Empresses of Seventh Avenue

A Conversation about the Birth of American Fashion with Fashion Historian Nancy MacDonell

Edna Woolman Chase, Carmel Snow, Elizabeth Hawes, Claire McCardell, Marjorie Griswold, Dorothy Shaver, Lois Long, Virginia Pope, Eleanor Lambert, Diana Vreeland, and Louise Dahl-Wolfe… Some of these names are still well-known, others remembered by the most passionate fashion history fans, and some forgotten. All of these women were integral to the advancement of the American fashion industry—and their story, interwoven and collaborative, is being told together for the first time.

Empresses of Seventh Avenue: World War II, New York City, and the Birth of American Fashion is a new book released yesterday by Nancy MacDonell, a fashion historian and journalist. In this book, Nancy charts the rise of what fashion designer Elizabeth Hawes called “the French Legend”—“the widespread belief that all beautiful clothes were made by French couturiers and all women wanted those clothes”—and how all the diverse parts of the American fashion industry responded to the fall of Paris, leading to the development of “The American Look” and New York’s rise as a fashion capital. Nancy correctly lays that ascension on the work of those women listed above—fashion editors, designers, department store buyers and heads, journalists, and photographers. As she writes, “All shared a common belief: that fashion could be both beautiful and democratic. In their insistence on this truth, the women who lifted American design onto the international stage were revealing their ideals. Their resilience changed how we all think about the clothes we wear.”

As someone who has read most of the primary sources Nancy used, I thought she did a wonderful job bringing them all together and showing just how interconnected these women’s worlds were. An enjoyable and fascinating read, Empresses of Seventh Avenue brings to life the American fashion industry of the 1930s and 40s and the women who ruled it.

The other week I spoke with Nancy about her background, the inspiration for this project, her research process, why these women are so important and interesting, and much more.

Order Empresses of Seventh Avenue from Bookshop, Amazon, Barnes & Nobles, or pick it up from a local bookstore.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Laura McLaws Helms: I really enjoyed your book. I'd love to chat with you about it, starting with just a bit about your background as a fashion journalist and fashion historian.

Nancy MacDonell: I guess I would say that I've always been interested in fashion, really for as long as I can remember since I was a child. What people wear, how they put themselves together, and how trends disseminate, that sort of thing. I like to quote Anne Hollander, who said that fashion is the art form that we all participate in. I get annoyed when people say or suggest that fashion is frivolous or unimportant because I don't think that's true at all. Fashion says a lot about the way we live. It's a great form of self-expression. I don't know any powerful or influential nudists. We all wear clothes.

Laura: Definitely. Did you go into fashion journalism straight from school?

Nancy: Though I was always interested in it, and I was always interested in history as well and I knew I wanted to write, but I somehow didn't put the two things together until I was in grad school. A professor said, "You'd be good at writing about fashion." It was like, I've been waiting my whole life for someone to tell me that yes, I would be good at this. I really got into it from there. The first time I went to graduate school for journalism was at the J-school at NYU. I stayed on in New York and worked in magazines and worked as a freelancer. That's how I got into fashion journalism.

I worked at Nylon. That was the magazine I was probably associated with for the longest, a job that I loved. I worked at style.com, when it was Vogue online, before Vogue had a really big presence online. It was really the only place that you could go to look at every single Marc Jacobs look from spring 2002 or whatever it was. Then I really became a freelancer after my daughter was born. I've been freelancing ever since. I write a column for the Wall Street Journal called “Fashion With a Past,” in which I look at current runway trends, but examine them through a more historical lens. I've written for The [New York] Times, for Elle, for a whole hodgepodge of magazines.

Then, as I'm sure you're aware, the bottom really fell out of magazine journalism in the mid-2000s. I started thinking about what else I could do. Most people go to work for a brand or they become consultants, which is great, perfectly valid. I think I always had a bit more of an academic bent. I did almost think of becoming an academic, teaching art, history, or English literature. I just wanted to feel like I had more control over my life. I didn't want to have to go take a job at the University of Saskatchewan or somewhere. I wanted to be able to choose where I wanted to live. I loved living in New York, so it became journalism.

I started thinking about other things that I could do with my interests. I had a chance meeting with Patricia Mears at The Museum at FIT, who I was interviewing for a story I was writing. It really sparked an interest for me in becoming a historian. That's what really led me to it. I did, like you, the program at FIT [MA in Fashion and Textile Studies: History, Theory, Museum Practice].

Laura: Wonderful. Now you teach at FIT, right?

Nancy: I do. I went back and I teach in the program. I've also taught in the history of art department. It's like the final segment of the history of fashion is contemporary fashion, which picks up in the '90s and goes to now. That's really been my career. For me, it made sense to teach it. The other class I've taught is the History of Fashion Photography because I'm very interested in fashion journalism and fashion imagery and fashion iconography. That one also made sense for me.

Laura: That's great. What led you to choose to write this book on the birth of American fashion and the French legend and this particular part of it?

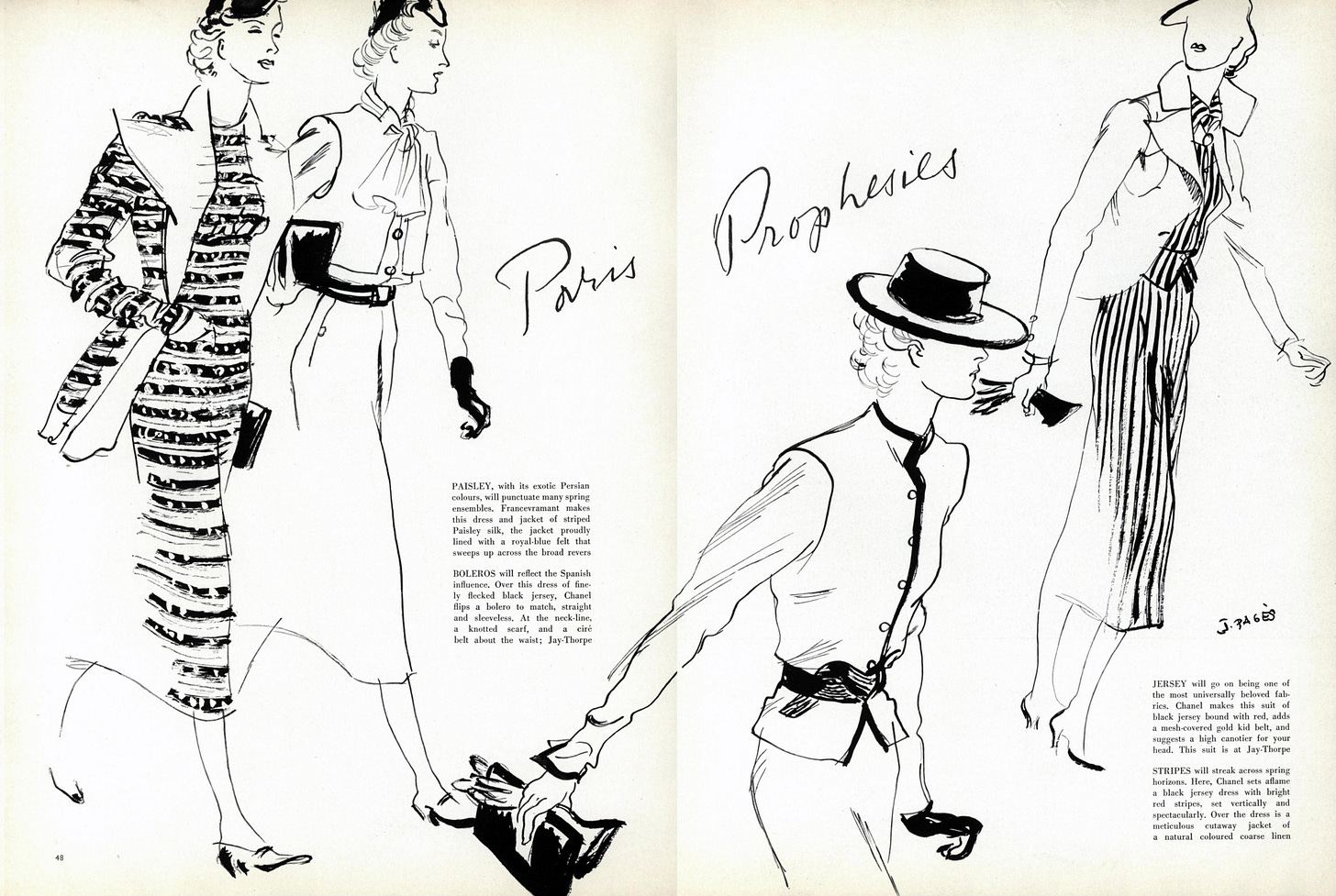

Nancy: I guess I should define the French legend for anyone who might not be familiar with it. This was a concept that existed before Elizabeth Hawes gave it this name. She defined the French legend as the idea that all beautiful clothes are made in the atelier of French couturiers or French designers and all women want them. As you know, this was how the fashion world functioned up until that point. Everyone copied Paris.

I think this idea still has a lot of currency if you think of the French girl that becomes a thing every summer or this idea that Paris is so central to fashion. Being a journalist, I have a contrarian streak. If you tell me something like that, I just start thinking, "Really? Hmm, let's look into that. Let's see if that's really true." I wanted to explain that the French legend, it didn't just happen. It's not that the French are better at fashion just because they're French. It was this very deliberately constructed idea that originated at the court of Louis XIV. He and his first minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, really turned France into the world's first global luxury brand.

At the same time, the period between the wars, between World War I and World War II, has always fascinated me, in large part because it was such a great time for women designers. This idea really came together for me when I was reading Lois Long, who I wrote my thesis on at FIT. I really fell in love with her writing and the idea that she was championing American designers. I just thought there was a bigger story to tell there.

Usually, when people look at fashion history, they focus solely on designers, which is certainly valid. Designers can't get their ideas out there on their own, which I know from working in the fashion industry, that there are a lot of other things that come into play. I thought it was a really good story and an important story to tell.

Laura: Do you remember what was the impetus? Like, “Actually, maybe this would be a good idea. I want to devote the next few years of my life to this.”

Nancy: I had known about all these women [Edna Woolman Chase, Carmel Snow, Elizabeth Hawes, Claire McCardell, Marjorie Griswold, Dorothy Shaver, Lois Long, Virginia Pope, Eleanor Lambert, Dianna Vreeland and Louise Dahl-Wolfe] separately and they all had really interesting lives. I realized they all knew each other. Of course, they did. They were working in fashion at the same time. This makes sense. Fashion is still a small world. It was really a small world in the 1930s and '40s. I just started to think about how entwined they were.

It wasn't just a fashion story. It's really a story about women's lives at this point when women were really coming into the workforce, building careers for themselves, which all of these women did. It fascinated me that fashion was a really great place for women to do this, whether you worked in a department store or for a designer or in advertising, it was something that women were able to excel at.

Laura: I liked how you brought together these women from the different segments of the fashion industry, and showed how they collaborated and worked together to create the American look.

Nancy: Yes, which also just didn't happen. It was constructed as well.

Laura: First, how did you approach the research? You just said that you did your thesis on Lois Long.

Nancy: I think I probably read every issue of WWD that came out between 1930 and 1947, which was an incredible resource that I can access because I teach at FIT. I can get lost in that stuff forever. I love reading old newspapers and old magazines, especially those that have to do with fashion. I guess those were really my primary sources, reading the fashion magazines, reading WWD. I was lucky in that quite a few women profiled wrote memoirs. Maybe this was just a more illiterate era. People were relying on the written word. Those were also wonderful sources.

Because they all know each other and these things are happening at the same time, there is some cross-referencing that I could do. The primary sources were wonderful. Really, I could have spent three years just doing that, but I had to buckle down and tell the story. As you said, I thought that to tell the story of American fashion effectively, it was important to look at all these different facets, to bring in some journalists, to bring in a retailer.

You cannot tell the story of American fashion without Eleanor Lambert, who really invented the profession of fashion publicist and how fashion publicity still works today. That story needed to come in. Some people had to be winnowed out, unfortunately. The book would have been too sprawling, but I think that that's what made sense to me. That's how it made sense for it to be done.

Laura: Of the women that you profiled, the ones that I knew the least about were Virginia Pope and Lois Long. Are Lois' papers anywhere? Were you able to get into her own writing beyond The New Yorker?

Nancy: Not really. She is mentioned and there are some letters of hers to her editors at The New Yorker in The New Yorker papers, but I think she was pretty private. No, there wasn't much there for me to find other than what she wrote about herself.

She didn't just write about fashion. She started out as the nightclub writer. This was during Prohibition, so it was essentially a job that was about doing something illegal. Every night of the week, she would go out and she wrote about her experiences in nightclubs and reviewing them. You really get a sense of her as a person then, that she was this sort of Zelda Fitzgerald character at The New Yorker. She and her assistant had desks that were very far apart, so they'd roller skate back and forth, or if it was really hot, she might strip down to her slip when she came in to write her column. This was long before air conditioning. Not too much of a personal nature, no, unfortunately.

Laura: The way you talk about her makes her sound like an incredibly fascinating person.

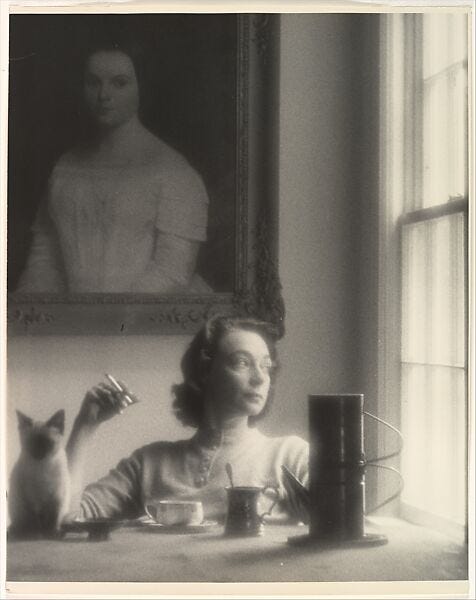

Nancy: Yes, I think I fell a bit in love with her. I identify with her because she's a fashion journalist, and to see someone doing it so well, because her writing is wonderful. I do want to stress, she did this all without any illustrations or photographs, because The New Yorker did not run any photos until Tina Brown became the editor in the '80s. Her column was not illustrated, so she really had to describe things well and succinctly, and she really excelled at that.

As her editor said, she invented fashion criticism. She wasn't just describing things or writing in the imperative voice that fashion editors at magazines like Vogue and Bazaar used at the time. In classic fashion journalism, “This is what you must do. You must wear taupe from head to toe, and this is this.” She was really doing a service for her readers in that she was really analyzing, and she was also helping designers, which is what she did for American designers. She would say, "Don't get caught up in trying to copy the French. That's not what you are good at. Lean into what your strengths are."

Laura: Yes, and I guess by writing in a publication like The New Yorker, making fashion be seen as more of a serious thing.

Nancy: Yes, yes, and she wasn't beholden to advertisers the way writers at Vogue and Bazaar were, because she really had a lot of freedom. If she thought something was not up to par, if the quality was not good, she was not shy about saying so. In one of her first columns, she said, "You can buy Chanel if you want, but it's going to fall apart." Maybe American women need to smarten up about that. She was very forceful with her opinions. She loved Chanel, but when Chanel didn't do well, she let her readers know that.

Laura: There should be definitely more of that.

Nancy: Yes. Wouldn't it be great if The New Yorker revived that column? I think it would be really fun to read.

Laura: Definitely. As you were doing the research or pulling it all together, was there anything particularly surprising or fascinating that you just uncovered or connections that you didn't know about before?

Nancy: I knew that the French legend was really baked into the American industry and that people just thought that's how things should function because this is how we've always done it. I was really surprised at some of the reactions after the fall of Paris. It's like people's hair was on fire. They didn't know how they could move forward without the French. There was someone who was quoted in WWD saying, "Don't worry. We have at least six months' worth of French fashion to copy and then we'll figure something out."

It was like the sky was falling down. They didn't know how to work. Not everyone, but a sizable portion of the fashion industry, they just couldn't imagine how to move forward. There was this real fear that, "In September, American women just wouldn't buy any clothes. What do we do then?" Which was, of course, not what happened.

Again, I knew a bit about this, but how seriously the Nazis took fashion—they were sociopathic murderers and yet part of their plan for world domination was to move the haute couture from Paris to Berlin. Yes, it was very interesting to read that kind of thing.

Also, just small things that popped up, like before nylon, as you know, silk stockings were like the gold standard of hosiery. American women wore them very casually. They wore them all the time, even though they were probably $2 a pair, let's say, which was a lot of money during the Depression. European visitors were gobsmacked by this because in Europe or in the UK, women saved silk stockings for best. It was not something you wore every day. You wore cotton lisle, not very attractive, but American women, they had the largesse of the ready-to-wear industry, which was a world leader. There was nothing else like it anywhere else. They really benefited from this.

Laura: Of the sort of designers that you profiled, is there one that you particularly love? Is this where your personal taste is for fashion?

Nancy: I love both Claire McCardell and Elizabeth Hawes. I am more familiar with Claire McCardell's designs because there are more of them. She was a ready-to-wear designer. She's still so regularly referenced by designers all over the world. Learning more about Elizabeth Hawes, of course, I read her book, Fashion is Spinach, she was just such an iconoclast. She was a fascinating person. It's such a shame that people don't know more about her.

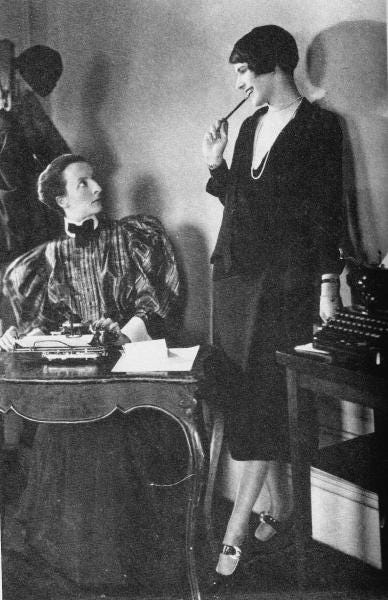

I hope this, in some small way, rectifies that because she was the first superstar American designer. Yes, I think most American people in the fashion industry even have never heard of her. She was a big name in the 1930s. She was a couturier, really. She had her own ready-to-wear house in New York. These were expensive clothes. She dressed many women in the arts or women who maybe shared her leftist political beliefs, but not entirely.

Then she shut her house down in 1940 at exactly the wrong time. I want to go back and slap her and say, "Don't do this." Then she was blacklisted by the FBI because she then became a labor activist, union organizer. She's a fascinating person. Her writings about how the French industry worked in the 1920s and '30s with so many people trying to steal designs because they didn't want to pay for them, it's a really fascinating glimpse into how the industry worked.

Laura: Yes. I love her, I love “Fashion is Spinach” and “Why Women Cry: Or, Wenches with Wrenches.” She's always been, I think, one of the most fascinating people in fashion, and the way that she could zoom out and look at the whole industry and see how it was all working together in a way that I don't think a lot of fashion designers are able to.

Nancy: Yes. When you read Fashion is Spinach, you think, "Well, of course," but she was really looking at things on a very granular level and then turning them into this narrative that carries you along and really reveals how the industry was working. I think you're right, especially when something's happening at the time, it's not so easy to be able to step back and see things for what they are.

Laura: I've done more of my research on the '60s and '70s, and the designers are so in the weeds, trying to make sure that the money in and out is working, that everything is working, that you have the time to do the creative work you want. It's hard to be able to see what is actually happening in the industry and see where you fit within it as a whole.

I thought it was interesting how most of the book is '30s, '40s, and the war, and then you jump forward to the Battle of Versailles in 1973. What was the reasoning to have that skip forward in time?

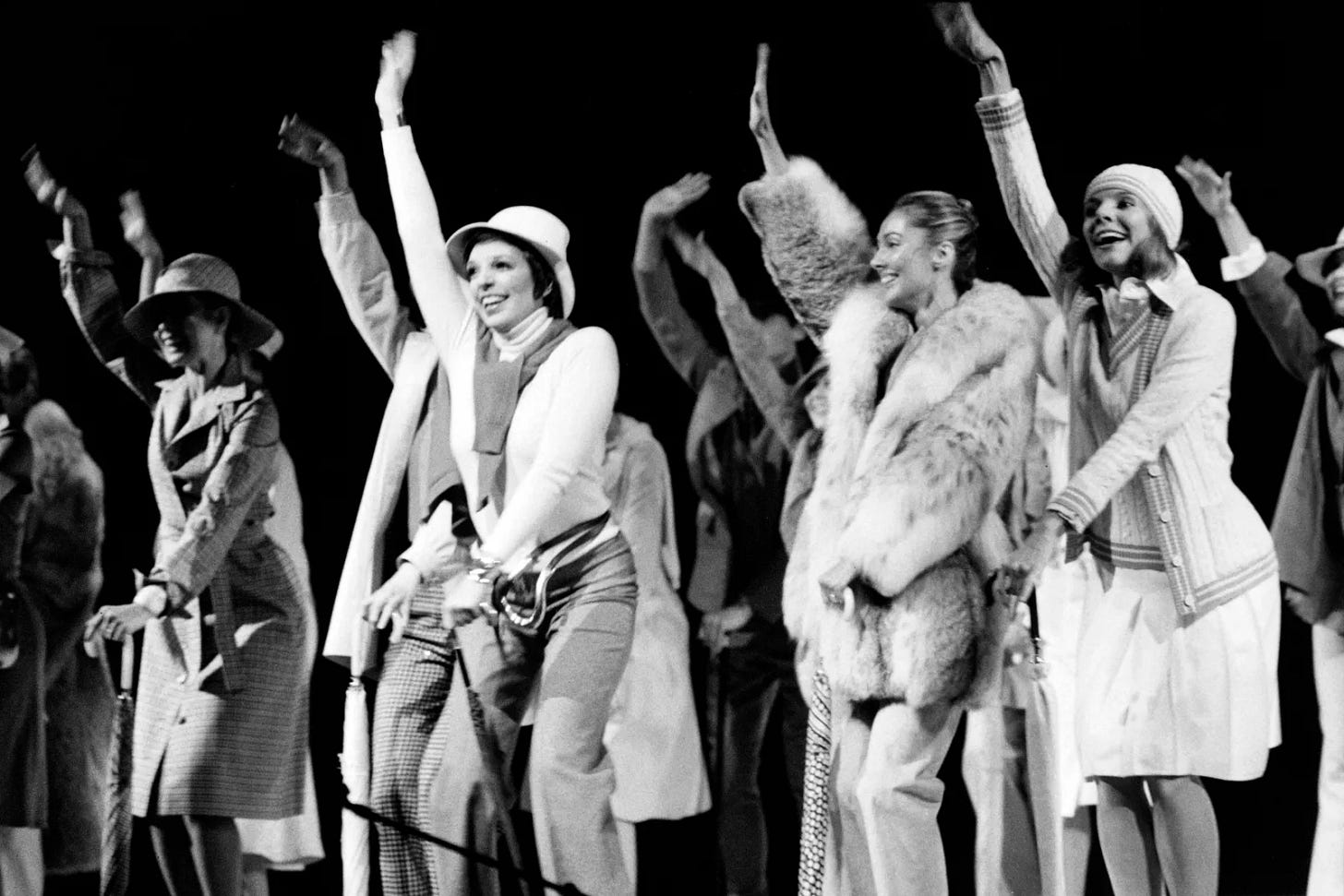

Nancy: I think the Battle of Versailles was just so important for American fashion. World War II was when American fashion came into its own, but the Battle of Versailles, I think, was when the French finally acknowledged that they had worthy adversaries or worthy colleagues on the other side of the Atlantic. It just took a very long time for the perception that American designers were second-rate to go away.

Bill Blass, who I mention in the book, who was at the Battle of Versailles—he was a great sportswear designer. He used to tell people he was in advertising when he first started out, because it was more socially acceptable. By the early '70s, this had changed, and he was chumming around with his upper-class clients. For designers to come out from the back room and be treated as celebrities, which started in WWD with the way John Fairchild started covering the industry—it was very gossipy about the lives of these designers and the women who wore their clothes.

I think because the Battle of Versailles demonstrated so forcefully that American designers were good designers, it was important to include. By 1973, the haute couture, which is what we're really talking about when we talk about Paris fashion in the '30s and '40s, was already a shadow of itself. It had 15,000 customers just after World War II, about 3,000 in 1973, a few hundred now. The haute couture fashion shows are like advertising exercises for brands now. They're not really about getting those clothes made.

I also wanted to have the continuity of Eleanor Lambert organized it. She worked until she was 99 years old. It's really quite incredible. There was that throughline of Eleanor Lambert. I really wanted to show how far American design had come. It was a good way to point out that no one expects American designers to be copyists now as they have been expected to even before then.

Laura: What do you think has been the impact of these various women, the “Empresses of 7th Avenue,” on American fashion today?

Nancy: I think the American look really came to define the way we dress today. We don't wear the formal clothes that haute couturiers had made. Life is faster. It's more casual. Fashion is much more democratic. That is perhaps the most important quality of all. Fashion is for everybody now. It's not this closed conversation that happened in certain very rarified circles and everyone else wore a knockdown of something else.

I think that's the most striking thing, is how the American view of fashion came to be the world's view of fashion, in part because after World War II, the United States had a much larger international presence, not just politically, but culturally, in terms of the arts. Fashion was part of that. The American look became a really international—it was internationally recognized. It came to influence the way everyone dressed, which Dorothy Shaver of Lord and Taylor foresaw. She said, "One day, it's going to be a compliment to be told, 'My dear, you look like an American.’" I don't know if that exactly is true, but that's how she put it.

Laura: I think probably at one point it was. Now, American is seen as slightly negative, but the majority of what everyone wears around the world indeed is some trickle-down of American sportswear.

Nancy: Look how important sneakers became to every fashion brand. There was a while where if you didn't have a hit sneaker, you just were not… you weren't a player.

Laura: Yes, it's interesting. I was listening to a podcast the other day, a fashion podcast. They were talking about how New York Fashion Week is becoming less important. It's become shorter and fewer shows and how it's really that Paris and Milan are the top ones, with New York and London moving down. Obviously, New York Fashion Week is still important now. It's not like it's dead. You're talking about the beginnings of this, of trying to make it into a real consolidated industry, right?

Nancy: Yes. Yes.

Laura: Then it went to a high peak for half a century, basically. Now so much of American fashion is just most of the casual stuff. It's less about fashion shows. It's all really fascinating the way that the business works and has worked.

Nancy: Yes. I think because there is not the American equivalent of LVMH or the Kering Group, these giant luxury conglomerates that run huge brands like Dior, like Louis Vuitton, like Gucci. There is not an American brand on that level, but there are so many interesting American brands that are smaller and that are producing clothes that women really want to wear. I'm thinking of brands like Kallmeyer, Maria Mcanus, Rachel Comey… The Row on a more expensive level… but it struck me that the women I know love these brands. They love these clothes and they wear them. I don't think that's just an American thing. There are other brands like that in other countries, but it started with these brands in the U.S.

I think American designers need to lean into what they do well and not get caught up in, again, being like Paris. The cities have different strengths. The designers, I think, have different strengths. I don't think New York Fashion Week will go away. That story comes out constantly, no one's coming, no one's showing. There's still that idea of like, “it's commercial.” Like that's a bad word, but if you don't sell the clothes and people don't wear them… it's not just marketing. Yes, things look good on Instagram, but you need to have people wearing your clothes.

Laura: Definitely. I grew up in London, so a lot of those clothes were not commercial and a lot of those labels don't exist anymore, the ones that I would obsessively follow as a teen.

Nancy: Yes. I also lived in London. When I was at Nylon, I went to London Fashion Week all the time because we covered so much of that. It was great to write about, but wear? When London's buzzy, it's really buzzy, but it comes and goes.

Laura: I think it's why designers all over the world keep coming back to Claire McCardell, because her clothes are super wearable and they're pretty and people want to wear them. You see them and you're like, "I want that dress." Even now, you pick up a magazine or see it on Instagram and you're like, "Oh, I want that dress. I wish it wasn't from 1940.”

Nancy: It's also, I think you can imagine yourself in it more easily. There was actually a designer I quoted, who I didn't get to write very much about, although she's also very interesting, Jo Copeland. She said that "A French dress is so perfect in and of itself, it's hard to imagine a woman in it. When I design, I'm always thinking of how is she going to wear it?" She was talking about her own clothes, but that's Claire McCardell, very much so. You don't have that feeling of, "Oh, but where would I wear it? What if I spilled something on it?" It's more approachable and accessible many times.

Laura: Yes, it's more about the woman wearing the dress than the dress wearing the woman.

Nancy: Of course, the couturiers with their close clients who spent loads of money with them, they would collaborate on designs, but these women were leading lives that 99.9% of other women they just had nothing in common with them. They structured their lives around their fittings and dinner parties and balls and those kinds of thing. That's not reality for most people.

Laura: Returning to the book, you mentioned earlier that you knew about all these women separately, I knew about these women separately, but I think you did a really wonderful job of bringing together how all of their lives and careers were super interconnected.

Nancy: Looking into the Fashion Group International was great for that.1 I wish I could have spent more time in that archive. They all went to these meetings every month. They still have these meetings. I've been to a few of them. It's not what it was but they saw each other every month at least. I'm sure they saw each other socially.

Yes, I think that that was the most fun part. I think connecting all of this was really interesting.

Previous newsletters of mine on some of these “Empresses”:

Vreeland's Musings I

Annie Leibovitz’s photo of a broadly smiling Diana Ross stares out from the cover with “DIANA” overlaid large twice: “DIANA (Ross) Reflections by O’Connell Driscoll” and “A Question of Style DIANA (Vreeland) By Lally Weymouth.” Two legendary Diana’s, mononymous stars whose work and lives transcended their original industries.

Vreeland's Musings II

Following on from these earlier newsletters (“A Question of Style” and “Vreeland's Musings I”), here is more from Lally Weymouth’s interview with Diana Vreeland, published in Rolling Stone, August 11, 1977. This week centers on the 1930s in London, celebrity friends, Coco Chanel, and Vreeland’s time at

Vreeland's Musings III

As yesterday was the 119th anniversary of her birth, here is the final part of Diana Vreeland’s 1977 Rolling Stone interview. Previous sections can be read here: “A Question of Style,” “Vreeland’s Musings I” and “Vreeland’s Musings II.”

A Manifesto for Dressing

In her foreword to Marisa Berenson’s 1984 advice book, Dressing Up: How to Look and Feel Absolutely Perfect for Any Social Occasion, Diana Vreeland lays out as close to her manifesto on dressing that I’ve ever seen in her writing. She succinctly states her beliefs on the reasons why one should dress up with a quick explanation of the basics of how.

Elizabeth Hawes on Pregnancy Fashion, 1938

One of America’s greatest fashion thinkers (and designers), Elizabeth Hawes, turned her sharp mind to the question of maternity clothes during her own pregnancy in 1938. Months after publishing her first book, Fashion Is Spinach—one of the finest (and wittiest) critiques of the fashion industry ever written—Hawes wrote an essay for the June 15th issue of

To learn more about the Fashion Group International, listen to my interview with fashion journalist Marylou Luther.

Another fabulous interview and book to add to my list, thank you!!

Funny to think Bill Blass was embarrassed at one point to work in fashion, he certainly is one of my favorites in the 80’s episodes of Style, CNN. No one talks like that anymore about clothes, kind of a lost art sadly.

Fabulous interview. Glad to see Jo Copeland name-checked. Now there’s an obscure (now) designer but when you look through the old magazines there were always lots of ads featuring her clothes. Thank you!