I wrote this piece several years ago for Heroine, Grailed’s woman’s site, but as Heroine has since closed I thought I would share it with you. It was Calvin Klein’s 81st birthday yesterday—this article revisits the early days of his fashion career and how he made minimalism his signature. Klein’s simple modernity can be seen in motion in this clip that I posted on Instagram a few months ago: “Calvin Klein showing three ‘feminine, sexy’ looks from his Spring/Summer 1978 collection—modeled by Jan, Kim Charlton, and Rosie Vela—on ‘The Mike Douglas Show,’ broadcast November 8, 1977.”

I’m just back from eight days in Northern California—a three-year delayed honeymoon and birthday trip rolled together—and feeling revitalized and ready to share more of my newest writings.

Would you like for me to include footnotes, like those below, with all of my articles? I’ve gone back and forth between including them—they take time to properly format, but if they are useful I would be happy to do so.

As the fashion press and industry debate Raf Simons’ departure from Calvin Klein and where this most American of brands will head next, there often appears to be a central aspect missing from the debate—the work and worldview of Calvin Klein the designer. The hiring of Simons and the collections he designed for the house almost seemed a disavowal of its heritage—that of a brand built on a modern simplicity that expressly evolved to suit people’s real lives. With little time for fantasy and clothes as spectacle, Calvin Klein spent his whole career (up until the sale of his company in 2002) refining a message of simplicity, sparseness, and sensuality that was wholly American and wholly new.

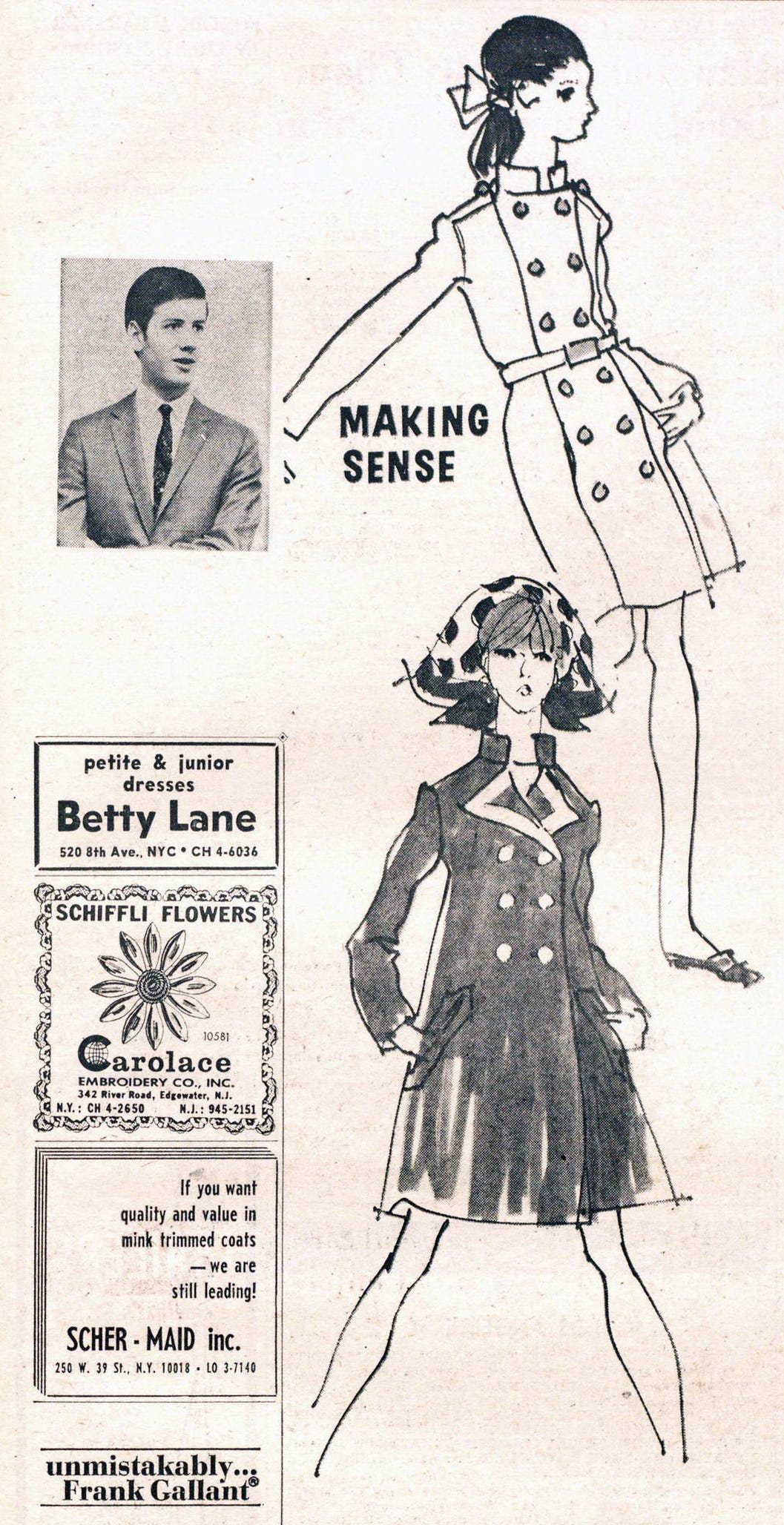

Bronx-raised Calvin Klein studied at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology but left before graduating in 1962 to take an apprenticeship at Dan Millstein, where he worked for two years. Afterward, he worked for Halldon and Hallie Jrs.—quickly proving himself highly skilled in tailored suits and coats. His dress and coat pairings had a youthful, quietly mod energy to them while still being considered appropriate for a young woman’s wardrobe. Calvin’s point of view on fashion was already highly defined—when interviewed by WWD in 1966, 24-year-old Klein remarked: “I think much too much fashion is being designed to make a big impression. As a result, the clothes may look different but they border on the ridiculous!”1

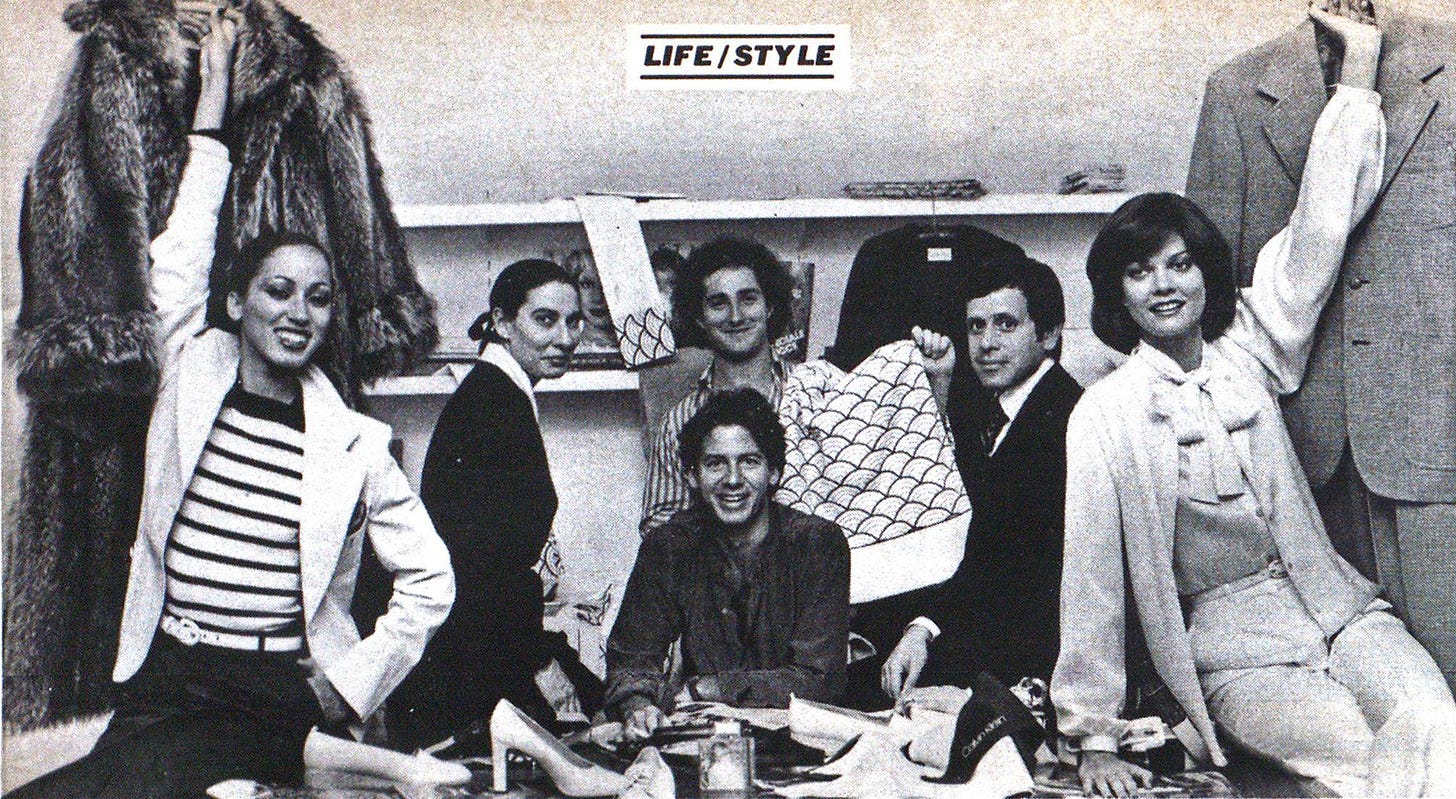

Eager to set out on his own, Klein’s childhood best friend, Barry Schwartz (then in the grocery business), borrowed $10,000 in early 1968 to establish Calvin Klein Ltd., with the two equal partners. Klein showed a small collection to the press and Bonwit Teller (the only buyer Klein knew) in March that year—only half a dozen coats and suits, but he spoke of wanting to expand “to a complete, rounded collection… to be able to do anything – to complete a total look.”2 Bonwit Teller ordered $50,000 worth, thereby establishing Klein’s worth as the next big thing in fashion. His impeccably tailored coats, jumpsuits, and dresses were an immediate hit at top department stores around the country—the New York Times reported in May 1969 that the company had already made $1 million in sales.3 While other designers were pushing fantasy clothes heavily influenced by the hippie movement, Klein’s ethos was to design clothes that “make a woman secure in her appearance as a young elegant but will never be a massive invasion of a bank account”—all achieved through superb tailoring and restrained simplicity. He truly designed for the modern woman—active, busy, liberated, and more comfortable in a chic pantsuit than a frilly gown. His idea of drama was a full-length cape flung over the shoulders and pared with a sleek white crepe evening skirt—“The cape is the femme fatale look for the ‘70s”4—minimalist with just a touch of theater.

Until 1973 Klein still lived with his wife and toddler daughter in Forest Hills, Queens—a far away world from the glamorous high fashion industry he was slowly climbing into. They divorced in 1974 and he moved into an ultra-glamorous Manhattan apartment, designed for him by Joseph D’Urso. All black-and-white-and-metal, it was a vivid evocation of the shifts also happening within his fashion designs. To break free from the early association of him as strictly a coat designer, in 1973 Calvin Klein stopped designing coats at all—forcing retailers to focus on his subdued, minimal sportswear. A smart play, as by 1974 his business had doubled from $3 million a year to $6 million. Klein’s understated designs were beloved by the press—most of them working women who wore his comfortable yet elegant pieces. By 1975 Klein had won his third Coty American Fashion Critics Award in a row and been elected to fashion’s Hall of Fame.

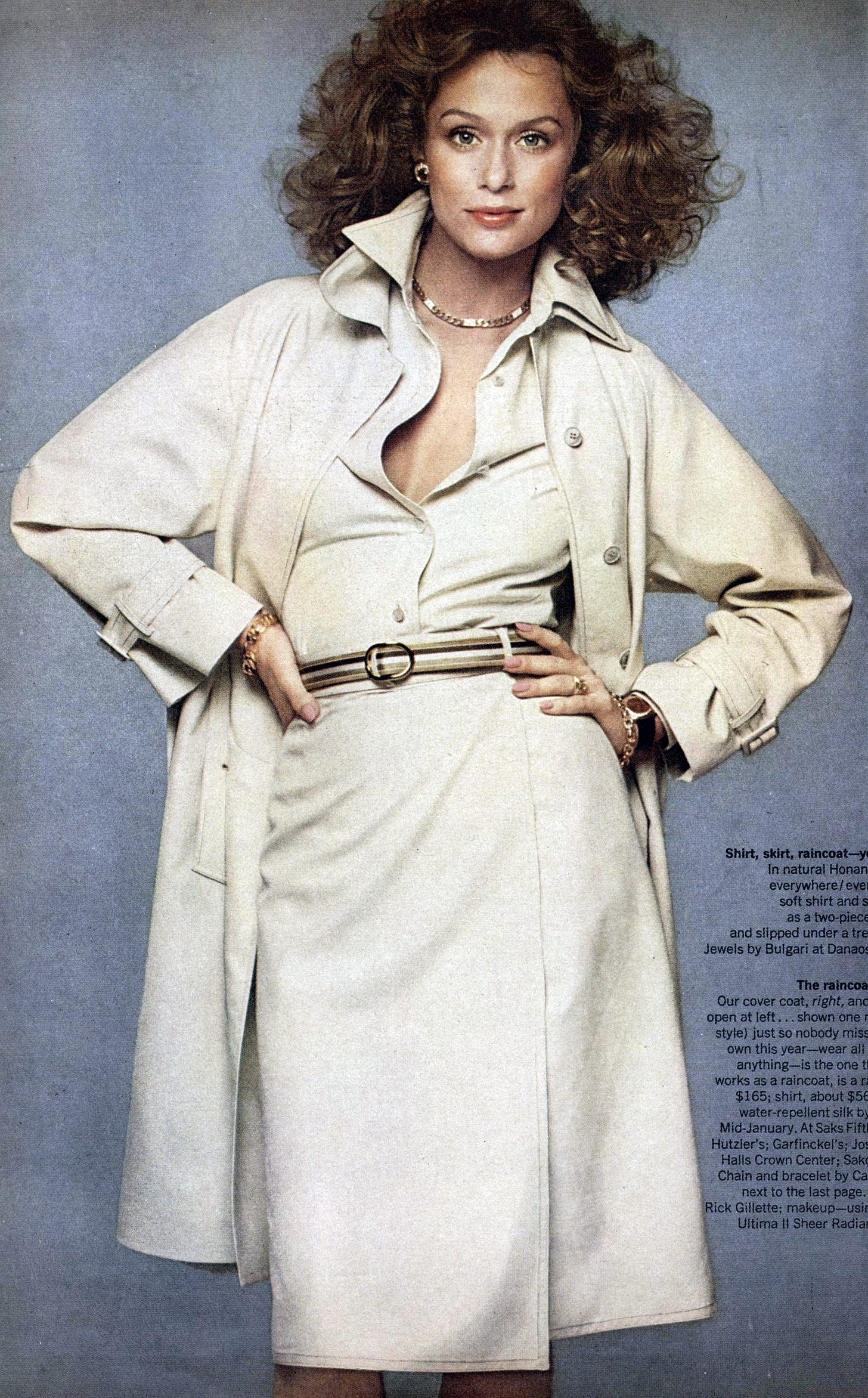

He was described as “a classicist at heart and his collection is reminiscent of the peak years of American sportswear.”5 Classic styles populated his collections (wrap coats, lean trousers, shirt dresses, pleated skirts, capes, blazers, satin shirts, sweaters in his favorite fabrics of camel hair, wool melton, gray flannels, suede, and velvet) alongside playfully pragmatic pieces like cotton poplin Bermuda shorts and bare swimsuits. What was most striking about his designs was how he took the easy, casual silhouette of sportswear and imbued it with the elegance of couture. Much of this ease was achieved through removing linings, bonding, and interfacing to create a much softer, natural drape to all of the pieces. Their sinuous femininity—with often plunging necklines—marked them as modern, liberated, cool. Grace Mirabella, then editor-in-chief of American Vogue, pronounced: “If you were around a hundred years from now and wanted a definitive picture of the American look in 1975, you’d study Calvin.”6

For Klein, he wanted to “offer as much style as we can, and the more exciting the better. It’s making clothes that are Classic and won’t be discarded in six months.”7 What was so visionary about him was his belief in separates as high fashion and in a seasonless, interchangeable wardrobe. Each collection was simply an evolution of the last, using many of the same and complementary fabrics—meaning that clients could purchase pieces that would perfectly match what they already had. His was a completely modern vision that took into account the way women really lived their lives: “As I see it, now we look to women who are accomplishing things, not rich women who wear clothes.”8 Unencumbered by ideas of tradition and propriety, Klein felt no need to kowtow to accepted fashion rules and instead brought in an easy flexibility to high fashion that is still felt in how we dress today.

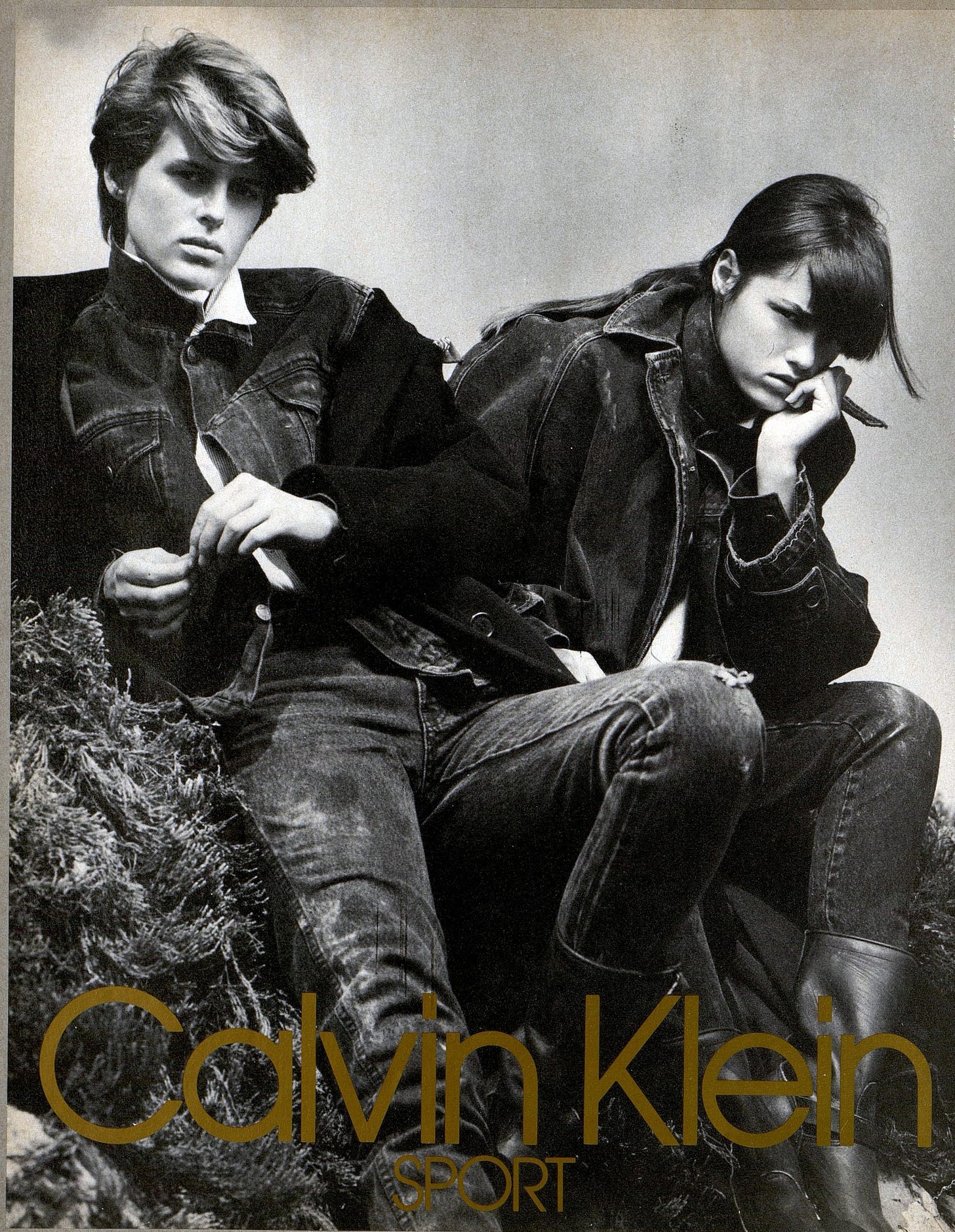

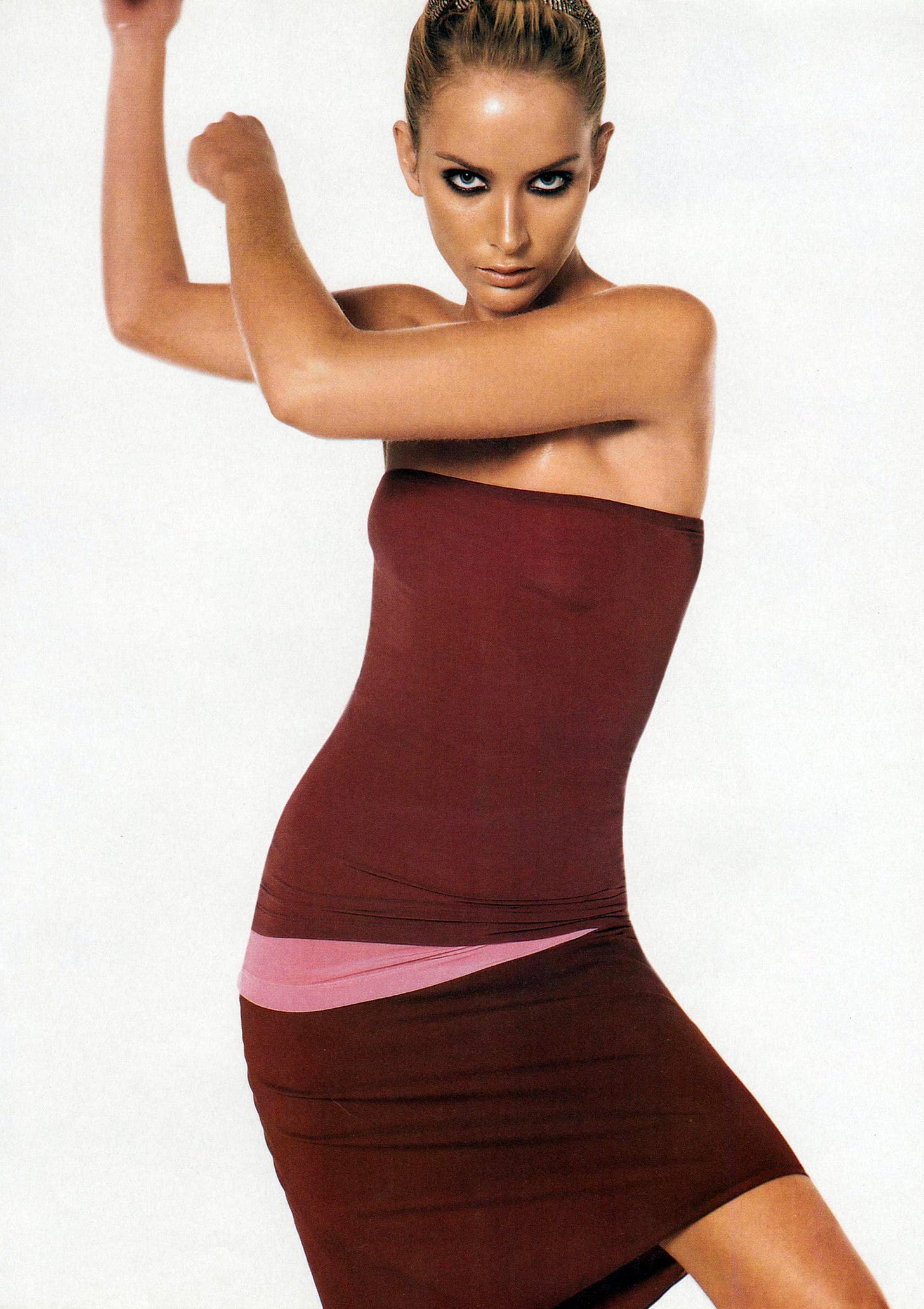

With each season, Calvin became more and more confident—his vision clearer, his tailoring less structured and increasingly soft. Modern yet sexy clothes that were “pure and wearable, yet never dull and safe… clothes that have all the right fashion looks—big, fluid, long—yet are never overpowering.”9 Looking through 1970s fashion magazines Klein’s designs leap off the page—they look as contemporary today as they did then, primarily due to a simplicity of line that few other designers came close to. While Halston was Klein’s closest peer in minimalism, Klein more comfortably designed across all aspects of a woman’s life—casualwear, loungewear, work clothes, and evening pieces—at a broader price point. Perhaps this is why Klein more effortlessly expanded into diffusion lines and denim, while Halston’s attempt to make an affordable line for J.C. Penney in the 1980s, Halston III, was met with criticism, shocked customers, and low sales. While other American designers (Geoffrey Beene, Bill Blass, etc.) started their own lower-priced RTW, more casual lines in the early 1970s, Calvin Klein had only one collection until the late 1970s when he licensed his denim to Puritan.

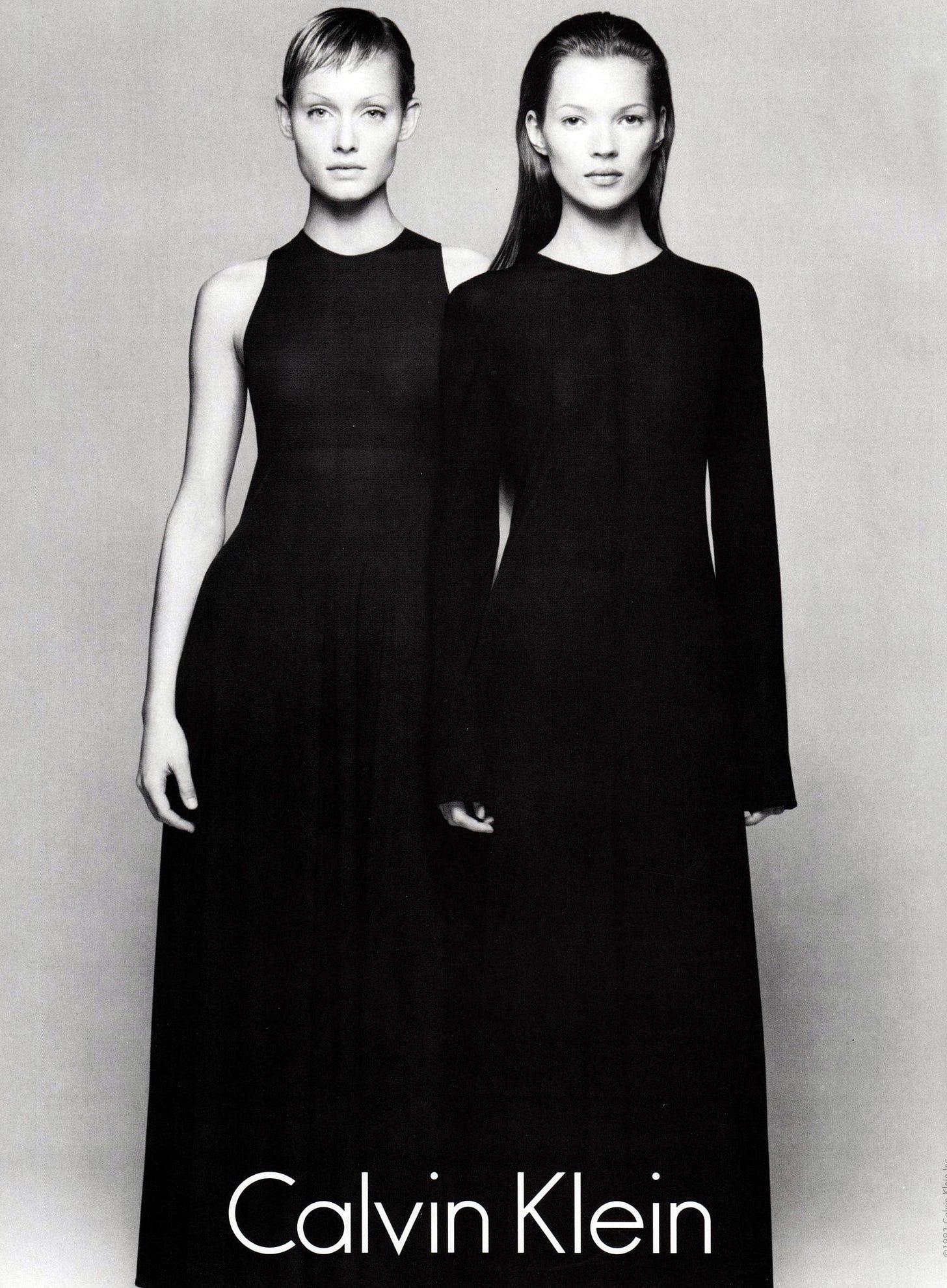

What was so exceptional about his designs was the way he infused classic American sportswear (following in the footsteps of greats like Claire McCardell) with a seamy sexuality cultivated in his new bachelor lifestyle of parties, nightclubs, and Fire Island weekends. In Helmut Newton’s provocative Vogue editorial from May 1975, “The Story of Ohhh…,” Lisa Taylor sits clad in a simple Calvin Klein dress, legs splayed, greedily eyeing a topless male model—her rapacious sexuality, loose yet revealing dress, masculine pose and energy caused a firestorm of attention. Possibly due to this controversy, Klein began to court this attention in the future—with his provocative ads of a very young Brooke Shields in his skintight denim, his ad campaigns for perfumes featuring nude models in flagrante delicto, and rapper Marky Mark posed in Calvin Klein briefs. In 1994 Klein revealed, “If people set out to be controversial, they’ll never make it. But if something is really good, interesting, and thought-provoking, you get into risk-taking and pushing boundaries and questioning values, and it can be, in the end, controversial…I didn’t set out thinking how to be controversial, only how to make this woman look to die for, a killer—with no [obvious] effort… We need newness and excitement in fashion. That’s what it’s about—that’s what puts the fun in clothes.”10 At that time he was again the most talked about and most controversial designer in the industry—Calvin’s spring/summer 1994 collection featured a parade of barely-there slip dresses that won him the CFDA award along with many column-inches devoted to what some viewed as scandalous, overly youthful designs. More of a culmination point on his journey to pure minimalism, his mid-90s collections were about the purity of simplicity: “It’s always been spare, it’s always been about sensuality, it’s always been sophisticated. And above all, it’s always represented what I think is modern.”11

Klein’s obsession with perfecting this spare elegance even in the face of changing trends led to swings in the solvency of his business, particularly during the over-the-top late 1980s and early 1990s. Yet it is exactly this strength of vision that is what should be celebrated and remembered now. While he was a genius marketer—the legendary status of his ad campaigns can’t be argued—it is the quiet strength of Calvin Klein’s clothes, along with his understanding of contemporary life’s effect on a woman’s wardrobe and habits, that truly changed fashion.

“Making Sense,” Women’s Wear Daily, December 20, 1966.

K.H., “in-Klein-ing,” Women’s Wear Daily, April 12, 1968.

Bernardine Morris, “Keeping Fashion High and Prices Low,” New York Times, May 12, 1969.

“Best of NY: Calvin Klein,” Women’s Wear Daily, May 19, 1970.

Evelyn Livingstone, “Message from 7th Avenue,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1971.

Elizabeth Peer, “Stylish Calvinism,” Newsweek, November 3, 1975.

Tom McDermott, “The boys from the Bronx,” Women’s Wear Daily, December 13, 1971.

“Calvin Klein: ‘Time has become very important for today’s woman,’” Women’s Wear Daily, January 3, 1978.

“Calvin Klein,” Women’s Wear Daily, September 12, 1974.

Bridget Foley, “Calvin Klein: Back on Top,” Women’s Wear Daily, February 4, 1994.

Ibid.