An Elegy for Gwen Davis

1934-2023

I’ve never hidden my love of trashy novels, bonkbusters, schlock, “genre books,” potboilers, whatever you want to call them—novels about beautiful people moving in glamorous circles with copious sex, name-dropping and intrigue. From this world, you can listen to my interview with Shirley Lord, who used her background as a beauty editor and socialite to write beauty and fashion-related mass-market novels. Another favourite of mine, Gwen Davis, passed away on April 4th at age 88. As there hasn’t been a proper obituary published on her, here is my elegy for Gwen Davis.

“There’s nothing wrong with a big, juicy, entertainment novel.”

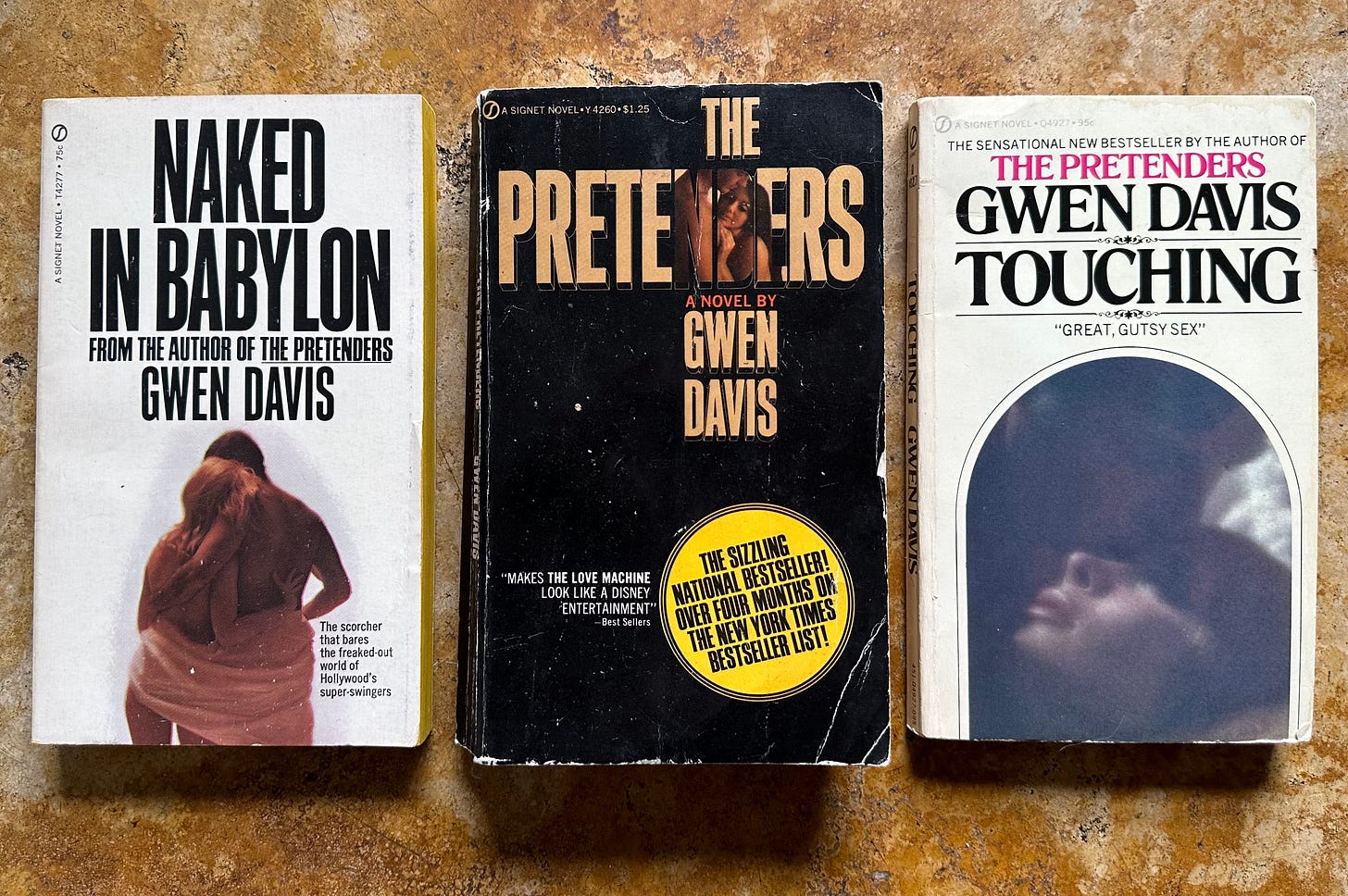

Considering how famous Gwen was and how many books she sold, it is surprising how little name recognition she has now. It was with her fifth book, The Pretenders, that she hit the big time in 1969—it was the ninth best-selling book of the year, trailing closely behind megahits Portnoy’s Complaint and The Godfather. It wasn’t her first book about Hollywood though—that would be her debut, Naked in Babylon, taken directly from her life as a young aspiring starlet in Los Angeles.

Born in Pittsburgh in 1934 (or 1936 depending on what bio you read, but I’m going with 1934 as that is what the funeral home published), her parents separated when she was young leading to “a lifetime of gypsying.” As with many of the people I write about, dates and events and ages don’t always appear to line up in Gwen’s early history. Some interviews I read spoke of her growing up in Pittsburgh—with Gene Kelly as her dance instructor—while in others she mentions spending her childhood in New York City. Gwen attended Bryn Mawr and then supposedly went to study music in Paris at age 18 (or 20) in 1954—according to some reports, there she became friendly with Maya Angelou (then touring with a production of Porgy and Bess) who encouraged her to become a nightclub singer.

Once back in America, Davis struck out for California. Writing music (several of her lyrics appeared in films in 1956 and 1957) and performing a nightclub act at the Purple Onion, Gwen’s name became a common sight in The Hollywood Reporter; judging by a nightclub ad stating her songs were about “Euphoria, Libido, Pollyannism, Cinderellaism, Hulking Brutism, Couchism,” Gwen’s themes were already well-developed. One review described her as “a comedienne with a range of talents that delighted opening night audiences. She writes her own special material and most of it is sophisticated and sharp…She’s perfectly at home on the night-club floor and should go places.”

Sometime in the late 1950s, Davis studied in Stanford’s Creative Writing program alongside Ken Kesey (he started there in the fall of 1958). Living in Laurel Canyon, Gwen fell in with an up-and-coming Young Hollywood crowd that included Dennis Hopper, Anthony Perkins and Natalie Wood; soon expanding from composing lyrics to trying her hand at thinly veiled fiction. Gossip columns in 1957 called her “Tony Perkins’ new girl,” though in a piece she wrote following Hopper’s death in 2010 Davis simply mentions having a crush on Perkins. Regardless, the group was perfect fodder for novelization. By the time Naked in Babylon came out in September 1960, her friends were her characters and she was continually attached in the entertainment press to various projects writing lyrics, music, or scripts (sometimes all three). A second novel, Someone's in the Kitchen with Dinah, about suburban swinging, came out in 1962; continuing to take from reality, apparently Kesey forced Davis’ publisher to change certain parts as he felt that he and his wife were easily recognizable. That same year Davis threatened to sue Kesey over a character named Gwendolyn in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Davis’ big break came when an idea of hers, “I Love Louisa,” was picked up in 1962 by PR guru Arthur P. Jacobs to be the first film made by his new production company; Gene Kelly, her former dance instructor, had optioned the rights first but then sold them on to Jacobs. With Shirley MacLaine starring alongside Paul Newman, Robert Mitchum, Dean Martin, and Gene Kelly, the renamed What a Way to Go! premiered at the New York World’s Fair in 1964.

Sometime during the first years of the decade, she married producer Don Mitchell. They had a son and a daughter—their daughter was born the same night that a play by Davis, “The Best Laid Plans,” debuted on Broadway in March 1966. Though called a “pleasant little comedy” by Back Stage, overall, the play was a critical and commercial failure; it closed within a few weeks. Her third (The War Babies) and fourth (Sweet William) novels came out in 1966 and 1967, respectively. The War Babies deals with the lives of four girl guides at the United Nations; Eva Gabor’s husband Dick Brown bought the movie rights, though it never made it to production. Sweet William is a satire on a coeducational progressive boarding school; MGM bought the rights and it was on the docket for 1969, but the movie adaptation never came to fruition.

A move to California was hastened by Don becoming the production coordinator for The Carol Burnett Show. Their son was born in 1968, as Gwen was busy writing a new novel—while her earlier novels had often dealt with sex themes, the sex itself wasn’t the focus. She decided, in the aftermath of the whirlwind success of Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls, to write the kind of book that “everybody would want to read.” For a year and a half, up to fourteen hours a day, Davis worked on her opus, refining her highly graphic sex passages. In an implied insult to Susann, Davis declared that she was “fed up with the non-book by the nonwriter for the non-reader. I decided to write the dirty book to end all dirty books.” Thus, The Pretenders was born. Cosmo’s review summed it up best: “Sin and sex among the jet set, possibly the potboiler of the year.” With one of the main characters bearing more than a passing resemblance to recently deceased impresario Billy Rose and another awfully reminiscent of talent agent Sue Mengers, The Pretenders captivated as an entertainment guessing game; with Hollywood Gwen’s social circle, she had much to draw from in her personal life. The Los Angeles Times reviewer remarked, “There is something for everyone: Sex (hetero, homo, group, solo and a), murder, suicide, voyeurs, drugs, blackmail, debauchery, perversion and more.” It reached the best sellers list in its first week with offers for the film rights nudging above $1 million—proof that Davis was correct when she told the LA Times, “You know, nobody really wants to belong to the beautiful people, but they do want to read about them…” When the book was banned in libraries across America and Ireland, it just brought greater publicity and more sales.

“Gwen comes on strong, with the speed of a rocket. She is supercharged, vibrant, brown-haired, brown-eyed, looks as sexy as one of the heroines in “The Pretenders,” her novel which was on the best-seller list for 19 weeks in 1969.” – Mary Engels, Daily News

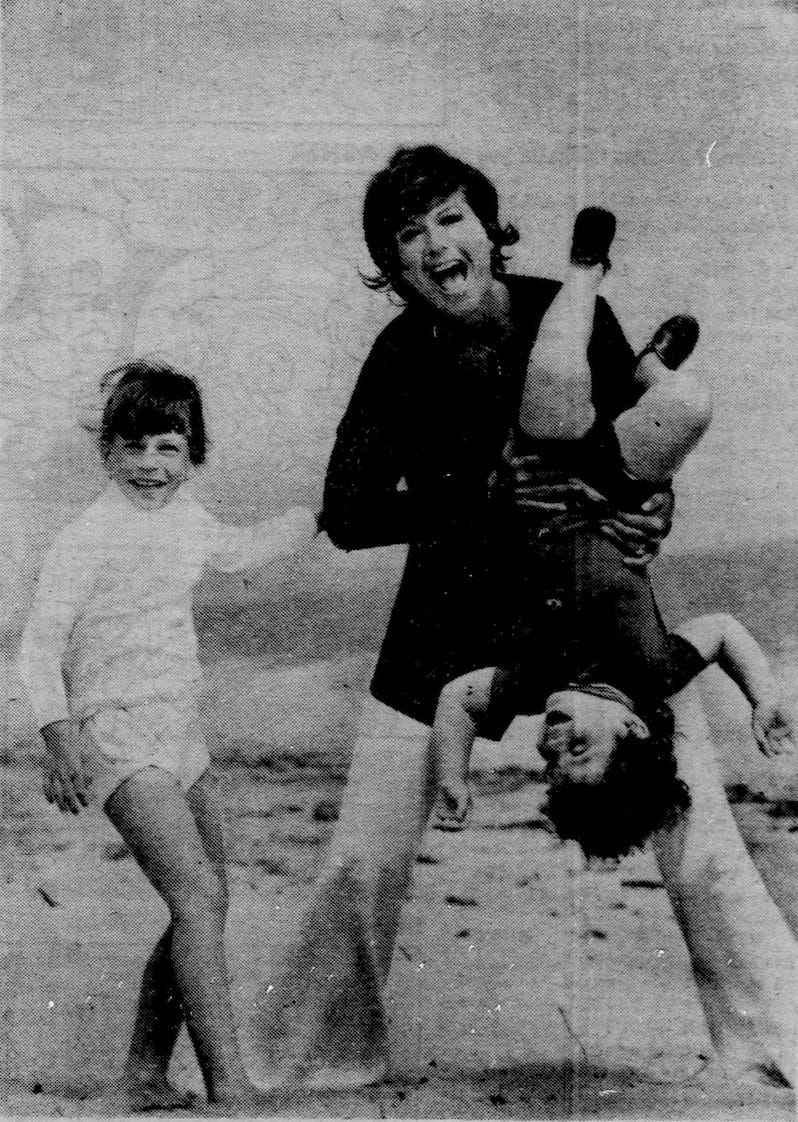

The funny, outgoing personality that had made her a hit on the cabaret stage was equally suited for television, with The Pretenders huge success translating into copious interviews on local and nationwide talk shows; for several years, she was a common guest on everything from breakfast shows to Johnny Carson and Merv Griffin. Davis managed to balance being a celebrity “authoress” with being a Beverly Hills wife and mother—all possible, she said, due to the unwavering support of Don who never quarreled over long hours writing or weeks away on book tours. The pair were noted for their annual Academy Awards party, with Gwen long remembered as a doyenne of the Coldwater Canyon scene.

For her sixth book, she again returned to lived experience—in order to write about “the all-American bored female in search of who-knows-what,” Gwen “visited the places and activities women go to try to fill those empty days, such as extension courses, groups (charitable and political), psychoanalysis, group therapy” and, most importantly, a 20-hour nude encounter put on by a Topanga Canyon shrink. Unstrung by the experience, she fictionalized it for Touching (1971)—hoping to both expose the dangers of encounter therapies like this as well show people that it is okay to express themselves. “People are frightened of a totally open woman because we’ve been playing games in this country for so many years,” Gwen told the press. “I hope my book can have a profound effect on American life. Maybe it can help to free people to the extent that they wouldn’t be so frightened to express their feelings.” Carol Burnett (in a Ray Aghayan-Bob Mackie calico midi) hosted the launch party Upstairs at Le Bistro, attended by much of the Hollywood cognoscenti.

Though Davis did not reveal the leader of the nude encounter she attended, both her book and associated interviews were so disparaging that it's probably no surprise she was sued for libel in what would become a landmark case. Before that occurred, Gwen published an inspirational novel (à la Jonathan Livingston Seagull) about tragic lovers, Kingdom Come in 1973—The Godfather producer Al Ruddy purchased the movie rights. That year she also published a book of poems, Changes—followed the next by The Motherland, a 500-page three-decade political saga “depicting the innocence, bravery and narcissism” of America during the 1930s through 50s. In 1976 she was sued for libel and published a book of aphorisms about women’s lives, How to Survive in Suburbia When Your Heart’s in the Himalayas.

In January 1977 Paul Bindrim, a psychologist whose nude encounter group Davis had attended eight years earlier, won a libel judgment against her and her publisher, Doubleday. Bindrim charged that she libeled him “by portraying his encounter in an unfavorable manner, invaded his privacy and violated a contract she had signed promising not to write about the marathon.” His attorney was able to match a tape recording of the session Davis attended with passages from Touching; he was awarded $25,000 from Davis and $50,000 from Doubleday. Gwen Davis appealed; the California appeals court upheld it and when the case went in front of the Supreme Court in December 1979, they chose not to review it. Doubleday then sued Davis, as she had promised them that nothing in the book was based on life. Bindrim v. Mitchell reopened questions around truth vs. fiction in novels and how much a novelist can take from people they know, leading to a spate of similar libel cases.

Somehow none of this slowed down Davis’ fast-paced publishing schedule. In 1977, she published a Hollywood whodunnit, The Aristocrats, followed in 1979 by Washington DC drama Ladies in Waiting: “A riveting story of beautiful women trapped by their ambition and loyalty in a world made by men for men.” The Supreme Court rejection led Gwen to refocus on earlier formats; “I’m working on a movie screenplay and a Broadway musical. I’m just trying to put this case out of my mind,” she told Women’s Wear Daily. One script became the movie Better Late Than Never (1983), starring David Niven and Maggie Smith; another became the telefeature Sea Glass (1982). The musical Sylvia Who? was picked by acclaimed producer Mike Merrick and was supposed to go into rehearsal in 1982, but it never made it to the stage—below is Rosemary Clooney singing one of the songs from it.

Davis’ husband Don died of cancer in 1984 at only 45; as her website bio explains, his death left her “to discover what I was meant to do for the rest of my life.” She kept writing and took to traveling and living all over the world; according to her website she “lived again in Paris, then Venice, London, Weinheim (Germany) Hong Kong, Beverly Hills (now and then) New York, and, most recently, Bali.” More novels followed throughout the 1980s and beyond, all mostly in the same vein: Marriage (1981), Romance (1983), Silk Lady (1986), The Princess and the Pauper (1989), Jade (1991), West of Paradise (1998), Lovesong (2000) and Scandal (2011). A picture book about a Yorkshire terrier living at the Hotel Bel-Air, Happy at the Bel-Air, was published in 1996. Her peripatetic lifestyle led her to become a travel writer for the Wall Street Journal Europe in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and until 2018 she regularly updated a blog about her adventures, Reports from the Front. Her life was long, varied, and filled with both adventure and incredible productivity.

Though her novels have little literary merit, Gwen tried her hand at almost every genre and format of writing—from screenplays to plays to poems to bon mots to novels of every type. Over her career, she published twenty-one books, eighteen of which were novels. Gwen was always on my list of people to interview for my podcast; her interviews from the 1970s are filled with gossip and good stories, with Gwen always coming across as an incredibly warm, happy and funny person—I regret not acting on my desire earlier. If you are looking for a good beach read this summer, don’t hesitate to pick up a copy of The Pretenders or Naked in Babylon for a little salacious Hollywood fun.

Great piece. Sad that she's gone but what a ride she had. RIP, talented lady.

Gwen was my writing teacher for a weeklong fiction workshop in Paris. She was so kind to me. I was just looking her up to see how she was…so sad to learn she has passed. I had no idea her history was so illustrious.