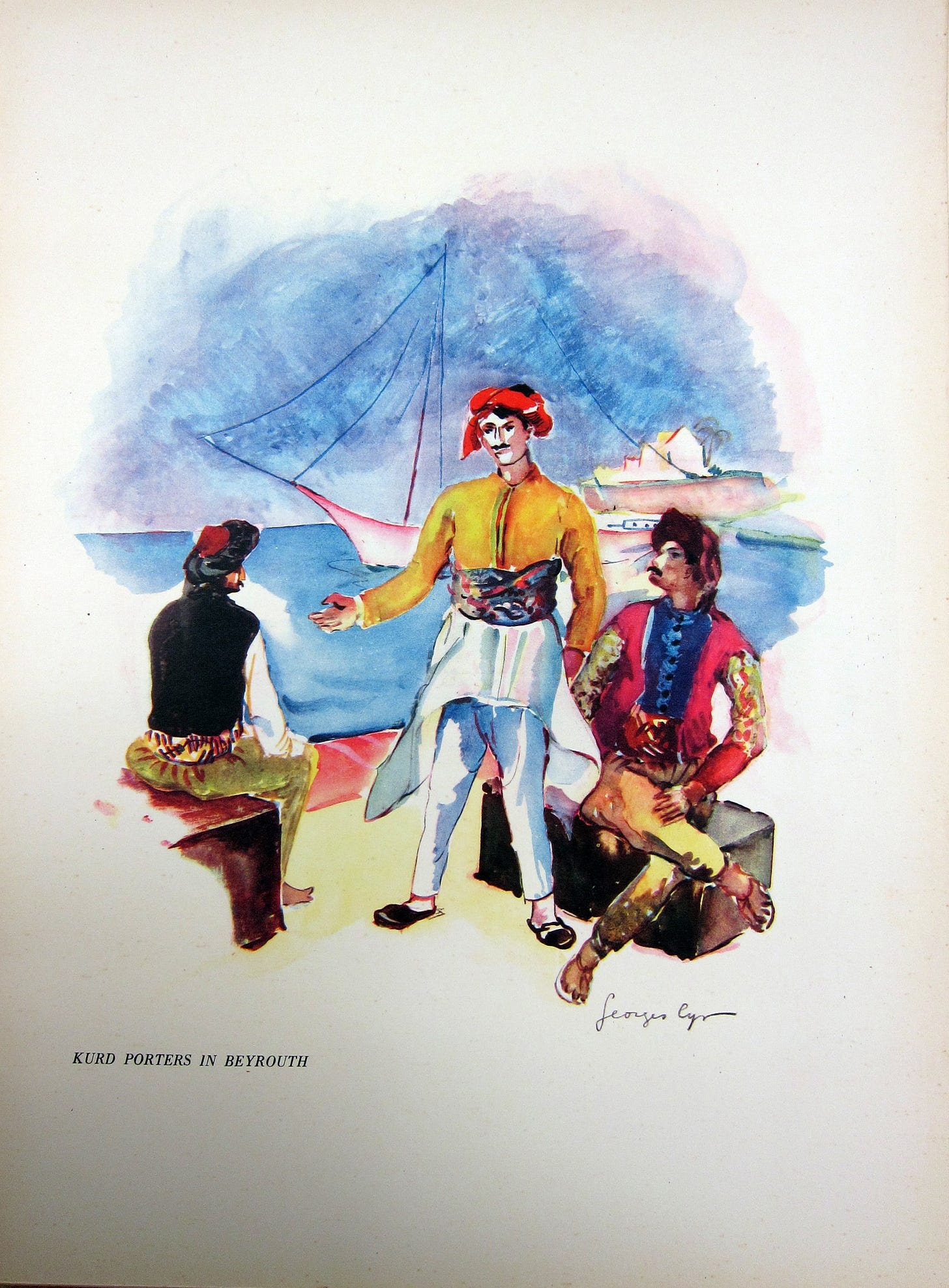

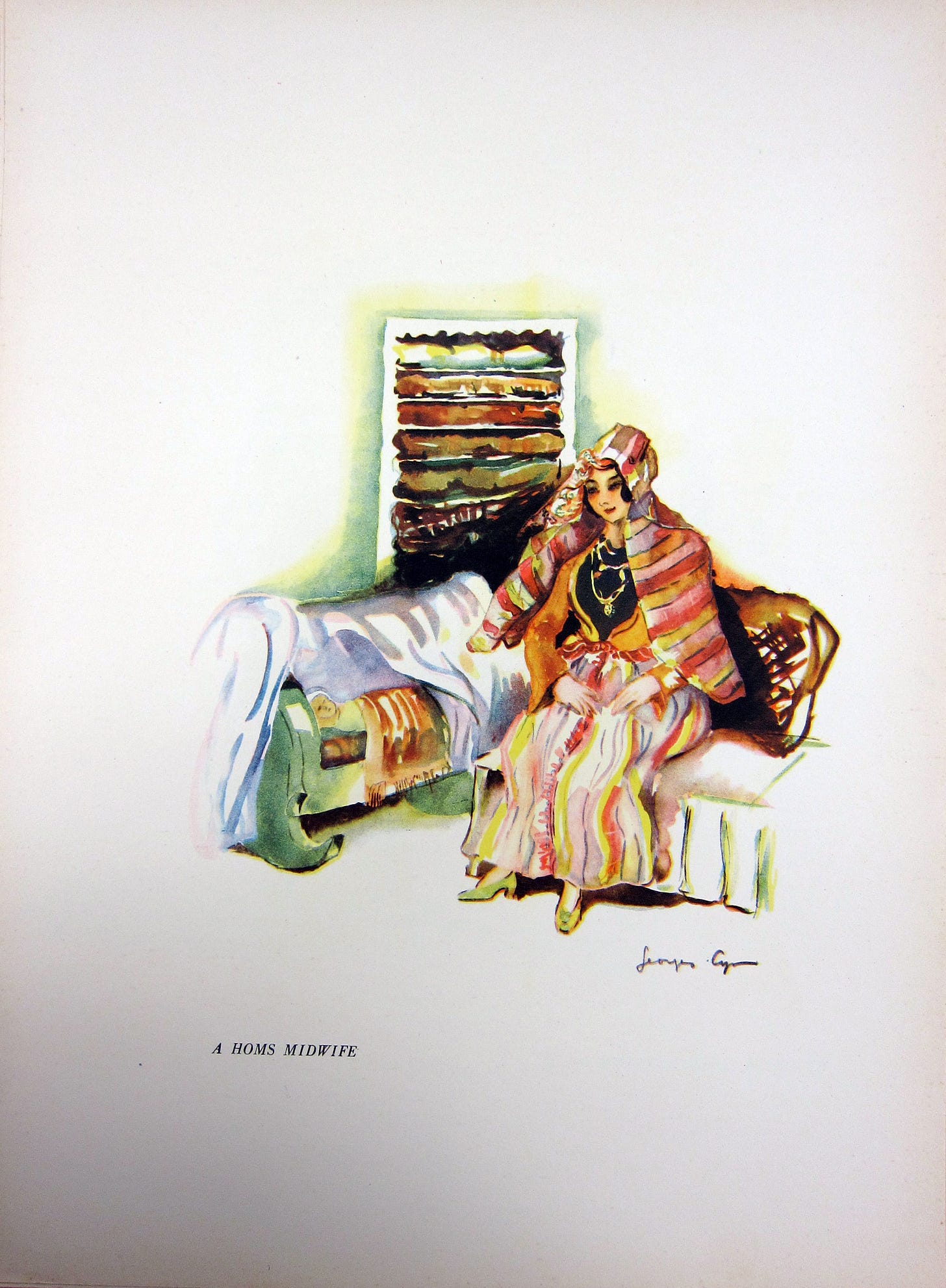

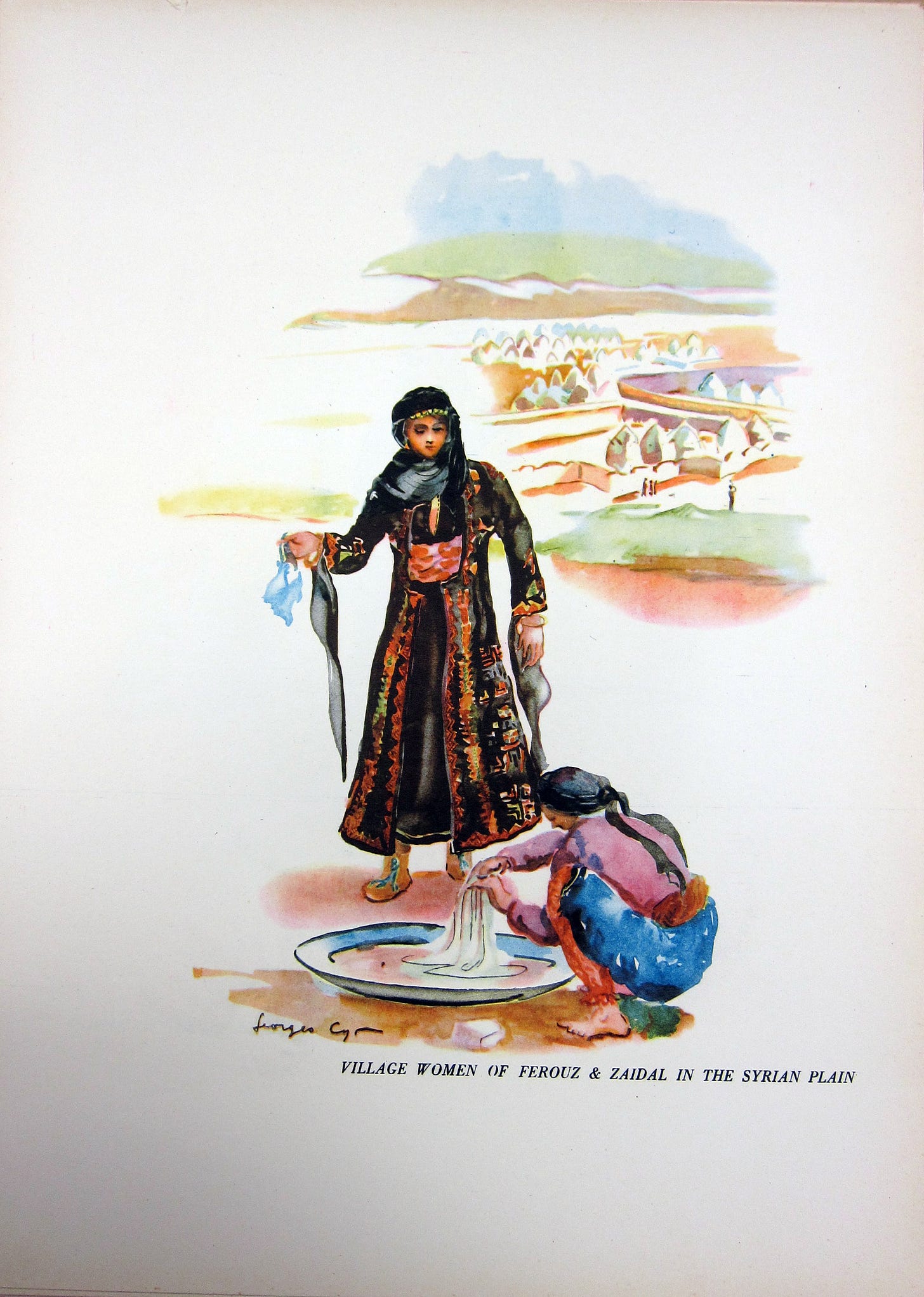

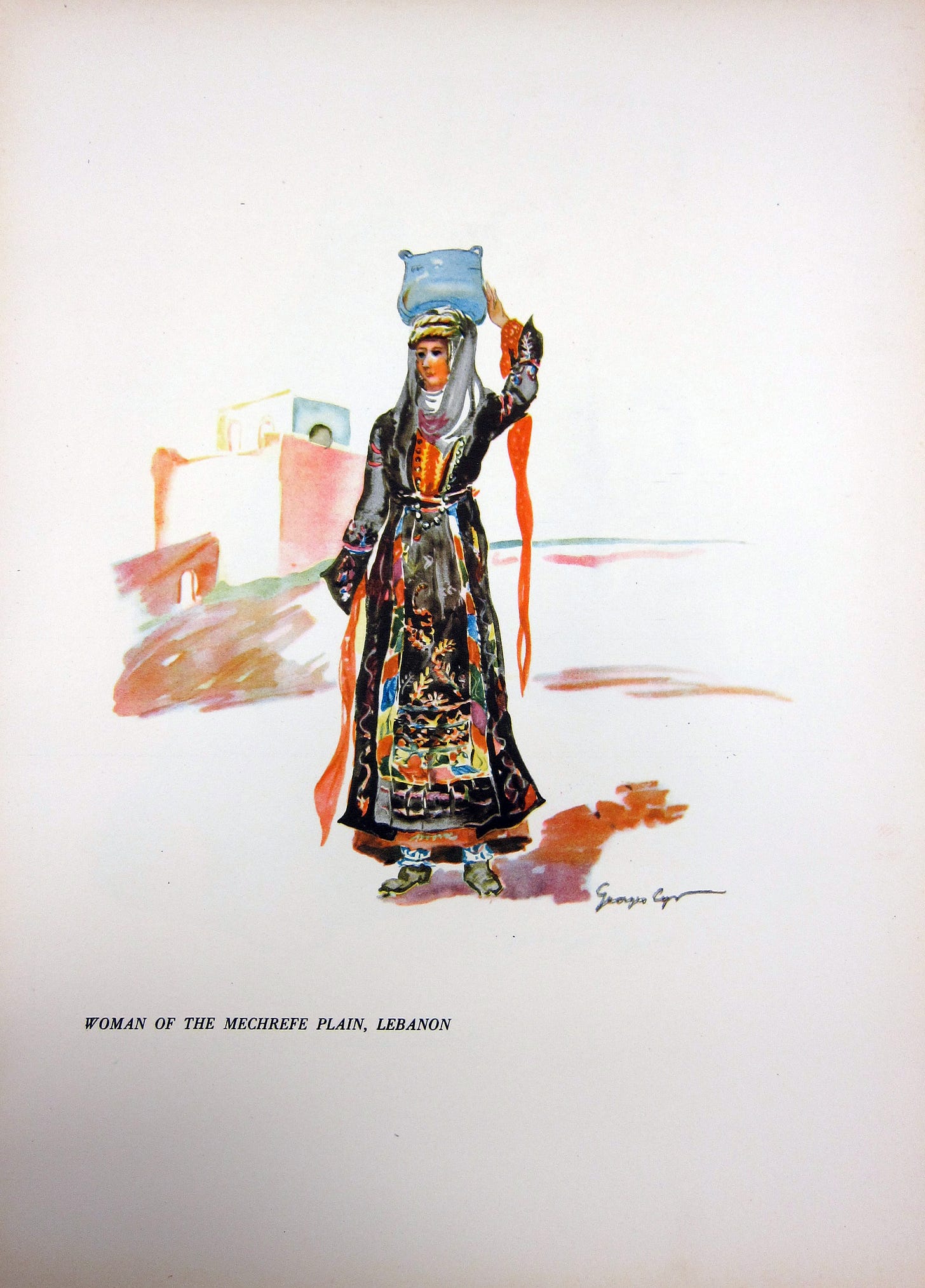

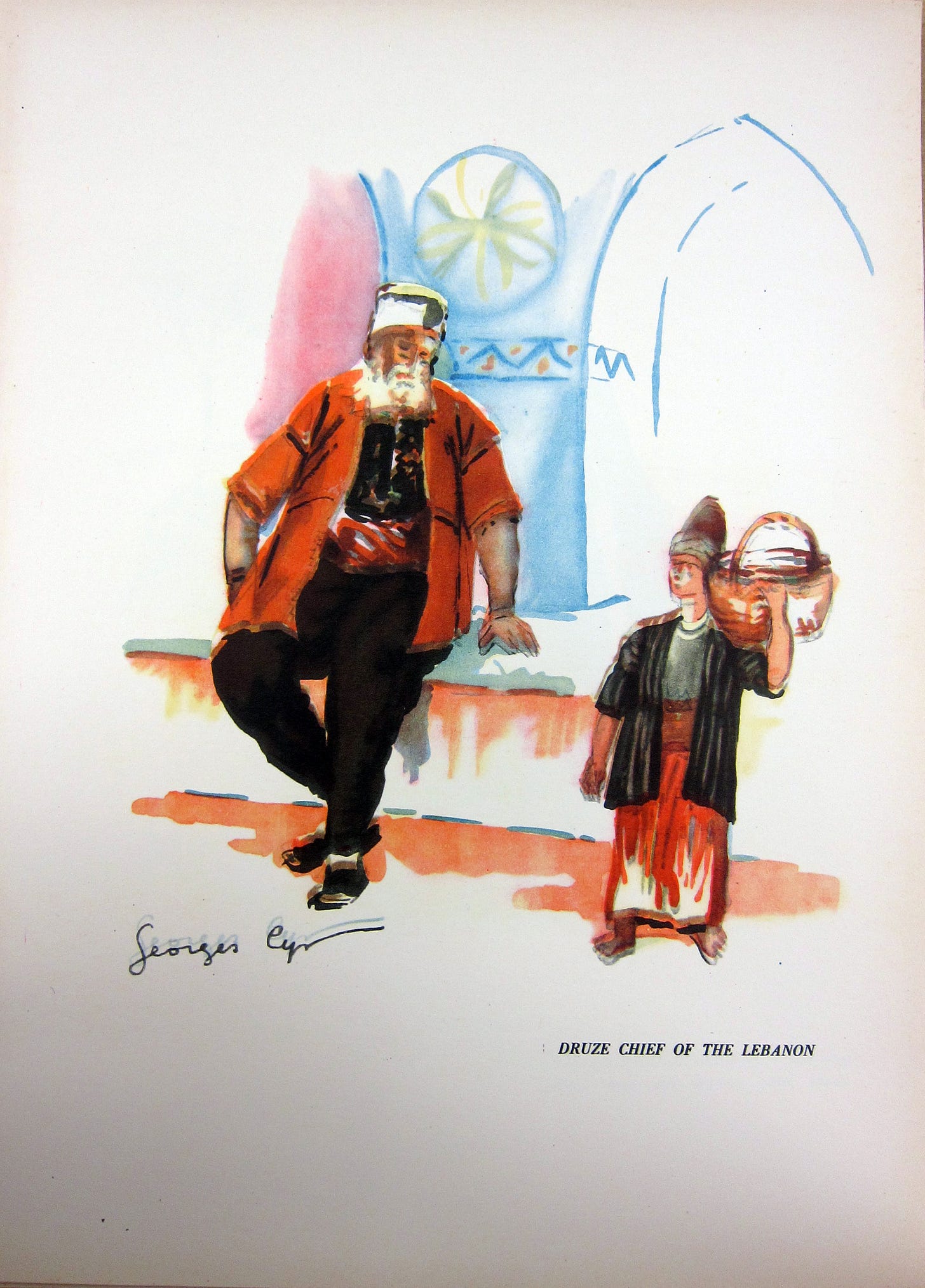

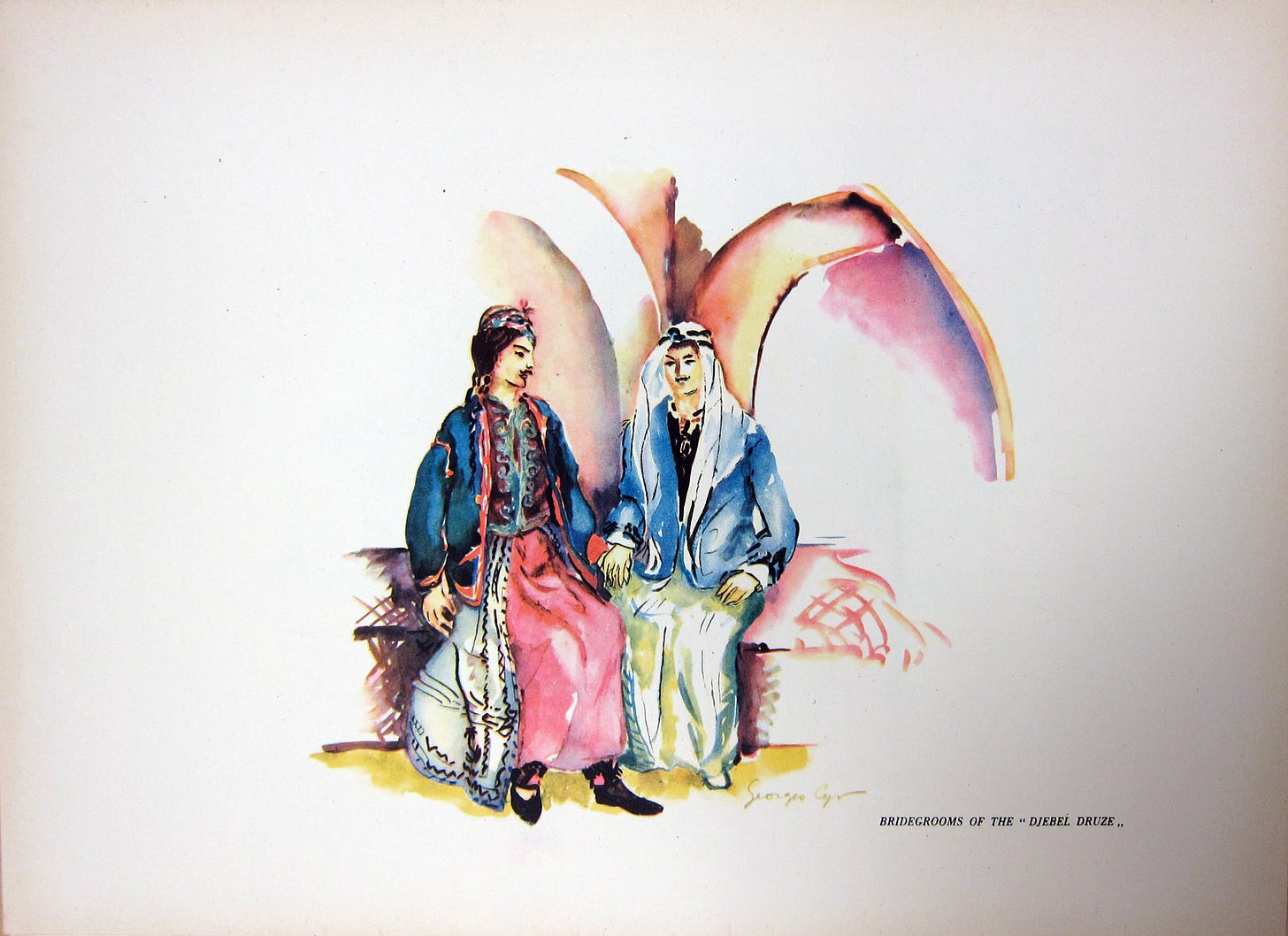

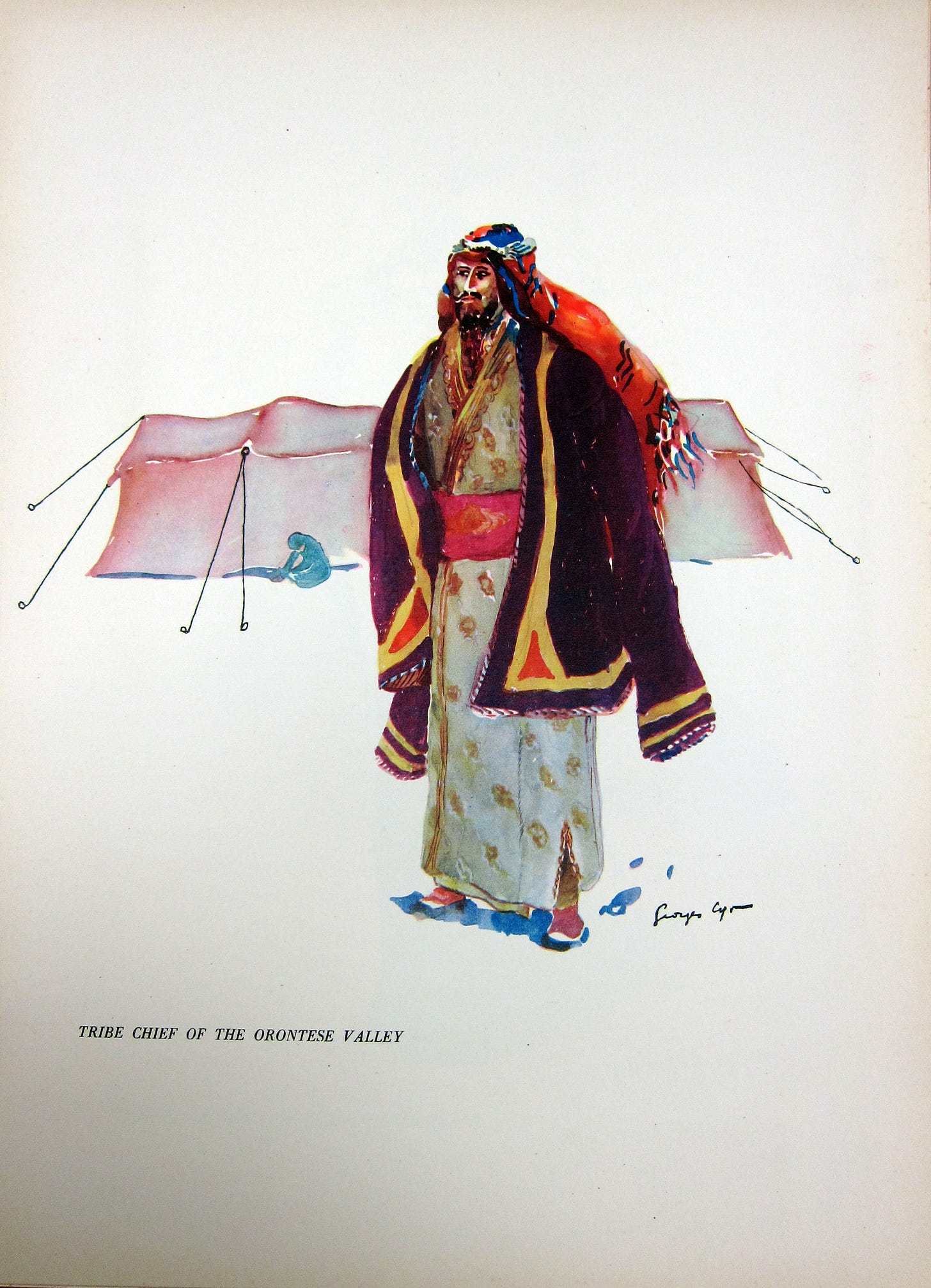

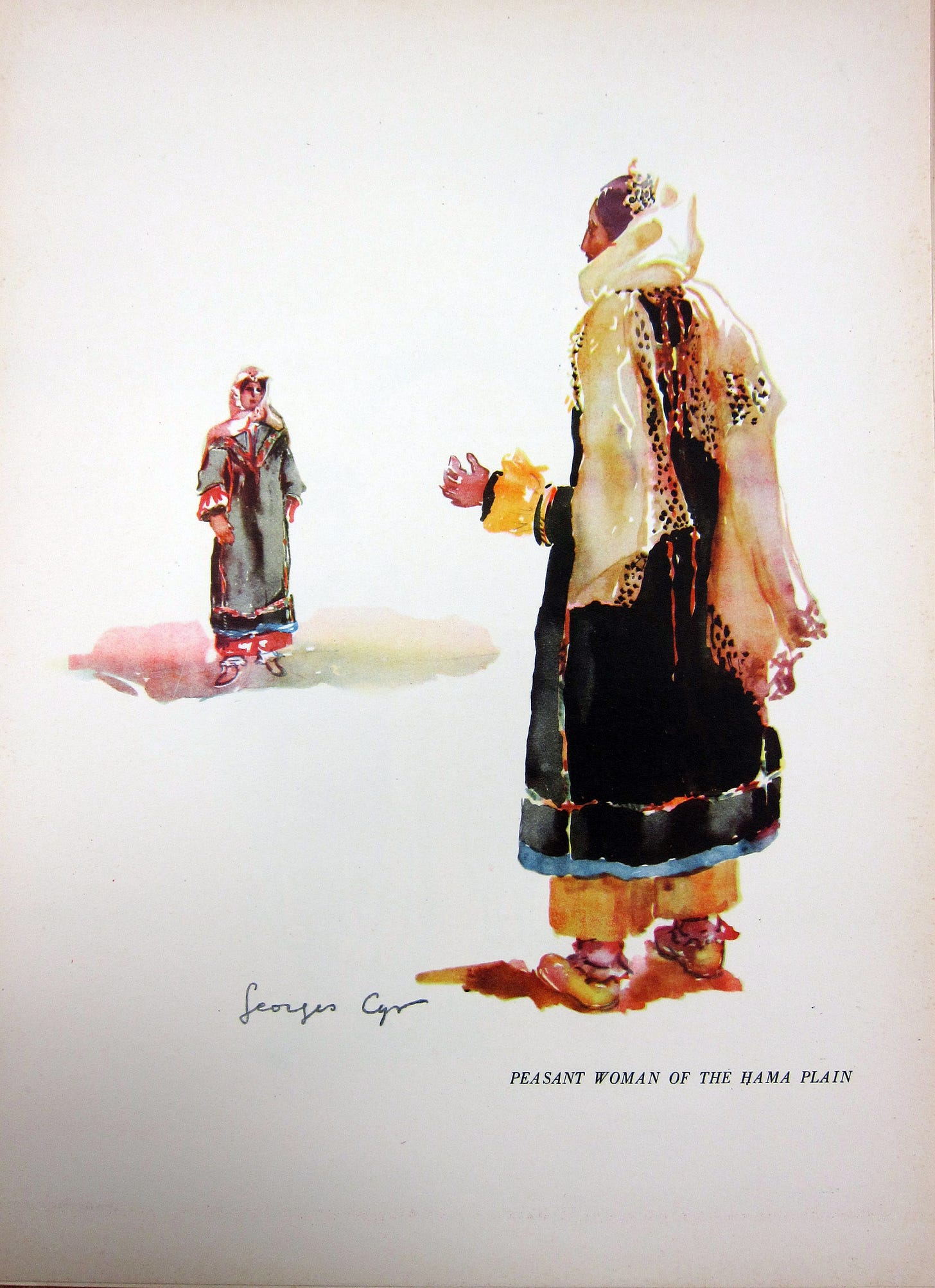

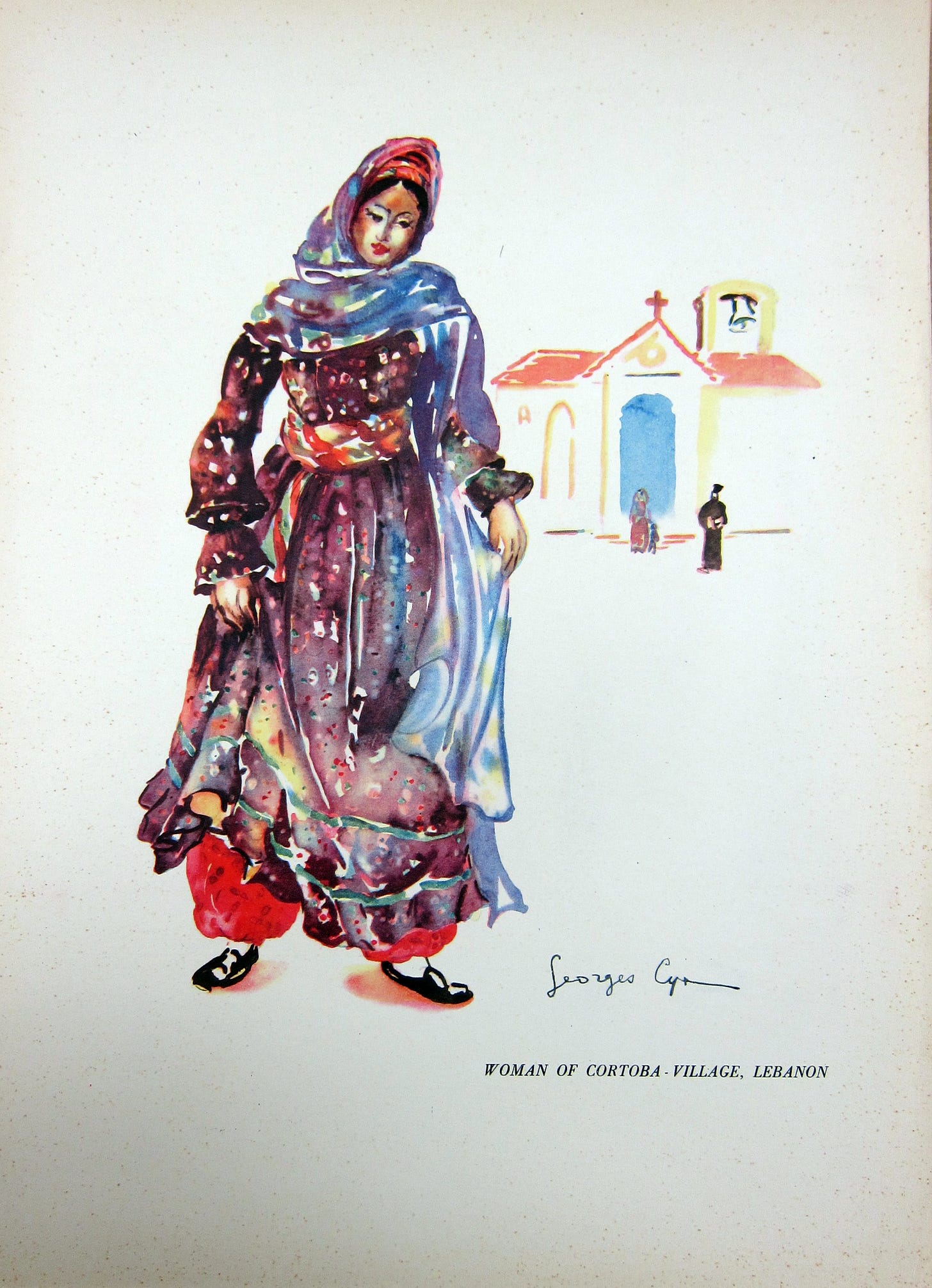

In 1939, Imprimerie Catholique—the Catholic Press of Beirut, which operated from 1848–2000—published a folio of watercolours by the French artist Georges Cyr of Lebanese and Syrian Costumes. With a preface by the famous Lebanese author Evelyne Bustros (one of the few women to play a prominent political role in the struggle for independence against the French), these loose-leaf illustrations capture the traditional costumes from an eclectic range of religions, communities, and geographic areas—each of the twenty-five illustrations are labeled with regional and social identification. Though the watercolours are done in a loose and “light, playful” style, they are an invaluable source of information about garment types and the ways they were layered and worn by different peoples in the region.

I first came across Cyr’s work and this folio through my research on Thea Porter. As many of you might know, I wrote a book and curated a museum exhibition on Porter after having written my master’s thesis on her—she, and her ties to the Middle East, were also an integral part of my (unfinished) PhD dissertation. Thea was born in 1927 in Palestine, then under British mandate, to an Irish Presbyterian minister (of Russian Jewish extraction) and a Tunisian-French mother. Raised in Damascus, Syria, Thea was immersed in the textiles, textures, colours, and cultures of the Middle East from birth. After studying in London, she returned to her family—by then living in Beirut—in the late 1940s, where she met and married a British diplomat.

Prevented from going to art school earlier, Thea chose to devote her early married life to studying painting. In her memoir, she recalled, “Bob and I set up house in Beirut and a year or two later I gave birth to a daughter, Venetia. I was also finally able to start painting and was fortunate enough to have as a teacher an old, highly-skilled French expatriate, Georges Cyr, who excelled in the difficult art of water-colour. Before coming to Beirut, he had lived in Paris were he had been a friend and contemporary of Roger de la Fresnaye and Robert Delaunay, inventor of 'Orphism’, a vibrant outgrowth of Cubism. Georges Cyr lived in a high-ceilinged, red roofed Arab house built in the nineteenth century in the Marseilles style, crossed with Ottoman influences, on the very edge of the Mediterranean. The view of the sea through the coloured panes of his windows figured repeatedly in his own pictures. I used to work with him several mornings a week.”

Georges Cyr was born in Montgeron, France in 1881. According to a biography written by L'or Iman Puymartin, “At the urging of French impressionist painter Armand Guillaumin, he began his artistic career in 1910, exhibiting at the Salon des Independents in 1924… In France, Cyr adhered to the basic aesthetic principles of the Rouen School, a term describing mainly French artists who lived in the city of Rouen during the early 20th century, practicing post- and neo-Impressionist styles.” When his marriage fell apart in 1934, he decided to leave France for a tour of the Middle East. Upon reaching Beirut, he fell madly in love with the city—it became his home until his death in 1964.

Puymartin continues: “Though he produced a rich corpus of oil paintings inspired by the Lebanese landscape, Cyr made his livelihood in Beirut by selling watercolors. His visit to the ‘Paris of the Middle East’ was initially intended to be temporary, but after a few weeks in the city yielded new friends both French and Lebanese, the artist found himself unable to leave. To Cyr, what Lebanon lacked in traditional Western arts institutions was made up for in the richness of culture and the company of the close friends he made—the first being a Lebanese poet by the name of Georges Schehadé. Cyr’s studio became a social and intellectual crossroads for artists and writers, frequented by such esteemed characters as Shafic Abboud, Omar Onsi, Moustafa Farroukh, and Elie Kanaan. Lebanon offered Cyr a sense of warmth, comfort, and hospitality that was completely foreign to him, and preferred its pace of life to the hustle of Paris. It also gave him a sense of importance and relevance, as he was able, to some extent, to teach Lebanese art students the techniques and aesthetics he had learned in his native France. Of course, Onsi, Farroukh, and others had completed their educations in France as well, so much of Cyr’s knowledge was redundant, but he nevertheless encouraged the study and practice of cubism among local artists and made a major impression on the Beiruti art scene.”

Thea studied with him in the 1950s, by which time he was deeply embedded within the local art scene. Around 1960, following a crisis of confidence regarding his place within art history, Cyr abandoned watercolor in favor of oil paint and returned to cubism; “His later cubist paintings draw their color palette from the warm tones of the Mediterranean, and incorporate the hazy, dreamlike handling of paint that distinguished many of the Rouen School painters.” By that time, Thea was having her own gallery shows in Beirut—while well on her way to establishing herself as a painter of great importance there, she abandoned that path when she left her husband in 1964 and moved to London, eventually leading her to become a fashion designer renowned for her designs inspired by the textures, colours, and garments of the Middle East.

In my book on Thea, I included the illustration of the “Bedouin woman of the Orontes”, comparing its sleeves and garment shape to several designs within Porter’s oeuvre: “Described as ‘mediaeval,’ the dangling sleeves of these garments echo the late fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century houppelande (a robe usually featuring long, trailing sleeves),1 as well as the traditional dresses from villages around Damascus2 and nineteenth-century Turkish overdresses.3 Perhaps related, and in a similar vein, Porter’s painting teacher in Beirut, Georges Cyr, illustrated a volume of Lebanese and Syrian traditional costume: among the leaves detailing men's and women’s dress are several kaftans with similar dangling sleeves and embellished plackets.”

Below are all twenty-five watercolours from the folio, photographed by me in 2011 from Special Collections and College Archives (SPARC) at the Fashion Institute of Technology. I have previously written about Thea Porter’s homes and her interest in astrology and divination for this newsletter.

These lines do not constitute a preface. In the domain of costumes they reveal the folklore of the land of gods.

They outline the tracks of a history which aspires to last.

They affirm the ancient influence of the sumptuous rustic garb,

Of the long plaited hair of Djebelilads, and of the tall sugar-loaf felt hots of our peasants.

A heritage from Cana, Palmyra, Galilee, and the Phoenician cities which catered to monarchs.

These pictures sing the quaint charm of Lebanese seasons.

The fragrant stillness of noon:

The summer days in the shade of fig and olive-trees.

The deep-toned key-board of the hills when the chimes from belfries echo across the valleys.

And when the twilight shivers in its retreat.

These pictures are the nostalgic ATABA (folksongs) which lulled our childhood at eventide.

The humble palette of our vivid autumns.

All the purple of Tyre and its rich glow on our coloured skies, and on your inimitable gait,

Oh ! women of my country, when at sunset your garments stand out in the light of October and its breeze as you tread along the lane leading to the fountain.

They are the strange perfume which you exhale into the cool evening air, beloved Lebanese soil.

Oh ! my mother and my last pillow !

These lines do not constitute a preface ;

I am but a scribe inspired by the god of reminiscence.

(Translated from the original of EVELYNE BUSTROS)

Aileen Ribeiro, Dress and Morality (Oxford 2004), p.49.

Hana Chidiac, wall text in the exhibition L’Orient des Femmes vu par Christian Lacroix, Musée du Quai Branly, 2011.

Thea Porter, undated and unlabelled note (V&A archive). A similarly paneled gown with scalloped edges from Entari in Turkey dates from c.1900 (fig. 19, Victoria & Albert T.96-1954).