On July 2nd, Hyperallergic reported:

The Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), the only four-year school devoted to contemporary Indigenous arts, could lose all of its federal funding beginning October 1 if President Trump’s proposed federal budget is passed.

Trump’s Fiscal Year 2026 budget proposal suggests completely eliminating funding for the IAIA, which received approximately $13 million in the prior two fiscal years. The institution relies on federal funding for 75% of its operating expenses, IAIA President Robert Martin, a member of the Cherokee Nation, said in a statement shared with Hyperallergic. Without federal dollars, he said, student mental health services, housing, scholarship programs, and the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts would cease operations.

Martin said the institution’s 850 enrolled students predominantly come from rural reservations. A spokesperson for IAIA told Hyperallergic that 92 federally recognized tribes are represented in the student body.

“In one budget, nearly 63 years of progress in Indigenous higher education and artistic expression is at risk,” Martin said. “We are the only institution of our kind in the world, and our mission is more vital than ever.”

The article continues, “IAIA, which describes itself as the ‘birthplace of contemporary Indigenous art,’ opened in 1962 as a high school on the Santa Fe Indian School campus, one of the two federal boarding schools established in New Mexico during the late 19th century with the aim of forcibly assimilating Native children.” Eight years after the IAIA opened, it was profiled by Blair Sabol in the third issue of Rags (August 1970), the counterculture fashion magazine that has been central to much of my academic work. With these possible cuts to its funding, I thought I would share her article to highlight just how important the school was then and how important it continues to be today.

Sabol captures the IAIA and its young artists fresh in healing from the trauma of forced assimilation, haltingly relearning their cultural artistic traditions in a world more intent on stealing them than celebrating. She discusses the popularity of Native American motifs and design elements in dress, whether a print for a Seventh Avenue gown or a fringed buckskin vest worn by a hippie—what Dakota historian Philip Deloria calls “playing Indian”:

Sixties rebellion rested, in large part, on a politics of symbol, pastiche, and performance. Influenced by media saturation and the co-optative codes of fashion, the emblems of social protest were plucked from different worlds and reassembled in a gumbo of new political meaning. That headband might mean Geronimo, but it also meant Che Guevara and Stokely Carmichael. Indeed, it meant many things, depending on its context and its interpreters. Sacred pipes, Black Power fists, Aztlan eagles, peace signs, Hell's Angels, beers and joints, Peter Max design— everything fed into a whole that signified a hopeful, naive rebellion that often had as much to do with individual expression and fashion as it did with social change.1

Into this world, where their deeply personal cultural adornments had been co-opted for fashion (whether fashionable protest or fashionable ladies who lunch), came the artists of the IAIA.

BRIDGE OVER TROUBLED WATERS: Story of the Institute of American Indian Arts

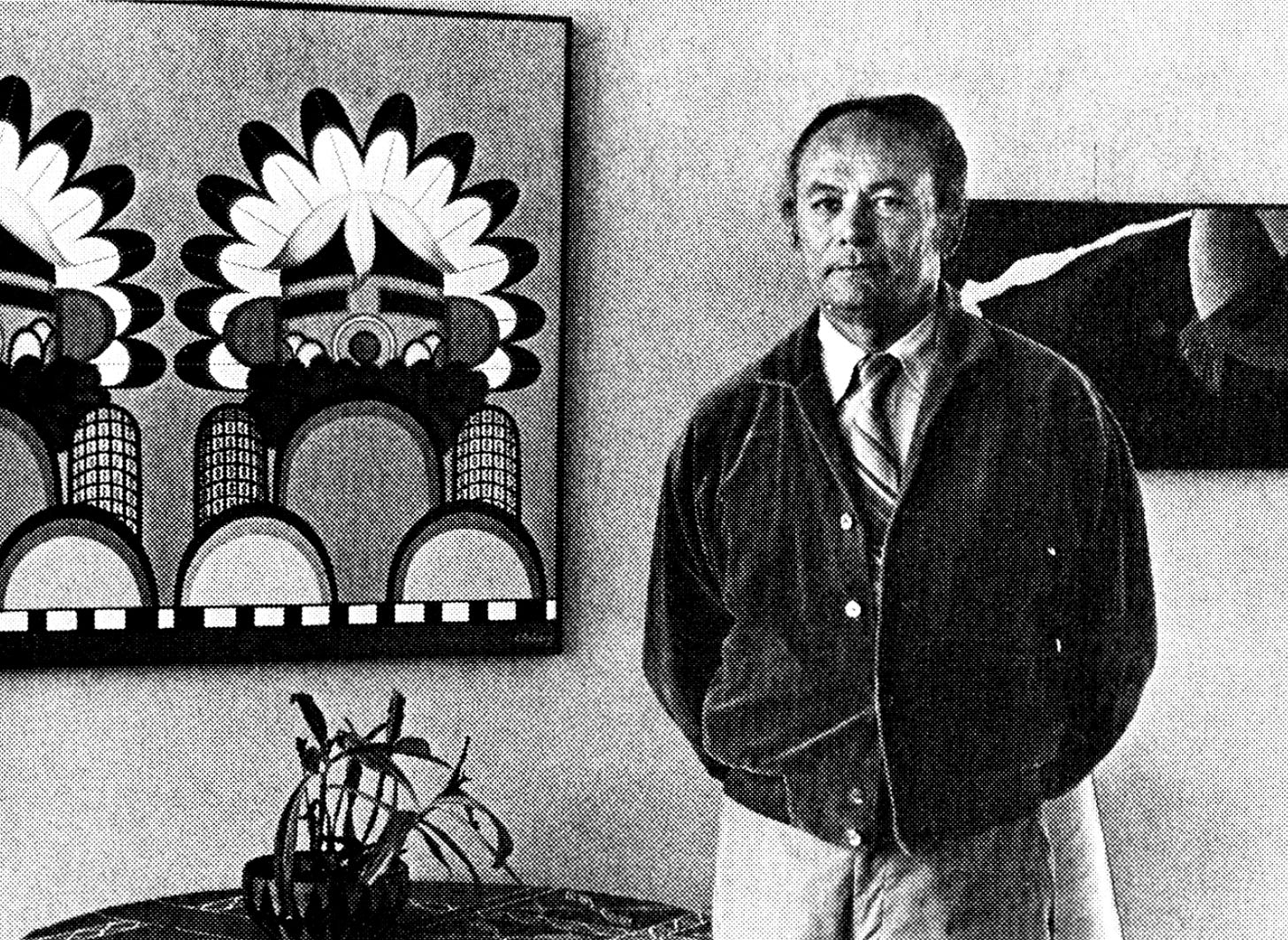

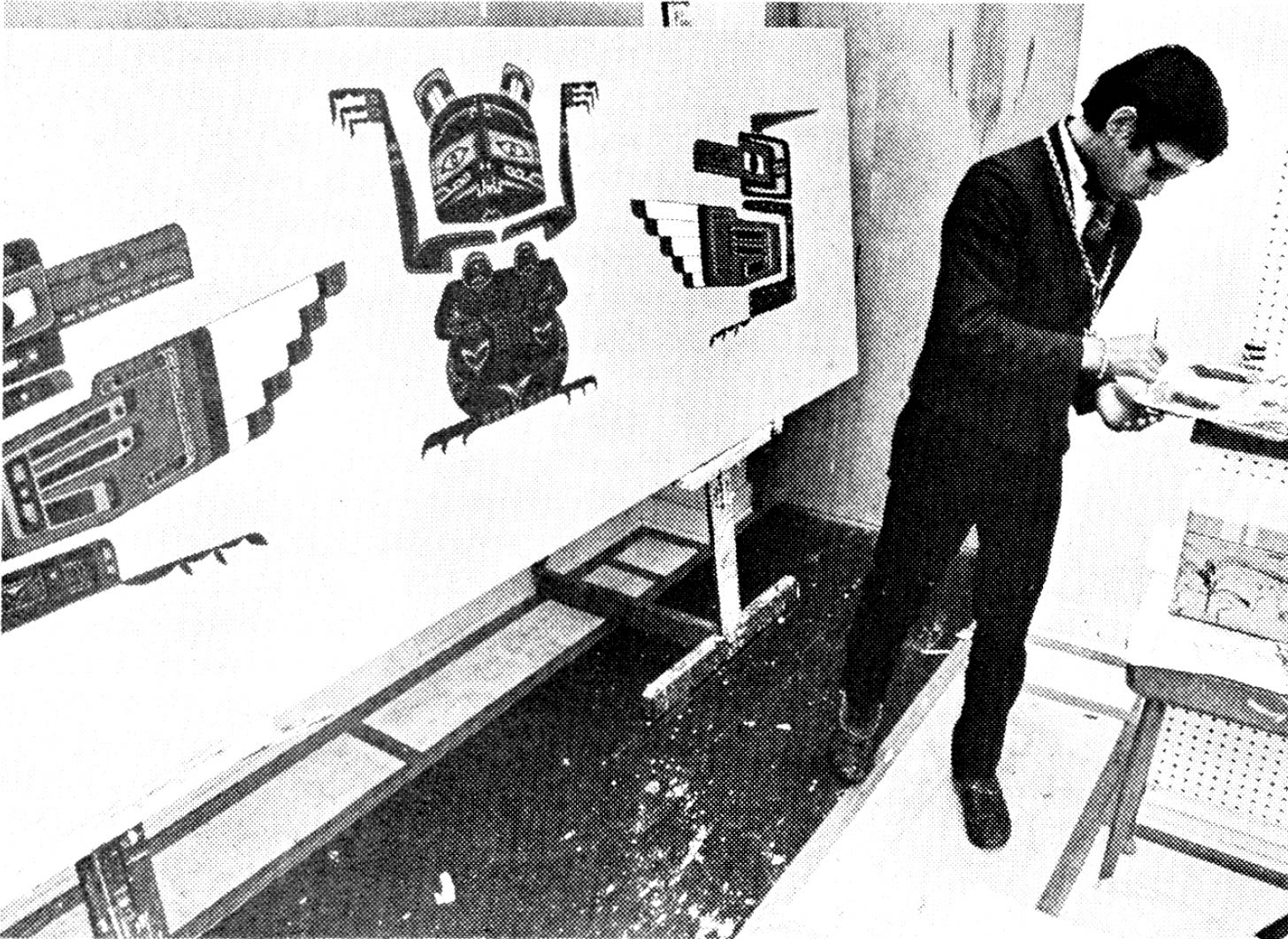

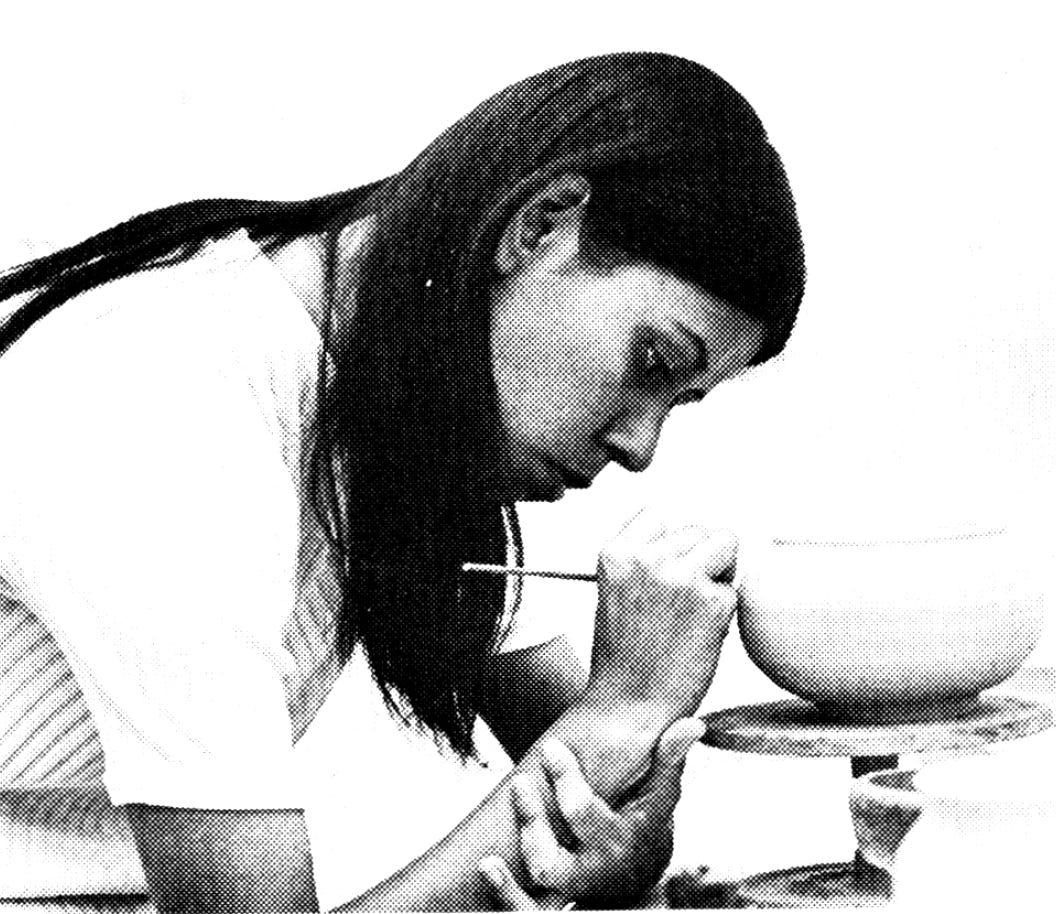

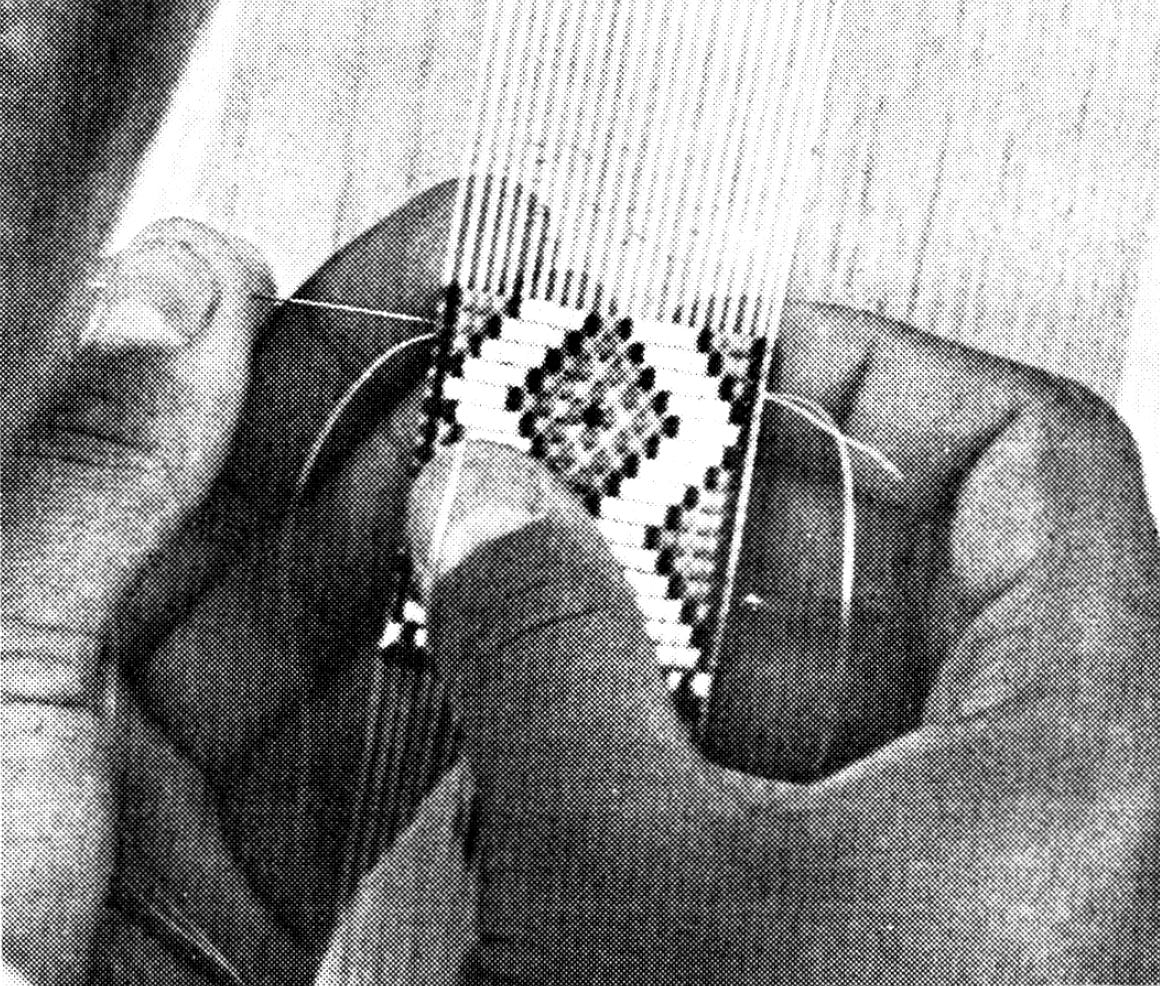

Rags, August 1970. All text by Blair Sabol with photos by Karl Kernberger

"It will not be the intent of the Institute of American Indian Arts to 'ram anyone's culture down his own throat.' But it will be the intent of the Institute to make special deference to the fact that the (Indian) students are of a different cultural group and, in being so, have unique and valuable contributions to make, thereby making great use of traditions as springboards for personal creative action. The institute will assume from the beginning that it is not the business of an artist to attempt to recreate a tradition. Rather he is constantly in the process of creating a new one." - Lloyd New, Director, The Institute of American Indian Arts

What's been going down in American Indian education today is a study in cultural confusion. Over the years the Bureau of Indian Affairs—B.I.A. (nicknamed by most Indians the Bureau of Incomplete Action or Mother Superior)—has been shipping Indian children miles away from their own reservations to government controlled and run boarding schools. And for six years (or however long the Indian kids can stand it) they are given a crash course in Anglo-American assimilation or homogenization. It's no wonder young Indians today are going through identity crises. Though the Red Power movement is officially on the warpath, the new young Red leaders are few and far between. Education has a lot to do with that lack.

Obviously leadership stems from individuals who have faith and confidence in themselves. The B.I.A. educational system gives the American Indian youth nothing of that. In B.I.A. schools he is taught little of the magnificence of his tradition.

"The Institute of American Indian Arts, by emphasizing the best that is inherent in many Indian art traditions, leads to a new pride for Indian people." —Lloyd New

In 1962 The Institute of American Indian Arts opened in Santa Fe, New Mexico with a student body of 140 Indian boys and girls ranging in age from 14 to 22. The purpose and plan was clear: to offer the artistically inclined Indian youth a broad aesthetic curriculum (along with the straight academic program), and in so doing make him aware of himself as an individual with a meaningful contribution to make to his contemporary world, and aware that he is part of a tremendously rich aesthetic tradition.

"When an Indian student weaves a fabric, it is more motivating than memorizing White man's history."

So far the Institute has given soul injections to many Indian kids who had been numbed by their earlier academic experiences of learning in the "good solid American way." At the Institute, when an Indian student weaves a fabric, welds a ring together or molds a pot, he is experiencing something more potently motivating than memorizing Custer's Last Stand from the white man's viewpoint.

Even though the Institute is B.I.A. controlled it is headed by Lloyd New, a Cherokee. His staff is a competent cross section of craft, art and academic people. However, only a quarter of them are Indians. All the arts are offered-music, dance, creative writing, drama, photography, sculpture, painting, ceramics, jewelry, weaving, textiles and graphics. This kind of program is available to Indians nowhere else. Even multi-media light show techniques are taught by an ex-San Francisco light performer, Jack Frost. Not to mention film making—the students have just finished their own "Red Reflections of Life," a twenty-six minute flick for educational distribution. Today there are 88 tribes represented in the Institute's student body. 88 tribes. 88 different life styles. But 400 individually unique people. And all are encouraged to be just that.

"What's been going down in American Indian education today is a study in cultural confusion."

Physically The Institute of American Indian Arts has the fresh modern appeal of an upper middle class suburban high school... with adobe overtones. There are very few campus disorders and as one teacher remarked,

"A few fist fights in the dorms and maybe a few personal drinking problems, but no race riot hassles." Indian kids are not competitive aggressors by nature. At least the Pueblo Indians aren't. However there are hints and subtle hits that are periodically thrown at a few of the government school's Anglo employees. A hallway bulletin board composed by students out of recent newspaper headlines (or lines from their own heads) concerning Red Power: "Uncle Tom-A-Hawk wants you to work for the B.I.A." and "Get ahead with Red."

As great as its goals are, there are problems at the Institute. For instance, there is a need for more fashion instruction in the curriculum. The Indian kids are aware of the mass ripoffs of their fringe, beaded headbands and buckskin moccasins by most of the country's hipsters. They do, indeed, dig the feedback but would rather see that designing done by the Indians themselves and not by some little old Geronimos on Seventh Avenue's Seventh Mesa. A visit to the Institute's Hookstone Art Gallery (located on campus and run by the students) will back up this fact. On sale are their out-of-sight artifacts, silver jewelry, pottery, posters and incredible woven fabric. But nothing in clothing.

One of the boys in textile class was tie-dyeing his own shirt and was excited yet confused about the learning method. He was doing it totally on his own but craved advice from a tie-dye diehard on the actual techniques so that he could make up his own patterns for some clothing ideas that were brewing in his head

It's amazing to consider that many fabric designers such as Jack Larsen and Julian Tomchin have based whole collections on Indian and Aztec patterns. And yet Julian Tomchin admitted to never having gone to the Indians in person for some on-the-spot-research. He said he got his ideas from library books. It would be a good thing if he did make a visit to the first and second mesa, and maybe on his way give a guest lecture at the Institute's textile class. Other fabric designers might do the same for that matter. F.I.T. and Pratt aren't the only design institutes in existence.

The Institute also suffers from a Generation Gulch (not a gap). Parents are concerned over the fact that their kids are not graduating into heavy job holdings. But in 1968, 44% did go on to vocational training and 39% entered colleges. Still, to the more conservative and reserved reservation parents, artistic drives and jobs aren't what the Indian nations need today. To them, doctors and lawyers are the starholders for the future.

"Conservative Indian parents think doctors and lawyers are needed more than artists."

Maybe they are right. But then the Institute automatically attracts more artistic (as opposed to academic) people. Anyhow, most of the Institute's graduates eventually return to their reservations to teach arts and crafts.

It's no secret that the old Indian craft scene is dying out as the old Indian craftsmen themselves die. That's why Navajo rugs are top dollar and why the silver and turquoise jewelry (particularly old pawn pieces) keep creeping up into higher price ranges.

But all the Institute's problems are simply ones of cultural turmoil. The fact that the Institute exists and is letting Indians learn and express themselves is what's important. Certainly it's good for the sour image of the B.I.A. The Institute of American Arts may be one of the few golden bridges over the Indian's troubled waters.

SCHOOL FACTS

The Institute is a national school for Indians, offering an accredited high school program leading to a diploma, with arts electives. It has a two year, post-high school vocational arts program as preparation for college, technical schools or employment in the arts. Room, board, tuition and all art materials are furnished without cost to the students.

ELIGIBILITY

1) Applicants must be certified one-quarter or more of Indian, Eskimo or Alient ancestry and live on or near an Indian reservation.

2) Applicants not accepted below grade 9 (14 years) .

3) Post-high applicants can't be over the age of 22.

4) Must be of sound mind and body.

For more info, write (better still, hop in your VW bus and visit) the Institute of American Indian Arts, Cerrillos Road, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501.0

Outside Fashion

When we think of the late sixties counterculture, all of us conjure up in our minds images of their fashion looks. Dress was such an essential part of countercultural identity, regardless if one was a hippie, a Hells Angel, a Black Panther, or a feminist. The mass media, then and now, reinforced how each of these groups was supposed to dress. The ideolo…

"When you dress up you feel good": Counterculture Fashion & Rags

As I was putting together my talk on the counterculture fashion magazine Rags for a symposium tomorrow (in conjunction with the book launch of the new academic volume, Fashion in American Life), I reread the publisher’s letter in the first issue and felt it was rather prescient.

Deloria, Philip. “Counterculture Indians and the New Age.” In Imagine Nation: The American Counterculture of the 1960s & 1970s, edited by Peter Braunstein and Michael William Doyle. New York: Routledge, 2002.