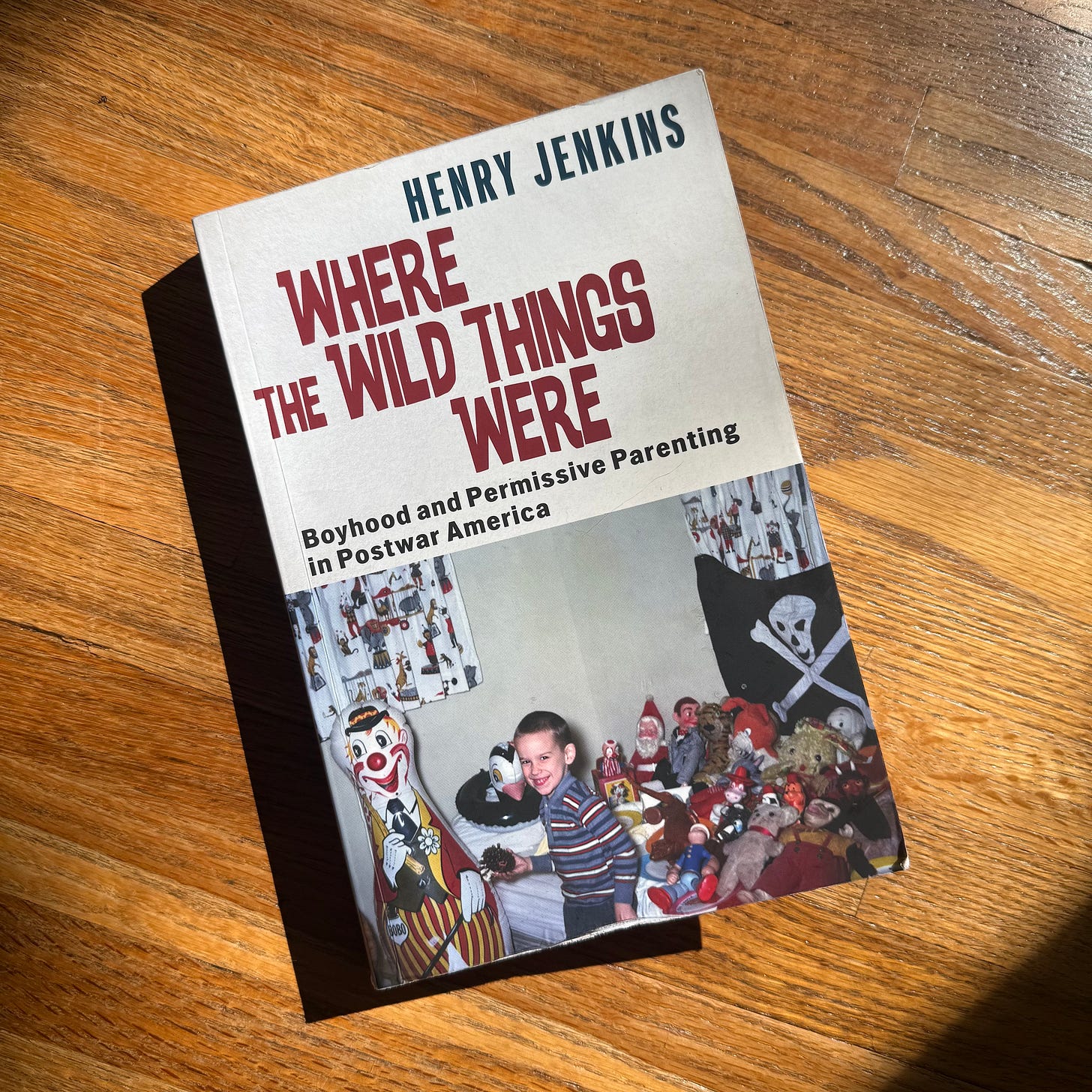

Where the Wild Things Were: Boyhood and Permissive Parenting in Postwar America

A Conversation with Henry Jenkins on his Latest Book

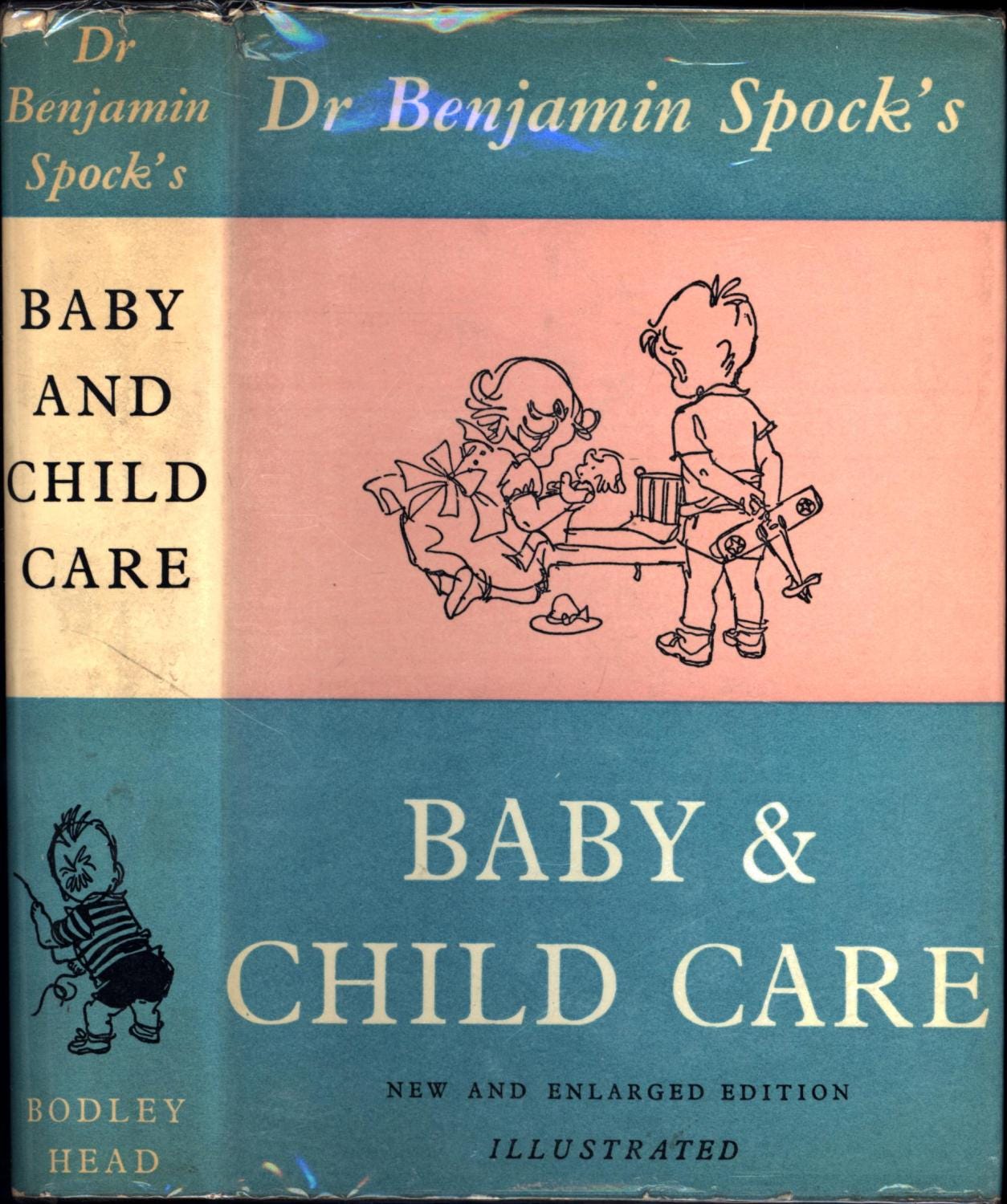

Since having my child last year, I’ve become interested in the history of parenting and of parenting advice. With social media being such a mess of contradictory parenting advice, it often seems impossible to know the right approach. I turned it all off and started to focus on the broader context of how we got to where we are, looking at the differing ways children have been viewed in American society (The End of American Childhood by Paula S. Fass is good for that) and the sharp swings of the pendulum regarding parenting advice over the twentieth century (Raising Baby by the Book and Raising America both cover the history of parenting advice literature). Into this mix steps media scholar Henry Jenkins, whose latest book, Where the Wild Things Were: Boyhood and Permissive Parenting in Postwar America, looks at the complex interplay between child-rearing experts and children’s media in the postwar era. Jenkins articulates how children’s media (books, comics, cartoons, TV shows, and movies) demonstrated and reinforced the ideas of permissive parenting that were being pushed, on a mass scale, by Dr. Benjamin Spock’s Baby and Child Care (the second best-selling nonfiction book of all time in America after The Bible).

Jenkins begins with an overview of the early twentieth-century progressive ideas that paved the way for mid-century permissiveness, focusing on the Child Study Movement and proponents of democratic family life, such as Dorothy Baruch and Dorothy Canfield Fisher. For educators like Baruch and Fisher, “children had core rights that needed to be respected. The hope was that the next generation would be more comfortable with their bodies and their identities, more democratic in their impulses, more exploratory in their learning, and more connected with the world around them than the previous generation saw itself to be.” In 1965, child psychologist Haim G. Ginott explained permissiveness as “an attitude of accepting the childishness of children. It means accepting that 'boys will be boys, that a clean shirt on a normal child will not stay clean for long, that running rather than walking is the child's normal means of locomotion, that a tree is for climbing and a mirror is for making faces." According to Jenkins, the ideal child of the permissive era was a boy (hence this book’s emphasis on boyhood): “almost always white, suburban, straight, middle-class, Christian (mostly Protestant), and above all, American… These boys are curious, adventuresome, messy, noisy, rough-and-tumble, muddy even. They explore the world, questioning everyone and everything. They sometimes disobeyed and often escaped adult supervision; they were natural leaders and embraced a democratic style of living.”

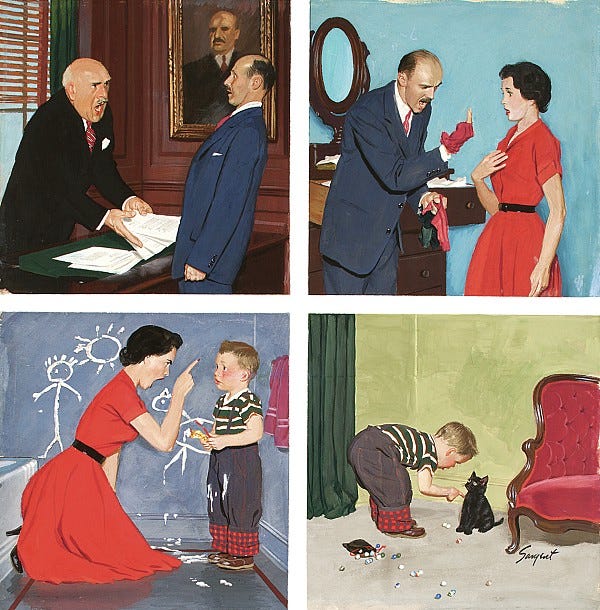

The bulk of Where the Wild Things Were uses children’s media examples to explore their parallels in advice literature and to discuss the very clear messages and lessons about behaviors being broadcast to both children and their parents. As he explains in the text, children learned how to act within this new permissive paradigm by observing how kids behaved in cartoons and comic books, while parents simultaneously learned how to parent within this new paradigm through advice columns and books. While children (or at least, boys) were learning to play and exist without restraints, permissiveness “imposed new expectations on parents regarding how they should behave in response to children's outbursts” (leading eventually, many decades later, to the types of helicopter and gentle parenting where the parent is totally subsumed to the child’s needs and wants).

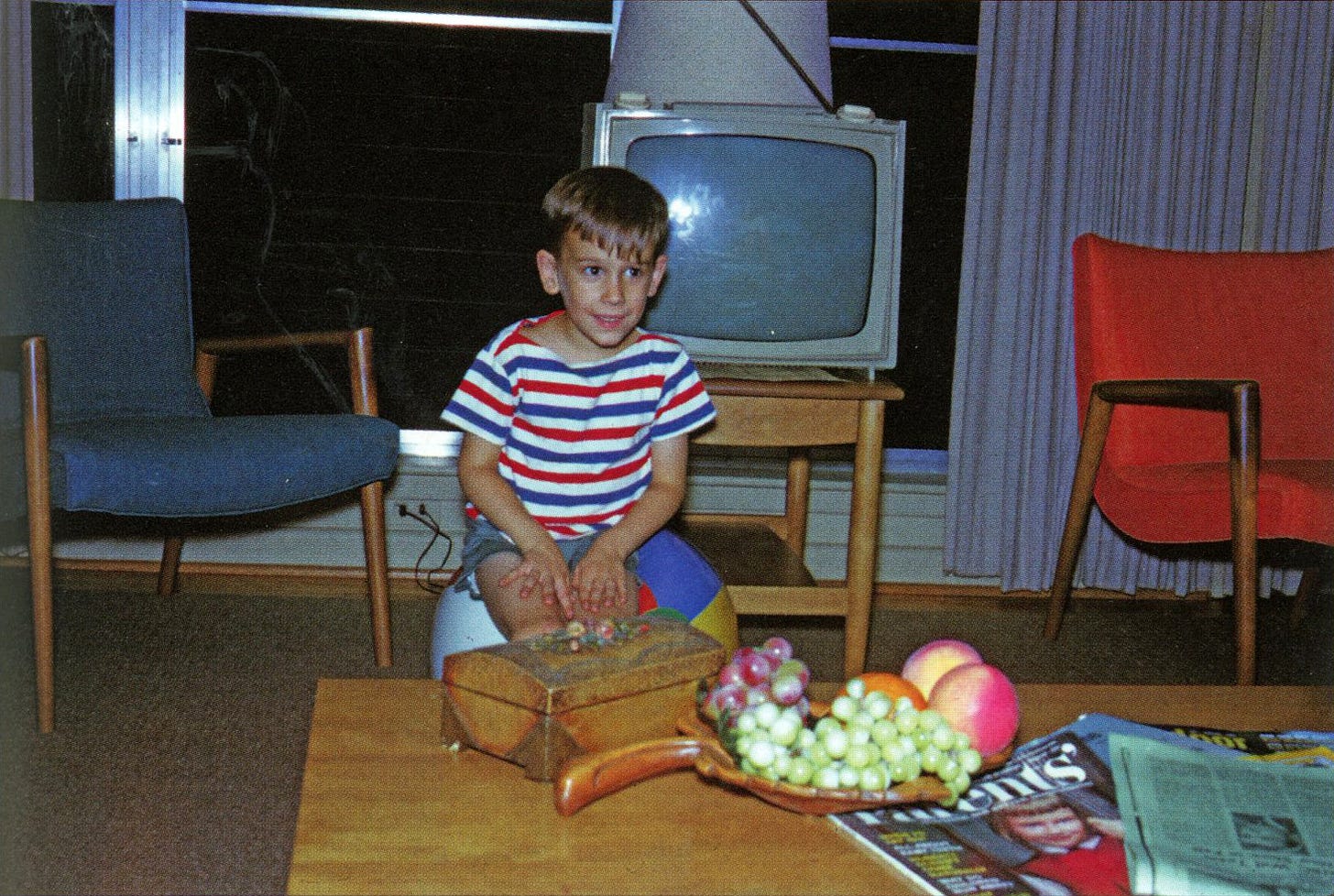

As Jenkins clarifies in our interview below, many of the media examples he uses were drawn directly from his own postwar boyhood, with him as the archetypal suburban boy in the striped shirt. From Dr. Seuss and “Dennis the Menace” to Mr. Rogers and Harold and the Purple Crayon, many of the media examples have a lingering legacy far beyond the Baby Boom generation—at least in my millennial childhood, their influence on childhood behaviour was still profound. With a chapter on permissiveness and black childhood (using Bill Cosby’s Fat Albert as the main case study), Jenkins reveals the racist nature of permissive parenting; acceptable and often celebrated behaviours for a little white boy were never viewed so positively in a little Black boy. For all the faults of this period of permissive children’s media (coming as it was out of a world rife with racism, sexism, colonialism, and homophobia), there was a great beauty to many of its goals:

“They wanted to raise children who would be more open to diversity, more willing to embrace democratic citizenship, better prepared to deal with a rapidly changing world, more capable of embracing global brotherhood, and more comfortable with their own bodies. They embraced the idea that children have rights. They saw play and learning as closely related. They sought to better understand children's emotional lives. And they sought to persuade rather than discipline children as they helped to shape the person they would become.”

The fact that so much of this media is still consumed and that their lessons feel common-sense rather than progressive shows just how normalized many of these democratic values have become, even in the face of continuous conservative, Christo-fascist assaults against them.

The Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, and Cinematic Arts at USC, Jenkins has authored or co-authored over fifteen books on many aspects of media—vaudeville theater, popular cinema, television, comics, and video games as well as “an aesthetic and strategic paradigm, transmedia, which is a framework for designing and communicating stories across many different forms of media”—and as well as on participatory culture, fan studies, new media literacies, convergence culture, spreadable media, and children’s culture. In our conversation below, we chat about how this book came together, the research process, how it made him reflect on his own childhood and parenting, his career, and how he manages to write so many books. Where the Wild Things Were: Boyhood and Permissive Parenting in Postwar America (NYU Press, 2025) is available from Bookshop, Amazon, and wherever books are sold. His website is Pop Junctions: Reflections on Entertainment, Pop Culture, Activism, Media Literacy, Fandom and More.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Laura McLaws Helms: In your acknowledgements, you state that the idea for this book came to you 25 years ago. I was just wondering if you could explain the central thesis of the project and how it grew and evolved over those years.

Henry Jenkins: It started because Dr. Seuss had just passed away, and I was teaching at MIT, the very beginning of my career. They have what's called the independent activities period in January, where people do enrichment activities. Professors do public lectures or do small classes. A colleague and I decided we wanted to pay tribute to Dr. Seuss, who had been an inspiration for both of us. We had this event where we showed the movie 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. She and I read from Seuss's work and provided some framework for thinking about it. We got that first year, maybe 300, 400 kids turned out. It was clearly a hit. We offered it again and again, for almost 20 years, I was still doing it. It became a kind of institution at MIT.

As I, through the years, read different Seuss books, read up on Seuss, I began to develop some understanding of the context he was in, and so forth. About five years in, I sat down at my cabin in North Georgia Mountains with a legal pad and just scrawled out an outline of what a book would look like that wasn't just about Seuss, but was about all of the text that had meant things to me growing up as a mid-baby boom generation kid, or an aging boy in a striped shirt, and started the idea of writing this book. I did three or four pieces from it and published them in various anthologies. Then life got complicated. I had demands on me administratively that made scholarship a little harder, and it got back-burnered and back-burnered until I moved to USC and had a little more control over my life, a little more flexibility.

I got this opportunity to have the chair of humanistic studies [Kluge Chair in Modern Culture] at the Library of Congress for a semester. That's where I was able to connect with the work of Margaret Mead and the others, and her circle. They have all of her papers there. They also had a huge set of child-rearing books that I was able to mine for things. That's where I think it deepened. Up to that point, I was writing about these writers and pop culture. I was aware of this notion of debates around permissiveness, and I had the sense that Margaret Mead might potentially be important to this project. It's when I was able to sit down with those materials that I really started to get the bigger picture of how this debate was taking place in America after the end of World War II, about what the future of the American family would be, what kinds of children we wanted to produce for what world that might emerge. That really became the focal point of this. Benjamin Spock is certainly a key figure in the book, [though] Mead, I think, swamps him in terms of the sheer number of references and the connections I'm drawn here.

Finding that stuff, digging into it, gave a rich context for the analysis of film, television, and children's books, comics that I was doing. I like to say that Where the Wild Things Were is about me eavesdropping on the conversations the adults might have been having in the other room while I was watching Dennis the Menace. It comes out of being raised in a household where my mother had a copy of Dr. Seuss in one hand and Dr. Spock in the other, or that pile of Parents Magazine on the coffee table that I found in the old photograph and put in the book. That there's just a sense that I grew up in a household that was living these debates, although from a more culturally conservative basis than some of the writers that we read. We're trying to figure out what the experts thought was the best way to raise a healthy kid who would grow up to be a good citizen of American society. Looking at this moment where there's a massive wave of publications for parents about child rearing, and there's a massive wave of media of all kinds for children, and seeing what they might say to each other, that's the essence of the book.

Laura: How did you approach doing the research and structuring it? Did you come into it with the idea of you knew what the top larger topics you wanted to focus on and then fit in the media examples, or did you start with media examples?

Henry: I start with the media examples. I always write about forms of media that touch me in one way or another. All of the examples there, for the most part, are things that were part of my own childhood. Literally, in some cases, I was going back and holding in my hand the physical copy of books that I had been read to me as a kid. In some ways, I see the book as answering the question my son would have asked me around the time I started the project, “What was it like when you were a kid?” I went back to media because I'm a media scholar and re-examined or re-engaged with things, like early Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, say, that I hadn't watched in decades, but were really interesting to look at once I developed this conceptual frame of what the permissive child-rearing ideas were.

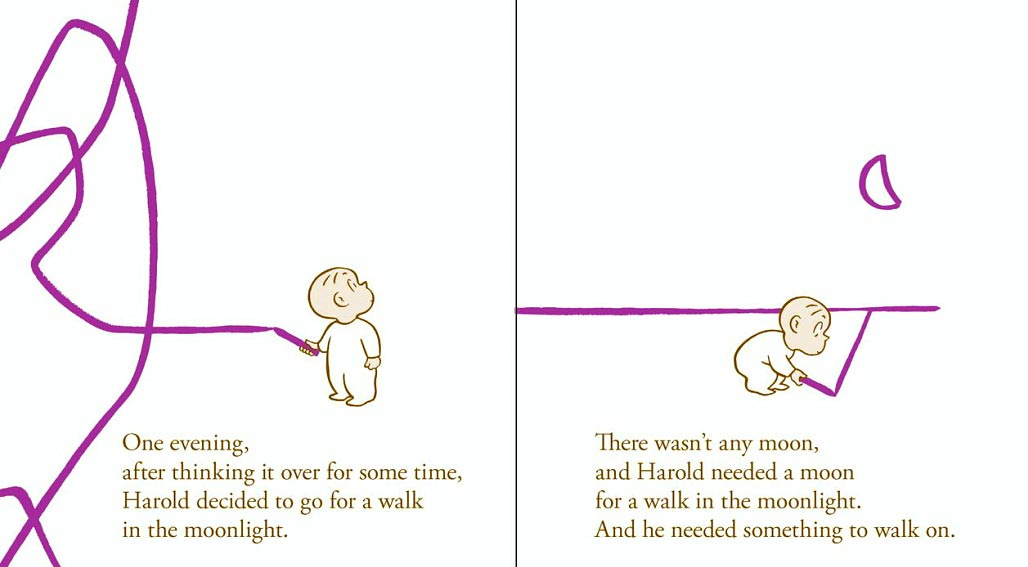

That original legal pad thing that I scrawled on at my cabin in the mountains, was mostly these are the media I want to write about: “I want to write about Johnny Quest and Lost in Space, and so forth.” There's some pieces of media that I've discovered since. Ironically enough, Maurice Sendak really wasn't part of my childhood, even though it provides the book with its title. It just seemed like a good fit for the book and evocative for people who know Where the Wild Things Were or Where the Wild Things Are. It was mostly just stuff that I remembered for as a kid and valued and treasured through those years that shaped and made me who I was.

Then the new stuff I was encountering was all the stuff that had been written for adults, whether it's Margaret Mead's columns for Redbook Magazine or Benjamin Spock's Baby and Child Care, or some of the other writers—Dorothy Baruch's incredible writing about democracy and the family—so forth. Those are the things that I discovered in the process of research. I kept finding meaningful connections between them, both on the level of the actual biographies of the people involved, like the discovery that Fred Rogers had shared an office with Benjamin Spock, Erik Erikson and T. Berry Brazelton [at Arsenal Nursery School, University of Pittsburgh], and so forth. That was a fascinating intersection. We found others like that. That cluster of writers and media makers around Dr. Seuss and Frank Capra making the propaganda films during World War II would be another one of those clusters where suddenly tracing this as an adult, you make connections that you never would have seen as a kid.

Laura: I loved the idea you wrote about with how the media being created for both adults and for children, whether it was the advice books or the children's comic books, was teaching them how to act within this new permissive framework.

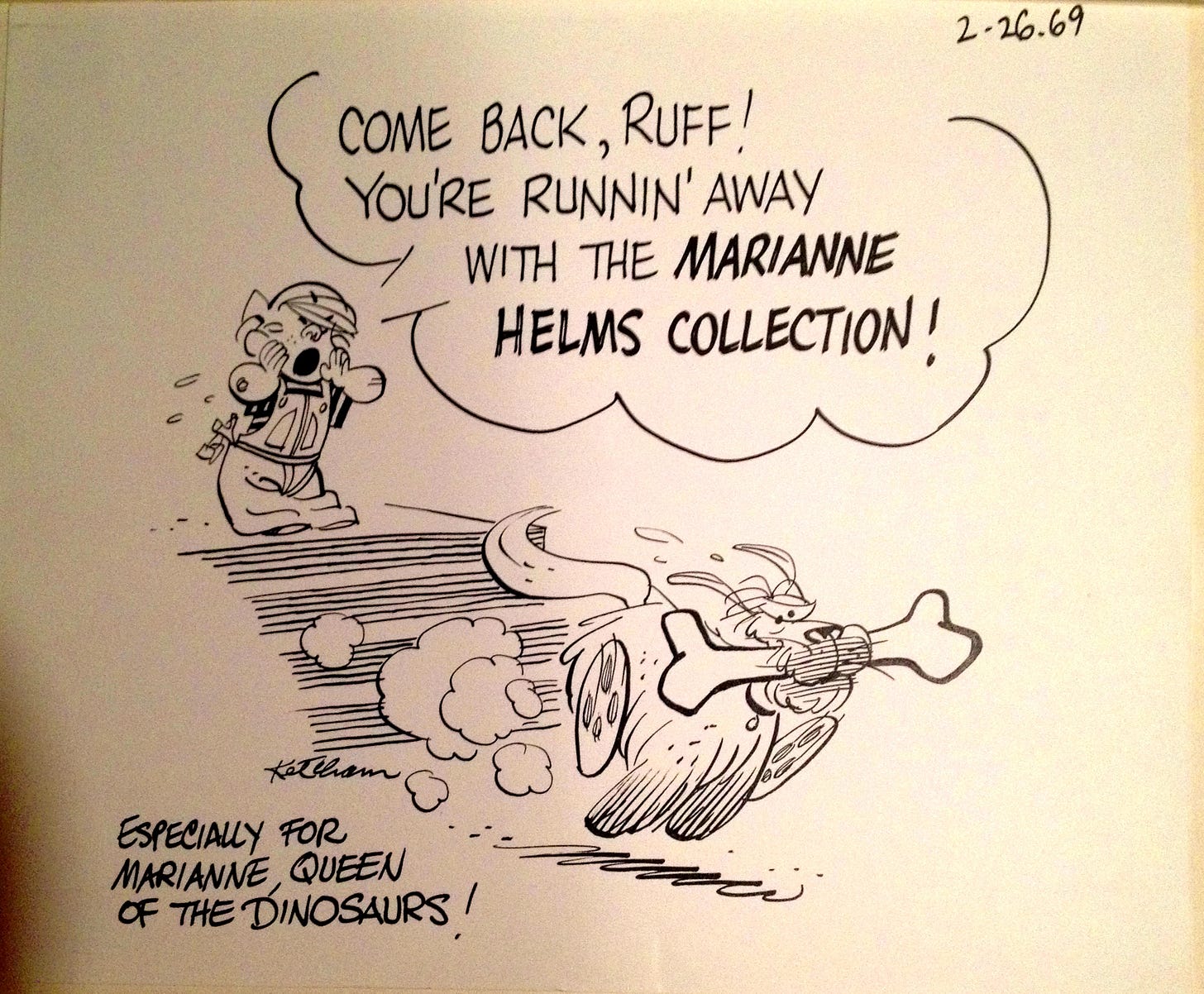

Henry: Exactly. They were teaching kids what it was to be a good child and a profoundly changed vision of America. In doing so, modeling for their parents what good parents would look like. If you look at something like Dennis the Menace, it's as much for parents as it was for kids. Again, that's a very conservative text reacting to permissiveness, but it is modeling what an ideal parent might look like; somewhere between, I would argue, permissiveness and a more traditional disciplinarian family. You see the impulse, the discipline, but [it’s] also held in check. You'll see Henry start to sputter and steam in the cartoons but holding it in and finding a more effective way of communicating with his kids. While Hank Ketchum is a critic of permissiveness, he ultimately ends up modeling something close to it in that story.

Laura: Hank Ketchum was good friends with my grandparents. When you were describing him as this arch conservative, I was like, “oh yes, he would definitely get along with my grandfather,” who was authoritarian. I found it interesting that Hank was writing this comic book, drawing this comic book that was allowing a permissiveness that I don't necessarily think that he probably allowed his son.

Henry: From what I've read, he did not have a permissive household, but probably for commercial reasons, depicts one. He knows that that's who's reading his comics. He puts the critique in around the edges, but ultimately it speaks to some of the issues that permissive parents were struggling with—the question of nudity or muddiness, or any of these other things that Dennis gets into; what is appropriate for kids to say or not say about the adult world. He ends up with a vision where the kid is not a bad kid. He's a decent kid who has a natural curiosity about the universe and just is totally honest in the face of adult hypocrisy.

Laura: Hearing the descriptions of permissiveness, especially permissiveness around boys from the time—to a Millennial mom, all these decades later it just sounds like just common sense, yet I’m aware that this vision of “permissiveness” was such a dramatic shift, especially when considering my father’s childhood, who was an early boomer but with authoritarian parents. Did doing this research change the way you looked at your own childhood?

Henry: To some degree. It certainly brought me closer to my parents, both of whom had passed long before I was writing the final draft of this. I would have loved to have shared this book with them, but I think I got some moments of confusion in our relationship much better than I did before and I hope it would for any baby boomer. I talk about, for example, in the book, the ways in which these parents wanted to transform the family to erase any chance of fascism in the family—that they wanted to get rid of authoritarianism because they were so frightened of what they'd seen during World War II. Yet, older baby boomers, older than me, the first insult out of their mouth when they’d get angry at their parents was to call them fascist. That has to have cut so deep for that generation because they had really worked so hard to eradicate that and to bring about a more democratic household, yet today, they're tarred with that stereotype of Leave it to Beaver’s parents being authoritarian and repressive, and sex was not talked about, and all of that. Most of that is simply not true from the evidence we have—they were more open about sexuality than their parents' generation had been; they were less authoritarian than their parents had been. That materialism grows in part out of the desire to give their kids the things they think kids need to grow into creative adults—witness some of the things that Margaret Mead wrote about children and creativity—and yet those are the grounds in which they're so often depicted in contemporary media. I wanted to tell their side of the story.

It's not that there isn’t criticism. That racism, implicit racism at least, is still very much present. That certain forms of sexism, homophobia, so forth. We can see the signs of that. It's not like we can exempt them from it, but we also can see they were progressive in so many other ways that we've forgotten. I hope when people read this book, they rethink that generation and think about the ways in which family building can be a progressive project and not just about traditional conservative family values, as the right has usurped the discourse of the family so often. The book ends with that tension that's still going on today between permissive and authoritarian parenting. The culture wars that are around education today, in Florida and elsewhere, are very much fought on the same grounds that the debates of the '50s were being fought.

Laura: Part of the reason I wanted to read your book so much was because I have a 15-month-old. I have a background in history, but I hadn't spent much time reading about raising a child and parenting, so I started when he was born. I was taking in the current media around parenting, all of the various advice and the culture wars around it. I have a large archive of thousands of magazines, including Redbook and similar titles. Even just flicking through them, you get an idea of parenting advice for the period. On social media, I would see people proposing supposedly new ideas and I'd be like, “This isn't a new idea,” so I started reading about the larger, historical trends in parenting advice. Just for basically my own purpose as a mother to try and make sense of the soup of it. I came across references to Margaret Mead's articles in Redbook so I went back to my issues and looked at them again.

Your book then tied all of this together with the kind of media that, while from a generation earlier, were still in the cultural consciousness in the '80s and early '90s when I was growing up. Being able to see what permissive elements had made it into my parents' childhoods and made it into my childhood in the '80s and then onwards—I really appreciated that.

Returning to what you were saying about how the idea of what boomers' childhoods were has changed: if I were to ask most people my age what they thought boomers' childhoods were like, they would definitely say they were authoritarian. They would not have thought that this was the golden age of permissive parenting. It's a lack of education, a kind of collective forgetting, I think in a way. Why do you think that has happened? Why do you think that there's been such a shift in understanding of that time period?

Henry: I think it's that counter-cultural moment where the generation gap just opened up so wide as part of what led to baby boomers becoming more distrustful of their parents and not recognizing the progressive elements of the choices they had made. Then I think the gap got fed upon by cultural conservatives like James Dobson and others of that generation who, in creating Focus on the Family, wanted to propose an alternative, conservative, authoritarian family structure and return to their ideal of what made America great. I think that process further vilified that generation and led us to a lot of forgetting.

To do the book, I had to do my own regression, because I remembered those aspects of my parents' life, but I kept finding references in books that suggested it started earlier. In the early part of the book, I'm tracing it all the way back to the progressive era, and the beginnings of the Child Study Movement and how that led through World War II and the immediate post-war period into this period of permissiveness. It was pretty clear that they were not the first to think about permissiveness, that there was something that was going on earlier. Of course, the big challenge of writing history is that infinite regress. You always think, if I go back another 20 years, what will I find? And so I had to cut it off there.

I don't know what happened 20 years before that, how far these permissive ideas go in American culture, but we can definitely see them taking root. I'd heard so many feminist critiques of [Dr. Benjamin] Spock as imposing this form of parenting that puts such high demands on mothers and so forth, and to discover that really these ideas originate with women, and that it's feminist historians, among others, who erase their contributions to our culture. They're left out of the history book, not because men didn't want to write about them, although that's part of it, but also because women didn't write about them and ignored it because it was so convenient to focus on men telling women what to do with their bodies and their children. That's an interesting story. I'm a very strong feminist, strong enough that I want to reclaim these foremothers who had progressive ideas seemingly before anyone else in the culture did and persevered with them enough to create a strong national organization of child study, where parents and scholars work together to rethink the family.

Laura: That was one of the things I was like, I need to go do a lot more reading around this. Did you find this book more personal than the other publications?

Henry: I think I'm in a cycle where the last couple of books I've written have been more personal than anything I've written before. Most of my work is personal in that I'm writing about forms of culture that touch the lives of my family or my students. That's what inspires me. But I've always kept “myself” at an arm's distance from that, but suddenly with the book I wrote before this, Comics and Stuff, I was grappling with my own pack rat tendencies, saying, “Am I a collector, a pack rat, a hoarder? How do I deal with all this stuff?” I don't have too much stuff, but I value that stuff. There's certain autobiographical undercurrents to that book. Then this book is more autobiographical by far, and I'm weaving in personal stories and stuff. I'm now doing a series of books on fandom studies, which is where I began my career. There are lots of autobiographical passages in it. This is a series of 15 books. One of them will have in it a description and analysis of my Christmas tree ornaments and my brother's Christmas tree, and things like that, my experience growing up as a fan of monster movies in the '60s and how famous monsters of film land shaped the culture, things like that.

Then, beyond that, the next book I want to do is a book on Southern identity and podcasting. As someone from Georgia, this question of “what does it mean to be a Southerner?” looms large in my mind. That's sure to have lots of autobiographical passages. Really, the cultural studies tradition I come out of has had a strong tradition of autobiographical writing, going back to our founding figure, Raymond Williams, who wrote about growing up in Wales and then going to Oxbridge and the frustrations he faced around class and regional identity, encountering not just his professors in the classroom, but the people who run the tea shop who thought they were better than him because of how they held their spoon, and his anger over that. I think that's what I'm tapping, and I think I'm on a course. Maybe it's because I'm 67 and I'm seeing more life behind me than ahead, but there's a lot of looking backwards in my writing right now.

Laura: When you were doing your research for this book, did anything come up that was not just national, but pertaining to the South and permissive culture, or pertaining to any specific areas of the country?

Henry: Less than you might think. I have that passage there where I'm trying to explain the statistics of the baby boom generation, which was going to be super dry. That's where I bring some of the most overt autobiographical stuff in about my parents and the generations of the family, and moving outward from the core city, and the hospital where I was born, and how it was an integrated hospital, but then we went to segregated neighborhoods and segregated schools. So, I tell the story there in a concise way, but I didn't really dig into it in that way.

There had to have been a tension for my parents between the fundamentalist Southern Baptist upbringing they had, which has a certain amount of authoritarian impulses embedded in it, and the advice they were getting that they read as scientific or social scientific, that that was not the best way to raise your kid. I'd love to know more about Southern Bible-reading permissive parents, because it's a possibility that got eradicated by that Dobson generation. My mother went to a stadium presentation by Dobson on Focus on the Family about the time that I was becoming a parent for the first time, and she was trying to get me to go with her and I refused to go. It turned out to be a big battle. I still have her big notebook of stuff from that, and I'm fascinated by that whole backlash, which I only give a paragraph or two near the end of the book, but I think that would be the way to get at it. How she went from being permissive with me to thinking that I needed to be more authoritarian with my son, I think, is an interesting part of that story. She never told me about any book I couldn't read, any media I couldn't watch. She was always there, thought if I had a balance of different things that I read, that it wasn't dangerous for me to be exposed to ideas.

You contrast that to all the attempts to ban books from libraries we're seeing right now. It seems like that group, the Southern Baptist group has made huge steps in a more reactionary direction since my parents' generation. I know she felt alienated by the church in her final years. I know Jimmy Carter, whose of my parents' generation, has denounced Southern Baptist, so there was this great divide that takes place in the 1980s. Someday I want to write about it, but I lived through so much horrible things in that church during that period of time that it's been hard for me to find ways to write about it. I've written a few things here and there and want to do more. It's something I need to confront.

Laura: Did working on this change the way you thought or make you think about how you raised your son?

Henry: Yes. It made me think about the choices I made. My son's now 40-something, so it's not going to change how I treat him in any concrete way, but it helped me to reflect back on some of the choices that I made that were largely internalized, like you don't just tell a kid no, you explain to them your reasoning, for example. In a pre-World War II era, of course you said no, and you didn't have to explain anything. “It's because I'm the father, damn it.” But for my generation, and probably your generation, that explaining things philosophy took deep roots. Or not to be freaked out by masturbation or nudity, or all of the things that are totally natural for a kid, particularly a pre-elementary school kid, but that we like to pretend children are sexually innocent, so therefore we don't look at that stuff in the same way. Feeling like we were trying to be more sexually open, seems like part of that as well. But I think we were permissive parents. I think I'm a permissive professor. I'm less likely to say no and be punitive of my students than to try to enable them to explore alternatives and try to understand why they didn't turn in the assignment on time or whatnot. That permissiveness extends to the roles I play. I've never been comfortable in an authoritarian role. I'm always democratic to my core, small d democratic, and permissive often in the ways I respond to the people who work with me or for me, or my students, and so forth.

Laura: How does this book fit in with your whole career? With all your other books in your career, which seem very varied.

Henry: I've written about a lot of stuff. I have an intellectual wanderlust. As I said, there is a tendency to write about culture that's close to me, but to write from a position of closeness; but this is just a book I needed to write for myself. It's probably, as I said, my most personal book because it's about how did I become interested in popular culture, ultimately. This is some of the earliest pop culture I've consumed. I've done other things on monster culture of the '60s, which might have fit in this book if I hadn't published them elsewhere. I have talked a bit about Batman '66. I have one article on Batman '66—those are my first fandoms.

Someday I might write about Mad Magazine, which certainly shaped the way I thought about media. Then I would have to think about what is it in my undergraduate years that led to my passion to film, led me to go to graduate school in cinema studies, led me to want to write about the popular side of cinema rather than the art cinema that so many of my classmates were drawn to in the '70s and '80s, so forth. This is a piece of how I became a scholar of popular culture, even though it's not explicitly addressing that. It is touching on how did pop culture shape my imaginative and intellectual life, my creative life.

Laura: By looking at your own, you've found a way to talk about a generation’s.

Henry: I think so. Not everyone had the same experience. This is specifically about boyhood. If I wrote a book about girlhood, it would be different, but I don't think I'm the person who could write that book on girlhood because I wasn't a girl, I was a boy, so I write about what I know. For boys of my generation, and arguably for plenty of girls who consume mostly boy-centric media at that time, it does speak to shared cultural experiences, frameworks that shaped our lives. It would speak to anyone.

I've done some talks at old folks' homes, which have been interesting because it meant I was speaking to people somewhere between the late baby boom and the parents represented in that book. That so much resonated with them and their eyes lit up and so forth. It's so exciting to bring those stories back and those quotes back to the people who lived it. So, I'm hoping that it will get a nonacademic readership of people of a certain age who want to reflect back on the cultural forces that shaped their lives. I try always to write in a very accessible way so that it's not just for specialist readership.

Laura: How do you write so much? You've managed to publish so many books.

Henry: I write almost as fast as I talk. You're listening to me talk now, so you can tell I talk fast. Some of it is that. I just am constantly absorbing ideas, having conversations with interesting people, and then refining my thinking through that process. By the time I sit down to write, I have a fairly polished version of what I want to write about. I just use everyone around me as sounding boards until I'm ready to write. Then I don't sit down and face a blank screen until I'm ready to write.

My rule is I want to have the first three or four paragraphs in my head before I start writing anything. If I have the opening, both the story that maybe animates the opening and then the core thesis statement and outline, then I'm on a roll and there's not a point where I'm staring at a blank screen in the writing process. That's part of it. I got as oral as I did, as accessible as I did, by reading everything I wrote out loud and hearing it come on with my tongue. I think our tongue trips over things that are tangled or whatnot. Reading our stuff aloud has gotten to a point where my writing voice and my speaking voice are very much the same.

People always say to me, you're from Georgia, but you don't have a Southern accent. I say, I don't speak with one, but I write with one. I write with a Southern accent in that I come from a long tradition of back porch storytellers who spoke in colloquial ways, colorful ways, and made stories come alive. That's the skill set that I think I use to move this stuff from being deadening academic prose into something that [anyone] might read and get something out of.

Laura: I come from an academic background, and I do read a lot of academia, but it's really nice to read a very rigorous book that is not deadened by the jargon, the academic jargon. It's enjoyable.

Henry: This is a fun topic. It would be horrible to make it anything other than enjoyable. I teach a course for my PhD students on how to do public-facing scholarship and help them find a voice that is less rigid and theory-bound, and more open to a wider audience. Many of them have gone on to do things like write op-ed pieces or journalistic writing or whatnot, blogging, podcasting to make their ideas come alive for a more broader public. I think that's such an important part of our work. We lose track of the fact that the term "professor" comes from the word "to profess", to make knowledge known. I think of my work as professing. To make it known to the broadest possible public is part of the ethical commitment of that job title.

Laura: Wonderful. This has been wonderful. Thank you.

Uncovering the History of Postpartum Depression

The way my brain has always made sense of the world and my own experiences has been through history—trying to get a sense of patterns and trends, learning the hows and whys behind ever-evolving decisions and policies. While I was suffering from prenatal anxiety and postpartum depression last year, I kept trying to make sense of my emotions by reading wh…

Caterine Milinaire's Birth

Until Caterine Milinaire became pregnant with her first child in 1970, she hadn’t put much thought into the childbirth process. As a bohemian photographer and fashion journalist, Milinaire (who I wrote about previously here) realised that having a heavily medicalized birth in a bustling New York City hospital wasn’t right for her nor her equally bohemian partner, the painter

Very interesting read!