While American fashion in the 1930s was commonly understood to be solely an industry of copyists, two aspects of American culture did have a wider influence on dress. One was with sports clothes—garments made for tennis, bicycling, and other sporting activities that active American women made fashionable—and the other was Hollywood.

When we talk about the rise of American fashion—as Nancy MacDonell covers in her book Empresses of Seventh Avenue and as we discussed in our conversation last week—it is usually in regards to the push to center American designers when the Paris couture went offline during WWII, yet even earlier Hollywood was influencing fashion trends. As Nancy mentions, the New York fashion press had little respect for Hollywood costume designers; she explains, “…to the fashion elite of the era, [Hollywood costumes] were vulgar and showy, the opposite of refined Parisian good taste.” Unlike the fashion press and New York manufacturers pre-war, Hollywood costume designers were not slavish followers of Paris—they didn’t have time to be. As famed costume designer Adrian writes below, “A month after a French gown is shown in New York, or published in your magazine, the copies begin to flood the land. Our pictures are not released until three or four months after they are started. If I took a dress already popular, and copied it in a picture, ladies in the audience might already be wearing copies of it and the whole film would appear to them passé.” This meant that throughout the 1930s, Hollywood costume designers had not just to gather inspiration from the collections and many other sources but also attempt to tap into the zeitgeist and come up with something that would look as right six months later as whatever Lelong or Chanel were dreaming up for their future collection at the same moment. Watching a silk gown rustle across the screen brought fashion to life more vividly than a static fashion illustration—the combination of visual movement, sound, and the romance of the story proved intoxicating to the regular woman, who found herself needing to have a dress she’d seen on screen, even if it was only a cheap imitation. As much as Paris was copied, so was the cinema.

In her book Nancy discusses how, during the summer of 1940, after the fall of Paris, New York fashion editors journeyed to Los Angeles, begging costume designers—whom they had formerly looked askance upon—to help the American fashion industry now bereft of Parisian couture to copy. The costume designers rejected their pleas to design for Seventh Avenue, suggesting the editors cultivate their own designers (like Clare Potter and Claire McCardell, who were already working in the industry) and new sources of inspiration.

Reading that, I was reminded how, six years earlier, Adrian recorded his thoughts about American fashion and Hollywood costumes as an instigator of fashion trends in an essay for Harper’s Bazaar. Fresh from designing the first truly mass-copied movie costume—Joan Crawford’s organdy confection in Letty Lynton, with Macy’s alone selling more than 50,000 of a $10 version—he was well-placed to survey the interconnections between Hollywood and the garment industry. Years before the likes of Dorothy Shaver and McCardell would work to create the “American Look,” Adrian pushed the idea of American fashion free from Parisian influence: “Nor is great fame to be won by translating from the French. An artist who signed his name to a copy of a Gauguin would be booed out of the galleries by the critics. The cribber of Hemingway would be sued to bankruptcy by the copywriters. There seems to be no compunction about appropriating a shoulder or a hemline or a frill. If American design is to flower and go down in history, it must stand on its own feet.” Luckily, the American fashion industry eventually caught up with his thinking.

DO AMERICAN WOMEN WANT AMERICAN CLOTHES: Hollywood’s foremost fashion designer discusses our sudden furious yearning for native dress

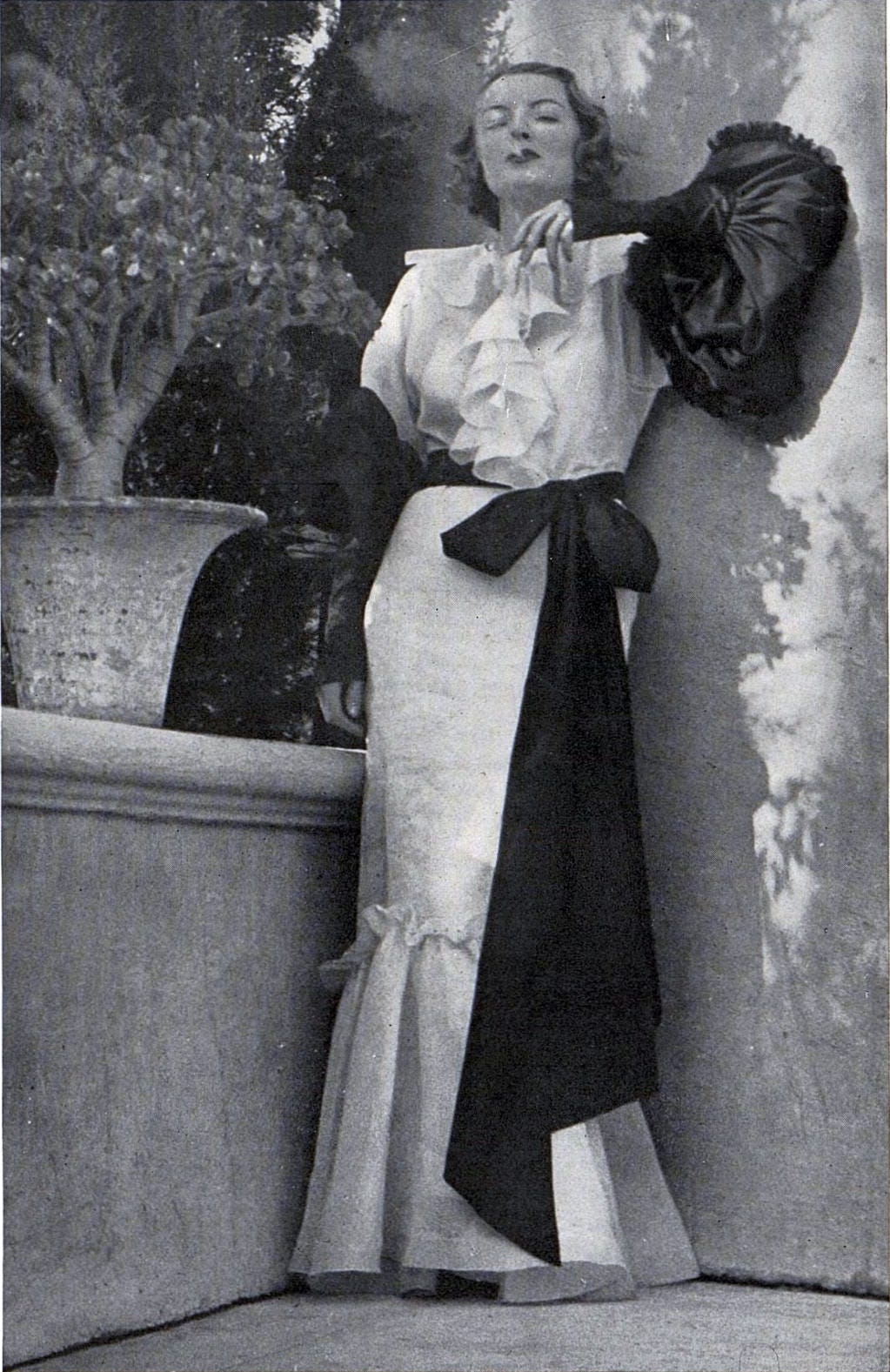

Harper’s Bazaar, February 1934; Text by Adrian and photos by Toni von Horn

I cannot see how any American woman can avoid the common sense of looking to America for her clothes. It is the most natural thing in the world. American designers know her life, and the way she wants to dress for it. They have stretched on her beaches, danced at her country clubs, sailed in her boats, met the men she is out to capture. More important still, they know and understand her peculiarly American attitude toward dress.

The American wants to look attractive, but she wants to arrive there by a short cut. She hasn't the time to concentrate on being visual all day long, as the French women do. She can't stand the exasperation of many fittings. She likes to be able to jump into a little dress and look charming without contributing anything herself but slim hips and a pretty face. She is more active than the Spanish and Italian woman. She doesn't understand the daytime dressiness of the German. She wants a fashion that she can put over quickly. She feels, quite rightly, that the subtle points of couture are lost on the average American man. The fresh white piqué bow (spring), the puff sleeves (cuteness), the feather cape (femininity), the long, slinky train (seduction)—these speak his language. It is only very recently that she has dared to come out openly and admit that she often actually prefers American dress. Prior to this year, even six months ago, she was apologizing for her American clothes on the grounds of the depression. The only bit of Americana that she ever vaunted was the native blue jeans of Wyoming.

Her change of view-point has been brought about very largely by the movies. The movies have popularized American design as nothing else could do. In New York, on a first night, in one motion-picture theatre alone, five or six thousand see a new gown launched. For purely mechanical reasons we have to launch rather than merely reflect fashion. Aside from the fact that I would get no pleasure from copying French clothes, I cannot afford to do it. A month after a French gown is shown in New York, or published in your magazine, the copies begin to flood the land. Our pictures are not released until three or four months after they are started. If I took a dress already popular, and copied it in a picture, ladies in the audience might already be wearing copies of it and the whole film would appear to them passé.

When sound came in, a great change came over the movie fashions. With the entrance of the human voice actresses suddenly became human beings. A quality of mind came into the characterization and the story. Everything had to be more real. Roses became real roses, Chippendale chairs real Chippendale. The clothes took on a genuine character. You remember how Ziegfeld used to make his show girls wear silk underwear so that they themselves would feel the glamour they were to put across.

We have carried his theory to the nth degree. Our stars wear imported fabrics, Linton tweeds, fine hand embroidery. When we want to say splendor we do not count the cost. The court costumes that I made for Garbo in Queen Christina are a good example. That embroidery, which you heard rustling as she moved, was real embroidery worked from an ancient stitch. I had Mexican and Polish women working for months on it and it cost over $1800, but it gave Garbo a sense of rightness and the film conviction as nothing else could have done.

The new quality of reality in movie clothes was quickly felt by women in the audience. They began to picture themselves in the charming tea dresses of Shearer, the puff sleeves of Crawford, the exotic head-dresses of Garbo. The first time I became conscious of the terrific power of the movies was some months after Letty Lynton was released. I came to New York and found that every one was talking about the Letty Lynton dress. I had to go to the shops to discover that of all the clothes I had done for Crawford in that film, it was a white organdie dress, with big puffed sleeves, that made the success. In the studio we thought the dress was amusing but a trifle extreme. The copies of it made the original Letty Lynton look very modest and shy, which proves a fact I have long suspected, namely that the movies are giving the American woman much more courage in her dress and a much more dramatic approach to the whole subject of clothes.

AMERICAN design has been greatly held back by lack of recognition from American women. For every pat on the back which the fashion magazines have given us we have been enormously grateful. The creation of fashion is not easy work. It is not just a casual kind of enthusiasm, it comes from a perpetual finger on the ever-beating pulse of fashion, and more and more clever young Americans are studying that heart-beat and discovering for themselves what Paris, a much older doctor, has studied for years. I do not in any way mean to imply that France is not still the center of creation. She has been a nation too instilled with the traditions of centuries to be usurped as the most vital fashion source. No one who has ever gone behind scenes in the dressmaking business there fails to recognize the exquisite sense of color, line, and cut, and the eternal impish inventiveness and spontaneity that actuates every one down to the meanest fitter and buttonhole maker in those great dressmaking houses, and to wish that we had more of that god-given quality here.

But if any young designer is tortured by the hobgoblin idea that you can't create clothes away from Paris, let him come and breathe the air of Hollywood for a while. With good materials to work with and interesting subjects to work for, you could create on a desert island. As soon as the French fabrics land in this country they are rushed to us for inspection. They are an inspiration in themselves. As for subjects, the crystallization of all American types is here to inspire you, from the boop-a-doop girl to the sophisticated Garbo. Norma Shearer, the purely American woman with a dashing quality in her clothes; Joan Crawford, with her essentially American view-point full of American activity; Garbo, who is capable of carrying anything with terrific authority if it is interesting to her and fires her imagination, like the mad little pill-box hat I once did for her. For years we made high in front, low in back dresses with long gauntlet gloves for Garbo. She has always hated bare arms, so we had to make her comfortable. No one dreamed of copying these dresses at first. When Garbo walked into the room, it was Garbo the eccentric. Look back over the pictures of her four years ago and see how modern she looks, like a million smart American girls of today.

OFTEN the script itself gives me an idea. Eight months ago I worked on a picture in which Kay Francis played the wife of the mayor of a small town in Austria [Storm at Daybreak]. I thought it would be amusing to make her modern clothes with a peasant feeling. It seemed to me that being a very clever woman in the story, with a great sense of patriotism and love of her people, she would very likely have found it interesting to introduce some of the peasant quality into her sophisticated clothes. I adapted the full skirted idea to several coats and dresses. This amusing silhouette has great possibilities. You can see several developments of the idea in the clothes of Miss Harlow in The Blonde Bombshell.

There is undoubtedly a certain evolutionary quality in fashion. A very interesting example I have on record from some months back. We were doing the clothes for Diana Wynyard in Rasputin. The action took place in 1913, and we made those draped skirts that cling round the back of the ankles and drape to the front, sometimes with flaring tunics and over-skirts, "harem skirts" they called them in those days in Paris. Diana said she liked the dresses so much that she wanted to take them back to London. Then several months later we had to do a picture that showed the clothes of 1940. It is ridiculous to try to look ahead ten years, but I felt it would be fun to try an adaptation of the 1913 line. We made several of these dresses, and eight months later I had a lady journalist from Chicago pounding at my door to find out what it was all about. And then I began reading the fashion magazines and found that there was much talk of prewar fashions, that a prewar party had been given in Paris with every one in white broderie Anglaise. The prewar thing was in the air and everybody was tuning in.

WHAT else is in the air today? What is coming? I feel that we are tired of being clever at $14.50. I think that clothes are growing more important in every way, even a little bit grand. This depression has left us with a desire for a little more ritual and dignity in life. I think that there will be a revival of beautiful embroideries and fine laces. I think that tweeds will hang loosely again and not be padded and full of projection. In fact, I believe that there will be a reaction against the bulky and architectural era of clothes that we have just gone through.

Personally, I don't care for the off-the-face hats and believe they will pass. I think that more and more designers are going to discover, as I did, that the bias skirt, unless very carefully treated, is apt to enlarge the figure. We try to elongate the figure whenever possible, and when the waistline is high you always get the illusion of longer legs. For that reason I do not believe that the lowered waistline will return, for unless you are perfectly formed it has a tendency to make the figure look dumpy. As for hair, the simpler it is the better. I love to see hair entirely natural, as Norma Shearer is wearing hers, for instance—quite short, just well brushed and sort of healthy and crisp looking, without braids or any fantastic contraptions.

I think that we can do amusing things with natural color linen coats with black velvet collars. I want to try long organdie coats. I believe that those stiff white collars that I made for Garbo in Christina may be head-liners—sharp, white linen collars on dark dresses, which give the wearer the illusion of being beheaded. And, as I said before, I believe that the skirt of the dress of the 1913 era lends itself to a very graceful treatment.

The possibilities open to the designer are infinite. With a receptive, even a clamoring public ready to pounce on any new American talent, with the power of the movies here to promote dramatic ideas, the air of the American fashion world is teeming with excitement. But we are still pathetically poor in truly original and skilled designers. We are not so scholarly nor so light-hearted nor so courageous as the French. We have not learned how to be ga-ga in the grand manner. You cannot become a designer over night. The basis of all good design is courage with knowledge. Any one interested in becoming a fashion designer should make a complete study of the actual history of architecture and interior decoration, as well as of dress, because both are interwoven closely and give a store of important data and inspiration from which to draw.

Nor is great fame to be won by translating from the French. An artist who signed his name to a copy of a Gauguin would be booed out of the galleries by the critics. The cribber of Hemingway would be sued to bankruptcy by the copywriters. There seems to be no compunction about appropriating a shoulder or a hemline or a frill. If American design is to flower and go down in history, it must stand on its own feet. Otherwise, like the boom of the “modern” and “modernistique” furniture of five or six years ago, it will peter out and be remembered only as a lot of first-class ballyhoo.

Bombshell is certainly one of the best films of the 1930’s. Great article, thank you. All this years before “The Women”.