She-Wolves: The Untold History of Women on Wall Street

A Conversation with historian Paulina Bren

As I spend so much of my time thinking and writing about the 1960s and 70s, dress and women’s lives, feminism, and New York, it can sometimes feel like there is nothing left to learn about this little time in history—but then I come across a book that makes me realize just how narrow my focus has been. Paulina Bren’s new book, She-Wolves: The Untold History of Women on Wall Street, charts the story of those first women to venture into banking and onto the stock exchange in New York—rising from secretaries to clerks, from analysts to brokers, and beyond. Following the careers of a group of women—of different races, classes, and backgrounds, who achieve various levels of success in the industry—Bren creates an engaging story that clearly illustrates the hardships these women encountered trying to break into what was a closed man’s world. While all in NYC, they exist a world away from the fashion designers, feminists, and members of the counterculture I normally write about.

When I first saw a mention of She-Wolves, I immediately realized how little I knew about this subject and how little thought I’d ever given it. My father worked on Wall Street in the 1980s, and while I was very young at the time, I only remember hearing of one woman working alongside him (other than the secretaries)—it was completely accepted that it was a boy’s club. Reading She-Wolves allowed me to understand what a woman would have gone through had she joined my dad’s investment bank in the 1980s or a brokerage firm in the 1960s.

As we discuss below, nothing has been written on the women of Wall Street before—their names and stories, no matter how revolutionary, are little known beyond the people they worked with. For all the breakthroughs and firsts that Bren lays out, it is also a story of sexism and misogyny, barriers and harassment. As Wall Street changed from a “provincial, almost quaint little enclave” into a cultural, financial behemoth known worldwide, so did the opportunities available to women evolve—as did the appropriate dress for a female worker there.

Paulina Bren is a historian and teaches at Vassar College, where she is the Adjunct Professor of Multidisciplinary Studies on the Pittsburgh Endowment Chair in the Humanities, and the director of the Women, Feminist, and Queer Studies Program. Previously, she has published academic books on life behind the Iron Curtain and more recently, the 2021 bestseller The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free.

I spoke with Paulina last week about the research and writing process for She-Wolves, her background as a historian, what led her to look at women on Wall Street, their dress, and much more. She-Wolves is now available on Bookshop, Amazon, and wherever books are sold.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Laura McLaws Helms: I really enjoyed your book. I knew about the cultural context of Wall Street and New York in the mid-twentieth century, but none of the specifics of how women came to work there. I looked around, and nothing seems to have been written about this subject before.

Paulina Bren: Nothing. That's the crazy thing. Honestly, I went at this the same way. I'm a writer. I write histories and so forth. I didn't know anything about the finance world. When I started to realize that there's nothing out there, and in fact, when something is, such as this oral history archive at the New York Historical Society, where it's like 55 oral histories they did 10 years ago, five of them are women—not so surprising, frankly.

What's surprising is that the men, when they were asked, "Well, what about the women?" They were like, "What women?" Or, "Well, there really weren't any women," or, "The women weren't qualified, so I couldn't hire them." I started to realize if we leave that story to the men who are on Wall Street, there'll never be a story, there'll never be a history. I had the same feeling. It came as a surprise to me all of this as well. I'm glad to hear it came as a surprise to you.

Laura: My dad was on Wall Street in the '80s. When I first saw something about your book, I realized that I only remember ever hearing about one woman other than the secretary. This one woman, she worked under my father and they're still friends four decades later, but that's the only woman I ever heard about. It was accepted that the women around were secretaries or wives.

Paulina: Yes, exactly. Even when that started to shift in the '80s, obviously the residue was there. It still is.

Laura: How did you become a historian? Why history?

Paulina: I went to Wesleyan University, and I wanted to be a novelist, a fiction writer. For my senior thesis, I actually did a book of short stories. I won the fiction prize. Long story, of course, because of a boyfriend, ended up in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I took a job as a cashier in a wine and cheese sort of liquor store in Somerville while I was writing my first novel.

I had this finished novel, which was still rough, but I actually got this really huge agent to represent the book. It was sent out, and it was always almost there, almost there. While this was happening, I panicked because I was, what, 23? I felt like I had nothing on my CV. The Berlin Wall had just come down, and I can speak Czech. I was like, "I'm going to apply to graduate programs, but I'll just keep writing secretly." I got a full fellowship to do a master's program at the University of Washington, Seattle, had no idea where Seattle was, and I went.

My plan was that I would just keep writing fiction, but I got suckered into it. Because ultimately, being a historian you have to stick to research, but you're telling a story. It's very similar. That's how I became a historian. Actually, now I'm going back to fiction writing a bit.

I focused on Eastern Europe behind the Iron Curtain when I was in graduate school for European history. We basically stopped at 1968. We didn't know anything about the '70s or '80s. It just wasn't taught. Part of it was because there were so few books about it. When I went off to do my dissertation, I decided I wanted to write about the '70s and '80s in Czechoslovakia; in a sense, the decades that if my parents hadn't fled with me and my sister after the Soviet invasion, I would have lived those decades there, but I didn't. I wrote [The Greengrocer and His TV: The Culture of Communism After the 1968 Prague Spring] and did very well. Then I co-edited another book on communism and cultural histories of communism [Communism Unwrapped: Consumption in Cold War Eastern Europe].

Then I felt like I was done. I'd said what I wanted to say, and that fiction writer part of me just wanted to write books that people really read that are page-turners, but they're history. I already had a track record, got myself an agent, and The Barbizon was the first attempt at that and did really well. In a sense, this is a follow-up to The Barbizon. The Barbizon was about the history of this women's only residential hotel in New York on the Upper East Side, and it tells a story of New York and the women who came there and how they embodied New York at that time, particularly in the 1950s. She-Wolves tells the story of these women in the '70s, '80s, and '90s in New York. I really see it as a second part of potentially a trilogy.

Laura: It makes sense that the early part of your background is in fiction because this is a narrative nonfiction versus a more academic book.

Paulina: Right, I did what they call an academia crossover. I've stopped writing academic books and now write books that appeal to a larger audience. I love it.

Laura: I love both—writing, personally, both, but as for reading, this is just easy to read, it's really fun. How did you come across the idea for She-Wolves?

Paulina: In a sense, I really was thinking, okay, so The Barbizon woman really did embody the 1950s. Who's coming along in the '70s? I was really eager to write about the '70s because it's such an interesting time, not much written about it. It's the moment where New York goes from that glamorous 1950s Barbizon look and feel to the gritty, urine-stained, graffitied New York. I was really curious about it. Especially because at that moment, when you would think that the occupancy rates at the Barbizon would shoot up—women would want the safety, they'd want all of that that the Barbizon offered—but in fact, they were plummeting.

I was thinking, this is a different kind of phenomenon, different kind of woman, both figuratively and literally. Because one of my characters literally arrives in New York, goes to the Barbizon, and then leaves the Barbizon and heads to Wall Street. I follow these women out onto Wall Street. I'm really interested in spaces and places and the women who embody those and walk through those, inhabit them, and the larger picture and story that draws for us.

I found Wall Street to be really fascinating in how it has developed. We have this image of Wall Street in our heads now but starting in the '50s and the '60s, Wall Street is still such a sort of provincial, almost quaint little enclave on the southern tip of New York. People don't go there. You still have the Fulton Fish Market—the smell of fish wafting there. You still have the coffee roasters; they haven't moved to Dumbo yet. You have just this interesting space that very few people are going to.

In those days also, if you said you worked on Wall Street, you really worked on Wall Street or the streets surrounding it. Because now, obviously it's so spread out and later a lot of firms are moving to Midtown and so forth. This is a time, at the very beginning of my story, where it's a world unto itself. Also, what's particularly key, and it's key in terms of why women are able to jam that foot through the door, is because the streets of the Wall Street area are littered with these small brokerage houses. They're small, they're partnerships, it's just a handful of partners who make all the decisions.

On the one hand, that can work against women. They can simply decide, “We're not going to hire women and that's that.” They can make that choice. On the other hand, women cost a lot less. They would hire a woman to come in as a secretary, receptionist or clerk. They saw some talent, and women could multitask; they could do multiple things at the same time. Often, women stumbled onto Wall Street as they were looking for secretarial jobs. In those days, that's what you could do: you could be a nurse, a teacher, or a secretary. Those secretarial jobs on Wall Street paid more than elsewhere. They stumble into and then they start to look around, and some of them start to very slowly climb that ladder.

Laura: How did you go about tracking down and finding the women to profile?

Paulina: Oh, my goodness, I thought when I was researching The Barbizon it was so difficult. I later learned lots of people started trying to write that book and gave up because there were so few sources. I already knew, even if you're writing about pretty contemporary history, if you're writing about women, it's really hard to find sources. I knew that, but I had no idea just how hard it would be for these Wall Street women. It's astonishing.

Just to give you an example. There's a really great book that came out in 2005 by Eric Weiner [What Goes Up: The Uncensored History of Modern Wall Street as Told by the Bankers, Brokers, CEOs, and Scoundrels Who Made It Happen], which is a history of modern Wall Street, so the ups and downs told through multiple dispersed interviews of the men and women who were on Wall Street. It's 503 pages. 501 pages are men, and 2 pages is an interview with a woman. Of course, who's the interview with? It's the most famous, the only known name on Wall Street: Muriel “Mickie” Siebert. That gives you a sense of it.

The women I have in the book, they come from all sorts of backgrounds, and they reached different rungs of that ladder. Some of the ones that really were big names on Wall Street, shockingly, when you Google their names, you don't find anything. That was both motivation as well as a shocker. I say this to all women, "Put your story down somewhere. Somewhere. Please tell your story. Us writers and historians will be so happy in the future."

I was fortunate in that, as I mentioned earlier, the New York Historical Society has an oral history archive called “Remembering Wall Street, 1950 to 1980”—around 55 oral histories that were done about 10 years ago: 50 men, 5 women. Three of those women I ended up using. I, of course, went and I met with them, and I re-interviewed them, but the fact that they were these extensive oral interviews gave me a starting point. I knew at least who to go to. Then another woman, Marianne Spraggins, also did a life history with a database that does oral interviews of significant African Americans in America [The History Makers]. I'm so grateful that those four interviews existed because it was a starting point for me. Then I was able to contact them and go from there.

I did all sorts of things. If I found some little interviews somewhere with a woman, I would contact her, so I also did lots of interviews. Then as I also learned writing The Barbizon, it's my job to figure out the story, but you still need to talk to people who have some sense of how to narrate their lives, who understand what was important. That always means that you might interview a lot of people, but the characters I choose tend to be those who understand certain key things about their experience that I can then link with other women's.

Laura: I enjoyed following the women through the story as their lives change and as they come up against the adversity of sexism and the system. Also, at the same time, learning about the changing industry.

As someone who has never understood any of the stock market, there are times I had to reread a whole paragraph over and over again to be like, "Okay, what is this that these women are doing?"

Paulina: Readers have told me that it's a really painless way of actually learning about Wall Street and what they do on it. I was very mindful of that because I knew there'd be people reading this who didn't know what on earth takes place there. Frankly, most of us don't know if we're not in finance. It's really a vehicle to, once and for all, have some grasp of it, right?

Laura: Yes, and the way that they do the work is so different now than it was in the '50s or '60s. When you're explaining about after 9/11, and there's the woman who's like, "Oh, we're the last generation who can do it with pen and paper”—it's so crazy to me that you could even do that math, especially when it was fractions.

Paulina: It’s astonishing what they did without computers. Of course, that's why also there was sort of the paper deluge crisis. This is in the '60s. As the market is speeding up, they just have paper. That's all they have, and there are piles of paper. These small firms are going bankrupt because the backroom people are not filing the paper fast enough, and so you're still liable for that stock that somebody bought that was never filed, you're still liable for how that stock did. If it did really well, you owe those people money. This was happening to these small firms.

Yes, it's just all these things we don't think about, right? The ticker tape. The fact that everybody had this machine or the pneumatic tubes in the New York Stock Exchange that would deliver stock prices and so forth. Of course, for the first woman who actually traded on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange in 1976, as I write, Alice Jarcho, she was delivered dildos through those pneumatic tubes. Yes, it's just this crazy, disturbing, fascinating world you can't look away from.

Laura: Were there any things that were really surprising that you came across or that you hadn't considered?

Paulina: When I started the research, the women would say something to me, and I'd say, "Okay, now could you please explain that as if you were talking to a five-year-old?" I wasn't just doing that for myself, although I certainly was, but so I made sure I really understood it, but I also knew I wanted to translate it that way for readers.

I went into this, as I say, not wanting to have preconceptions. For example, I never asked the women their politics. I think they could guess mine pretty easily, but I never asked theirs.

The one thing I did know, of course, was that there's significant sexual harassment on Wall Street. It was a place that didn't even experience the #MeToo movement. I knew that, but I didn't want to write a book just about sexual harassment and inequality. That’s also why it's so important to look at a story that's over 50 years, because, no, this is not a triumphant account at all, but it's complex and you see its incredible complexity. That's also why I wasn't going to write just about sexual harassment, but it's part of the story.

Honestly, as jaded as I am, I was shocked by some of the things that happened to these women. What I also hadn't realized was their level of isolation and quite physical isolation. Of course, that made, at the beginning, sexual harassment that much easier. Often, it was a case of an entire office of men, a few secretaries, and then one woman who was beyond the secretarial pool. It was a very lonely existence.

The Financial Women's Association, which was started in 1954 by the very first several women who were outside of the secretarial pool—it was supposed to be sort of a matching kind of networking organization, as the men had lots of them, but it was, frankly, also so that they'd have somebody to have lunch with. Just to be able to go out there and have lunch. The sense of isolation, the dogged obstacles and harassment.

Muriel Siebert was the first woman to purchase a seat on the New York Stock Exchange in 1967. She had the seat at the beginning of 1968. She knew at the time, she said publicly, “I'm not going to go trade on the floor myself. I'll hire somebody to do that because I don't need to make more enemies.” It's not until 1976 that Alice Jarcho, who did that rise from secretary to trading assistant to trader, gets persuaded by somebody at Oppenheimer, she has a bit of a crush on him. He has an advantage in persuading her to go and be the floor broker for Oppenheimer on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. She really resists because she knows it's not going to be easy. It's never happened. There's never been a woman there. There are women clerks, but there's nobody who's really trading or at all, no woman who's trading. She finally gets persuaded. She goes on the floor. The press is there because it's a big deal. She slips on some paper, falls flat on her bottom. She has nasty things left in her booth whenever she returns, and of course everybody's watching to see how she'll react. She gets anonymous phone calls at one point and has to have a police escort to bring her in in the mornings.

She was there for four years. She knew it was going to be bad, but she hadn't realized to what extent she was disrupting tradition. New York Stock Exchange was created in 1792. 1976, the first woman shows up to trade. She hadn't realized how much she was disrupting. Alice thought once she was there, she'd established herself, that the harassment would let up, and it didn't. It would rotate and come from different quarters. Once she was very respected as a floor broker, the higher-ups, the specialists, they had to respect her. They needed her trades, so they no longer harassed her. Then it was the clerks, those guys, who were doing that, other more low-level brokers.

I think this is what shocked me the most. One likes to think that if you're there and you prove yourself, that if you're in an environment where people get used to you, that things will improve. A lot of times, it wasn't just for Alice, things did not improve. You had to learn to live with it. You had to have a thick skin.

Laura: Was there anything too shocking to put in the book?

Paulina: I'm sure so much worse happened than the women were willing to tell me. The fact that they were even willing to tell me is in itself completely shocking. Because what I also discovered, this is a world of secrets. The women who have persevered and who didn't just say, "I've had it. I'm leaving," those who stayed and really climbed the ladder, their legacy is also on the line, so they won't speak.

Susan Antilla—she wrote Tales From the Boom-Boom Room: The Landmark Legal Battles That Exposed Wall Street’s Shocking Culture of Sexual Harassment, she writes about sexual harassment on Wall Street and inequality. That's her main focus. She told me a story of how when the Boom-Boom Room came out, somebody did a dinner party where she introduced her book, and there were these women from Wall Street, and this very top Wall Street woman bent her ear for an hour telling her these horrific stories, just horrific. A couple of months later, she was at another dinner party and there was this woman, and they were going around the table talking about what's happened to them, their experience, and it's both men and women. It comes to this woman who had bent her ear for an hour, and this woman said, "Oh, nothing. It's been great for me. Nothing bad has ever happened."

This is not unusual at all. It's not a surprise that a lot of the women in my book, they worked at Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns. Both those firms were huge and they went bankrupt in 2008 during the Great Recession. The fact that they aren't around anymore made it much easier to talk about these things. Did a lot worse happen? Absolutely, but they are unwilling to talk about it.

Marlene Jupiter at the end—her story is much larger and more complex, but I decided to narrow it down because it was just a legal issue. It would be pretty easy to identify the players. She hit a point where, as she says, this leader of this wolf pack went after her for years and years and years. The level of anxiety, just walking into the office every day, and then finally having to bring an arbitration case against them. As I write in the book, if you sign off on [an arbitration agreement] when you work on Wall Street, you can't take anybody to court. It can only be as a class action suit, so that'd be a lot of you. As an individual, you're forced to go behind closed-door arbitration, where the judges are almost always… they've done studies on this, that the majority are old white men, and they're going to decide on whether they think that you've been sexually harassed or treated unequally. There are so many layers to the secrecy and it's in everybody's interest to keep it quiet, the women's too.

Laura: Do you think these women considered themselves feminists, as if they were breaking glass ceilings?

Paulina: I can answer that very easily. No. Again, just like politics, I didn't ever say, "Are you a feminist?" But it came up, and often they made a point of explaining to me that they're not feminists. It's so difficult because of course, what they're coming up against, what they've experienced, what they want is all a feminist agenda, but it is such a dirty word in that world that simply none of them will identify as that.

Laura: Yes, I was wondering that. There was one person you mentioned, I think they just came up just once, but they had moved to New York and were part of NOW [National Organization for Women] and the National Gay Task Force. The fact that this one person got these specific mentions, and then everyone else just exists within the boys' club of Wall Street…

Paulina: Yes, and [Nina Hayes] is the one who came to New York with experience, having worked for a small brokerage firm in Cincinnati. She came to New York because she wanted to experience feminism. She wanted to experience the gay liberation movement. She's the one who also came to the Barbizon and then left and headed off to rent an apartment once she had a nice job on Wall Street. She was on Wall Street because that was her qualification. It allowed her to leave the Barbizon and rent an apartment, but she was unusual in that sense.

Certainly, in the '70s, this is when the women's movement is really going strong. By the '80s, when Wall Street changes drastically, explodes in 1981 in terms of the number of people, and the fact that it's the place to be. Before, it wasn't the place to be. It begins to define our cultural values, not just our finances. This is a new wave of women. They're not the scrappy, hard-skinned women who were coming in the '50s, '60s, '70s, a lot of them from the outer boroughs, a lot of them college dropouts, who precisely because of their experiences and background can navigate in a particularly, I think, effective way.

These now, starting in the early '80s, are very different women. They're the women with MBAs. They are the women from Ivy League colleges. In the '80s, if you're graduating from a top college, over 50% of the class is going to Wall Street or finance in some shape or form. There's this Reagan revolution taking place, and people are participating in a way that having even graduated from college in the late '80s, I hadn't even realized this because that's not where I was and that's not where my friends were. I hadn't realized statistically just how remarkable it was, this revolution that was taking place.

These women who were coming, interestingly, I think they are more reluctant to say they're feminists, even as they see themselves as the beneficiaries of the women's movement—they think it's done. They don't need to call themselves feminists anymore. Then of course, they encounter that, okay, so now getting your foot in the door, getting into a prestigious trainee program, that's not so difficult, but wait, as you start to climb, it's just as bad. There are different waves coming with very different mindsets and expectations.

Laura: It seems like through all these generations of women, it's very clear that they're not supposed to have a career and children.

Paulina: Yes, the women in the '60s and '70s, for the most part realized that it's either family or career. You can't do both. Women coming in the '80s and '90s want both. They start to be able to eke out maternity leave, though it is disability leave, really. As one woman says, at the same time, just looking around the trading room where she is in Bear Stearns, the men, they have photos of their offspring, of showing how fertile they are and so forth. The women with kids, they won't put photos on their desks because they don't want to be seen as mothers because that'll take away from their power on the trading floor. Even though they found a way to have children, they actually felt like they have to hide them.

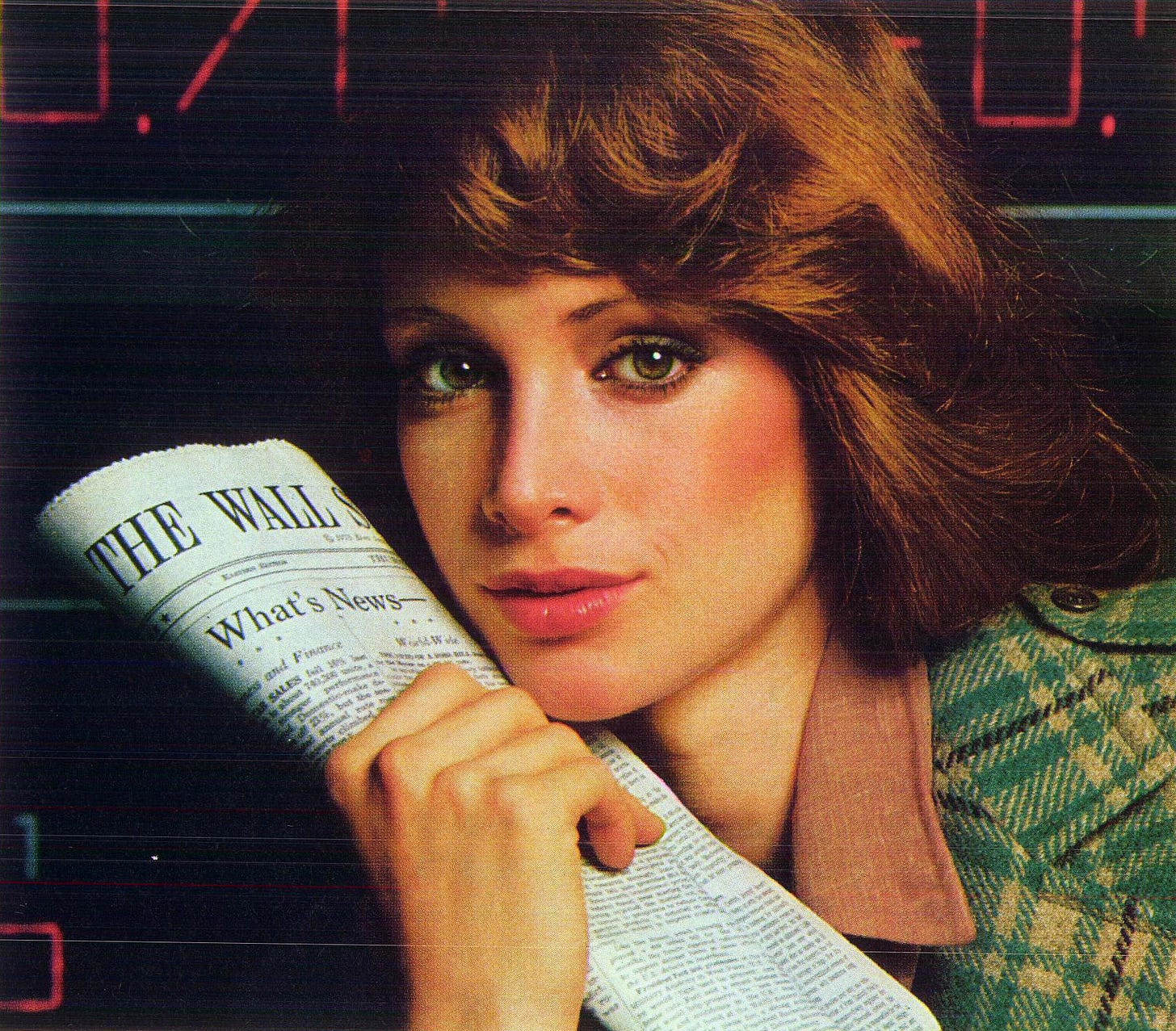

Laura: Throughout the book, you weave in and describe the dress, the clothes that they're wearing. Was this something that you specifically asked about?

Paulina: I asked every single woman what she wore. Most people can't remember what they wear, which I understand. Certainly, some women did, such as the women who, as she called them, wore her hooker boots that laced up past the knee. Those who were there in the '60s and '70s did often tell me about how confused they were on what to wear once they went above the role of secretary. In those days, now we don't really think about it, but what did business attire mean for a woman? They just had no idea, and so they'd come in all sorts of outfits as they thought, "Well, maybe this is appropriate." Also, these women, as I said, they're scrappy. They're from working-class, lower-middle-class backgrounds. They have not had to perform in this more rarefied finance world, so they really can't even rely on that kind of knowledge.

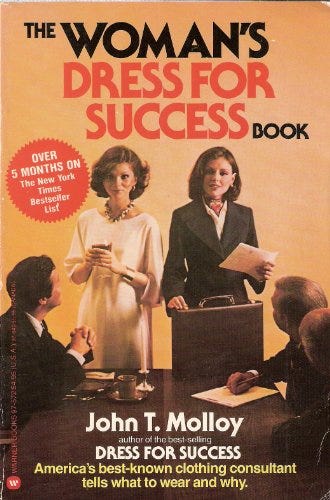

It's no accident that, as I write, in 1977, John Molloy, this guy who called himself a wardrobe engineer because he saw it as a science, he comes out with this book The Woman's Dress for Success Book, and every woman had a copy of this. It was such a bestseller. It's to fill this gap. It's a pretty strict, like “I'm giving you your marching orders” guide to how women should dress. Some reviewers really critiqued it because it was so hardcore, but women loved it because they didn't know how to dress. He had all these things like “You don't wear a polyester pantsuit because that makes you look cheap. You have to wear a certain kind of jacket, so it covers your breasts, so it doesn't show a tight outline of your breasts. You don't use a Bic pen. You buy a proper fountain pen.” All these things. He talked a lot about class, and it really was about passing. It was about passing as somebody who's upper-middle-class or upper-class when you're not. That was part of the whole shtick. It was fascinating.

Then of course, in the '80s, you have now women who are competing or think they're competing on a fairly level surface with men. They want to show they're also the testosterone alphas, and so they have the power suits with the big football shoulders.

Absolutely, the dress says so much about it. It was a delicious part of it in some ways to me because it does really speak to the initial confusion. Then it speaks to how to visualize equality, even if it's not there. Then in the '90s, it starts to get more casual, but more luxe. It's the Donna Karan. Yes, it's fascinating. I was always trying to pull more of that out of these women.

No Nonsense Pantyhose commercial, featuring financial analyst Elaine Garzarelli, who found fame in 1987 for correctly predicting Black Monday:

Laura: Did any of them show you photos of themselves?

Paulina: No. Back in those days, no cell phones, so nobody was taking pictures the way they do now. I would always ask, so sometimes I'd get snapshots, and I'd get the feathered hair and all of that, but there are very few snapshots. It's, again, a missed opportunity. Take pictures and write your life story, everybody.

Laura: That’s interesting. There are some photos in the book and that was great to see. When you'd mention somebody, I would often Google and as you mentioned earlier, there usually wasn’t anything, and often the only thing that would come up would be an article that you wrote for The Wall Street Journal.

Paulina: Yes, exactly. After The Wall Street Journal article, and I've had excerpts elsewhere in the UK and Ireland, when people read them, they'll even write to me and be like, "Oh my God, Beth Dater was such a big deal. Oh, my goodness." Yes. Well, yes, she was. Why is she nowhere on the internet other than my book or my articles?

Beth Dater is one of the panelists on this episode of Wall $treet Week, a PBS TV show that Bren discusses extensively in She-Wolves:

Laura: I kept being like, “I want to see these women, I want to get a visual.”

Paulina: You will not find photos. You won't find photos. I do have a lot of images in the book, but in the early years, it was easier to find images. When I introduce the 1980s, I have a still shoot of the set of the film 9 to 5 to show the outfits—that's how I was able to get a visual on it because we have so little. Trust me, I was searching. I was searching The New York Times and so forth, and LIFE Magazine, to find these images.

As I discovered with The Barbizon, these photos might have been taken, certainly, but the question becomes, what does somebody deem worthy of preservation? I think we're just back at that question.

Laura: What do you feel is the legacy of these women?

Paulina: As I say, I don't want She-Wolves to be read as some triumphalist account of Wall Street. It's shocking, horrifying. It's just like sometimes, you stop by the road to view an accident. At the same time, these women are incredible in the most complex way. It's not straightforward. They don't see themselves as feminists. They put up with things that maybe they shouldn't put up with, but they hang in there most of the time… actually, a lot of them leave. The ones who do hang in there, I hate to keep using the word perseverance, but somebody's got to be the first. Somebody has to. They were, and now at least there's a story about them.

I think in terms of legacy, I wish I could say that they had the chance, the opportunity to change the playbook, but even as we see so many women on Wall Street now, and it's a totally different atmosphere, a lot of that still looks the same, women have those same experiences. When you look at the very top, the percentage of women is extremely low still. In no way do I blame these women. They came in the 1950s. The last thing they could do was think about how to rewrite the playbook that was in place. They had to figure out how to fit into it, how to contort themselves around it. Just something as simple as bathrooms. I talk about ladies' bathrooms all the time in the book because Wall Street was literally built for men. When women came, they didn't have bathrooms in all these institutions, the New York Stock Exchange, The Wall Street Journal offices and so forth.

Their legacy is enormous, but I hope at some point, the legacy will be that women do manage to rewrite that playbook, though it's not looking that positive these days. What's troubling is that the story I tell is basically the story that's being consciously repeated in Silicon Valley. Women have already sued and protested, who work there, this culture of power-hungry, sneaker-wearing Silicon Valley bros. The misogyny is there. Now it's going to be in our politics too. That is disturbing to me, the fact that that same pattern, but a throwback to the worst of it, is being replicated. In a new industry, the idea that a very old, tired playbook is being used is really exhausting, frankly.

Laura: Earlier in our conversation, you mentioned that #MeToo hadn't come to Wall Street. How much, and you just said that it has changed some, but how much has it really changed in terms of sexism and sexual harassment?

Paulina: The reason I think that #MeToo didn't come to Wall Street is what I was saying about secrecy and everybody's legacy. Also, everybody's pocketbook is tied into that, so you can't name names because then nobody will trade with you either. This was a big part of the problem that women would say, "I can handle the harassment. I can handle the pay inequality. I can't handle the fact that men will literally not do trades with me, that I'm being left out of the game. That's the inexcusable part of this all."

In terms of how much has changed, I would say that the kinds of egregious acts that I write about and experiences are very uncommon today, but then I was giving a talk in Brooklyn and somebody in the audience, her daughter graduated a couple of years ago and she's in the music industry, but her two best friends went to Wall Street. One of them has already left because of the sexual harassment she experienced. I was shocked to hear this. In fact, everybody in the audience gasped when she revealed this. I don't know the details. We haven't had a chance to talk, but it did shock me. It told me, okay, it might be the exception that proves the rule, that it's all better, but there's still some, as they like to say, bad apples. I'm sure that's true to a point, but it is still something about that playbook running just as it did before with some gender adjustments.

Laura: Yes, and I'm sure with the fact that you sign an arbitration agreement, I'm sure there's an NDA and all of that along with it.

Paulina: Exactly. A lot of people argue that as long as that exists, as long as these cases can't be brought to court, you can never lift the veil. It’s depressing, but the women's stories also show tremendous, I think, creativity. Genuine skillset built upon this, creativity based around this. I think that's a great asset. I think, hopefully, that is being recognized more as an asset.

Laura: The stories of these women that you tell, they were obviously so good at what they could do at the various jobs, so they were able to leapfrog and break through all these barriers that the men around them constructed.

Paulina: There are so many amazing stories here, crazy stories. I guess I'll very quickly end with a story, simply because I've pointed to her a couple of times, and people might be wondering who she is: Muriel “Mickie” Siebert. She was the first woman to buy a seat on the New York Stock Exchange. She was an icon on Wall Street. She followed a route that a lot of women coming in the '60s and '70s followed, starting in low-level entry positions, figuring things out. She did that, but she did it 10 years earlier.

She arrived in 1954 in a beat-up Studebaker with $100 in her pocket. She had quit college. She got a job on Wall Street, once she discovered she has to lie and say she did finish college, and she was put in the research analysis department, where each person was in charge of a certain industry, and they would have to do all the research into the industry, the companies, and then they would recommend to their firms, to the clients, certain stocks. She was the teletypist gal, so she would run from the teletype machine with questions for the analysts, run to their desks, get the answers, send them back.

She—like the women who started to climb that ladder later—watched and listened. She realized that when she saw a page full of numbers, as she said, “it lit up like a Broadway marquee.” She became an aviation expert research analyst, very respected. She was at these small brokerage firms because the big ones, J.P. Morgan, Lehman Brothers and so forth, they were not hiring any women outside of secretarial pools. She, like other women, was jumping from one to another to get promotions, to get salary raises. No matter what, she was always massively out-salaried by young men coming in. She finally had enough. That's why she ended up buying a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, which was a crazy thing.

As she's doing this in 1967, there's another phenomenon taking place on Wall Street, which is the sweater girl. In May of 1967, this young woman from Brooklyn, naive to the world, has gotten a job as a data entry clerk on Wall Street. On her first day, she arrives from Brooklyn, coming out of the subway on Wall Street at 1:28 PM, and she has a very large chest, a 43-inch chest. Somebody notices her, tells his friends, who tell their friends. People start to gather at 1:28 to see her emerge from the subway. By September of that year, as Mickie Siebert is working on getting a seat, there are thousands—and I have a photo of this in my book—there are thousands of people on Wall Street waiting for the sweater girl, for Francine Gottfried, to appear. She, of course, by now has a police escort as well.

Take these two things, these two contradictory things that are happening in 1967, and I think Wall Street itself continues to be rife with contradictions.

Laura: It's really interesting to have those two stories paralleled.

Paulina: Yes, and they're happening at the same time and, as I say, they're really emblematic of the paradoxes that take place on Wall Street throughout.

Okay, that was fascinating; thank you!