Claire McCardell: The Designer Who Set Women Free

A Conversation with Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson on her New Book

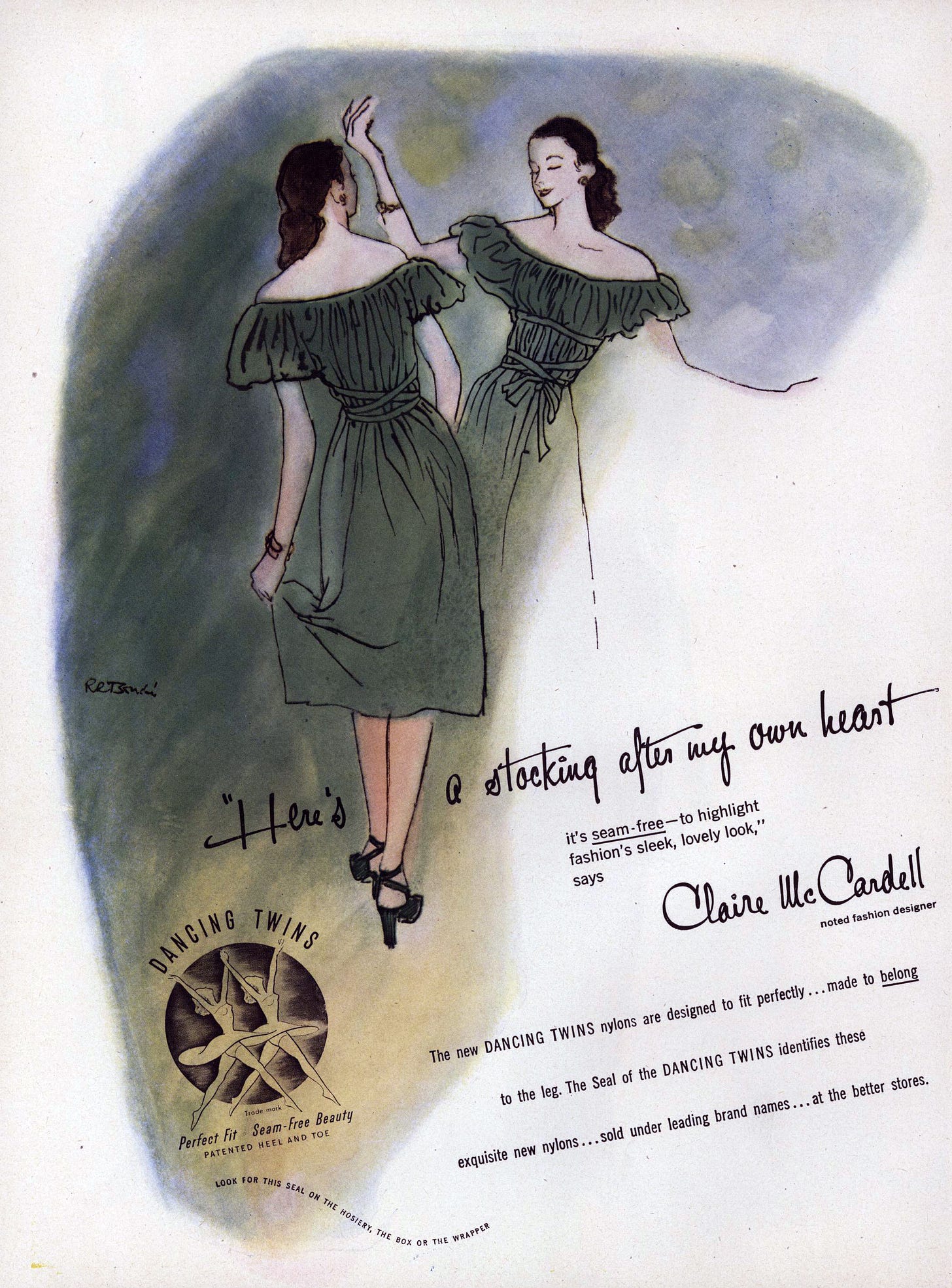

What makes a piece of clothing “modern”? There are likely more possible answers to that question than I could possibly ever get to here, but somewhere amongst them would be words like “clean,” “ease,” and “movement.” For almost a century, there has been an overwhelming consensus in the fashion world that Claire McCardell’s designs were and are modern. In 1944, Bernard Rudofsky wrote of McCardell in the essay for his famous MoMA exhibition, Are Clothes Modern? [link to download a PDF], “True inventiveness in design is practically restricted to play-clothes, a category of dress which, in time, may become the starting-point for the creation of a genuine contemporary apparel”—and it is true that all that feels modern and fresh since then feels very much to be a descendent of her 1930s, 40s, and 50s designs.

But, who was Claire McCardell? For the first time, author Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson delves into the full story of Claire. Whereas earlier books have focused more on her designs, Claire McCardell: The Designer Who Set Women Free seeks to cover every aspect of her life, from friendships to romance, childhood to stepchildren—and, of course, business and design.

As a biographer, Dickinson did the heavy work of tracking down still surviving family members and uncovering unseen archives, sifting through everything to develop and write an immensely readable look at this beloved yet underappreciated designer. I love Claire’s designs and I wouldn’t be surprised if, since you’re reading this newsletter, that you do too, but outside of the fashion and fashion history worlds, her name and significance are too little known. Hopefully this book—which also brings in important topics like women’s work, rights, and entrepreneurship—will help bring her name back into the larger conversation. As Elizabeth says at the end of our interview below, “She spent her whole life fighting to get her name on her label. She was one of the first in ready-to-wear to have that happen. It felt really important to me to give her name back… That's why the book is her name.”

Below is my far-reaching and comprehensive conversation with Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson. We spoke about everything Claire, how she came to write this book, her background, being a working woman (both in Claire’s time and today), the appeal of McCardell’s designs, the research and writing process as a working mom, and so much more.

If you are in NYC this week, Elizabeth will be discussing Claire and her book at The New York Historical Thursday night, June 12, 6 – 7 pm, as a live recording of the podcast Articles of Interest with host Avery Trufelman. Advanced copies of the book, Claire McCardell: The Designer Who Set Women Free will be available for purchase exclusively at The New York Historical prior to the program. Purchase tickets for the program here. If you go, check out the Claire McCardell “Pop-over” dress that is currently on view!

Claire McCardell: The Designer Who Set Women Free is to be released June 17; you can preorder on Bookshop, Amazon, and wherever books are sold.

Laura McLaws Helms: Thank you so much for agreeing to talk with me, and having the book sent. I really enjoyed it. Why did you decide to write about Claire McCardell? What is your background?

Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson: I began my writing career really writing about architecture, design, and urbanism. I think that I've always been really interested in the human-made and design. I haven't necessarily been a fashion historian or a fashion person, but I entered the story of Claire through a dress.

I was really interested a few years ago in this 1938 dress that she made called

the Monastic, which I write about in the book. It was this before and after moment in fashion, where design really started to move away from that corseted and structured fashion of Paris and of the past, and move into what now we understand as sportswear. What interested me about Claire wasn't just that she was inventing these or designing these really interesting new types of clothes, but why she was doing it, that she was really doing it at a time when women were starting to have careers, to live in New York, and what it meant to dress for that autonomy and independence. I was very curious about who she was and how she did that. That's what led me into the story.

Laura: How did you first get introduced to her work?

Elizabeth: I find that, if you're in the fashion world, people know her, because she's understood to be this progenitor of American fashion. For me, it was because I saw an exhibition of her work. She has an archive here in Maryland, where she was born, at a place called the Maryland Center for History and Culture. They put on an exhibition with the Fashion Institute of Technology several decades ago [''Claire McCardell: Forging an American Style'' at the Maryland Historical Society, "'Claire McCardell and the American Look” at MFIT]. I was young and impressionable, and I saw her clothes, and I never forgot them. I really think that it was thanks to her archives and to some curious curators at the time who revisited her work that first introduced me to her.

Laura: Yes, I think that [exhibition and associated book, Claire McCardell: Redefining Modernism] really did redefine modernism and put her within a larger canon, which connects with your original writing and architecture, like this canon of American modernism. Not just modernism in architecture, and design, and art, but also in fashion.

Elizabeth: Yes, and it was such an extraordinary time. There are those moments where you're like, "Oh, if I could transport myself back to a place in time…” I think being 1930s, 1940s New York, as MoMA is being created by women, that the Ninth Street women were starting to do abstract expressionism. You had this birth of not only that modern sensibility in architecture and design, but also in clothing and industrial design. It was just such a really interesting moment in design history in America, and the world.

Laura: It's definitely one of the periods I keep coming back to. When you decided to start looking into Claire, did you know that you wanted to do a biography, or how did you come to decide to work on her and make this project?

Elizabeth: That's a great question. I started small. In 2018, I did a piece on Claire McCardell for the Washington Post Magazine. That really left me with a lot of questions. As a writer, I find when I have a lot of questions, that's when I want to keep going. I think one of the things that I really was interested in, because what Redefining Modernism, the book, did was really put her into this context of why she was modern, and what was so unique about her clothes and her process.

I still wanted to know about her private life. I wanted to understand how a woman from a rural small town in Maryland became, effectively, one of the most influential designers in the country, and how she did that at a time when a woman couldn't have her own bank account. She was doing things at a time when women were still being arrested for wearing pants in public. I think that there was this desire in me to, as a woman, want to know how she did it. Also, because I really sensed that many of the things that McCardell did in her design of clothes, and the way she wanted to give women freedom and movement in their lives, we're in a moment now where those same forces are clapping back on us again, that, unfortunately, as I researched Claire's life, I was seeing a lot of similarities in what's happening right now for women.

There's that moment in the book where I write about her being in conversation with Betty Friedan, and it's the 1950s, and it really is this McCardell versus Dior moment, where the 1950s had this message of what we're hearing now—this trad wife, proto-national idea of be a good housewife, wear a pretty dress, and be in the kitchen, and have babies. Claire was very much, her designs and what she was doing, were very much antithetical to that. She wanted women to live autonomous lives and be able to choose how they wanted to live. You can see how that plays out very much in clothes and fashion.

Laura: Do you think she would have considered herself a feminist?

Elizabeth: Someone asked me that, and it's interesting. I don't think the word feminist was used as much in the '30s and '40s. I don't think that they saw it. I don't think Claire necessarily would have seen it as “I'm joining this movement to advance the rights of women.” I think she just believed that women deserved it, and were ready for it, and that it just seemed matter of course to her.

I think, looking back, absolutely she's a feminist. I think at that moment, Claire and the women in New York fashion at that time really just saw themselves as doing it—believing that they had a right to be at the table and believing that they had a right to build these businesses. It's interesting to me to see the ways in which she subtly and explicitly worked her way around gender limitations to just get it done.

Laura: When you decided to start looking into finding more about her private life, how did you start approaching the research? Because I know there's so much out about her work, but there's not as much about her private life at all, prior to this.

Elizabeth: She was very private. There's also this part of me that had this conversation with myself as a writer about, when someone's expressly private in their life, in their lifetime, how fair of it is for me to go and dig in and try and make that public? I felt like it was important to understand that tension that she was living in, between being a woman of business and being a woman with the requirements of American society.

I was lucky enough that her family donated her personal letters to an archive here in Baltimore where I live. I spent a ton of time going through that archive. I spent a ton of time going through her archive at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York. I read every single letter, and I transcribed every single letter, and I learned to read her cursive. Each letter required me to go on this other rabbit hole of research, because names were mentioned, or events in history were mentioned.

I'm also lucky that her niece and nephews and relatives are still alive. Unfortunately, the generation that really knew her personally is not, but I had people that had connection with her who could tell me what they remembered and show me new work. I went and visited her nephew down in South Carolina and was able to sit at the kitchen table and read through even more letters and more notes.

I also was able to share with them, "Here's what I'm thinking. Do you think I'm on the right track? Does this make sense to what you know of the family history and story?" They were very generous with their time. Ditto with Claire's husband's family, I was able to interview the granddaughter of Irving Drought Harris. She really was very generous in helping me to understand that family and get a better sense that what I was understanding of that marriage was fair.

Laura: Coming from a place where I felt like I knew probably more about Claire than most people, I knew nothing about that whole side of her life with her husband, and particularly the children, and the way that she interacted as a stepmom. It does really illuminate this whole other side of her personality that you wouldn't have any knowledge of otherwise.

Elizabeth: It was interesting, because she didn't want to have children. She never expressly wrote that anywhere, but I think, after doing enough research and talking to enough people, I can say she didn't set out in life to be a mother, but when she became a stepmother, she had this respect for those children. I don't know that she was the cuddly mom type, but I think she was someone who was deeply kind, very thoughtful, and really respected them as human beings, in a way that subsequent generations recognized as being really important to John and Liz, the two stepchildren.

Laura: It's fascinating learning about all of that. Was there anything else that you discovered that was surprising, or that felt like it opened up a new understanding of her and her work?

Elizabeth: I think that one thing for me that helped me understand her work was really understanding fashion history. That was one avenue to better understanding the ways in which clothes have been used over time to either control or free individuals. The fact that we're still living with that today. I have a 13-year-old—dress codes for young women in schools are still a thing and still very gendered.

We're still having a lot of debates about what is clothing, who's allowed to wear what. I think one of the things that really resonated with me is that Claire realized, “Why are we gendering fabrics? Why are we gendering pockets?” I think of that lovely RuPaul quote, which is, "We're all born naked. The rest is just drag," right? That was one thing that was really interesting to me.

I think the other thing that was really illuminating was understanding her friendships with other women and the fact that Claire was not perfect. She had a moment where she had a fallout with her dear friend, Mildred Orrick. You can read in the book, of course, about what happened with the leotard, and the way she became known as being the one who originated that idea when, in fact, it was her friend, Mildred Orrick, who originated that idea. I didn't want to write a biography that was just, “Isn't she wonderful?” I wanted to explore the truth of the complexity with female friendship and business, and how you support each other, and how sometimes even someone with the best intentions makes missteps. You see a little bit of that depth, I think, in that story with Mildred.

A dress designed by Mildred Orrick:

Laura: How do you think her childhood in Maryland affected her work and how she designed?

Elizabeth: I think she was lucky in two ways. One, she had parents, particularly her mother, who believed that a woman in that era was allowed to make big swings. They both, her parents, wanted her to be college-educated, which wasn't the norm. She certainly had to fight for the ability to go to New York. They were nervous about that, but they supported her, ultimately. At the time, there were not a lot of parents who would have gone out on that limb and let their young daughter go to New York on her own.

I think the other thing is Frederick, where she grew up, is a very pragmatic town that has a robust history of manufacturing. She witnessed these 19th-century mills making textiles and making stockings. She grew up around women who made their own clothes. She grew up with an entrepreneurial family where she saw in her grandfather who owned a candy factory—he designed his own molds, he made the candies and he sold them. I think she saw, in her lifetime, not only entrepreneurialism, but this idea that you can design something in your mind, you can make it, you can sell it.

Frederick, obviously, is rightfully proud that she is a daughter of Frederick. I think that is one of those Maryland towns, as I write in the book, it was rural, but it wasn't remote. Actually, a lot of people came through there. When I was doing research on what her childhood was like, I'm seeing that, at the local opera, there were suffragists coming and talking about the right to vote. There were ideas, and art, and theater. I think that's the other thing she was exposed to. Her parents took her to see plays in DC. They exposed her to museums. So, she had a reverence for art and design early.

Laura: Yes, and it's remarkable what you were saying about them letting her go to New York. They also let her go to Paris, right? If you're going to talk about a place to go back in time to, that would be a good one, too.

Elizabeth: Right? How fun would that be, to go to those [haute couture] sample sales at the end of the year? The other thing that's so interesting to consider about McCardell is she understood the biggest challenge of ready-to-wear was fit, because when you go to Paris and you get haute couture, or you go to Hattie Carnegie, who was New York's version of haute couture, you got everything fit to your body pristinely and with every stitch in place.

One of the things Claire was so brilliant about doing was creating dresses that could be fitted to a body with a belt, or spaghetti ties, or other ways to make something fit that didn't require it to be sewn onto your body. I don't want to graft a 2025 version of body positivity on that era, because, of course, we're still talking about clothing that, certainly, benefited mostly women of a certain size. I think McCardell was among the earlier designers to think about how do we think about fit for different body sizes and different body types?

Laura: Do you have any of her clothes? Have you ever worn any of them?

Elizabeth: Sadly, no. I wish. How about you? Do you have any McCardell’s?

Laura: I have two dresses, but they're not in perfect condition or anything, which is fine, because then you don't feel so bad about wearing them. I was going to ask if you had any lived experience, embodied experience of the clothes, because I think, especially if we compare them to how other dresses from that era feel on the body, it's a totally different experience, because there isn't the need for girdles. If we're talking about the later '40s after the war, but even during the war years, the clothes are controlled, and require a sculpted body, compacted, and perfected into a shape, and it's a very different experience wearing them.

Elizabeth: In the book, I have this amazing photo from a British Pathé ad or newsreel about fitting into a Dior New Look dress in 1947. There's this photo that I have of the woman helping the other woman tighten into that corset. She's got this impossibly thin wasp waist. The other woman's having to pin on all of the shoulder pads and the hip pads. Again, it's that idea that you needed two people to get dressed. You couldn't get dressed on your own because you had to shape your body into this very idealized form.

While she certainly had dresses with zippered waists that wouldn't fit everybody, the Popover had a button system that you could adjust the buttons, and that was so radical. We take it for granted today, of course. People who aren't fashion historians and vintage enthusiasts, and don't have your kind of level of knowledge, don't appreciate that this was a big deal to say you can wear a dress without a bra, without any girdle.

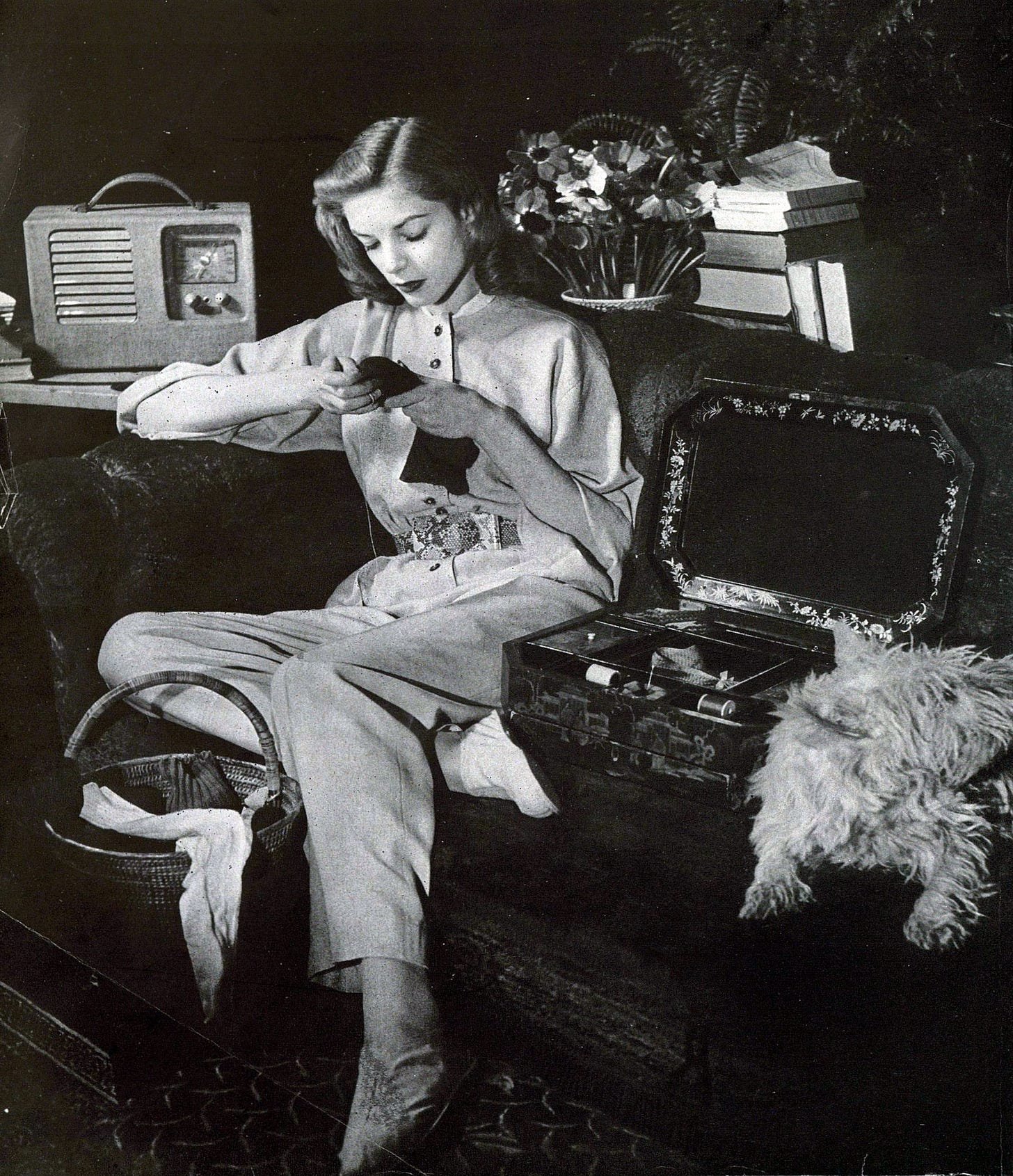

There was one set of photos I wish I could have gotten the rights to, where you can see in those images, you can see nipples, you can see boobs, you can see the outline of a breast. The idea was not to be overly provocative. It was just like, “so what?” The idea that a woman has a breast, and Claire was very against even the push-up bras. She's like, "Oh my God, we're putting all the emphasis in the wrong place," is what she said. I love to see how even in the time there were some thoughtful photographers who understood you don't need to truss a woman up to wear a McCardell. She can just wear it.

I think embodied is a great word that you used. What is our embodied experience as we move through the world? We've all been in that moment where we've felt [we are] in the wrong clothing, and we feel self-conscious, and we feel it on our skin, and we're constantly tugging and pulling. McCardell once said that comfort is really the pinnacle of style, because if you're comfortable, you're confident and you feel great in the world. I always think about that now. I think she really had this excellent message of “find your own style, don't follow fashion.” I think that's something I certainly still need to hear and remind myself of.

Laura: It's interesting how the photos, there's so many amazing photos of her clothes, but I feel like the photos that really capture the clothes, and the ease, and comfort, and the beauty of them, are taken usually by female photographers, like Louise Dahl-Wolfe or Toni Frissell. The female photographers look at them and understand that, even if they're not personally wearing them, they know that there is something really womanly in a way that is more natural, I think, more naturally womanly than the constructed “womanly” curves of say a Dior.

Elizabeth: I absolutely agree with you. That's one of the other reasons I wanted to write this book. There's a great book that came out last year by Nancy MacDonell called Empresses of Seventh Avenue—she has a chapter on Claire, but she also goes into Louise Dahl-Wolfe and Dorothy Shaver, people I talk about a bit in my book, because this was such an extraordinary time of women really celebrating one another.

Georgia O'Keeffe loved to wear McCardell's clothes because she could go rafting in them, and she could paint in them, and she could collect rocks in the pockets. There's this empowerment of women moving through the world, being creative and being creators. Louise Dahl-Wolfe knew how to put women in motion, and she knew how to put them in the environment.

One of my favorite photos, which is in the book, is of an amazing plaid playsuit with this romper bottom that McCardell designed, and Louise and Diana Vreeland went to Arizona and they juxtapose that against a Frank Lloyd Wright building. That says it all to me, right? It's a woman powerful in the landscape juxtaposed against this other powerful designer. I love that she's forefronted. The woman gets the scene, and the Frank Lloyd Wright is the background. It really is that idea of, yes, a woman being in power in the world.

Laura: How did you balance researching and writing this, teaching, and raising a daughter?

Elizabeth: It's a great question because I honestly thought about Claire a lot when I was looking at her day planners, because she was working, she had stepchildren, she had all these events, she was a critic at Parsons. For me, a couple of things—I have a partner, I have a husband, who believes in a shared marriage. We truly are partners. I, luckily, did not have the marriage that Claire McCardell had, which is that she had a very traditional husband.

I benefited greatly from having a family dynamic where both my daughter and my husband understood that my time and my writing were important and they made space for it. Probably one of the greatest moments in the writing of this book was finding a little note on my desk one day where my daughter had written, “I'm really proud of you.” It was like modeling the importance of doing what matters to you in context of your family.

I think that question leads me to another reason I wanted to write this book, is that I think we tend to, in this culture, prioritize a productivity model of business that feels very male-driven. We tend to prioritize a very male top-down approach. If you realize that what happened in the mid-century with fashion is it was built on women, their version of entrepreneurship, their support of one another, their creation of networking groups, and checking in with one another, it was women who did it.

The truth is, is that we just don't know the story as much of female entrepreneurship, and the ways in which that, actually, does extraordinary work in the world, to build the things that we have now. It seems so ironic. One question I get is, how would Claire think about fashion today? I think she would be shocked that so few women run their own companies, or that so few women are at the head of design firms because that's all it was back then. Yes, men mostly owned the manufacturing arms, but it was really a women-led enterprise that built American fashion. I'm interested, honestly, in knowing how to lead my life that way, and rejecting the lean-in, hardcore way that we're told we're supposed to be in business and doing it this way, instead.

Laura: This is something that I'm desperately trying to figure out now that I'm taking care of a baby most of my time. It's a hard thing to figure out and balance and to try develop a new way of working, as you're saying, even if it's referencing the past.

Elizabeth: I think too, I realized that balance is such a bullshit word sometimes for us, because it's never balanced. The year of writing this book was intense. I spent two years on the book, researching and writing it. I wrote it in a year, and the last year has just been like editing and all the other business of publishing. It's been unbalanced. It really has been. I think the hard part is now, how do I transition into trying to get back into a routine?

One of the things I loved about McCardell is she lived a very unbalanced life because it was seasonal with the fashion, but she understood that she could take that break. She vacationed a lot. She went away a lot. I think that's what we've lost right now in this grind and hustle culture, is they worked really hard and singularly focused, but then there was a break.

Now we live at a time where there is no break. I think for me, I'm having to redefine what productivity and success looks like. Some of it is also recognizing that having a home I like, spending time with my kid is an act of creativity. It is its own creative act. It's not seen in the same way as our journalism, and our writing, and our work, but it's still very much our own creative work and creative act. It's having to go against everything culture is telling us to be right now.

Laura: I know, from looking at your website, that your past writing was about architecture but also memoir. How is it different writing a biography?

Elizabeth: I think that my writing, whether it's short fiction, memoir, personal essay, journalism, all has a similar understructure of research. I've always been very interested in tethering the current to a larger story.

I think really for me, what I've realized over time is that the story tells you what it needs to be. Sometimes it's better in memoir. Sometimes you need fiction, because you can get to emotional truths in a way in fiction that you can't in nonfiction sometimes. There was a lot to learn in writing a biography, of course, and understanding I had to make rules for myself. That's something I find that helps at the beginning of every writing project, is “What are some of the rules I want to follow?” Because you need to have construct in order to be creative or you're just going to lose your mind.

One of the rules I made for this book was I wanted the reader to follow along with Claire in time. You're not feeling me, the writer, as much saying, "Here I am the biographer, and I'm going to zoom out to the future. Then I'm going to zoom back now and tell you this." You'll notice I zoom back to give context, but it's very judicious and rare that I move ahead in time, because I wanted it to have a novelistic feel of you being along for the ride and learning as she's learning. That helped me structure the story.

Laura: Were there any books or writers you looked to, when you were trying to figure out how to approach this?

Elizabeth: I was reading a lot of biography. I read Mary Gabriel's Ninth Street Women, which is an excellent book—it’s a group biography on the abstract expressionists. I read a lot of fashion history. That was something that I had to do. I read a lot of biography to just see how people did it, and to understand the rules of the genre.

I believe, as I teach my students, there's a great Ralph Waldo Emerson saying, "First we read, then we write," which is this idea that you learn best when you're in conversation with other writers and understanding how they've done it, and being able to read through a book and see where are those moments where you're taken and where are those moments when you're lost, and why is that happening?

I think for me, it's funny, I never thought of this as a biography as I was writing it. I almost thought of it more of a history, even though it is a biography, because I really was interested in putting and inserting Claire into the lineage of women who understood clothing to be a revolutionary act, and also the birth of sportswear. I was someone who didn't understand what the term sportswear meant. I think about leisure wear or whatever. It took me a minute to recognize what it meant to say, "We're not going to have a different dress for every time of day and for every occasion. We're going to have these clothes that we can live in and move in."

There's so much amazing fashion history right now, and a very interesting vein of women and others writing about feminism and fashion history. I also read dissertations. I read really far and wide. I read books about the history of sportswear. I read books about the history of women and housewife work. There's a great book called More Work for Mother, which was all about the birth of modern appliances and how it was supposed to make our lives easier, but in fact, it made our lives harder.

I was thinking about McCardell's desire to have her clothes be washable—they were called tubbable then because you put them in a tub. She was thinking on so many levels about the experience of the clothes, not just wearing it, but how do you wash it? How does it pack? How hard is it to clean and carry with you? I was so impressed by that range of thinking in her, that problem-solving that design can do.

Laura: It's interesting that she would care so much about it being tubbable and everything while she's not a housewife. There are these paradoxes, and also the fact that she seemed such an independent woman, but then, when she married, she married the most traditional man, who basically ignored her career. She ends up coming across as a much more complex person.

Elizabeth: Her family was solidly upper-middle class, so she had money because they were able to pay for her to go to college. They supported her in Paris. She was never wealthy. She was never rich in the way that many of the women she met on these steamships to Paris were. She couldn't forget about a budget. When she was a single woman living in New York on her own, even though she had some support from her family, and even though she ended up getting jobs that paid her well during the depression, which is nothing to sneeze at, she still had to be conscious of dry cleaning.

She didn't have a maid at first. She did eventually have domestic help. She still had to consider what it was like to be a woman moving in the world who didn't have bottomless wealth to rely on. I think even when she was someone who didn't see herself as being housewife material, she also didn't malign housewives. I think that's really interesting to me.

There were other designers at the time, like Elizabeth Hawes, who was a very pivotal designer in the birth of American fashion. Elizabeth was doing more couture work, though she did do some ready-to-wear. She ended up becoming sort of an activist. Elizabeth Hawes is another person who shouldn't be forgotten. I think Hawes was over here wanting to blow up the system: "The system's unfair. I want to explode it from within. Women should have everything." She's not wrong.

I think McCardell understood that she needed to work within the system to effect change. I think what that meant was, for a time, she was not remembered as being as revolutionary as she was. Then [Kohle Yohannan and Nancy Nolf, authors of Claire McCardell: Redefining Modernism] knew that she was. That book really helped to point out the fact that what she was doing was really, really, really revolutionary.

Laura: I think even before that [book], there were generations of designers who were inspired by her. We can look at Halston, and we can see a direct lineage. There were people who were coming across her clothes, whether they were coming across them in magazines or at flea markets or whatever, who knew that they were modern, or maybe they had seen them as a child. There's always been this continuous strand from her in American sportswear of this ease of movement.

Elizabeth: It's such a good point. The DNA of what she invented still exists. I was talking to someone the other day, a reporter, who was like, "I am admittedly not a fashion person. Why is she so important?" I'm like, "Light bulbs exist." I'm just saying this idea that she invented in 1934 in the separates is the foundation of American fashion. We no longer tether it to her name. The fact is that the proof of a great and thoughtful design is that it has longevity. What she has created has longevity.

She really was an extraordinary inventor, working within a new system of mass production, working in a new system of human-made textiles that were just being created. She invented things that we all take for granted today, and that is extraordinary. They still exist. Every designer I've talked to researching this book has said, "Absolutely, we look back to Claire McCardell, because she did it well, and she did it right, and she informs how we design today."

Laura: It's so funny how she broke so much new ground with the capsule wardrobe. Then, when Donna Karan did it with her first collection with the Seven Easy Pieces, that was supposedly breaking new ground and revolutionary. That's 50 years later. I still see designers coming out with, "I'm just making a perfect capsule wardrobe. There's too many clothes. It's too hard for people to figure it out." People are still saying the same things that she originally proposed almost 100 years later.

Elizabeth: Exactly. One of the things that I thought about a lot, honestly, was being a visionary can be a really lonely thing. Think about this: She invented separates in 1934 and was pretty much laughed out of the room during the buyer's preview because that wasn't how merchandising worked. She never gave up on it. She kept at it. Part of me is also like, "What does it take to be that person who has a vision?" If you think of a new idea as being like a candle flame, it's so easy for everybody to just come and snuff it out. There are those rare people, I think that their greatest talent isn't just their vision and their ingenuity. It's also their persistence.

The fact that she didn't give up on herself, even as the world said, "You're crazy,” and the fact that she was told by her male bosses, "These are crazy clothes," and so she called him her “crazies.” That was something that I think I really admire in McCardell is that ability to believe in herself. I think honestly, she was born with it, and it was instilled in her by her mother because even though her mother was a very traditional conservative housewife in a lot of ways, her mother was that dichotomy of Victorian era rules and a progressive modernism that said, "Believe in yourself and do it."

Laura: Amazing. She's a really fascinating person, and it's really wonderful to learn more about the person behind the clothes. Her clothes today look so modern still, and to be the kind of person who would create something that looks modern almost 100 years later… It’s really interesting to, through your research, learn more about how one becomes that visionary and how one persist in these worlds that aren't necessarily built for a visionary person.

Elizabeth: Let alone a woman. I think that the other thing that I realized is that so many biographies [describe the subjects as] iconoclasts. I started out writing about architecture really during the starchitect era, where it was like, "This genius man on top of the mountain." We all know that's not true. I think that's one of the things that I really love about McCardell, and I love about this time is that it was a constellation of women working together. It was a group effort. I think she would say, and I say in this book, she didn't do it all by herself.

I think that sometimes we have this notion in America of like, "Oh, there's some singular genius who did it." I think that undermines the reality of what it takes to really be a changemaker in the world, is that there is a system around you. There is a support network around you. Ditto with being a writer. People are like, "Oh, you did this all on your own." No, I didn't. I had archivists, I had librarians, I had researchers, I had other writers reading my work, I had editors weighing in.

This idea that even in our most singular act, it is a group endeavor, freeing up that idea, I think, reminds us that we're not alone in it, that we can create and build these networks and systems to help us realize a larger goal. Today, I see designers like Tory Burch, who has done a lot to bring Claire McCardell's name back into the public consciousness when she reissued Claire's book a few years ago [What Shall I Wear? The What, Where, When, and How Much of Fashion], and she designed a season around some inspiration from Claire. She also has a foundation that's all about female entrepreneurship and ambition.

Laura: It seems like Claire was incredibly lucky in encountering some men who really believed in her, who were mentors or just partners who believed in her and believed in a woman taking on a bigger role.

Elizabeth: Yes, that's an excellent point, because I wouldn't want to say that this is all women against men. One of the people I really wanted to better understand was Adolph Klein, who was her partner in the second iteration of her firm, Townley. I don't think what many people realize is in addition to Townley Frocks, where she made her name as Claire McCardell by Townley, she also started something called Claire McCardell Enterprises, where she created her own business with Klein as a partner to license and design other things. She really was very entrepreneurial. She really did create the modern notion of the multifaceted designer. She did everything.

She did it in concert with a man who believed in her vision. On some level, yes, she needed Klein. Absolutely, because he owned the company at first, he was the manufacturer. It was a stroke of great luck that those two people crossed each other's paths because he recognized that what she was doing was valuable, and he allowed her to take big risks.

Technically, the title of this book is her name, which some would say in publishing, "Well, that's challenging. Don't do that because the search engine optimization will be a mess. Name it something pithy and then put her in the subtitle." Luckily, and my publisher agreed, she spent her whole life fighting to get her name on her label. She was one of the first in ready-to-wear to have that happen.

It felt really important to me to give her name back. That was the whole point. That's why the book is her name. The subtitle is The Designer Who Set Women Free, but the title of this book is her name.

Empresses of Seventh Avenue

Edna Woolman Chase, Carmel Snow, Elizabeth Hawes, Claire McCardell, Marjorie Griswold, Dorothy Shaver, Lois Long, Virginia Pope, Eleanor Lambert, Diana Vreeland, and Louise Dahl-Wolfe… Some of these names are still well-known, others remembered by the most passionate fashion history fans, and some forgotten. All of these women were integral to the advan…

Town and Country with Clare Potter

“The clothes [Clare Potter] creates reflect her own blend of town career and country living… clothes that distill fashion but never exaggerate it, that move easily from one season and one year to the next.” – Wilhela Cushman, Ladies’ Home Journal, October 1947

Elizabeth Hawes on Pregnancy Fashion, 1938

One of America’s greatest fashion thinkers (and designers), Elizabeth Hawes, turned her sharp mind to the question of maternity clothes during her own pregnancy in 1938. Months after publishing her first book, Fashion Is Spinach—one of the finest (and wittiest) critiques of the fashion industry ever written—Hawes wrote an essay for the June 15th issue of