When you hear “gay restaurant,” what do you think of? Somewhere in the gay part of town—San Francisco’s Castro, NYC’s Chelsea—hung with Pride flags? A drag brunch? Or something more subtle, an energy maybe? Erik Piepenburg’s new book, Dining Out: First Dates, Defiant Nights, and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants, is the first book to investigate the emergence and history of gay restaurants in America.

For Piepenburg, as he explains in our interview below, gay restaurants aren’t defined by gay chefs but by the clientele. Any restaurant can be “gayed,” and there can be a temporal quality to this gayness. These restaurants act as community hubs and sanctuaries; a place to escape homophobia, gossip with friends, fully exist as one’s true self; a venue for first dates and the morning after, for long brunches and after-club hangs.

As a journalist, Piepenburg writes this almost as a travelogue, crisscrossing the nation, visiting gay restaurants that highlight the wide variety of institutions that feed the LGBTQ+ community. His travels aren’t just spatial, but also temporal; he chronicles the history of gay restaurants from the 1850s to today, from the notorious (the Mattachine Society’s Sip-In at Julius) to the mythological (the Cooper Do-Nut’s riot).

Part of a small flurry of publications discussing the LGBTQ+ community and eating, this book forms a great pair with What is Queer Food? (read my interview with the author John Birdsall here.) These books provide very different pathways into the study of the gay experience with food; Dining Out through restaurants, where the gayness comes from the clientele and sometimes owners, with What is Queer Food? through chefs, who were “queering” food for an often-straight audience.

I spoke with Erik last month about his inspiration for writing Dining Out, how and where he found gay restaurants across America, and what he discovered about them during his travels. Dining Out is now available on Bookshop, Amazon, and wherever books are sold.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Laura McLaws Helms: To start, could you tell me a little about your background and what drew you to writing about the history of gay restaurants?

Erik Piepenburg: Sure. I should say I'm not a historian. I am not a food person. I have really never worked in the food industry other than a terrible week at Burger King when I was in high school. Those are the qualifications that I don't have. What I am, though, is a gay man. I've been a journalist for 25 years and have always just loved eating at gay restaurants. I came out and came of age in the '90s when gay restaurants were just everywhere in the gay neighborhoods that I lived in.

I'm just someone who loves eating with other gay people at restaurants and is curious about what happened with gay restaurants, at least in the numbers that I remember back in the '90s. All of that sparked a pitch that I sent to my editor in the food section of the New York Times in 2021, [an] article about what's up with gay restaurants. It turns out there's a lot that's happening with gay restaurants. The article I wrote for the Times came out four years ago. Then fast forward, and here we are with a book inspired by that article that takes a much broader, 100 years look at where gay people have been eating.

Laura: What did your journalism focus on before writing that New York Times article?

Erik: Mostly I've been writing for the culture section about theater, about film, about LGBTQ issues. I still do. I write a lot about horror movies specifically. That's a guilty pleasure of mine, but I've always been fascinated by gay placemaking, places like bars and, in this case, restaurants; other places where gay people have met one another for friendship, for romance, for entertainment, for all kinds of purposes. Even though people who look at my bylines in the Times will see recently a lot about horror movies, there's actually a lot of interest in LGBT topics as well.

Laura: How do you define a gay restaurant? Did you go into this book having a definition of an idea or did that idea evolve as you were doing your research?

Erik: If you ask me and other Gen Xers like me, "What is a gay restaurant?" and older gay folks to the Stonewall generation, I think a lot of us would sort of say, "Well, of course we know what that is. It's a restaurant where you walk in and there's mostly gay people." That's the definition that I went with because, unlike gay bars, which are understood to be gay spaces from the time you open your door to the time you're close and understood this is a gay bar for gay people, gay restaurants haven't really functioned that way all the time. Yes, there are some very gay restaurants; some of them that I mentioned in my book, like Annie's Steakhouse in DC is certainly a capital G gay restaurant. There's no mistaking that when you're in Annie's, you're in a gay restaurant.

There are other restaurants, including diners—and I have a chapter on diners in my book—where if you were to go there at let's say 8:00 AM or 9:00 AM, it might be more of a straight crowd, maybe people getting off of the overnight shift or parents who dropped their kids off at school and want to have coffee or something. Then you go there at 2:00 AM when the bars and the clubs let out and the whole room is just gay. Then you come back at 9:00 or 10:00 and then it's not as gay anymore. There's a temporal quality to restaurants that I think is interesting and sets restaurants apart from gay bars that I just think is an interesting differentiating characteristic that I'm fascinated by. Yes, it's not always a home run, “what is a gay restaurant?” For me, I know it when I see it.

Laura: I had never really thought of diners as gay restaurants. I grew up in London and New York. I grew up going to Cafeteria, which you mentioned, back in 2000 when it was a very different place. Before I read your book, I was like, "Okay, Cafeteria, Florent, Lucky Cheng's, these places that I've been, they hopefully will be covered," which they were. I hadn't really thought about diners as such a spot of gay dining, but it makes total sense as you lay it out.

Because [being gay] was illegal for so much of the past century, there are not that many archival materials, right? I was wondering how you even went about researching and finding out about much longer-ago gay restaurants.

Erik: I spent a lot of time traveling the country and going to archives, both gay specific archives and also more general archives just to see what was out there. Interestingly, I think one of the best resources that I had were newspapers, gay newspapers and not gay newspapers that were part of the entertainment section. What was fascinating is that when you looked at newspaper ads from the '20s and '30s, there were often ads for what back then were called female impersonator shows, which today we would call drag shows.

A lot of these venues that brought in female impersonator shows also served food. For me, anytime you mix that sort of gay culture—and I'm not totally sure that they would have called it gay culture back then, but certainly what we would call it today—when you mix that with a place that served food, as far as I'm concerned, that is a kind of a gay restaurant or at least an early example of what gay restaurants eventually became. Really, I just spent a lot of time looking at entertainment ads in newspapers to see where that might've taken place.

Another early example are automats, these grand palaces where you'd walk in and you'd put a coin in the slot and you'd open a door and get roast beef or you'd get pie or chocolate pudding or whatever it was. These were very popular in the '20s and '30s. There's a wonderful play that was on Broadway about 10 or so years ago called The Nance that was set during those times. The very first scene takes place at an automat. I used that play and the understanding of what was happening between these two men in this scene and thought to myself, well, of course, anytime you open the doors to this kind of a restaurant—and it was in New York, it was in Times Square, theater, Broadway people, a heavily gay community there—well, of course, gay men would find one another at automats.

I looked back at the historical record, in that case, in this wonderful play, to extrapolate and say, “well, yes, that was a kind of a gay space or it was a space that was queered,” as we would say today. They didn't have that language back then, but it was a space that was, at least to the eye, straight, unless you were gay and you knew how to find your people in the room. I thought that was just fascinating to try and understand what that must have been like.

Laura: That's another thing that I hadn't considered when I thought about Horn & Hardart. I'm sure you saw Lisa Hurwitz's documentary about the Automat. They're the perfect sort of cruising grounds because you can see who's there and then anyone can sit with each other just because it's cafeteria style. There's that sort of openness to meeting people that you wouldn't get in just a normal restaurant where people are sitting with waiter service. It's interesting to reevaluate all of these places that were not specifically gay, but obviously there was an undercurrent, right? They were used differently by gay people. They were queered by the way that they were used.

Were you able to find any letters and diaries of people talking about eating at any restaurants that were gay? That you were like, "Oh, okay, that's this person in historical time talking about a gay restaurant that they loved or something."

Erik: I wish I had found more letters, certainly from the '20s and '30s. I didn't find those; I'm sure they're out there. I would love to keep exploring those early decades of the century because I think they're certainly there. I did talk to many elders whose memories are more towards the '60s and memories of going out here in New York, for example.

I think what it goes to show you is that the scholarship on gay restaurants is still very fresh and needs to be discovered. I was shocked to learn that as I started researching this book is that there's never been a book about American gay restaurants. It's never been written before. There's been some great journalism about gay restaurants of the past, but I was shocked to learn that [there were no books]. I would love if there are other researchers or just curious journalists or academics who want to explore those early years, I have to imagine that there's some wonderful archival material out there from those early decades. I hope this book sparks more of that research.

Laura: It’s really interesting how little scholarship or writing at all, in general, how little there's been on gay food, queer food, gay restaurants, queer restaurants until recently, there's a burst of books and conferences and things like that currently. Why do you think that there's such a moment? John Birdsall’s book came out at the same time as yours. Then there's Queers at the Table, an anthology, coming out in a few months. There was the Queer Food Conference. Why do you think there's a sudden burst of writing and work around it?

Erik: My book is focused on restaurants, really. I don't really focus on queer food or queer chefs. John's book is just fantastic in exploring “what is queer food?” I think that's just a great angle to take.

I really wasn't looking to talk about food, but I will say in terms of why this is happening for restaurants, I think because how people eat out, not just gay people, has changed so much in terms of apps or COVID, has upended the industry in so many ways. I think as gay neighborhoods are disappearing in a lot of ways, and those used to be the anchors for lots and lots of gay restaurants, I think there's a thirst for people to understand those types of spaces or restaurants before they disappear. At least, for my generation, certainly, I wanted these restaurants to never be forgotten. I think there are other people of my generation and older, certainly, who want to understand and honor these restaurants before the idea of what a gay restaurant is disappears even further.

I was at a party recently with mostly Gen Z and millennial gay men; I was by far the oldest person in the room. This conversation started about, "We'd love a third space that's not a bar… where else can we go to be together?" One person said, "Well, it'd be great to have a gay cafe where you could just sit there and maybe meet people and there were books there." I chimed in. I said, "Yes, we used to have those. Those were everywhere. Now they have gone because of how gay culture has shifted online."

I think there's a real thirst for younger generations to have those kinds of spaces. I think as younger generations maybe look to gay restaurants or gay cafes as possible meeting places, I think that's also going to bring up interest in the past when those kinds of places were everywhere, at least in gay neighborhoods and also in small towns and medium sized cities as well.

Laura: How did you go about finding some of the small-town ones that you visited? I know Green Bay is not a small town, but [gay restaurants] that are outside of Chelsea or the Castro, these famous gay areas. How did you go about finding those ones that you visited?

Erik: I was really very interested in not focusing on the coasts too much because if there's a hot gay restaurant in Miami, I'm like, “Fine, whatever. That's a dime a dozen.” I was so interested in going to other parts of the country. This is just, I guess, how I work as a journalist. I think I Googled “LGBT restaurants Wisconsin” and just looked at what came up. I think one of the first results was Napalese Lounge and Grille, which I write about in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Yes, it's in Green Bay, which is not a small town, but it attracts people from all over the region who are from small towns. I thought, "Well, this is just a fascinating place that I have to write about and I have to get to." I'm so glad that I did, because I think that's one part of the book that really underscores how gay restaurants are not just an urban thing. They're not just a coastal gay neighborhood thing. That you really have this thriving safe space in Green Bay of all places that serves people who have nowhere else to go to live as their full trans selves. I think that's one of my favorite chapters, really, to have been there and seen what that small little bar with cheese curds on a very quiet block in this very quiet neighborhood is really changing lives.

Laura: I don't think you mentioned any, but did you hear of any in areas which are much more conservative? Underground restaurants in say small towns in the South. Did you hear of anything like that? Is there a world for those people who need it?

Erik: Yes, a lot of places in small towns or in the South or conservative areas, it may be the local Denny's that is welcoming of everyone. That's just where you can go, because as long as you don't cause problems and you pay your bill, just like any other customer, they'll let you be there with your gay friends.

I think that's certainly the case at Waffle House in the South, those types of diners where you can be yourself in some ways. Does it mean that it's not still dangerous once you leave that place? Absolutely not. I think diners have for a very long time served that purpose of open to everyone and generally affordable. It's not just for people who have lots of money to spend. Those places are absolutely in the South and in Ohio, where I'm from. Certainly, that's the case.

I would also point to Florida, which has gotten very conservative now. Then you go to Wilton Manors, Fort Lauderdale, and that is a little bit of a bubble, a gay bubble in the middle of Florida. To think that that is a draw for people from Florida and other parts of the country, and those restaurants are just mom-and-pop type restaurants that have become these safe spaces in this otherwise conservative environment.

Laura: Since writing this book and waiting for it to come out, how have your thoughts about the current state of gay restaurants changed or evolved? Where do you think we are now?

Erik: I think we're actually in a really good place, because we're headed in two directions. I talk about this in the last chapter—we have older generations of gay people in Fort Lauderdale, I would also say Palm Springs, which is a little bit of a wealthier community, but you have older gay people who want to live in all gay environments, as they did back in the '70s and '80s. They want that experience, and they're getting it. If you walk down Wilton Drive in Wilton Manors, it's just gay, gay, gay, gay, gay all day. That's by design, and that's what that community wants. Again, those are Gen X and older.

Then on the other hand, we have what I call in the book “the queer vanguard of queer restaurants,” which are far more interested in queer identities, in transness, in non-binary people. Sometimes the food reflects that, and the dining room reflects that. There's a restaurant in New York called HAGS, which is a very fine dining restaurant. On the table, or maybe at the front, there were bowls with little pins with pronouns on them. You could choose the pin that you wanted, and you could wear the pin with the pronoun that you wanted to use. I just thought, "Well, that never would have happened in the '90s." These queer restaurants of today are far more invested in queerness, are far more invested in social justice issues and political issues in ways that older restaurants weren’t. It sort of depends on your age, there's a gay restaurant for you. Certainly, there's crossover between the two. I think we're in a real solid place with gay restaurants, no matter what age you are, and no matter how you identify under the LGBTQ umbrella.

Laura: I know you talk about this a little bit in the first chapter, but why did you choose to use gay versus using queer or LGBTQ? What was your decision-making process?

Erik: Honestly, gay is just my Gen X shorthand for LGBTQI, which as a journalist, LGBTQIA+ is just a mouthful and gay is just my Gen X way of shortening it. I don't use the word queer for me. Maybe it's just a generational thing. I don't consider myself queer. As a journalist, it really comes in handy because queer is just everybody. I do use that throughout the book in places as a shorthand. Gay is just a shorthand. In terms of the book, to call a space in the '20s queer is ahistorical. You would never call it that. In terms of my book, I tried very hard to use the language that would have been used at the time.

Laura: I know that this book just focuses on America, but I was wondering if during your research, anything came up about other countries. Do gay restaurants in other countries operate in the same way that they do in America?

Erik: I actually don't. It's interesting. A lot of people have asked me what about restaurants in Europe or South America, and I really didn't [research them]. I very much focused on the US. I have to imagine that there are certainly rich histories of gay restaurants in other parts of the world. I'm specifically curious about restaurants in maybe more conservative parts of the world. If someone wants to write that book, I would read the heck out of that. I'm afraid I was very focused on the on the US here, though.

Laura: You're American, it makes sense. Having the ability to crisscross the country, which it seems you did from visiting all these places in person, you really get a sense of the vastness of America and the vast variety of places and types of restaurants and institutions still going today. I never expected that the largest bathhouse in America would be in Cleveland [Flex], and that it would have this wonderful man cooking food there for people who don't have families. I thought that was a really heartwarming but also heartbreaking story at the same time, that they don't have families to go home to for the holidays, so he cooks for them.

Erik: The section on Flex, like you said, that's exactly right—it's heartbreaking and heartwarming at the same time. Flex is not a gay restaurant at all, but it serves a gay restaurant purpose. For these older men—I think he was 90 years old in the book—he has nowhere else to go. That broke my heart as I wrote about that, but it serves the gay restaurant purpose of welcoming people who have nowhere else to go over a meal, which I just think is so special. The fact that it's in this weirdly sexual environment is just a testament to gay resilience somehow, too. Here you're having ravioli and a warm roll and you're talking with people, and over here there's a jacuzzi and a gay play space. It's just fascinating juxtaposition of gay worlds coming together in one place.

Laura: There are quite a few times when you're talking about a place, and you mention sex and you bring up the food and sex together. I guess, at least in your eyes, as a gay man, do you think that they're inextricably linked? Food and sex.

Erik: Yes, I think in some ways, when you think that at bathhouses would have their real big heyday, at least in the US in the '70s and '80s, there was food. You could spend the whole weekend there and there were meals served and there were menus there. That's just part of gay men's culture, I think, in a lot of ways. I think that's lessened as bathhouses have changed; I think you don't really find those types of restaurant spaces in bathhouses quite the way that they were.

Gay and lesbian bars have for many, many decades served food. Those aren't exactly sex spaces, but they're flirtatious. Not so much here in New York, which is interesting, but in other parts of the country, gay bars are where you would go to have a drink and you'd get a burger, which I think is just an example of a sexual space that also has food in it.

That's not necessarily a gay thing. There's certainly straight bars that have booze and food, but I just love that in other parts of the country… Food, flirtation, drinks, dancing, it's all just part of the mix. Man, I wish someone would open up a place like that here in New York, because I think it would be a big hit.

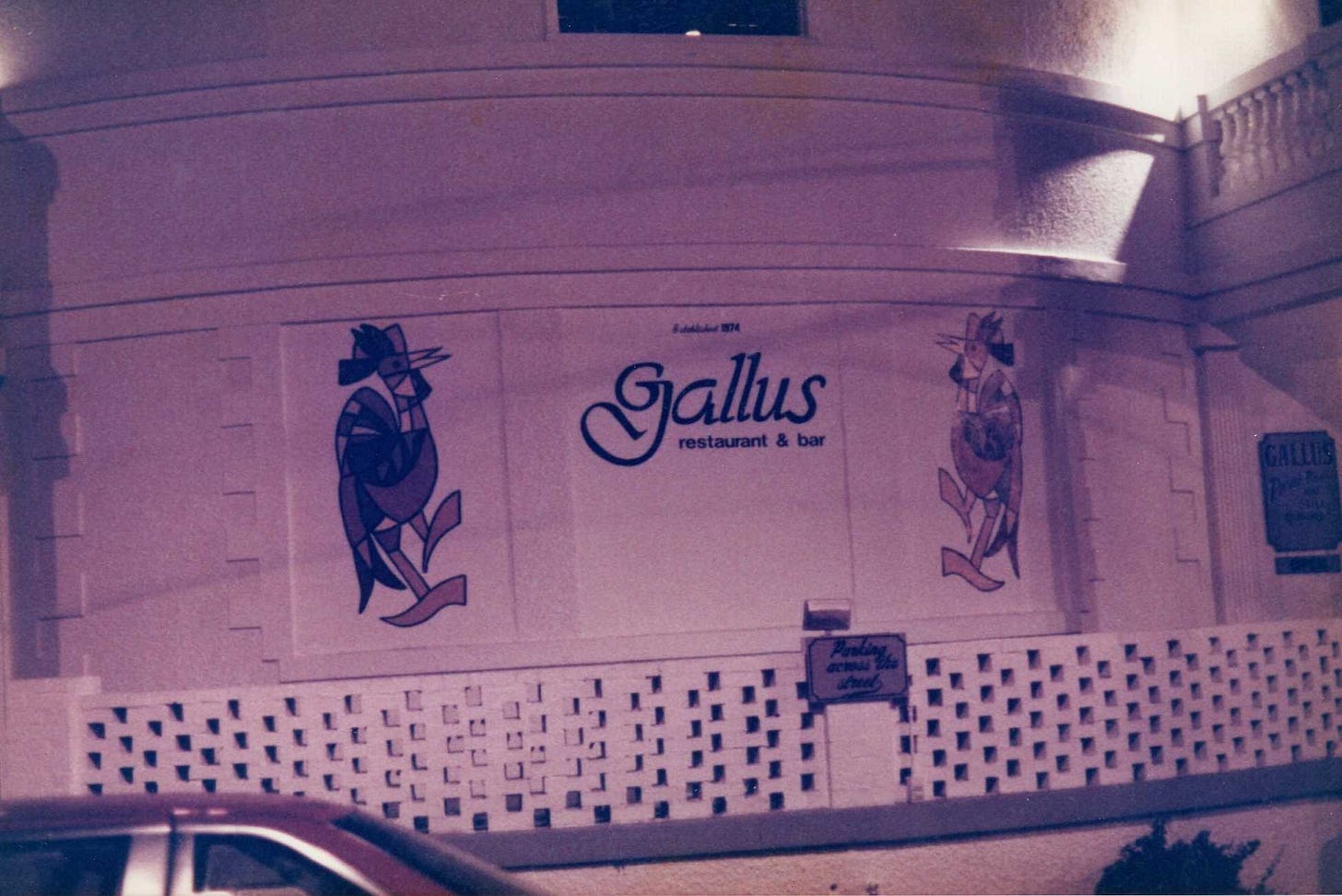

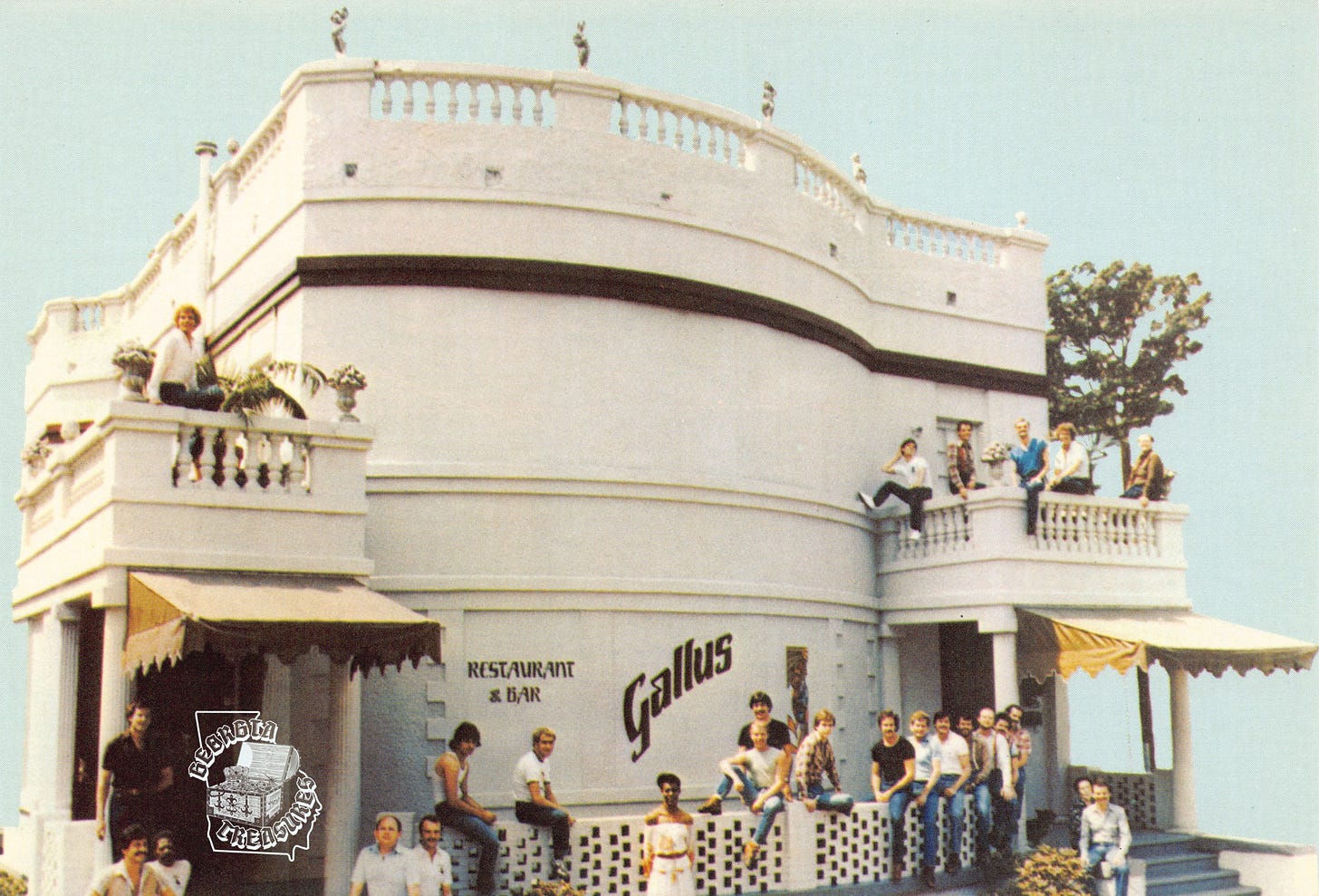

Laura: You mentioned that if you could go back in time, and go to any of these restaurants, it would be the Gallus in Atlanta. That definitely sounded like a really amazing place, that had all of these different places on all of these different floors. I think you called it a gay department store.

It's unfortunate that there's not more pictures of it online. I was trying to get an idea of what it looked like inside and couldn't find any, but it sounded like a quite amazing place where you could have this whole buffet of experiences.

Erik: Yes. [laughs] It was a buffet. That's absolutely right. There aren't a lot of places quite like that anymore. What was interesting about Gallus is that it did have fine dining aspirations. The dining room was white tablecloths and there were flowers on the table and the servers had white shirts, but then you go downstairs and it is hustlers. It was, again, this combination of two gay worlds.

There is a wonderful video that I mentioned in the book that does take a little tour through Gallus and so you can see the dining room. We don't see the hustlers but you certainly see the servers and some of the bartenders and it's very '80s and it's just wonderful.

Laura: Was there anything really surprising that you uncovered while you were researching or writing?

Erik: I think what surprised me was just how long gay people have been going to restaurants. I make the argument in the book that, to me, under my definition of a gay restaurant, gay restaurants have a much longer history than gay bars, which again, gay bars generally have been for gay people during business hours, whereas gay restaurants have this temporal quality to them.

If you think about it, the automat predates gay bars, really, the way that we know them in the US. I was surprised to have an understanding of, "Oh yes, gay people have been going out in public to meet each other since the beginning of this country," and gay restaurants have of course been part of that experience.

You mentioned Florent. You've been to Florent and Lucky Cheng's? Lucky Cheng's is still going. It's a legacy gay restaurant.

Laura: Yes, I had no idea that it was still going. Because once I saw that it closed on First Avenue, I had no idea that they moved up to Times Square.

Erik: I wouldn't say it's that gay anymore. They really only do drag brunch, which is fantastic. Good for Lucky Cheng's, they're wonderful. The dining room has certainly changed from the first year that they were open, which was a very different dining room. I'm just so glad that Lucky Cheng's is still doing their thing. Tora Dress, one of the queens who I talk to in my book, is still there and still doing her thing. I'm so happy that Lucky Cheng's is still around even though they look nothing like what they did when they started. Drag queens are still getting work. I support that 100%.

Laura: What are you working on now?

Erik: Right now, I'm actually focusing more on my New York Times horror movie stories that I'm working on.

Laura: What's your favorite horror movie?

Erik: Oh, that's a great question. It's hard to go wrong with the original Halloween. It's just such a great example of a slasher film. Jamie Lee Curtis is fantastic. The monster in the movie is so terrifying still. I would say it's hard to go wrong with that.

What is Queer Food? A Conversation with John Birdsall

How do you define “queer food”? This is the question food writer John Birdsall contemplates in his new book, What is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution (W. Norton), which was released earlier this week. Mapping a large cast of characters over the course of a century, Birdsall weaves in and out of their stories, in and out of the closet, charting a w…

Culinary Nostalgia and 'The Underground Gourmet Cookbook'

We all have those restaurants—those venues that, just thought of them, brings us back to a certain place and time in our lives. Maybe they are from childhood, possibly young adulthood; maybe they are still going, possibly long closed. Where you can be walking down a street half the world away and the sight of a chair through a café window can trigger a …