Getty Miller's Journey through American Mass-Market Fashion: Part I

Louisiana, FIT, and the Sixties

The counterculture fashion magazine Rags, which ran for 13 issues from 1970 to 1971, became known for its explorations of personal style as found on the street and as used by subcultures. Only in the debut issue is there really any form of an editorial, where the photographs are explicitly selling all of the clothes on show. For Nancy Hall-Duncan, to be considered a fashion photograph there must be a commercial element and a “fashion intent.” This editorial “Sitting Down,” photographed by Stan Papich, celebrates “a whole new erogenous zone to explore when below the knee skirts are slit to expose leg,” as shown on a coterie of hip downtown New Yorkers. Bethann Hardison models clothes by Getty Miller for Pranx and Willi Smith for Digits—both less expensive, mass-produced youth brands—posing alongside Miller, Smith, and fellow designer Bill Alvira.

It was the photo of Getty Miller and Bethann that captivated me. “MICK JAGGER . . . may have his dresses, but Getty Miller is into skirts.” As the caption alludes, Getty shares more than a passing resemblance to Mick—a fluffy mop of hair, full lips, an intense stare behind aviator glasses, and a lean body with shirt unbuttoned low on the chest. I’d come across his name many times in Women’s Wear Daily in the 1970s, always designing for juniors’ lines, but his name faded from its pages by the end of the decade. Who was this Getty Miller and what happened to him?

When I first started researching Getty Miller, I was not sure what I expected to find. All I knew were his designs for various Seventh Avenue manufacturers in the seventies, his rock-star looks, and that he had died of AIDS in 1992. What I uncovered was a rural Louisiana childhood markedly different from the glamorous New York and Hollywood worlds he ended up in.

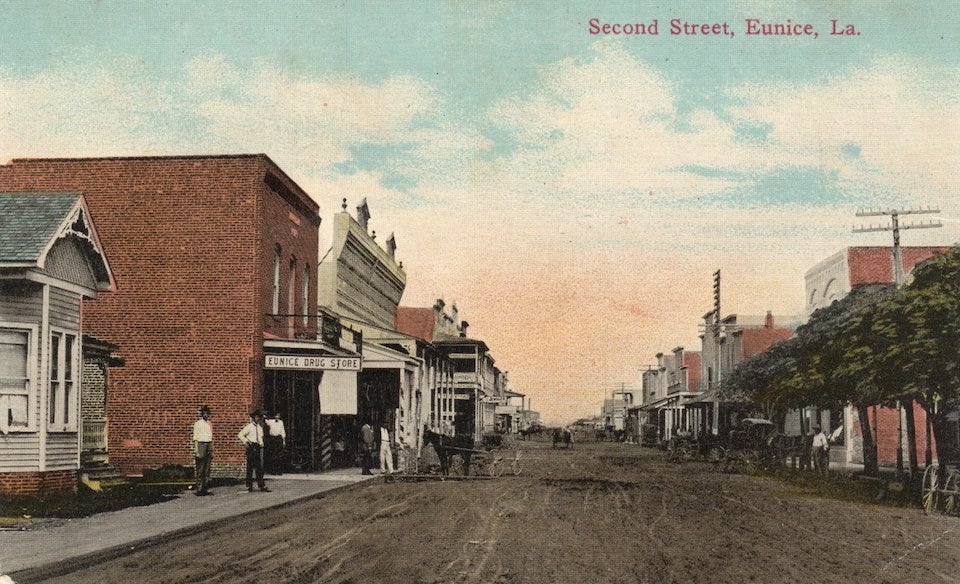

Getty Thomas Miller was born December 2, 1940, the second son of Getty “Shine” Miller and Lydia Billeaudeaux Miller in Church Point, Louisiana. The son of farmers, Getty “Shine” Miller was a “well-known cattleman throughout south Louisiana” who at the time owned a commission barn (“a barn where the owner or trainer acts as an intermediary (or ‘middle man’) in a horse sale or lease, and they charge a fee (a commission) for their services,” though his specialized in cattle) in the unincorporated community and census-designated place of Lacassine. In 1952, Miller moved his family to his hometown of Eunice when he leased the Livestock Exchange there. Called the “Prairie Cajun Capital of the World,” Eunice was, and is, a small town marked by a long and remarkable history. Founded by Acadian exiles from Nova Scotia who settled on Louisiana's prairies, around Eunice developed a distinctive cultural mix of Cajun, Creole, and cowboy.

In the middle of this mélange, Getty Miller Jr. was raised to be a cattleman like his father. Living in such a small town, he supposedly read the Sears Roebuck catalog for entertainment. Following his older brother’s footsteps, Getty participated in the local 4-H Club, learning to raise steers, and exhibiting them at livestock shows. In February 1957, his steer was named the Reserve Champion at the 18th annual Junior District Fat Stock Show in Lake Charles. Getty and his steer were front page news on The Crowley Daily Signal—a geeky-looking Getty clad in a large cowboy hat over a close-cropped head, dark-rimmed glasses, a plaid cowboy shirt, and jeans. A month later, sixteen-year-old Miller brought that Hereford to the Louisiana State University livestock show, where it won first prize. The following year he won first again at the Lake Charles show. Returning home from the state show (where his calves came in third and fourth), he wrote an essay on his 4-H experiences for the local paper. Stating, “I often wonder where I would be today if I hadn't enrolled in the beef project,” Getty went on to describe how throughout his “two years in beef I've won 21 ribbons and six trophies. I have won $203 in prize money and received $8,110.40 for the sale of four steers” (that’s $2,241.30 and $89,546.11 today, adjusting for inflation). He continued, “I cannot find words to express my feelings for the things I've learned in 4-H and the beef project. I have learned so much and met so many wonderful people. If 1 hadn't taken this project I'd probably still wouldn't know the difference between a scrub and a champion.”

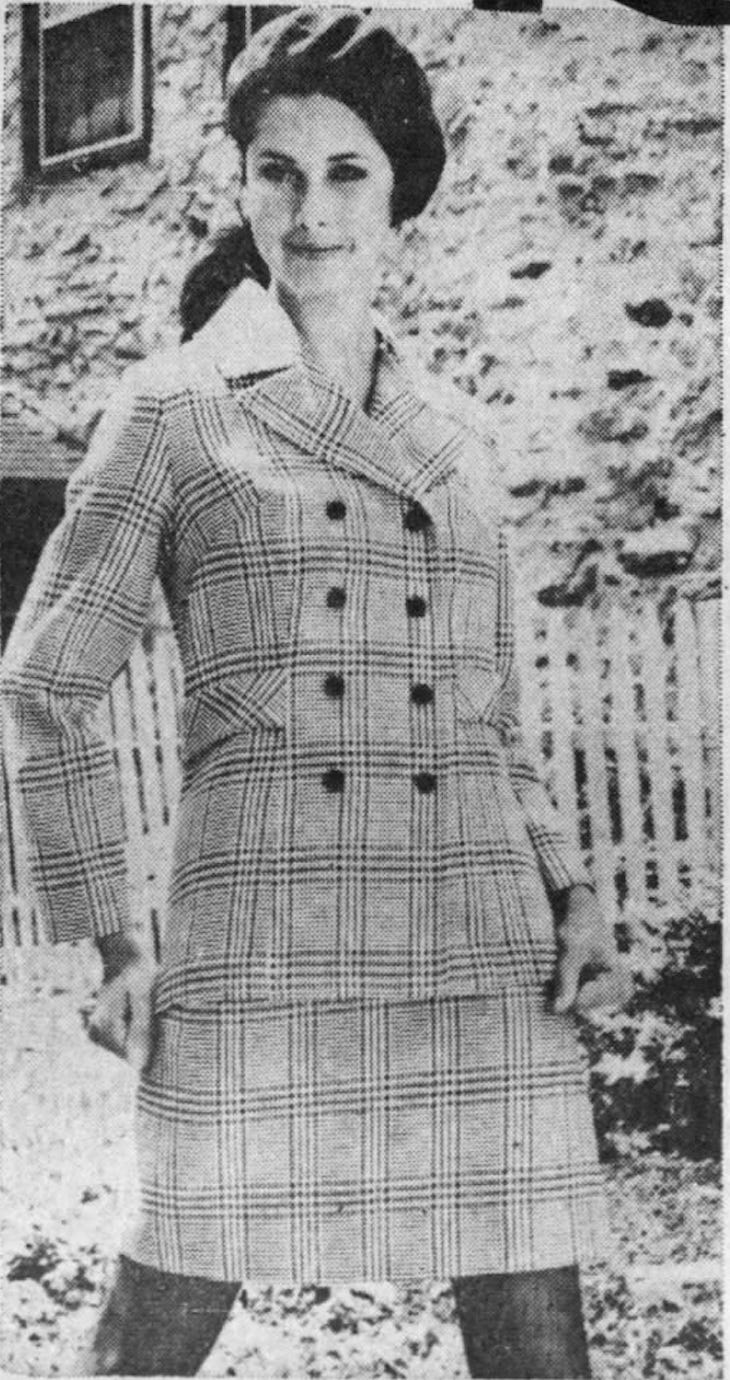

After those two years, Getty Miller Jr. retired from raising steers, reappearing in the local press in a 4-H baking club and then as a member of the Southwestern Louisiana Institute Orchesis Dance Club once he started college there in the fall of 1959. It appears that at Southwestern Louisiana Institute (now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette) he was majoring in Dance—a sharp turn from the cowboy dreams of his father and brother. After a year and a half there, he transferred to the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York—using his steer-raising savings to fund his dream. Following graduation, he worked briefly for the Jeanne d’Arc junior division of L’Aiglon, before joining the junior dress firm Rue 39 Cie in September 1965. When Rue 39 Cie filed for bankruptcy in 1966, he continued to jump from firm to firm and took a tour of Europe before landing at Glenora in 1967. Glenora was founded in 1950 as a “new name with years of Know How and experience in producing man-tailored lined suits at popular prices,” but by 1953 appears to have transitioned to Glenora Casuals, which focused on “co-ordinated skirts and separates at moderate prices.” While he appears to have been the second designer, under Levino Verna, Miller did travel around doing trunk shows, presenting his houndstooth and Glen Plaid suits for Glenora at department stores across the country.

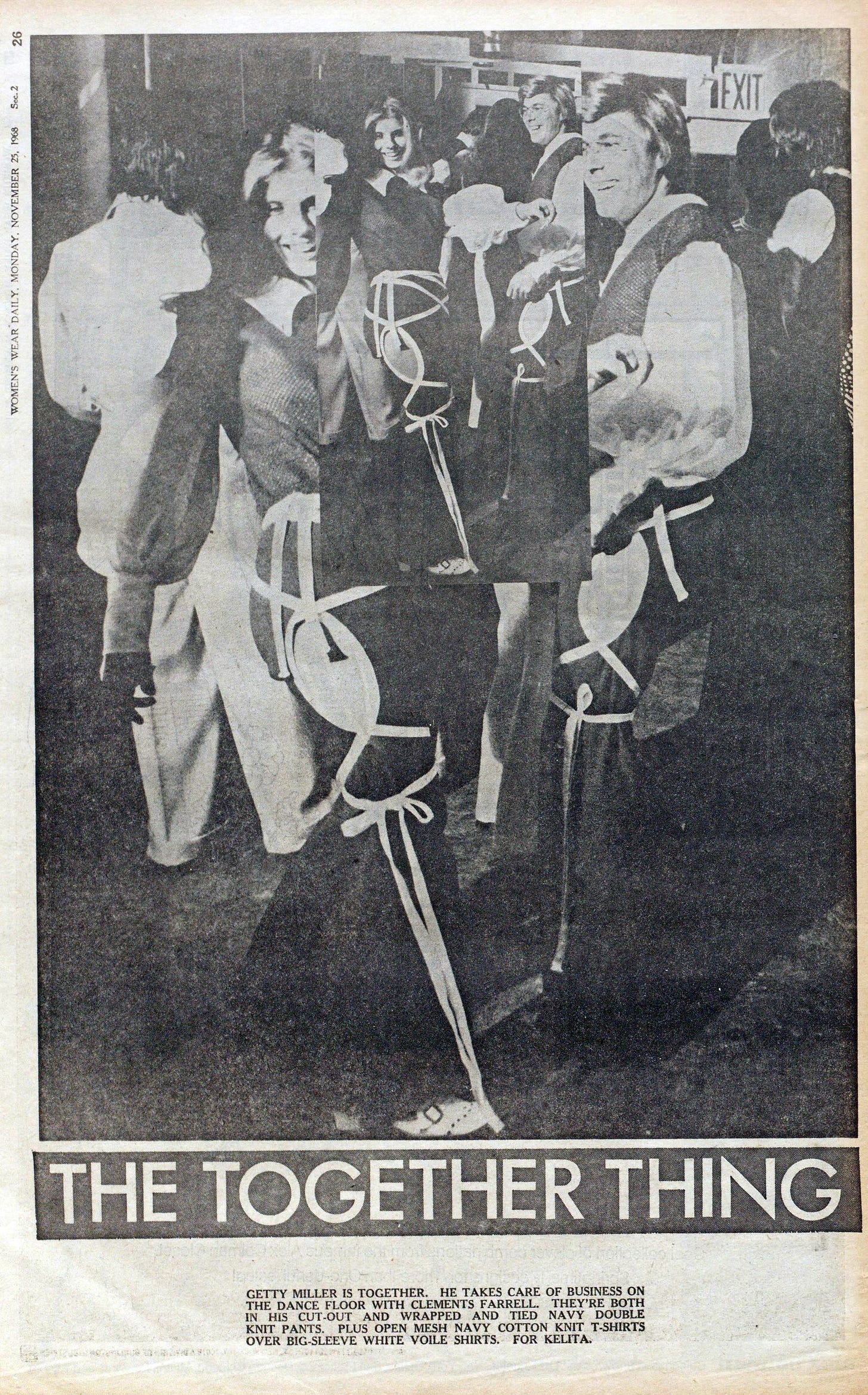

In 1968, Getty Miller stayed on at Glenora—designing for both the main line and Glenora Jrs.—while also taking on the role of head designer at Kelita, specializing in “crazy printed pants, very inexpensive and mostly for the teenybopper set.” Moving away from the suits that defined his early work with Glenora, Miller’s new designs for both companies began to regularly appear on the pages of Women’s Wear Daily. What is clear from the sheer breadth of his designs is his ability to synthesize and rework the counterculture clothes his hip friends were wearing into mass-market designs—the flea market and army-navy finds of his pals and hippies on the street were streamlined for the masses of America. In 1968 and 1969, Miller designed everything from crushed velvet 1940s style suits to a “Meditation Suit” with a Nehru-collared long jacket and pants, to a crepe Middy blouse and a faux snakeskin “PantsJumper” tunic over matching pants. There is no one look or message, other than a true understanding of what elements of psychedelia, nostalgia, and hippie culture could be translated for teenagers from Omaha to Orlando. How about a “gaucho outfit in synthetic cowhide” of midi-length chaps, long button-front vest, and ruffle blouse? Or a backless cotton pique tunic over matching slim pants?

“Recent events have made people stop and think more about what's happening in the world around them and where they stand. As they discover more about themselves they will more and more take an individual approach to things, including fashion. If anything the new fashion approach will be away from conservatism . . . away from mass trends.” – Getty Miller, Women’s Wear Daily, June 12, 1968

Getty Miller’s Robert Redford-like shaggy mane of blond hair, handsome face (filled out and sculpted, far from the pimply teenage steer-raiser), and aviator glasses quickly made him a favored designer to appear in newspapers alongside models in his clothes. All-American enough to appeal to parents, while youthful and just edgy enough to appeal to teenagers, Getty seemed to have it all. These early newspaper appearances never mentioned his background in Louisiana, simply concentrating on his work as a hip Seventh Avenue fashion designer. One of the few times when there was any overlap with his past was in 1968 when he took inspiration from Reverend Ralph D. Abernathy’s Poor People’s March and other civil rights protests for some clothes for Kelita. “It’s amazing how fashion ideas spring from anything these days,” he told Newsday. “The Poor People’s March inspired me and the idea started germinating to do a group of clothes in conjunction with working class people.” Not dissimilar from the clothes worn by his parents in his teenage trophy photos, Miller schemed up “handyman overalls in faded blue denim with a red bandana print handkerchief peeking out from one of the pockets, striped denim reminiscent of the type used for railroad engineers' overalls fashioned into vests and culotte skirts for warmer weather and slightly more elegant-looking navy denims styled into double-breasted tunic-length vests and flaring cuffed pants.” For him, these styles were the way forward; “Many of the expensive clothes are exciting and beautiful," he continued, "but it's not what's happening. It doesn't reflect the spirit of the times and, another important consideration, the youth of this nation can't afford to spend a lot of money for styles."

Continues this weekend…

"When you dress up you feel good": Counterculture Fashion & Rags

As I was putting together my talk on the counterculture fashion magazine Rags for a symposium tomorrow (in conjunction with the book launch of the new academic volume, Fashion in American Life), I reread the publisher’s letter in the first issue and felt it was rather prescient.

Outside Fashion

When we think of the late sixties counterculture, all of us conjure up in our minds images of their fashion looks. Dress was such an essential part of countercultural identity, regardless if one was a hippie, a Hells Angel, a Black Panther, or a feminist. The mass media, then and now, reinforced how each of these groups was supposed to dress. The ideolo…