Uncovering the History of Postpartum Depression

A Conversation with Historian Rachel Louise Moran

The way my brain has always made sense of the world and my own experiences has been through history—trying to get a sense of patterns and trends, learning the hows and whys behind ever-evolving decisions and policies. While I was suffering from prenatal anxiety and postpartum depression last year, I kept trying to make sense of my emotions by reading whatever I could get my hands on. There is a prevalence of memoirs (mostly millennial, some younger Gen X) about motherhood and postpartum illness that, while I am happy they exist and hope they are helpful for others, did nothing but make me feel more isolated; a case of the intensely personal not mapping on to the universal. When I came across Rachel Louise Moran’s book, Blue: A History of Postpartum Depression in America (published last October by the University of Chicago Press), it felt like I had finally found the initial key to grasping my situation.

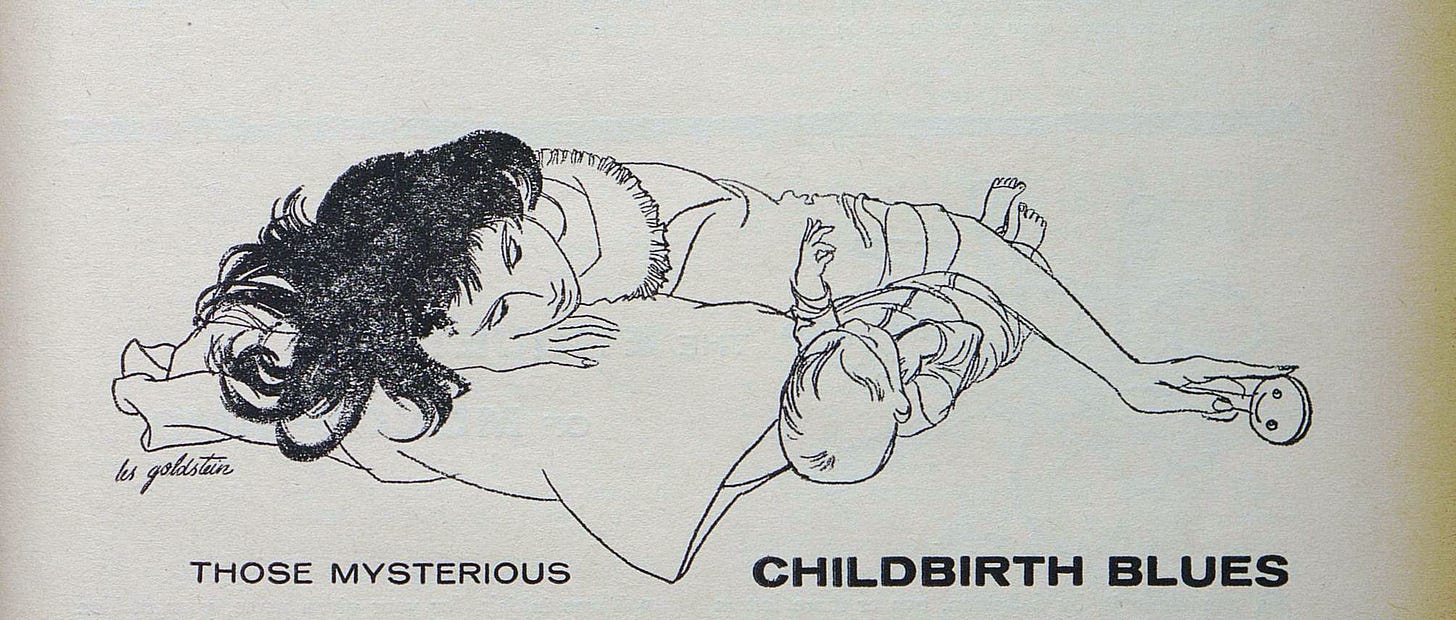

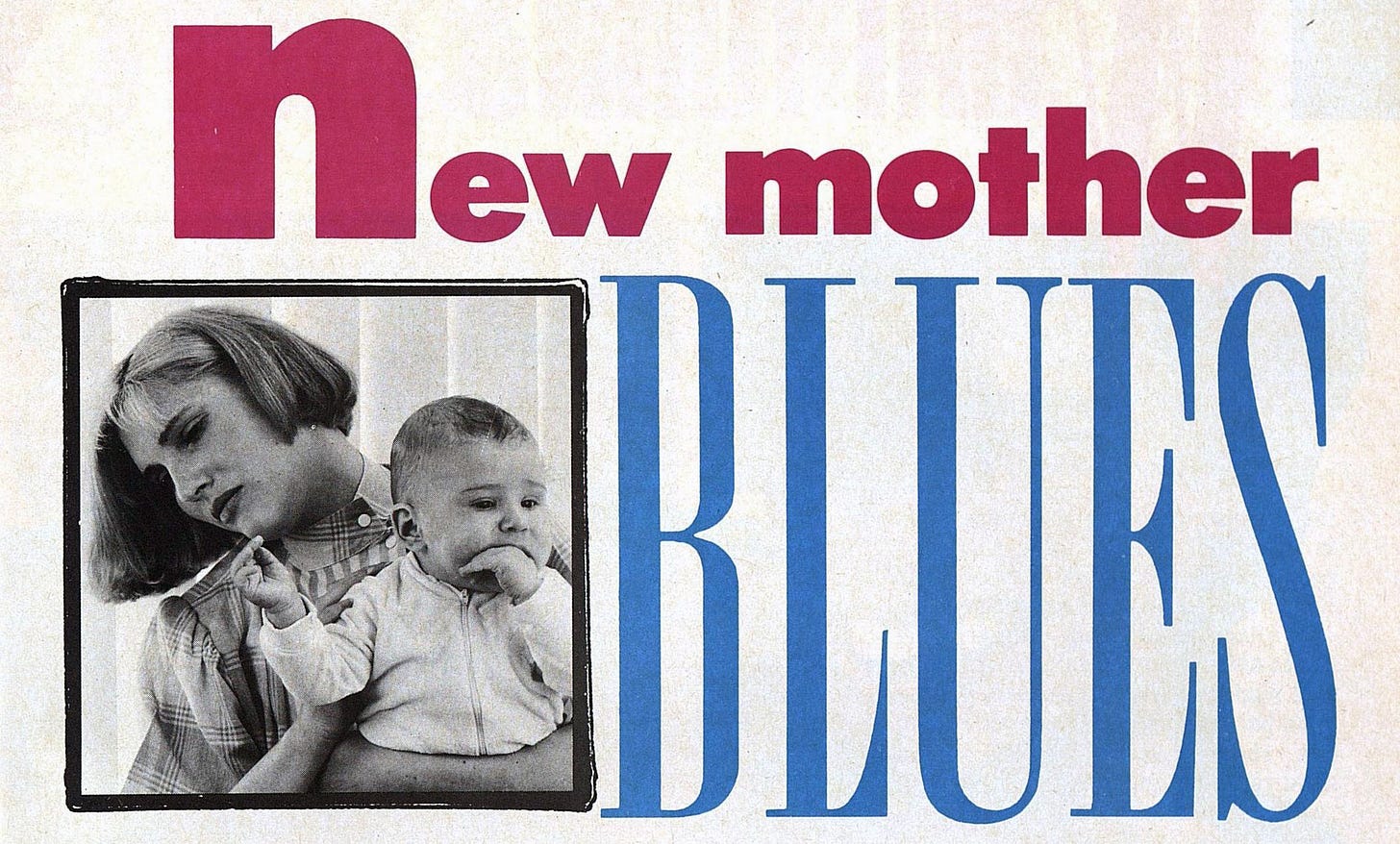

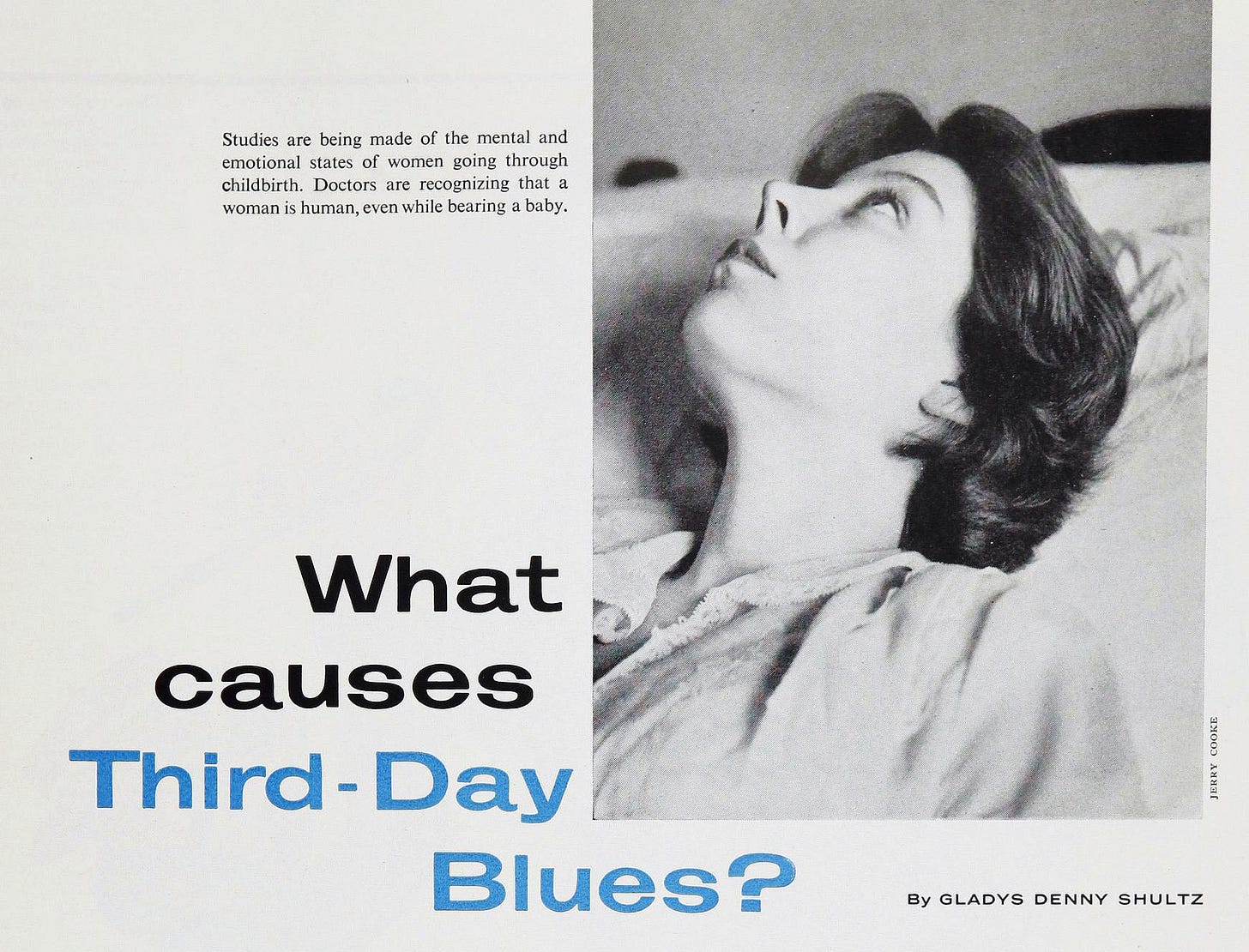

From reading 1950s and 60s women’s magazines in my collection, I knew that the idea of the “baby blues”—a short depression setting in quite soon after giving birth and passing within a few days—was a common subject of discussion at the time (often blaming the women for their sorrow). But I had no sense of how we went from there to where we are now, with the idea of postpartum depression part of the collective consciousness (though still without the research, funding, and policies to equal its renown). Moran, a historian and professor at the University of North Texas, tracks this history for the first time, with her research uncovering a path towards acceptance of postpartum illness that she didn’t expect. As we talked about a little in the interview below, she went into this project pregnant and dealing with her own complicated emotions around perinatal mental health, expecting to follow a story of over-medicalization through research in medical journals. Instead, this is primarily a story of women’s health activists—truly courageous mothers who took their own battles with postpartum depression and psychosis, founded support groups (like Depression After Delivery and Postpartum Education for Parents, later Postpartum Support International), and started to change the conversation around PPD one meeting, one newspaper interview, one TV appearance at a time. It’s also the story of medical professionals—researchers, psychiatrists, and clinicians, some of whom went into this new field because of their own PPD experiences—who chose to work closely with the activists to shift the medical establishment’s approach and definitions.

“The inseparability of the structural and the biological, the medical and the political, the exaltations and challenges of motherhood, all drew me to write this history. But the more I researched, the more I realized that this was not just a history of suffering and treatment, but one of advocacy. It is a story of groundbreaking women's health activism between the 1970s and today, and also a story of upholding the idealization of motherhood, a story of pushing against the status quo and also of pragmatically embracing the legitimizing power of medicalization and political neutrality.” - Rachel Louise Moran, Blue

As with so much of women’s health history, it’s also a political story—primarily seen within the messaging approaches of these activist and clinician groups. Torn between choosing to highlight the possible medical reasons for postpartum illness (hormonal, thyroid, or other physiological) or societal (lack of childcare, poverty, insecure housing, etc.), in an effort not to have PPD become politicized like other women’s health issues (particularly abortion), these groups decided to adopt “biology-heavy, politically neutral explanations of women’s mental health.” While this helped postpartum illness become more “official,” it has prevented any structural change from occurring; in Moran’s words, “The construction of postpartum illness in an individual, medical, and mostly politically neutral framework also limited the paths activism could take. It elevated awareness raising and non-mandatory depression screenings over challenging cultural and structural problems facing mothers.” Against the backdrop of conservative family values politics that sought to reinforce nuclear family ideals and daytime talk shows keen to focus on salacious stories of infanticide, Moran tracks the stories of DAD, PSI, and researcher-led groups like the International Marcé Society, through oral histories and archival work.

Learning about this whole history, particularly the activists’ stories, allowed me to place myself within a larger continuum of new mothers suffering; I found it immensely healing. If you are interested in the history of women’s health and women’s activism, I would highly recommend reading this. Blue: A History of Postpartum Depression in America is now available on Bookshop, Amazon, and wherever books are sold.

In our conversation below, we chat about her research process, her path to oral history, women’s health activism, and much more.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Laura McLaws Helms: Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me this morning. I found your book incredibly interesting. I had a baby like a year ago. I've been in the depths of it. When I read it, I was like, "Okay, finally, there's something that is making me make sense of everything." Thank you for researching and writing this.

What is your background in history?

Rachel Moran: Thank you. It's always brave to read it in that postpartum period. I think understandably, people who are newly postpartum are like, "I need a little more space." I know that I couldn't do some of the research at that point. Thank you.

I did my PhD in history and women's studies at Penn State. I got that degree in 2013. I've been at the University of North Texas for 10 years. I'm actually just starting a new job in the fall —I'll be a professor at Texas A&M. That's my career trajectory. In terms of the work, my first book was a history of body weight and the federal government. I did this book, Governing Bodies: American Politics and the Shaping of the Modern Physique, that came out of my dissertation and was really just interested in, “what are these moments of where citizen body weight matters enough to become something discussed in Congress?” I was just looking at those moments in that history, to think through that story.

Then at that point, I was like looking for something new to do. I was pregnant so I thought it was going to be something about pregnancy and nutrition. I was considering some different options. I have like a personal narrative about what happened, then I have an archival narrative; the archival narrative is that basically, I found these letters to the Children's Bureau. I was looking for women writing in about nutrition advice. There were these women writing in saying, it's maybe four or five letters, but people saying like, "Why doesn't your prenatal pamphlet say anything about how ill women can get after pregnancy, after birth? This can change women's lives. This is such a problem." I just remember being really struck by that, because I think we have a cultural narrative that this [postpartum depression] is a thing that started in the '90s or something like that. Because celebrities weren't telling their stories until then, [but] what came before? I was interested in, "Oh, there's very concrete stuff to follow here."

Then my personal narrative was just being pregnant, being high-risk. I wasn't physically high risk; I was just in this category of mental high risk that because of previous mental health issues, I was going to potentially have postpartum depression. That was the thing they wanted to screen for. I found it very invasive and stressful. They wanted to screen for, they wanted to have me stay on antidepressants, and they were right. I hated that, but they were right.

Also, what was so interesting and what I write about is that what I was reading as condescension and like invasiveness into my life was actually the result of like really incredible activist work to make it so that [PPD] would be on anybody's tongue. That was a wonderful history to uncover.

Laura: How did you go about finding that history? You mentioned, maybe in the acknowledgments, that you thought this [book] was going to be based on medical journals, but it's not that at all. How did you go about even learning that this story was activist-driven?

Rachel: I had some training in the history of medicine, but it's never been my central field. I was, I think, just trying to make myself a square peg in a round hole kind of thing. I was like, "I can be a proper medical historian." It's something that was just so dull. You read the medical journal articles, and there are no women. The women are just these objects of study, because a handful of the people writing are women. Most of them are men, but the woman is still very much the object, very alien.

It's very strange and hard to get at [a woman’s] voice in any meaningful way. I didn't love the idea that I would be writing about a women's health issue, and it'd mostly be about men. It just didn't make sense to me. What I started to do was first accept that I would have to interview people, because if I wanted any humans at all that were not just very paper-thin, then I'd have to do that. In the process of interviewing, I was encouraged by the people I was talking to. I was talking to psychologists, research psychologists, and research psychiatrists, for the most part. I started with the lowest hanging fruit of oral history, which is like, I know how to talk to other academics. I talked to other academics.

What's interesting about the world of postpartum depression is, as you saw in the book, it's so intertwined with the folks who are doing activist work and the folks who are doing psychiatric work, clinical work. [During] these various periods of the '80s, '90s, the activists don't want to be too radical, and the psychologists and psychiatrists do want to be doing some advocacy, or else their profession doesn't work. They end up really melded together.

Something like Postpartum Support International starts as advocacy and is very heavily clinician now, but still provides lots of direct support to women. If you go to their conference, it's all clinicians. The Marcé Society was almost no activists, but they knew some of these activists. When I'm interviewing psychiatrists, they're like, "Have you talked to Jane Honikman? She really likes to talk." I was like, "Fine, I'll call this woman." That just opened up this world of, "Oh, I can just call all the women, if I can find them." That was amazing. I think it was just a mental hurdle… when I did, the story just opened up completely.

Laura: You mentioned that you had no experience in oral history. What was it like taking that leap into a new field of history?

Rachel: We have an oral history center at UNT, which is really good. One of the coolest and worst things is that it means that most of the people whom I did oral histories with consented to have them archived. Which, as you know, as a historian, is this incredible thing. It means that the time they gave me is much more meaningful, because other people can use it. It also means that my dumb questions are there forever.

I think it was really good. It was very nerve-wracking at first. You know that when you read the greats [of oral history], they're good listeners, they tease. I don't have any of that. I definitely got better over time. I struggled, but I don't really want to do anything without any oral history again. It just seems like such an incredible tool. If you're going to do modern history, it's such a gift to be able to talk to people that I don't think I can go backward on that.

Laura: What a gift to be the person to be able to record these stories for the future and to take down these narratives. It feels like PPD that's been codified now without this understanding of where it came from. Like you said, growing up in the '90s, I was aware of it, even as a child, that there was something that went on with women. I think what your book and all of your interviews have done is track the process of how [PPD became part of the public consciousness].

As you were doing the research, was there anything that was really surprising, unexpected about the story as it unfurled?

Rachel: I was surprised a lot by the whole character that is James Hamilton. Trying to make sense of his story is something that—I'm giving it a big pause, but I'm still not done with. I suppose part of what happened is that he remains a strange enigma. He is this psychiatrist who is the father of postpartum depression. When I talk to all these women and a couple of men, they can just wax on endlessly about what an incredible, wonderful man he was. It seems like he interpersonally was, it seems like he did a lot to drive the movement in ways that to me seem also very controlling, and manipulative, but meaningful.

Then, at one point in the research process, I got this email from another historian, Benjamin Breen, and he was writing about the history of psychotropic experiments. He's just like, "So, you know about this James Hamilton guy? I've heard through somebody else." James Hamilton is just an absolute villain in his story. He is a CIA experimenter. Working at the same time, it's a little bit earlier.

Laura: Like MKUltra?

Interviewee: Oh, yes. It was all MKUltra stuff. That's exactly what he was doing—he had been in the OSS, and then he was doing mostly contracted work after that. It's wild because you go through the files, and he's getting money for thyroid research on postpartum women. I do think he genuinely was interested in it —the thyroid is the thing he was most obsessed with as causing postpartum illness. I think he was genuinely like, "This is what I want to do. If I have to do some drug experiments, I guess I will." That's just my interpretation.

Anyway, it's this interesting moment of [how] he was also a doctor in these fake mirrored apartments where they brought people up to have them take LSD or whatever. He was there not to run them, but I think to be a physician in the space. This is just very strange history. Then, because they don't have the Internet, he just meets all these [postpartum activist] women. Nobody knows. He had been in The New York Times in the '70s, testifying about MKUltra stuff.

Laura: At that time, unless you’re going through all the microfiche, you're never going to know all of that.

Rachel: He just doesn't talk about it in the '80s. He's just this godsend to women. I don't know, we all contain multitudes.

Laura: That's a fascinating, complicated person. Did doing this research and writing this book change how you felt about your own experience with postpartum?

Rachel: Yes, it did in different ways. I think both in reading so many articles and narratives, and also in talking to women. One of the neat things about talking to advocates—I didn't do oral histories with just average women who had suffered—I did it specifically with folks who ended up in advocacy roles or clinical roles. That means that they tell their story a lot. They're very good at telling their story. It also means that they have notes they hit. I just found that often in almost every story, there'd be like one little thing or something that would resonate, where just every story made me rethink a moment.

I don't have a lot of deep memories of postpartum, especially with my first. I remember talking to one of the women in the book, Graeme Seabrook. She describes her postpartum as like, she knows the specific moments that things were very bad. Then otherwise, it's all like a haze. She's like, "It's a haze. I don't care to remember." Loves her kids, all the ridiculous caveats we always say, which is frustrating. I felt a lot of that. I was like, "I think it's a haze for a reason in these interesting ways." That I think mattered a lot.

I've already told you the narrative of just totally rethinking what screening [for postpartum depression] meant. Then, almost coming in multiple steps around that. The first screening felt very condescending. Then, screening felt almost heroic, like this narrative of Nancy Berchtold's daughter giving birth and being like, "My mom did that" [Berchtold, founder of DAD, helped postpartum depression screenings become part of regular postpartum medical checkups]. Then, it’s weirdly controversial that you mandate screening. Then, even if you mandate the screening, you don't have resources attached to that screening.

We've got a mental health care crisis. You screen a woman, then what does she do? Either the OB might prescribe an antidepressant because OBs have been forced to do that a lot as a sort of stopgap measure, or you get referred, and then, can you afford care? Can you get in with anybody? You have a baby. How are you going to get care? There are so many steps. I think that that's been an interesting one to think through.

Laura: You talk a lot about how the advocates had to straddle the line between whether being political or apolitical, with being apolitical means talking about PPD as an illness—it's hormonal, it's thyroid or whatever it is causing it—then they're denying the fact there could be any social, political, cultural, structural part to it.

How aware were you of the lack of balance between these two sides before you were doing the research, and also, when you were talking to the advocates, did you get any sense that they felt bad about the over-reliance on the individual and the medical?

Rachel: Yes, I think one of the things is that at the beginning, I really thought I was going to write a more classic feminist critique of medicalization, [as] this seemed to be like, there's postpartum distress, there's clearly postpartum distress for a lot of reasons. It's simultaneously under-recognized, under-treated, and over-medicalized, right? All those things.

Of course, it's just so much more complicated than that. Part of that is the weirdness of how many things become postpartum depression. When you're talking with folks who've experienced a psychosis episode, it's just a different life experience than a mild depression, but they all are in this kind of club together. As a result, you just really don't want to be discounting the medical when the medical can be saving lives. That goes for a lot of folks in the middle of the spectrum, as it were. I am on board with medical professionals' involvement, but then also have a critical perspective on that existing at the same time. I think that complicates the story.

I think I was often surprised that some of the folks who were psychiatrists, or who were in positions where they were either prescribers or did research in that area… They were big advocates of psychopharmaceuticals and medicalization. I guess I went in assuming that they would be like, "The answer is this pill, we need more money for the pills.” That was incredibly two-dimensional on my part, because they were like, "We need childcare.” You're like, "Oh, okay, yes." I think that all of the people who are doing this research, you don't totally accidentally end up in these fields, especially when so many of their stories are people saying, "Don't go into that field. That's not a real problem, or it's not a big enough problem.” You end up in these fields with people who are really invested in women's lived experiences, so they tend to have pretty three-dimensional understandings of women. I think it was very heartening overall.

Then you do get to the next stage, which is, "Okay, so what parts are going to be funded?" The parts that are funded are going to be pharmaceutical possibilities. The parts that are funded are going to be AI chatbots. There are folks absolutely advocating for better Medicaid coverage, extremely necessary, these kinds of things.

People also explicitly told me like, “We're not going to spend our time advocating for parental leave, because maybe it's good at the state level. If you're in a blue state, you can get parental leave. But at a national level, why? But we can get this other thing—we can get the phone helpline for OBs, we can get these different things actually passed. Maybe we can get some screening," that kind of thing. Practical, but it's grim.

Laura: This book concentrates on the United States, but did you do any research into how postpartum manifests in other countries with different social structures in place for mothers?

Rachel: The case I know the most about, this just has the most writing about it, is the UK and England. There are some really interesting differences. The two main spots of difference are a history of infanticide law from the very early 20th century. It's not just England, Canada, Australia, other places have early infanticide laws. The infanticide law, basically, assumes there's likely something at play—If a woman kills her infant and there's some period, usually the first year, there's something at play. It's not necessarily a mental health [issue], they don't use that language, of course, but there's something at play to be considered. The US doesn't get a law like that, and still doesn't have a law like that, except in Illinois right now.

Then the other major thing is the NHS. Because of the health service, the NHS has home visitors. In the postpartum period, the nurse comes to your home. There's lots of writing critiquing this practice. It's invasive. It's got all kinds of issues around class. There's a lot going on. Those home visitors can catch things that are not happening in the US setting, whether women don't go to the six-week, or if they go to, six weeks is a long time, or, you can polish and present also for that visit and mask in a way that you don't as much for a home visit. As a result, you do see that about 15 years earlier, the UK was on things like just celebrities talking about postpartum illness. You see that starting in the '70s, not widespread.

We know that it was certainly a secret when Princess Diana suffered, and then later confessed. There's all of these narratives. There was much more writing, much more research, much more attention to it. You do see that, I think, the structure of health care matters deeply.

Laura: Your other work—Governing Bodies and some academic papers—has really focused on public policy, whether it's the food stamps, and/or the President's Council on Physical Fitness. How do you see this book connecting with those projects?

Rachel: It's funny because it took me a while to figure out how I was going to use my political history training for this story. There's the one final chapter [that takes place] in Congress, and they're working on the Melanie Stokes Act. That is itself just a brutal story of Melanie’s [suicide while suffering from postpartum psychosis], and then the story of trying to pass this bill [Melanie Blocker Stokes MOTHERS Act], failing, trying, failing, getting it thrown into the Affordable Care Act, never funding it. Just wild. Then I was dealing with what legislative possibilities look like. I think the big picture of the book was that it is just such a political story; figuring out how it fits into American political narratives was what was so interesting to me.

I've done so much reading and teaching around women's health activism, women's health movements, and something about postpartum illness felt like it didn't fit easily. That the advocates weren't necessarily the same people, and that the energy wasn't the same. It feels like a more buttoned-up crowd than abortion conversations, I don't know why. There's not any actual reason, except, as you unpack it, I think conversations about motherhood get very complicated and have had a historically complicated role within women's health advocacy within US feminism—what motherhood means, and how it should be managed. Because of all that, I was just really interested in the political layers of it all.

Laura: Yes, when you brought in all the family values, it made total sense that the way that you would get people to care about postpartum depression is by saying, “Oh, you have to be a good mom.” This whole good mother myth—"If you're depressed, you're not going to be a good mom. We have to make sure that you're not depressed just so you can fulfill your role in this very patriarchal society.”

Rachel: I think it still works that way in complicated ways. Even for myself, the emphasis on getting treatment, because it's for your family, so you're like, "Yes." I have been a feminist my whole life, I believe in doing things for my own sake, but [doing it for my family] is a much more compelling narrative to me, which requires a lot of unpacking. I think it's very deeply embedded in us culturally.

Laura: You mentioned that in your introduction, and I had exactly the same experience. Before pregnancy and in the early part of pregnancy, being committed to my feminist values around however [birth and motherhood] go, it's going to be fine. Then somehow these things that I didn't even realize I picked up about what it meant to be a good mother came up, and I had very bad prenatal anxiety, and that was one of the ways it manifested —this obsessive, "How am I going to be a good mom? Am I going to do a good job?" and then it continued, "I'm not going to be a good mom," and spiraling with that. Especially in our day and age, you open up your phone and the phone knows [you’re pregnant or have a baby], the algorithm knows, so you're bombarded with the products, with videos, and stories, and everything about all the things you're doing wrong, or that you should be doing, but you're not doing. It's overwhelming.

This is not directly to do with your book, but more so your whole body of work—postpartum, food stamps, the government policing our bodies, and post-abortion syndrome. I think it seems like with the rise of MAHA and RFK Jr., the government's getting even more involved in policing our bodies. As a historian who's looked at all these different aspects of it, how do you feel looking at what's going on currently?

Rachel: Terrible. I'm in Texas, so these are not new—they're not new to any of us but they're really deeply unsurprising in Texas, the way that I find many of my blue state friends very surprised.

The history of postpartum illness, because it hits this interesting intersection with maternalism and some of the family value stuff, it's interesting because you expect it to be in some ways more palatable politically. Like, "We don't want to talk to those abortion advocate ladies, but—" and so many of the folks I talk to, they say, "Oh, I know this Republican had a wife who had postpartum illness or had a sister who had postpartum illness. They'll co-sign our bill." So, there's those kinds of personal connections. Even though folks also have wives and sisters who've had abortions, they're not talked about in quite the same way. There's still lots of shadowiness about postpartum illness, but much less so, I think, because of a lot of celebrity narratives, and then eventually more media portrayals and things like that. Then the core of it being still, "We're helping the baby in this moment. We're helping the family, the baby, we're fixing this." I think that there's some of that energy behind it that matters.

Something like the post-abortion syndrome is always such an interesting story. You ask why it's not as discussed today. I think because it was always a cover story, right? It was like, "We're worried about women," for this moment where they had to say, "We're worried about women and what [abortion] is going to do to women,” so we have all these women telling their stories about how it's harmed them. Nobody has to do that now; if they want to ban abortion, they don't have to say it's going to hurt women. That's the point.

Laura: Yes, now they just say it's evil, it's wrong, it's not allowed. They have no reason to care about the women.

Rachel: I should say that narrative still exists. It's just not like what they're debating in Congress.

Laura: With your sources and archives all over the country, how did you balance that with babies or small children?

Rachel: I did the vast majority of my interviews by Zoom. I do think motherhood did shape the project. For Governing Bodies, I was like, "I'll be in DC for two months." It's unthinkable with my life now or my life while I was writing this. Archives also don't generally collect lots of women's personal stories in this kind of way. It was good that I had to find the sources in different ways.

I guess some of the amazingness [of oral history] is when you meet these activists and they've saved papers. That's, I think, the other real gift that made this possible, that made the project possible and the shape it took.

Note: Due to Moran’s research, founder of Postpartum Education for Parents (PEP) and Postpartum Support International (PSI) Jane Honikman’s papers are now in the collection of UC Santa Barbara.

Really loved this interview, thanks for sharing.