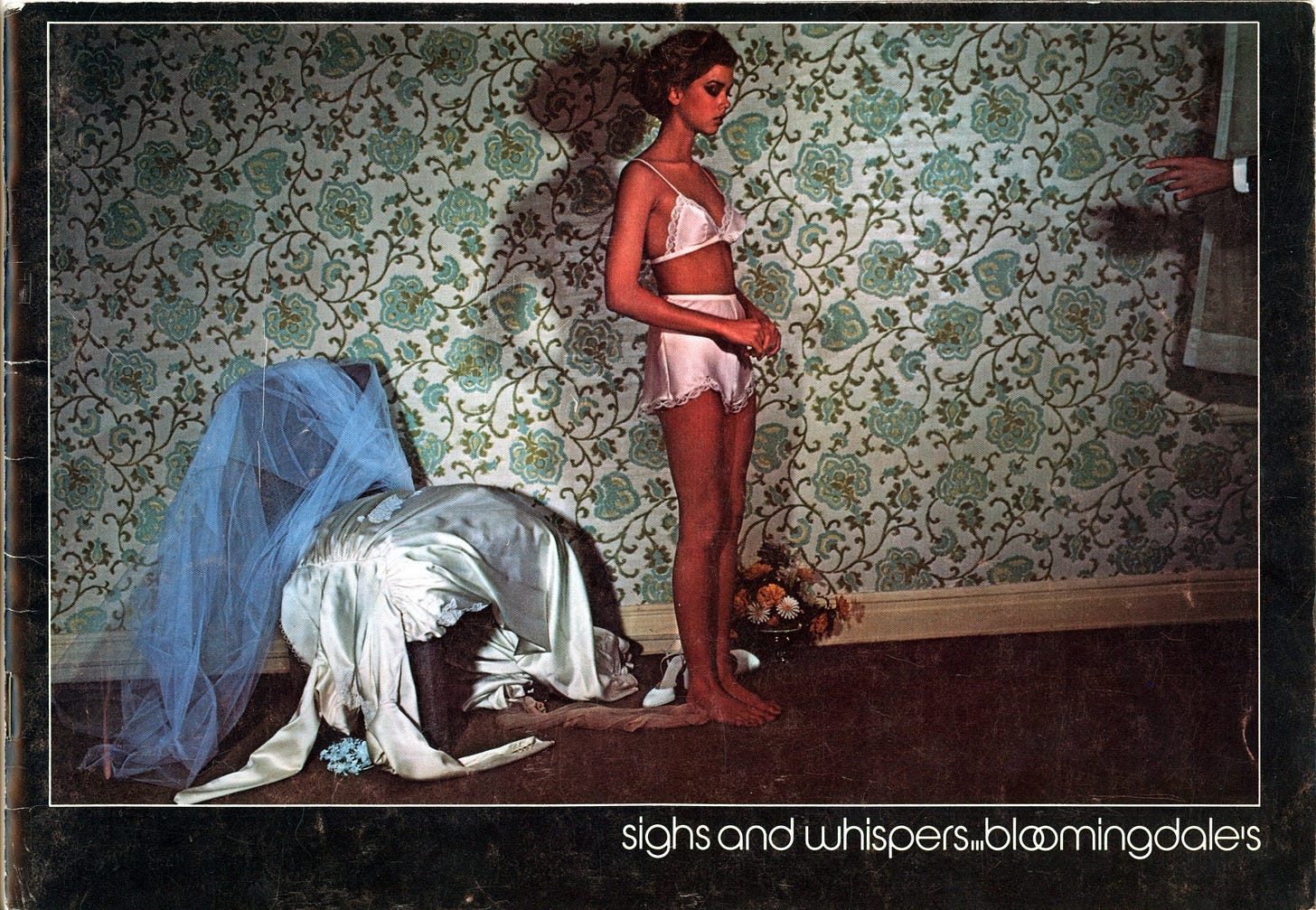

Nineteen years ago I saw an exhibition of Guy Bourdin’s work at the V & A in London. Though I already knew his work, seeing them elevated from the page to large dye transfer prints was a transcendent experience. As I was in photography school at the time, I was as beguiled by the artistry they revealed as by the fashion they sold. Several years later, when it came time to name a blog I was setting up on Blogspot, I opened up that show’s accompanying book—immersing myself once again in his work, I repeatedly circled the name of a catalogue Bourdin had photographed for Bloomingdale’s in 1976. “Sighs and Whispers.” I took the title of this lingerie catalogue for that blog, and fifteen years later again for my podcast and this newsletter. After all that time, I thought I would share the legend behind the making of the catalogue and tease out the likely reality of how this now highly collectible and expensive pamphlet came to be.

The year of its 75th birthday, 1947, Bloomingdale’s began the multi-decade process of shifting its merchandise and image from the mass-produced, lower-priced, and lower-middle-class to the upscale, affluent and elitist. It wasn’t that Bloomingdale’s wasn’t successful—in fact, their sales and earnings were at a record high. But the area around the store was changing—the city was changing—and the store needed to stay several steps ahead of where those urban population shifts might go. Bloomingdale’s president, James Schoff, and chairman, J. Edward Davidson, worked together to hire an executive team that would revolutionize retail; they also developed new merchandising objectives that were “so all-encompassing, and so radical, that they ultimately led to a complete change in [Bloomingdale’s] very essence.” First through elevating the home furnishings department through the fifties, then the store as a whole in the sixties through their annual import fairs, and finally with fashion in the late sixties, by the 1970s Bloomingdale’s was the hippest department store in New York and likely all of America. Everything that Bloomie’s did was an event, every product they picked up a guaranteed trend—all of fashion and retailing watched their every move.

With the store itself such a spectacle, most of their customers chose to visit in person to do their shopping. Mail and phone sales were a minimal part of the business—seasonal catalogues went out to selected charge customers who had ordered by mail before; catalogues were slipped into Sunday supplements to reach a larger audience; the biannual home furnishings sales were advertised in catalogue form. Overall, the Bloomingdale’s catalogue was a neglected form. In the early 1970s, vice president of communications Joan Glynn pursued a catalogue reevaluation and expansion. Though she left the company in 1974, Glynn had inspired some of her colleagues to understand the marketing power of a good one. Arthur Cohen, senior vice-president of marketing, began hiring major photographers to shoot catalogue photos that would transcend the normal strictures of the medium. In 1976, he ventured into totally new territory by hiring the French photographer Guy Bourdin—then known solely for his surrealistic ad campaigns for Charles Jourdan and fashion shoots for Vogue Paris.

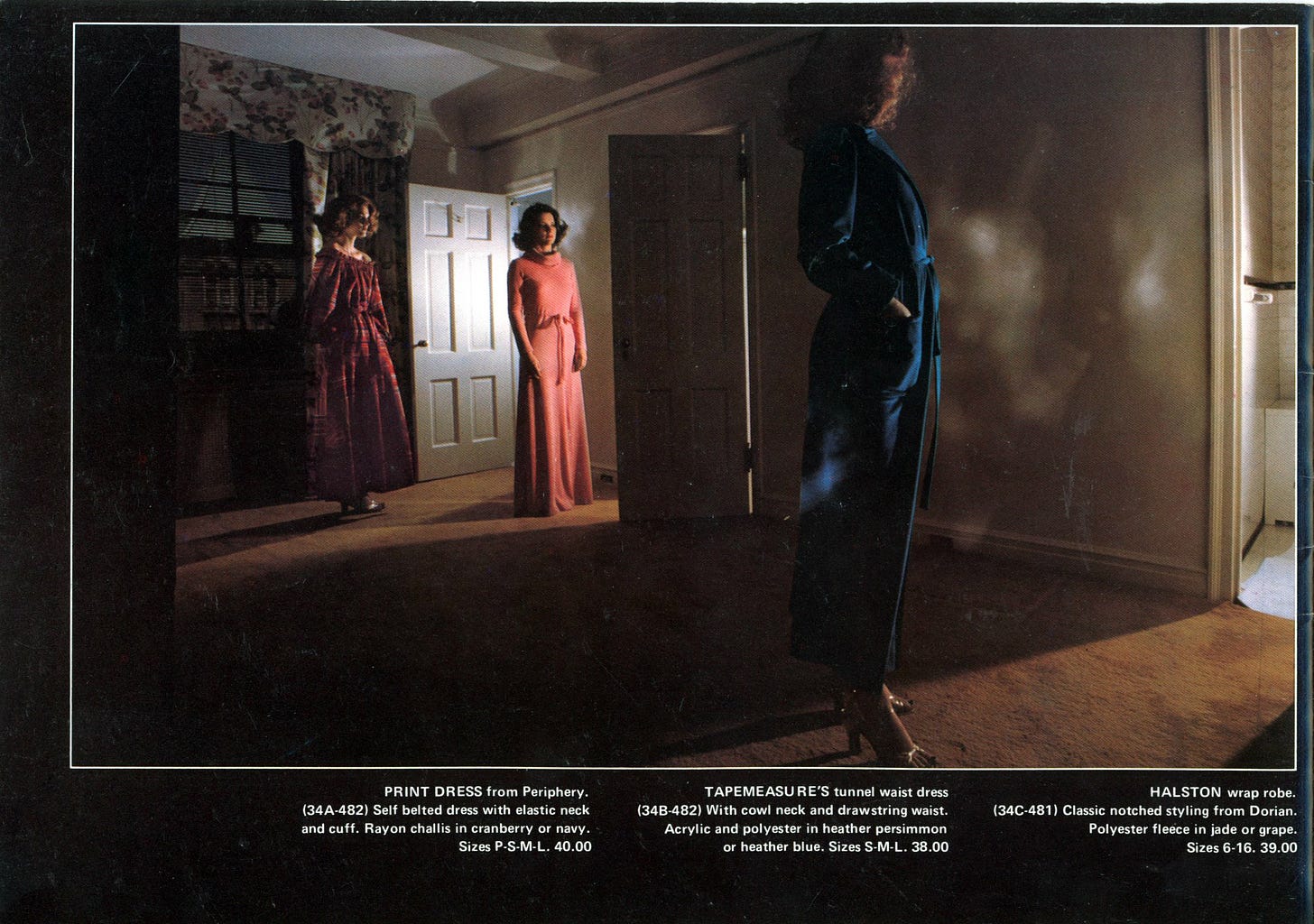

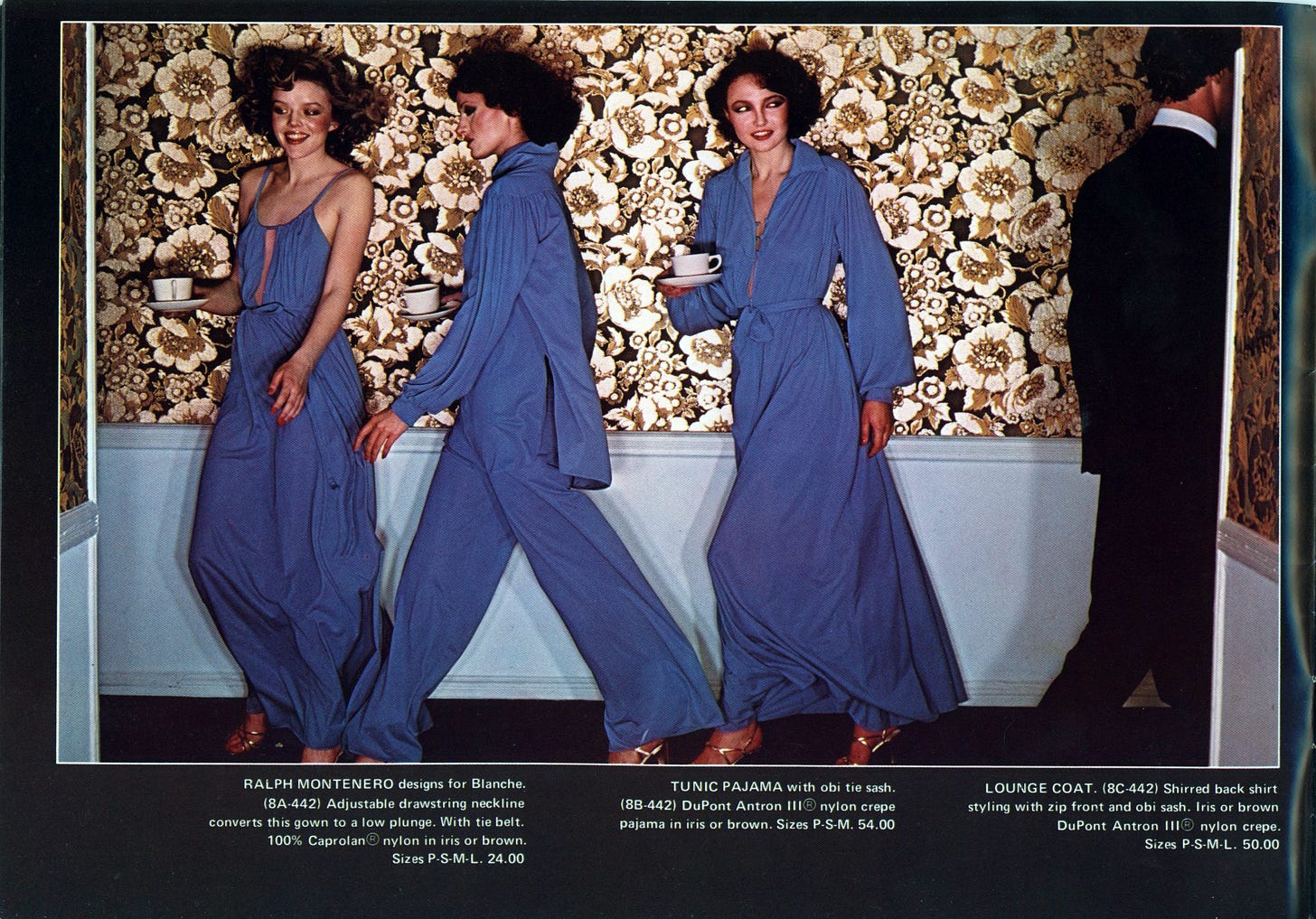

The legend as it was told by Bloomingdale’s staff to the press and in their own later recollections: When Bourdin arrived in New York, he invited sixty-five of the city’s most successful models to the store (or to his hotel) for a go-see. He took polaroids of each in the nude, before declaring that there were no beautiful models in New York. Surprising the Bloomingdale’s advertising staff, he announced that he would find his own models and left. Bourdin found six girls either at clubs or through NY-based European photographers. Over the next month, he shot the whole catalogue in complete secrecy, not allowing Bloomingdale’s to see any of the photos until the day he returned to Paris. They were so shocked by the images (which they themselves had requested be unlike catalogue photos) that they laid them out as if in an art book, not a catalogue. It was sent out to charge customers and slipped into the Sunday New York Times, and immediately became the center of controversy. Within a week of release, most major newspapers across age country had published some form of this story—usually concluding their piece with a statement like, “It is already being talked about as a collector’s item.”

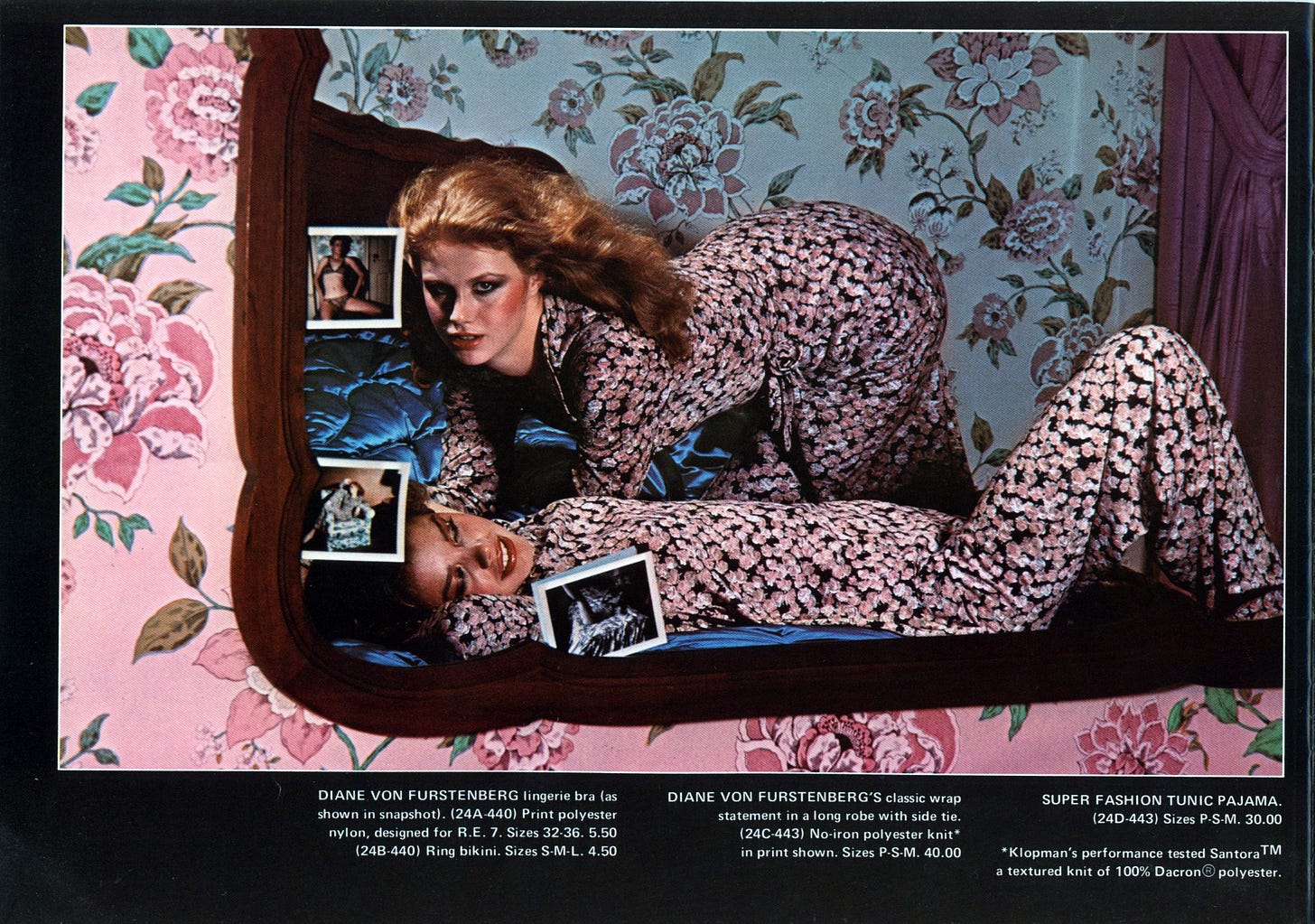

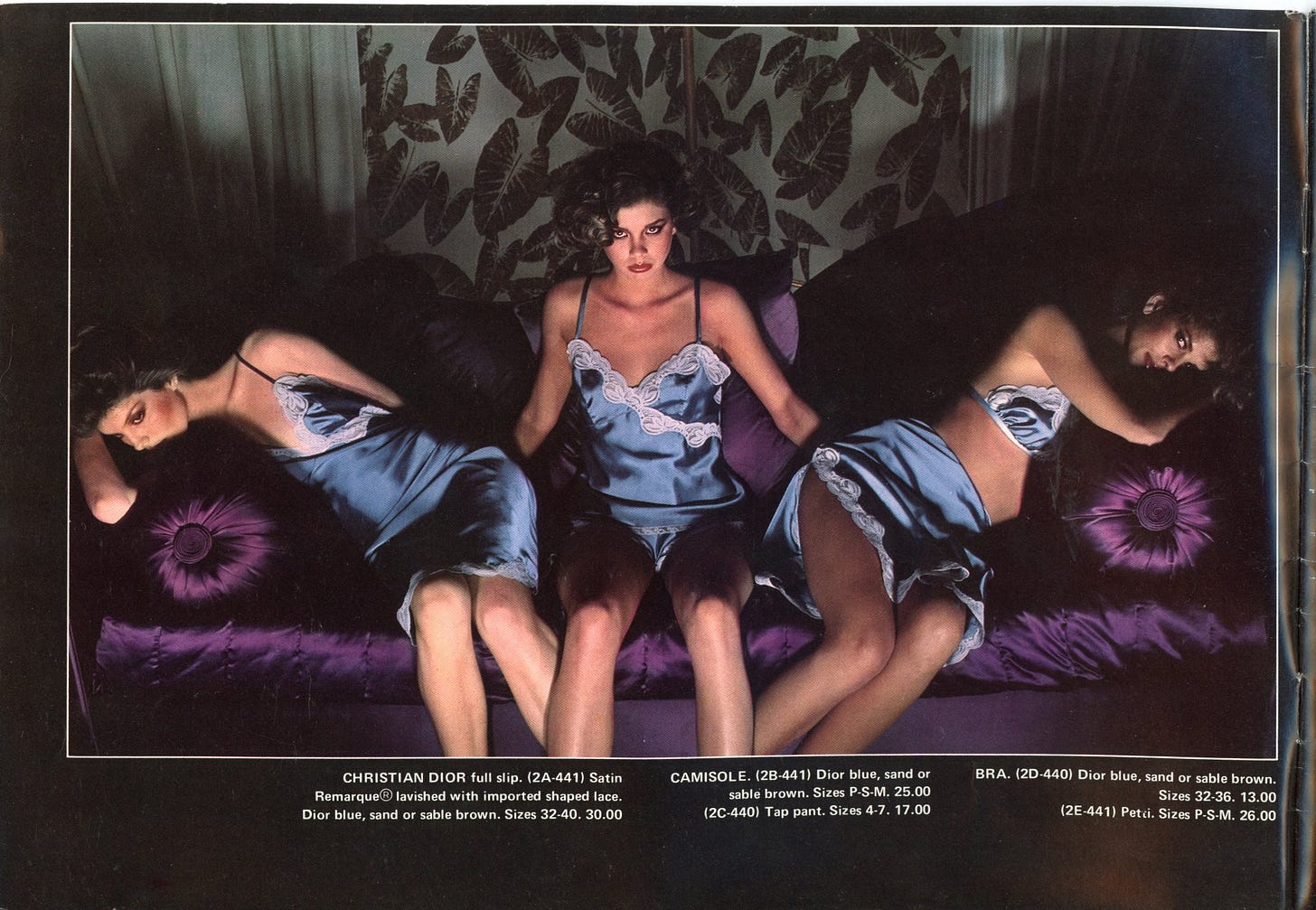

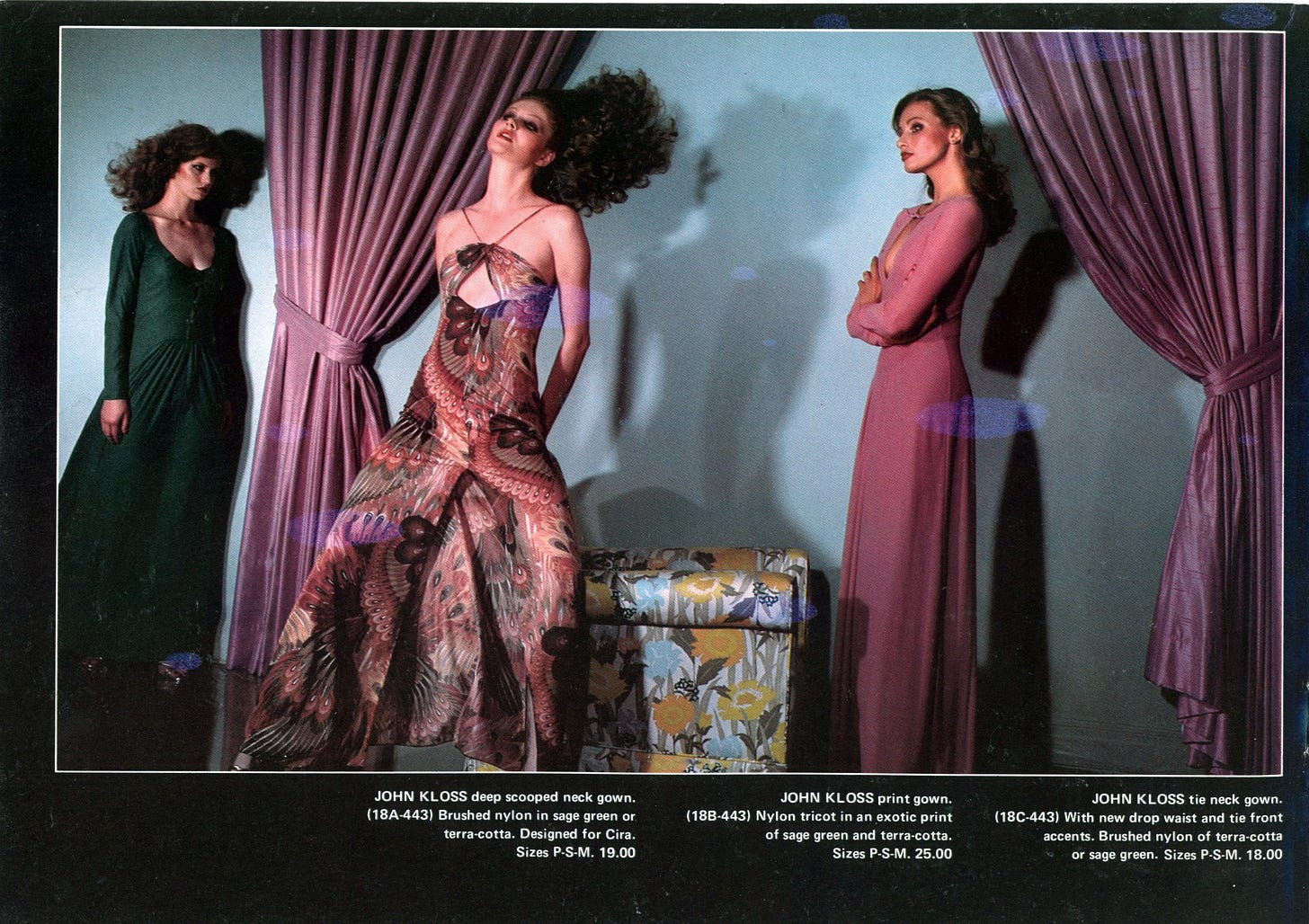

“To understand the furor over the catalogue, you must picture the pictures. The satin slips, see-through bras, and clinging gowns are all displayed in settings of the most artistic but suggestive nature. In one Bourdin vignette, three women clad in undies and smoldering looks sit on a sofa expectantly. In another, one woman stretches languorously in bed, while her female companion, wearing the same outfit, leans over her. The pictures are erotic, suggestive, brooding, exciting, super-charged, kinky and controversial. The big question is, will they sell lingerie?”

A marketing myth as finely thought-out as the catalogue itself, it isn’t difficult to reveal the lies in their story. Cohen specifically sought out Bourdin because of his surreal, erotic images—veiled with mystery and often sinister narratives. When shooting, Bourdin thought only about how it would work on the page of a magazine—he photographed to stop readers in their tracks, to shock and confront them (and hopefully sell them some shoes in the process). Bourdin’s work was only available in magazines—one had to track down issues if you wanted to see what he was up to, and everyone did since there was no one else like him. Cohen and Bloomingdale’s wanted that provocation—they wanted to grab the customer, make them intently look and wonder about the photos, then have them order a new bra and panties—just as they wanted that cult status and the press that came with it.

In both the recollections of Bloomingdale’s executives and in period newspaper reports, the models are all described as “unknowns.” A careful look through the images reveals Janice Dickinson and her younger sister Debbie, Appolonia Van Ravenstein, Lisa Taylor, Isabelle Weingarten, Rene Russo, Viviane Fauny, and Rita Tellone, along with several others that I have yet to name. These were not unknowns—though perhaps not the perky All-American beauties that Bloomingdale’s staff might have gathered first. American Vogue’s most-used models that year were the likes of fresh-faced blondes Patti Hansen, Rosie Vela, Anne Holbrook, and Lisa Taylor - the last who appears in two images in the catalogue. Any fashion journalist or even the most cursory reader of Vogue—i.e. the people that Bloomingdale’s wanted to appeal to—would recognize many of the models, which makes the promulgation of the “unknown” fallacy even odder. While the Dickinsons were not yet the supermodels they would become, both already had successful modeling careers. Fauny first appeared in Vogue in 1970, and since then had been shot multiple times by such luminaries as Irving Penn and Helmut Newton. Many of these girls were high-fashion cover girls, a fact that one would assume that the PR department and press would have leaned on. By recasting them as “unknowns,” it allowed Bloomingdale’s the space to spread a story of Bourdin as a tempestuous photographic tyrant set on doing whatever he needed (including picking up young girls) to achieve his artistic desires.

Books and articles also all state that there were solely six models—another declaration that can easily be disproven by simply looking at the women’s faces. Journalists and writers were so intent on describing the models as “snub-nosed, very young-looking… sloe-eyed Lolitas” that they failed to look at them. Even Rosetta Brooks, in her 2003 essay on the catalogue (building on one she wrote in 1982), calls them “lookalikes”—thus denying the models their individuality. She goes on to say that this denial is his goal: “But Bourdin’s use of lookalikes is calculated to make an immediate sexual response to his models even more remote. His netherworld of sexual enticement plays upon the ambiguity implied when sexual stereotypes of women are deployed for female consumption. Instead of presenting fashion models as real people whose individuality is asserted by the adoption of a fashion, Bourdin enhances the reduction of women to type.” I would counter that, though they have similarly heavy makeup and curled or slicked-down hair, the models are not identikit—he could have easily accomplished that by choosing a few similar brunettes or redheads, but instead he chose a full spectrum of different hair colors, fair shapes, and beauty types. If a viewer looks at the photos and sees only identical models with heavy makeup and thin bodies, then it is the viewer who is choosing not to see them as real people.

Once one realises that the facts about the models are incorrect, it casts all of the story under suspicion. Joan Kron wrote in New York magazine that “Bloomingdale’s executives in charge of the project have yet to recover from Bourdin’s requests.” Bourdin was repeatedly made out to be such a control freak—demanding other models, demanding complete freedom—that the idea that he simply gave Bloomie’s the photos without any discussion of their final form appears ludicrous. Whether you consider this a sign of a control freak or an artist who has worked hard to achieve a high level of respect, Bourdin was known for turning his photos into magazines with the layouts already mapped out. He photographed for the page, for the spread. It seems very unlikely that he would spend a month obsessively shooting to then run away. According to Bloomingdale’s then-president Marvin Traub, in his later 1993 book on the store, Bourdin’s contract “demanded complete autonomy: We would see the photos when he turned them in. He would deliver thirty-six photos for thirty-six pages, no reshoots.” He then goes on to say that Bloomingdale’s staff was so perturbed by the photos that they had to get a second opinion from Calvin Klein (he loved them).

As Bourdin had yet to publish a book (he never did during his lifetime) and was highly admired, Bloomingdale’s would have known going into this that anything he shot would be poured over and collected. Why not make it truly a collector’s piece through form, not just through context? The design of the catalogue—the black borders, the single photo per page—replicates that of an art book. Though early press stated this was Bloomie’s decision, it is clear that Bourdin gave them the images in sequence. He photographed these photos for the single page, not for double-page spreads; he shot them often in pairs, to be viewed facing each other. As an artist, Bourdin thought through all of this; he did not leave behind his negatives with zero guidance.

What does appear true is that for a month Bourdin, his girlfriend, his assistant and two dogs holed up in the Surrey Hotel, a residential apartment hotel on East 76th Street near Central Park. Many of the photos were taken there as Bourdin loved the wallpaper and interiors. He used several other locations throughout the city, all providing the strange placeless sense of place—a feeling that you’ve been in these rooms before, moved through these spaces yourself, but yet there is a disconnection, an unreality to them. Traub described it as looking like the models “lived together in some boarding school for wayward girls"; are they lovers, roommates, friends? More so, the images feel like moments caught without meaning, a narrative that is unknowable yet oddly resonant. In the words of an unknown AP journalist, “The mood is kinky. The models are tough. Farewell sweetness and apple pie.”

Regardless of the veracity of its origin story, the beauty of “Sighs and Whispers” continues to move me. The ambiguity of the narrative, the sensations of sensuality and horror, the glamour—I keep coming back to soak it all up, let it wash over and inspire me. As Rosetta Brooks wrote in 2003, “I still experience a sense of shock when I encounter the photographs of Guy Bourdin and other fashion photographers from the mid-1970s because their images continue to prove that advertising need not be an elaboration of a safe, prescribed fantasy: it can be a challenge. Their photographs suggest that given that the promises of advertising are clearly fake, it’s fair game to emphasize the falsity of the image and to challenge the threshold of our imaginary world. It was fashion at the brink…”

Further reading:

Brady, Maxine. Bloomingdale’s. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980.

Brooks, Rosetta. “Sighs and Whispers in Bloomingdale’s.” ZG, no. 3 (1982).

Brooks, Rosetta. “Sighs and Whispers.” In Guy Bourdin, edited by Charlotte Cotton and Shelly Verthime, 126-133. London: V & A Publications, 2003.

Stevens, Mark. “Like No Other Store in the World”: The Inside Story of Bloomingdale’s. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1979.

Traub, Marvin and Tom Teicholz. Like No Other Store… New York: Times Books, 1993

.