The Slenderizing Magic of the Aris Isotoner Beauty Suit

Contouring from Hand to Body

Open Instagram and you’ll likely be assaulted by posts (either ads or influenced sponsored content) shilling such things as Skims, cleanse programs, LED masks, and workout equipment. The relentless pursuit of a trimmer figure and a more youthful face is nothing new—in fact, the constant barrage of “revolutionary” new products promising youth, beauty and thinness are boring in the repetitiveness of their message and lack of results over the decades. The ideas are the same—the reinforcement of damaging beauty standards the same (even as beauty standards themselves have changed). The Skims, the Spanx, etc. will someday simply be footnotes in history—a reminder of our current epoch’s body preoccupations in much the same way that the subject of this newsletter reveals those of the Seventies (i.e. nothing much has changed). While this is an article about body modification garments, it starts and ends with gloves.

The beginnings of the Aris Glove Company are a little difficult to tease out—rudimentary searches state that it was established in either 1910 or 1918, but neither is correct. What is clear is that Aris was a brand name given to imported gloves from France by Steinberger Bros. Glove Co., but not until the latter half of the 1920s. First known as Steinberger & Kalisher and based in California, this company started by importing gloves from Germany around 1911. Likely due to the war, they switched to importing gloves from France. In 1922 they opened a New York office with a Mr. Lobl, leading to the brief renaming of the company as Steinberger Bros. Lobl Co. Throughout this same period, a separate French company, Chanut et Cie, was also importing gloves from France into the United States. As early as 1915, Paul Chanut’s company was manufacturing gloves in their own French factories for the American market. Both Steinberger and Chanut et Cie sold their gloves at the same types of department stores, like the legendary Joseph Horne’s in Pittsburgh.

Arthur Steinberger came up with the name “Aris” to stand for the initials of his three sons, Arthur, Robert, and Irwin Steinberger. The earliest mention of “Aris Gloves” that I could find was in the ad above from December 1926, advertising suede and leather washable gloves. At the bottom of the ad is a logo for “LAVARIS,” a term that Steinberger Bros. trademarked in January 1927 for leather gloves. In May 1928, Steinberger Bros. and J.M. Chanut & Cie. merged. The merger allowed the companies to streamline and economize their production—Chanut in charge of all production in France with Steinberger handling all importation and distribution, while all separate brand names were retained. Sources online incorrectly state that Paul Chanut founded Aris—as the above makes clear, Chanut only became associated with Aris in 1928. He took over the majority of designing for all Chanut and Steinberger brands, while also managing the factories, though in 1929 Coco Chanel had a contract designing gloves for Chanut. In 1935 Steinberger Bros. opened a factory in Gloversville, NY, for the production of fabric gloves, all designed by Paul. At around the same time, Paul opened Gants Aris on the Rue Saint-Honoré, Paris’ chicest address. Aris was now the main and most luxurious of all Steinberger-Chanut brands—Joan Blondell, Bette Davis and Olivia de Havilland were even featured in their ads and the company also produced styles for the runways of couturiers like Molyneux and Schiaparelli. Steinberger’s three sons became partners in Aris, and in the late 1930s, they changed their surnames to the anglicized Stanton.

Cut to 1966. The name Aris is now linked inextricably with luxury gloves, sold at all of the finest department stores. The president of Aris, Lari Stanton (Robert’s son), is a self-described “health nut” who approaches a dermatologist to see if there is a way that gloves can be used to improve the look of a woman’s hands. The doctor conducted controlled tests with different fabrics on a group of fifty 30 and over women. Stanton took the doctor’s recommendations to fabric manufacturers in Europe: “We met with a gamut of manufacturing problems, and had to develop new techniques. The design of the glove does not differ from our regular fabric line. But the cloth—and the processing of the fibers is revolutionary.” What they developed was a fabric they named “Isotoner”—a combination of "isometric" and "toning" to reflect the comfortable fit of the stretchy glove. A Lycra Spandex and nylon blend, Isotoner acted “to increase circulation, and to flatten veins of the backs of hands.” Premiering in October 1969 as the “Hands Beautiful” line, Aris sent special consultants out to all their stores while newspapers alerted their readers to these new “wonder” gloves: “Just put on a pair. A tingling feeling tells you something is happening. You’ll feel an exciting isometric action right to your finger tips. Your hands get a massage each time you move them.” At the exact moment when the youth revolution made gloves no longer an essential outfit element, Aris had discovered a way to make gloves both more comfortable and more covetable. The line was instantly a success with $1 million in sales in less than a year.

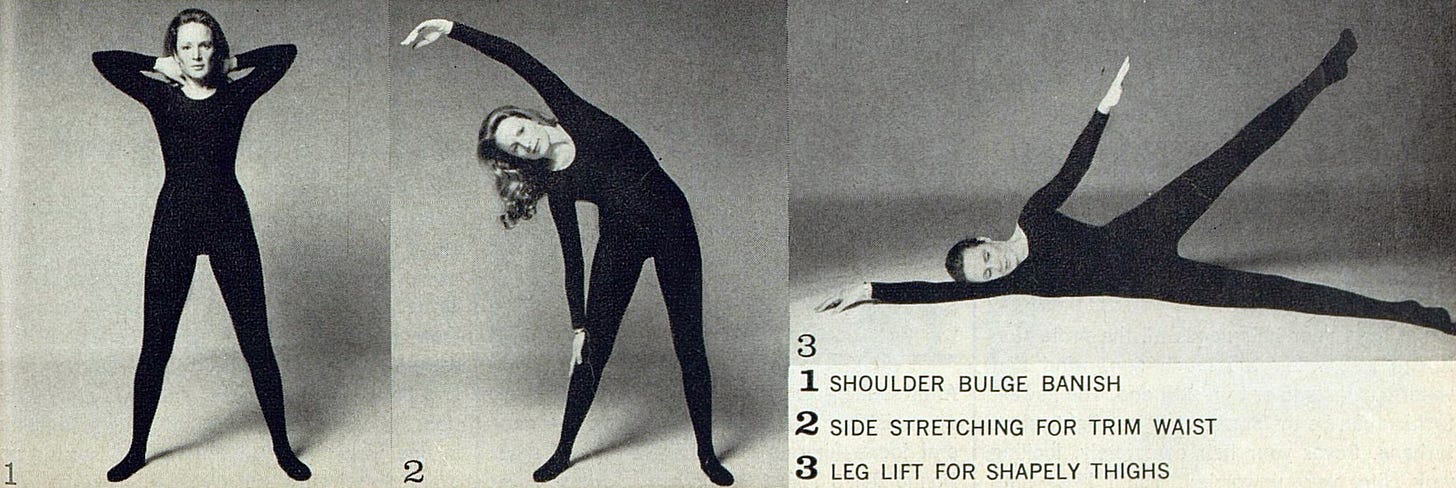

Seeking to find uses for their new wonder fabric—and still pursuing his own anti-aging program—Stanton expanded Aris beyond gloves for the first time in their forty-year history. In November 1970 Aris came out with the Isotoner Body Beauty Suit. Priced at $70, it came as a set of a leotard, a pair of tights, and a two-ounce jar of Isotoner Motion Cream. According to Stanton, the fabric’s four-way stretch acted on the skin like a massage and mild exercise; the cream was a greaseless lotion said to work with the suit to help the skin’s natural moisture come to the surface. The long-sleeved leotard and tights were designed to be incorporated into one’s outfit and worn all day, to “help tone thighs, hips, waist, arms—any curves that you’re not quite satisfied with.” Vogue called it a “skin gym” that “shapes you up even when you’re lying down.” With traditional girdles out of fashion, the Isotoner Body Beauty Suit was simply a newer incarnation—a highly stretchy allover girdle of spandex that pulled in every inch of the body while promising to massage those inches away.

An interview with the Aris Isotoner fashion coordinators, Virginia McCue and Arlene Fleischman, allowed how they were very aware of FTC restrictions around what they were allowed to say about the product’s abilities, though advertisements often skirted very closely towards promising dramatic changes. According to McCue, “We don’t say it tones muscle or that it makes you lose weight. We state that it holds you in the proper posture. When you stand properly, you also tend to pull yourself in.” The bodysuits were originally carried in the cosmetics departments, alongside Aris’ other new inventions: an eye mask and a chin strap. Aris Isotoner’s “Chin Beautiful” strap snugly covered the throat, neck and chin, with a strap encircling the forehead. One applied a special Isotoner cream which “moisturizes and mollifies your wrapped-up skin, while the strap does its self-action massage.” They recommended to wear for 30 minutes or overnight—this was definitely not a product to wear in public. The “Eye Beautiful Masque” was to be worn with the “Eye Beautiful Cream” for smoother and younger-looking skin. Results were promised within thirty days.

As bodysuits were already having a fashion moment, sales of the slenderizing Isotoner were brisk at high-end department stores. The hosiery buyer at Bergdorf Goodman was the first to rescue the bodysuits from cosmetics, giving them a special section where they were merchandised as a fashion essential—leading the way for other stores to follow with Isotoner display areas. Bergdorf’s featured a brown one in their window as part of an otherwise full Givenchy look, while George Stavropolous’ fall/winter 1971 bride was clad in a white Isotoner with a white chiffon dress swirling atop. Geoffrey Beene designed a series of Beene Bazaar separates to be worn with the Isotoner. At first only available in black, camel, white, brown, navy and burgundy, for holiday 1971 they launched the bodysuits in silver and gold stretch lame—the Philadelphia Inquirer suggested pairing them with Malcolm Starr and Giorgio di Sant’Angelo skirts for a New Year’s Eve look. The following year Marilyn Lewis of Cardinali designed a line of Isotoner suits in fashion prints plus a couple of “jeweled numbers.”

Socialites adored them. The already very thin Gloria Vanderbilt told Harper’s Bazaar, “I wear one all the time. I think they’re wonderful; I have about 10 of them—black, white and beige. During the day I wear them like pantyhose, and in the evening, if I’m wearing a long light-colored dress, I’ll wear a white one.” She added, “It’s not that I feel they really do any good; it’s just that they make me feel so good, so tightened and so sculpted.” Under all those Adolfo skirts and dresses in this and this newsletter? An Isotoner Body Beauty Suit.

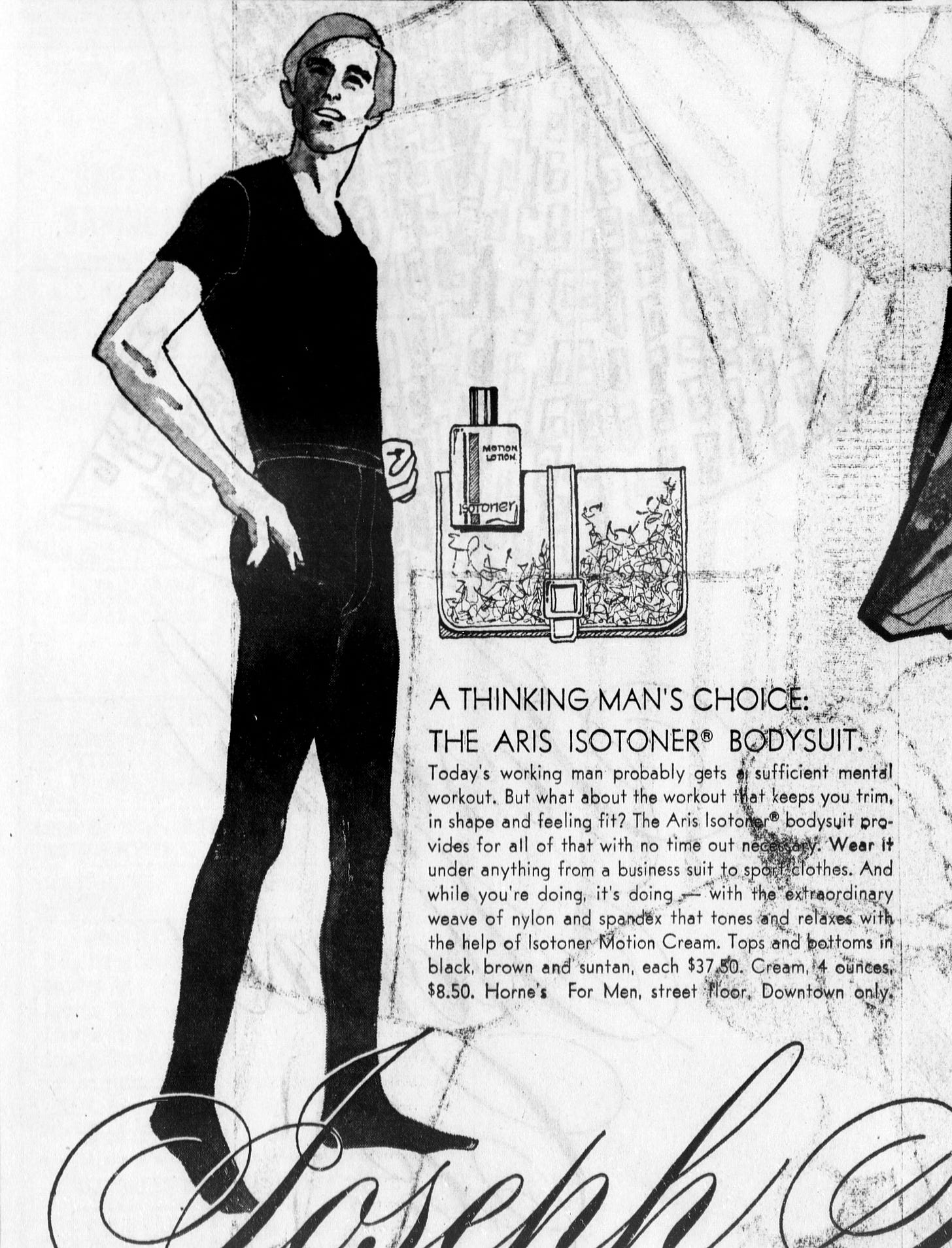

The Aris Isotoner Bodysuit for men launched in February 1972: “Today’s working man probably gets a sufficient mental workout. But what about the workout that keeps you trim, in shape and feeling fit? The Aris Isotoner bodysuit provides for all of that with no time out necessary.” Aris suggested wearing it under one’s business suit.

By 1973 Stanton was declaring to WWD that Aris was “the Mercedes-Benz of the bodysuits.” Though priced considerably higher than other bodysuits, Aris’ bodysuit did $1.5 million in sales in 1972 (just 20% of the company’s total sales). The line now comprising of 15 to 20 styles with new styles and patterns released six times a year, Aris’ designer Elayne (no surname) said the secret of their success was that they were “fashion with a secret.” No longer emphasizing the toning benefits or the need to wear with the Motion Cream, Elayne and Stanton instead spoke of the bodysuits' slenderizing effect—so sculpting that Elayne stated wearing a bra was necessary to prevent looking “like a washboard.”

While “Eye Beautiful” and “Chin Beautiful” seem to have had limited success, Isotoner bodysuits and (in particular) gloves reshaped a huge number of American bodies and hands in the 1970s. It is unclear when the bodysuits stopped being produced, though I did find a mention of them at an inventory clearance sale in 1978—selling for $5.99 versus the original $50+. Aris Gloves itself had been purchased in 1969 by Consolidated Foods; in 1978 Consolidated took over Hanes and placed Aris under the management of Hand’s chief executive. It seems likely that this shake-up resulted in the streamlining of their offerings. Aris seems to have decided to focus on what they knew best: gloves. They continued to produce styles using Isotoner—winterizing them, making new fashion styles—but ads leaned less on their “relaxing,” “massaging” fibers. During the Christmas 1983 season, many millions of Aris Isotoner gloves were sold across America. In 1985 Consolidated Foods changed its name to Sara Lee; then in 1997, Sara Lee sold Aris Isotoner to Bain Capital who integrated them in with Totes—creating Totes-Isotoner. Isotoner gloves and slippers (a product they introduced in the eighties) are still available today—sadly no assurances of “Iso-Massage” to be seen. It’s worth noting that two of the most famous gloves ever were from Aris Isotoner—the blood-shrunken leather gloves that helped acquit O.J. Simpson.

Body contouring garments as fashion, promising to remold one’s shape into the stylish one of the moment—Skims or Aris Isotoner? Though there were no celebrity figureheads for Aris, the larger connections between the companies (and the industry as a whole) can be seen. We are forever chasing that product that will (finally, this time) change our body-face-neck-hands forever.