Originally I planned on writing about the use of antique quilts in Adolfo's designs, reflecting today's obsession with quilt coats, but this piece became more of an exploration of the start of his apparel career. I love Adolfo's early work—it is basically how I want to dress every day—but I feel that he isn't discussed as much as he should be, or only discussed within the context of dressing Nancy Reagan. Like so many designers that I'm interested in, he is usually relegated to a sentence or two in fashion history books—the same situation that led me to write a book on Thea Porter (any publishers out there want to help me write one on him?) He passed away in November at age 98 and I’ve been meaning to write about him since then—open the story up a bit, delve into his creations in greater detail.

This is a two-part journey through three years in a designer's career as he expanded from milliner to couturier to ready-to-wear designer. Today is a bit of background on Adolfo but mostly concentrating on 1967-68, and Saturday's subscriber post will be 1969-70.

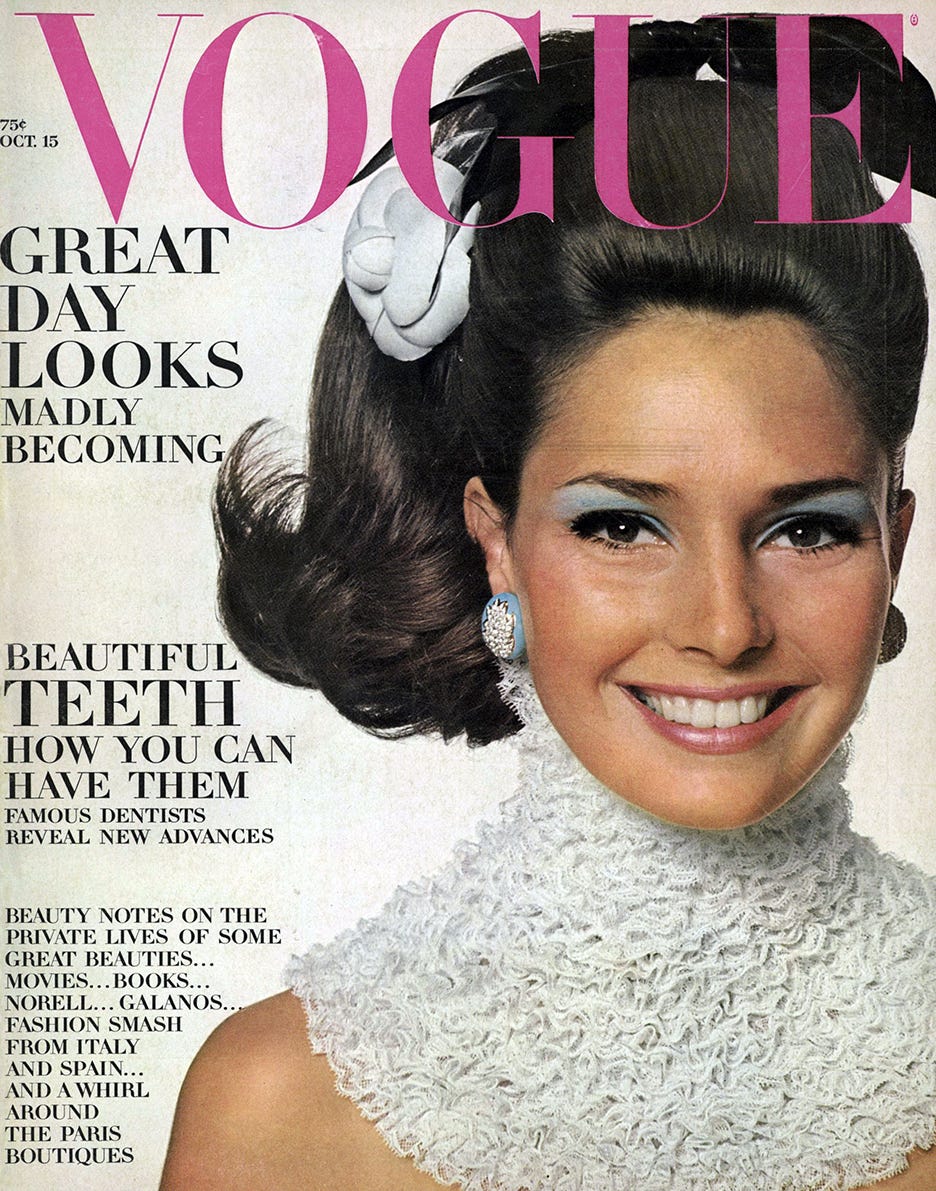

Adolfo Sardiña was born in Cuba in 1923. He was raised by an aunt who wore French couture, who encouraged him to pursue a career in fashion. At twenty-five, he moved to New York before apprenticing in the millinery department at Balenciaga in Paris from 1950–52. When he returned to New York he became head designer of the millinery company Emme (later one of his main rivals in headgear). Adolfo won his first Coty Award in 1955; four years later he won the Neiman Marcus Fashion Award. Early in 1962, Adolfo split from Emme and was beset by offers from potential backers for his own company. With financial backing from Bill Blass (for whom Adolfo designed hats), he signed a lease for the third floor of 22 East 56th and soon established his own salon; his first solo millinery collection followed in July 1962 and was a "smash" according to WWD. All custom-made and only available in his salon, it was not until 1965 that he began a high-end ready-to-wear line of hats for Saks Fifth Avenue; earlier, in 1963, he began designing two lower-priced, mass-market lines.

A close confidante of many high society ladies, Adolfo seemed particularly tuned-in to what would excite them and make sense in their lives. In his first few years producing apparel in addition to his hats, he often designed silhouettes and styles that seemed surprising to fashion journalists still captivated by the mini. After catching the Russian film adaptation of War and Peace while in Paris, he designed a collection of hats inspired by it for fall/winter 1967. Unable to find clothes that suited these "Cossack" styles, Adolfo had a seamstress run up full, mid-calf felt wrap skirts. Before the millinery collections in early July 1967, he told WWD: "It's different, yet practical. I am tired of shorts and my ladies are, also.” Worn over leotards at his show, the silhouette looked new and fresh. His high society clientele—those at the forefront of trends like Gloria Vanderbilt Cooper, Mica Ertegun, Chessie Rayner, and Ethel Scull—immediately came calling. He wasn't the first or only to experiment with that length, but his wrap-and-tie skirts were the fullest—when cinched tight, they created the effect of a perfectly tiny waist. Gloria ordered six in different colors of felt and velvet, while Ethel bought a dozen.

As everything was custom-made in his shop, it was easy for Adolfo to add items where he saw missing spots in his clients' wardrobes—sometimes a style here and there, outside of the formal need for a fashion show. That fall his ladies all appeared in felt midi capes, followed by long-length weskits."It's terrific. He's come up with the solution of what to wear over the midi skirt…" Vanderbilt told WWD, "This whole cape thing is wonderful…so right for now. Just watch it catch n like wildfire." For his spring hat show in January 1968, he looked to Elvira Madigan—ruffled jabots and collars, white organdy midi skirts, and artificial flowers appliquéd all over vests or midi skirts ($350 to order, or almost $3,000 today). Without waiting for spring, within a month Vanderbilt and Skull had been photographed on the town in them.

Enchanted by the romance and the drama of these looks, Vanderbilt asked Adolfo to make her one of his vests and full, midi skirts in a red-and-white gingham to wear to the premiere of the musical George M! in April. Afterwards, Bill Cunningham remarked, "Many observers felt that the winsome, old-fashioned gingham checks made the conventional brocades and beaded gowns of the usual opening night audience look a little passe." Vanderbilt's fellow socialites were all on the phone to Adolfo the next day and two weeks later WWD printed a large spread of all the custom gingham looks he had designed for his ladies. "Gingham—red and white cotton gingham—is American fashion. It grows on you. It is gay and patriotic at the same time." Combined with the white organdy so central to his spring/summer collection, these full-skirted pastoral fantasies were the talk of the New York social scene. Having worn his hats while First Lady, Jackie Kennedy ordered a navy and white gingham skirt with matching kerchief to wear to the wedding of Eliza Lloyd (daughter of Bunny Mellon, one of her closest friends).

Vanderbilt and Adolfo began to collaborate on more clothes. As an artist herself, she had a clear aesthetic sense and a vision for herself that was closer to her artworks than what was available in most shops. According to Bill Cunningham, "Until Adolfo's dream dresses came along, Mrs. Cooper was an all-Mainbocher, understated couture client. She has now moved into Adolfo's fantasy world, effectively wearing the most Bo-Peep of his creations." With Adolfo, she could bring him an idea that he would then magic into a full ensemble. After the gingham, he designed a heavily ruffled flamenco dress for her. While visiting Vanderbilt in her painting studio, he saw collages for an upcoming show—portraits of Queen Elizabeth and Mary Queen of Scots made of gingham scraps and lace backed with aluminum foil, gold and silver doilies on backgrounds of cotton gingham—and was thereby inspired to design a series of outfits for her. The most exquisite of all was the Elizabethan dress she wore for her May 1968 opening at New York's Hammer Galleries. According to Adolfo, it was "inspired by Gloria's 'Queen Elizabeth with Bows' collage. There's an enormous ruffled collar of layers of organdy and silver lace… lilac and pink ranunculi on the tight bodice…a full skirt of silver lace over lavender organza." Thick white foundation and sharply pulled back dark hair further enhanced the vision of Vanderbilt as one of her assemblages.

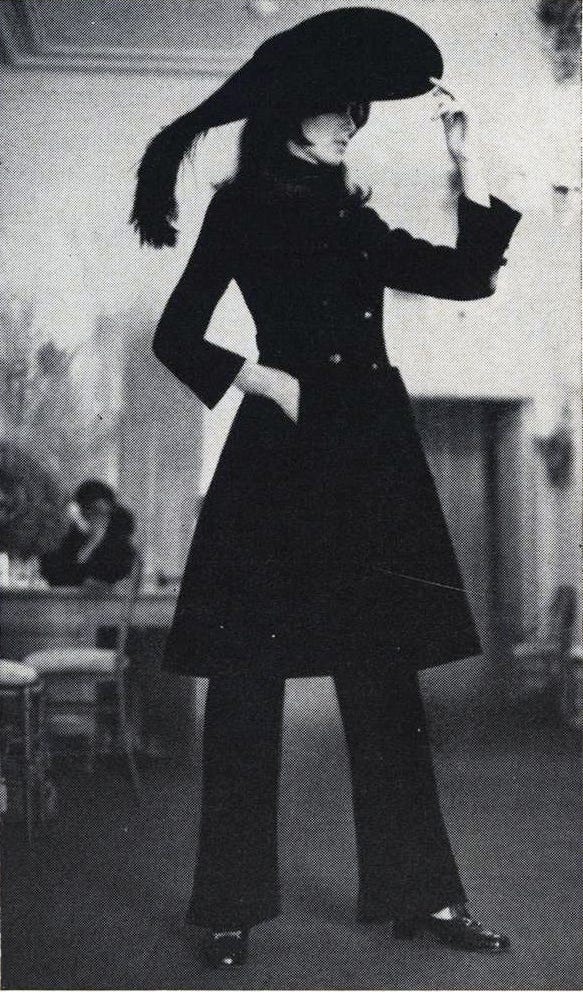

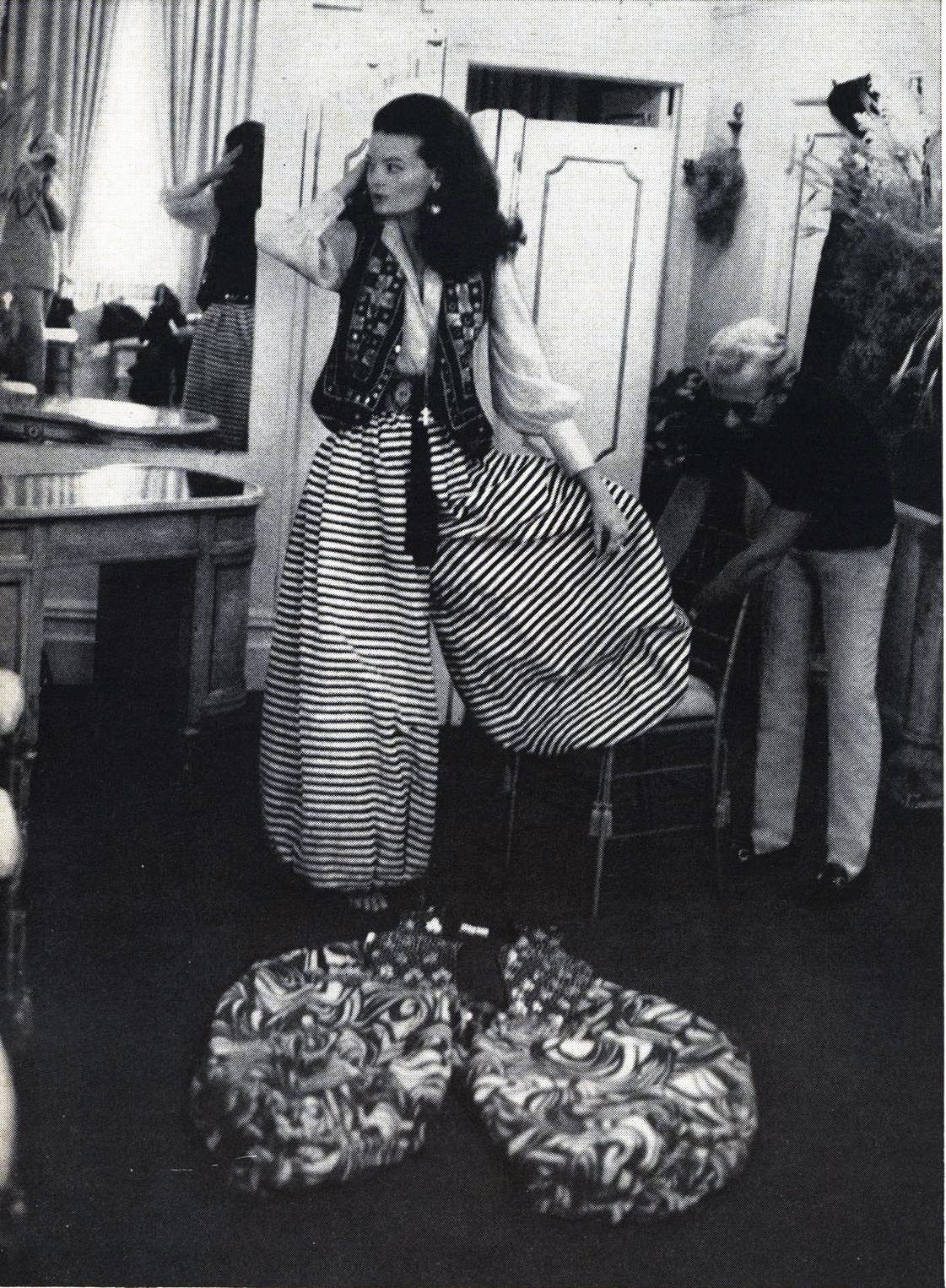

That summer he designed fantasy "Turkish harem" looks of felt boleros and striped cotton or solid felt pantaloons—some of the harem pants so full that they needed to be "picked up like skirts going up and down stairs." Saks created a new Adolfo Boutique in-store for which he designed his first ready-to-wear line for fall 1968, based on the same theme and inspired again by Gloria. At the luncheon opening, she modeled three looks including very 1930s-inspired brown suede pants paired with a suede-bound white sweater jacket as well as paid of extra-full lame harem pants with a matching bolero and ruffled blouse. Jackie Kennedy stopped by Adolfo's salon to order several pairs of harem pants with matching boleros (trimmed with gold coins) to take on her trip to visit Aristotle Onassis on his yacht; she also ordered his long black midi melton coat, matching trousers, black lamb and felt vest, black felt skirt, black velvet weskit, and white shirt for running around the city. Even the Duchess of Windsor—never known to wear pants—ordered a pair of black velvet pantaloons. After just one year of clothing design, Adolfo was now outfitting his socialites from head to toe (sock).

The common thread between all of these collections was a romantic revivalism that had the proper "wow" factor for women whose style was chronicled daily in the newspapers. In the words of Eugenia Sheppard, "His little salon on East 56th is just the kind of place where it's easy for off-beat ideas to start, and Adolfo has the right clients to start them." With a tiny team, Adolfo supposedly did everything from sweeping the floor to talking to every customer—the key to his success. The day clothes were chic, elegant, and easy to mix and match; the evening clothes, whether for at homes or parties, were original, striking, and fun. All were flattering. For the ladies who shopped at his salon, they were also endlessly customizable—preventing the likelihood of running into anyone dressed the same (though his fans often planned to turn up in Adolfo gingham or organdy looks en masse).

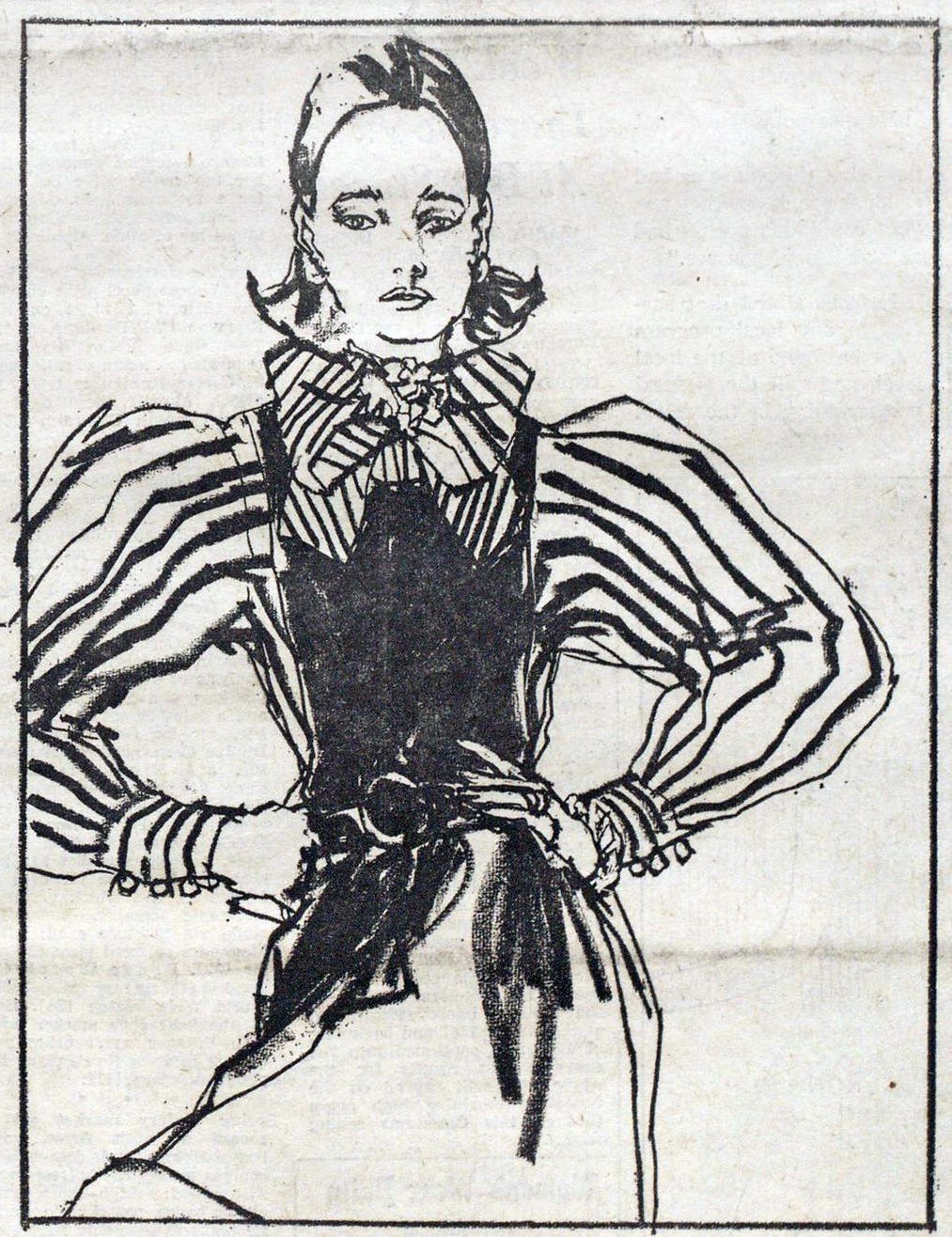

Late fall 1968 he began making elegant pinafore jumper dresses—with a small waist and full skirt they could be worn over any blouse (simple white for someone like Chessie Rayner or lavish striped silk for Gloria). Most socialites ordered them in multiple lengths.

Gloria ended the year hosting a lavish dinner for Viscount Maugham at the Coopers townhouse, where she wore Adolfo's "long full black velvet skirt, a black high-necked, long sleeved blouse, a garnet velvet weskit embroidered in jet and black ostrich feathers, a diamanté belt around her narrow waist, great gloopy diamanté earrings, hanging necklaces, several bracelets and rings on almost all her fingers." In the words of gossip columnist Suzy Knickerbocker, "The Lily Maid of Astolat never looked that good in her life." Even the New York Times was saying, “It’s almost axiomatic today that if an event is social and fashionable, it’s Adolfo territory.” Adolfo, fantasy, and society were now deeply commingled—a mixture that sprouted seemingly endless historical creativity.

As Adolfo said in November 1968: “Chic and decent clothes are not enough. Clothes should be amusing. Fantasies are important when the world is in such an unpleasant mess.”

Sign up below for a paid subscription to read more on Saturday.