Last week’s newsletter on Jackie the ‘K’, where she spoke of having Betsey Johnson make her some custom pieces—“When I first met her I said, 'You have such a sexy body, why do you design things for a skinny body?' Her clothes are very unlike her; she's very sensual. I had her make this nice and tight”—inspired me to revisit an article I wrote on Betsey’s designs for Alley Cat. It was published in 2018 by a website that no longer exists; I’ve updated it a bit and added more images, bringing in an interview Betsey did with Rags in 1970 that I uncovered while working on The Very Best of Rags 1970-71.

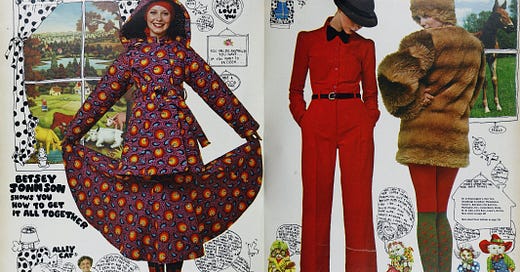

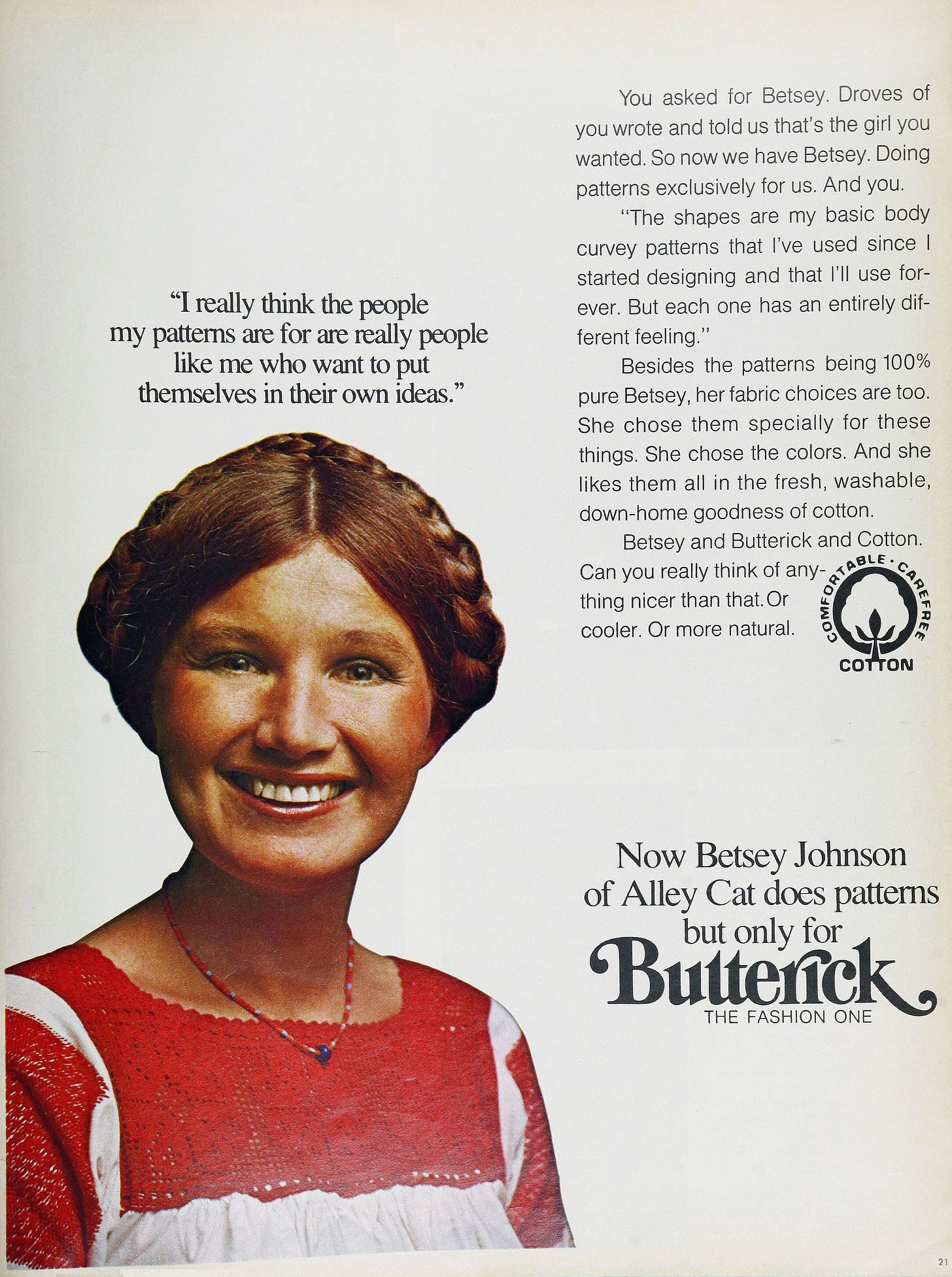

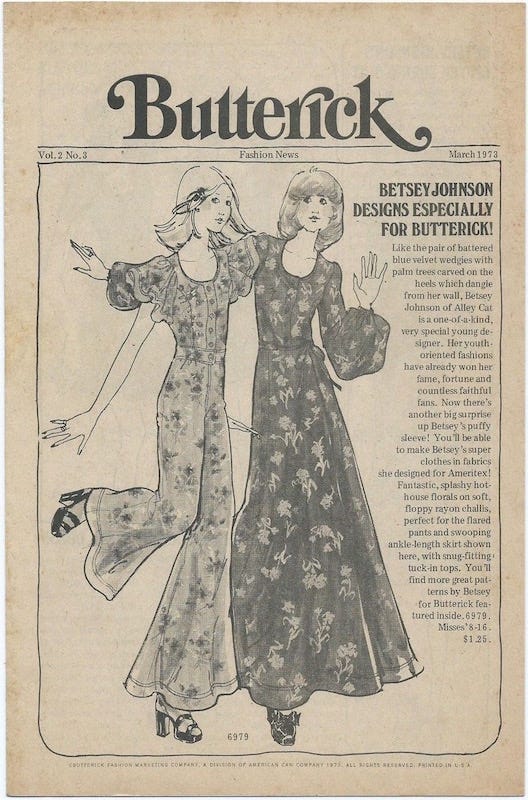

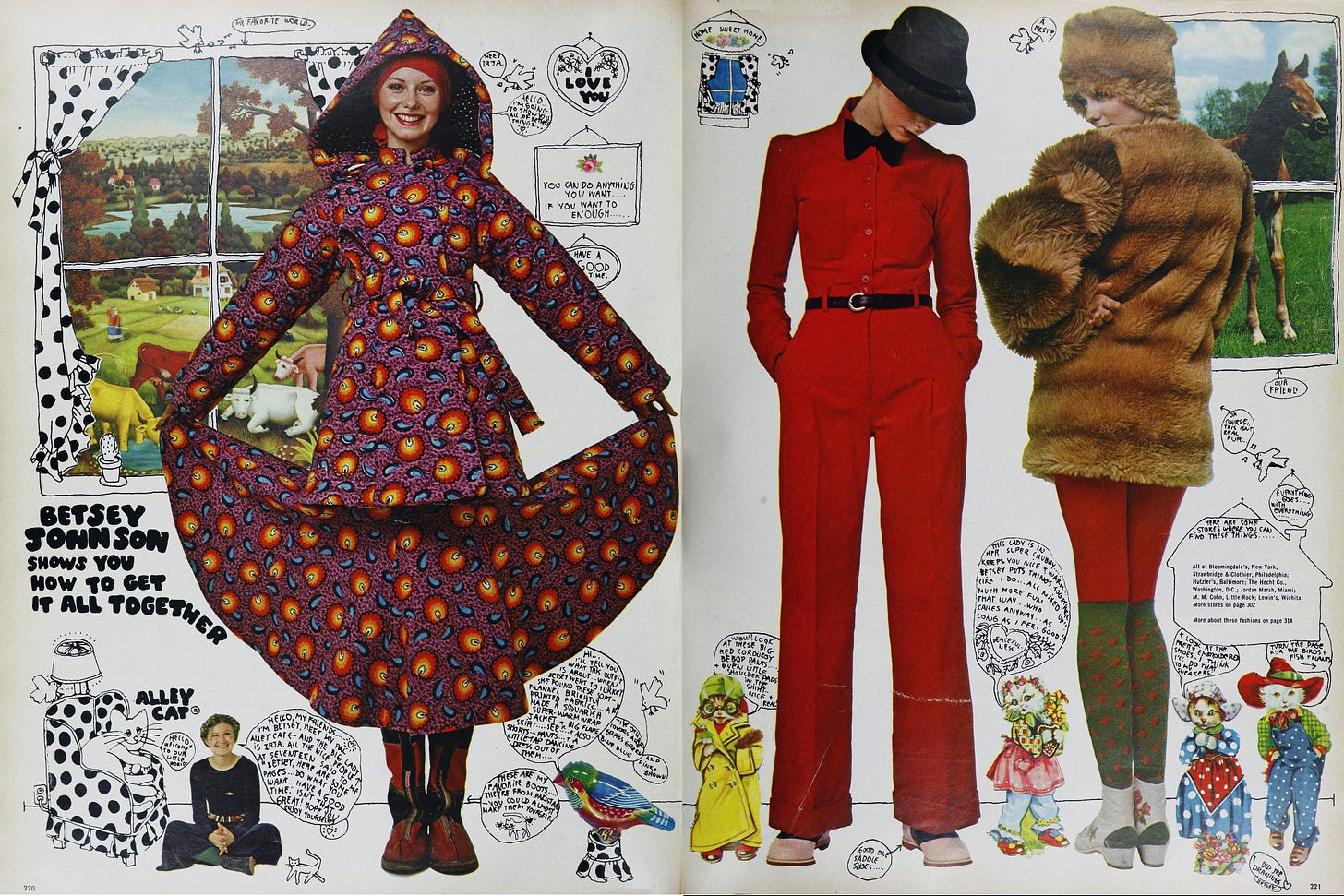

If you’ve ever looked for Alley Cat on the vintage market, you’ll know it is highly covetable and often exorbitantly priced. Betsey’s Alley Cat designs were originally in the middle price category—what she described as “not cheap and not expensive”—and available at department stores across America. Betsey considered the designs to be for 21 to 35-year-old women (though she said her fans ranged from 13 to 45), yet stores often placed them in juniors departments. A pretty calico “peasant” dress would have cost around $46 in 1970 (adjusting for inflation, that’s around $379); today, dealers are selling them for up to $845. Considering those prices, if you like the look you could always try sewing your own versions—Betsey had a very successful line of Alley Cat patterns for Butterick from 1972 to 1975. Maybe 2025 will be the year I improve my sewing skills enough to take on one of her patterns.

Speaking of Rags, this Tuesday I will be in conversation at the New York Historical Society with moderator Keren Ben-Horin and jewelry and fashion designer Debra Rapaport, talking about how DIY and street styles have evolved over the past fifty years, from Rags—which featured Debra’s designs in 1971—to the present day. Come! It should be a fascinating evening.

Betsey Johnson & Alley Cat’s Happy World of Ideas

In a fashion career spanning over half a century, Betsey Johnson’s four years as head designer at Alley Cat helped her develop and define her aesthetic. Now highly collectible, her Alley Cat pieces symbolize Johnson’s shift away from the mod looks of the 1960s to a retro amalgamation of influences that has always remained spunky, fun, and full of joy.

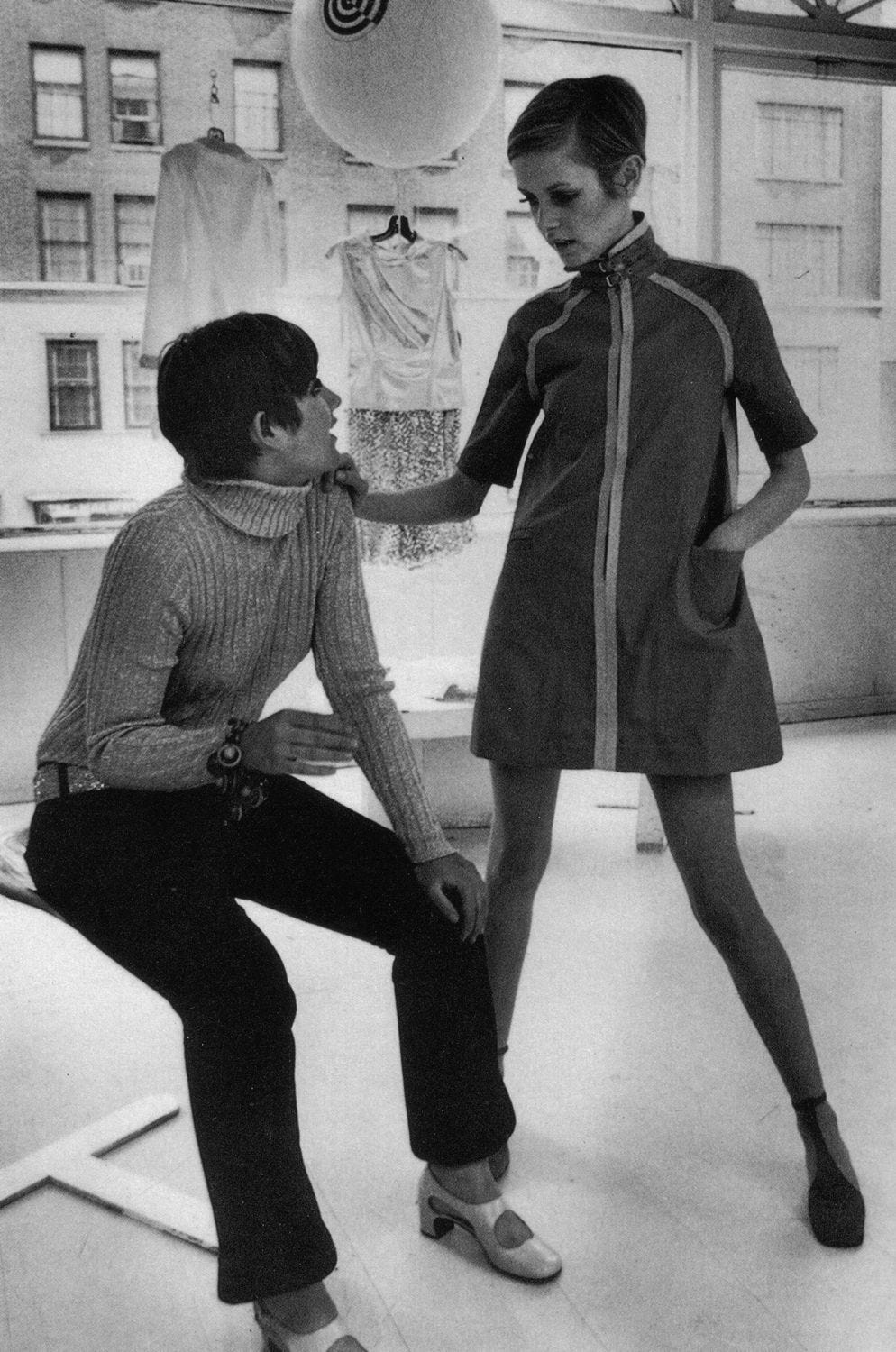

Winning the opportunity to be a college student guest editor of Mademoiselle’s August 1964 issue (a competition held every year and previously also won by Sylvia Plath and Joan Didion), Johnson immediately parlayed this into a job illustrating for the magazine. Her quirky line drawings and personal style drew attention—within months, she was designing for a shoe company, illustrating for other magazines and ad companies, and planning her own sweater business. These knit designs were pitched by Mademoiselle’s fashion editor to Paraphernalia, “a determinedly with-it New York boutique” that was opening in September 1965 and backed by the mass-merchandiser Puritan Fashions1—Johnson was hired to be an in-house designer at only 23 years old.

Recognized as a key designer of the “Youthquake” movement, Johnson designed for women who lived the same lifestyle as her—always out, running from party to Max’s Kansas City to another party, open to every new idea and opportunity. Her designs were uninhibited, at first quite mod with abbreviated swinging hemlines and made of mirrored or Day-Glo fabric. When she started at Paraphernalia, she was given free rein to design from her imagination; over time, the corporate heads behind the brand became more involved and demanded she follow fashion trends, not set them. Johnson left Paraphernalia in June 1968, revealing, “In the last six months, I didn’t know who I was, I felt I had lost control of my work. My stuff is better when it isn’t watered down. But I don’t control what’s done with it, how it’s presented. And fashion’s become a drag again. It’s become who can knock off what and how fast.”2

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sighs & Whispers to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.