The Push Pin Legacy

If you are in NYC in the next few weeks and interested in graphic design, then I highly recommend you visit an exhibition currently on view about Push Pin Studios. On until February 6 at Poster House, the first museum in the United States dedicated exclusively to posters, is ‘The Push Pin Legacy’—a lushly illustrative exploration of Push Pin Studios, its many members, and their role in instigating a resurgence in commercial illustration and graphic design.

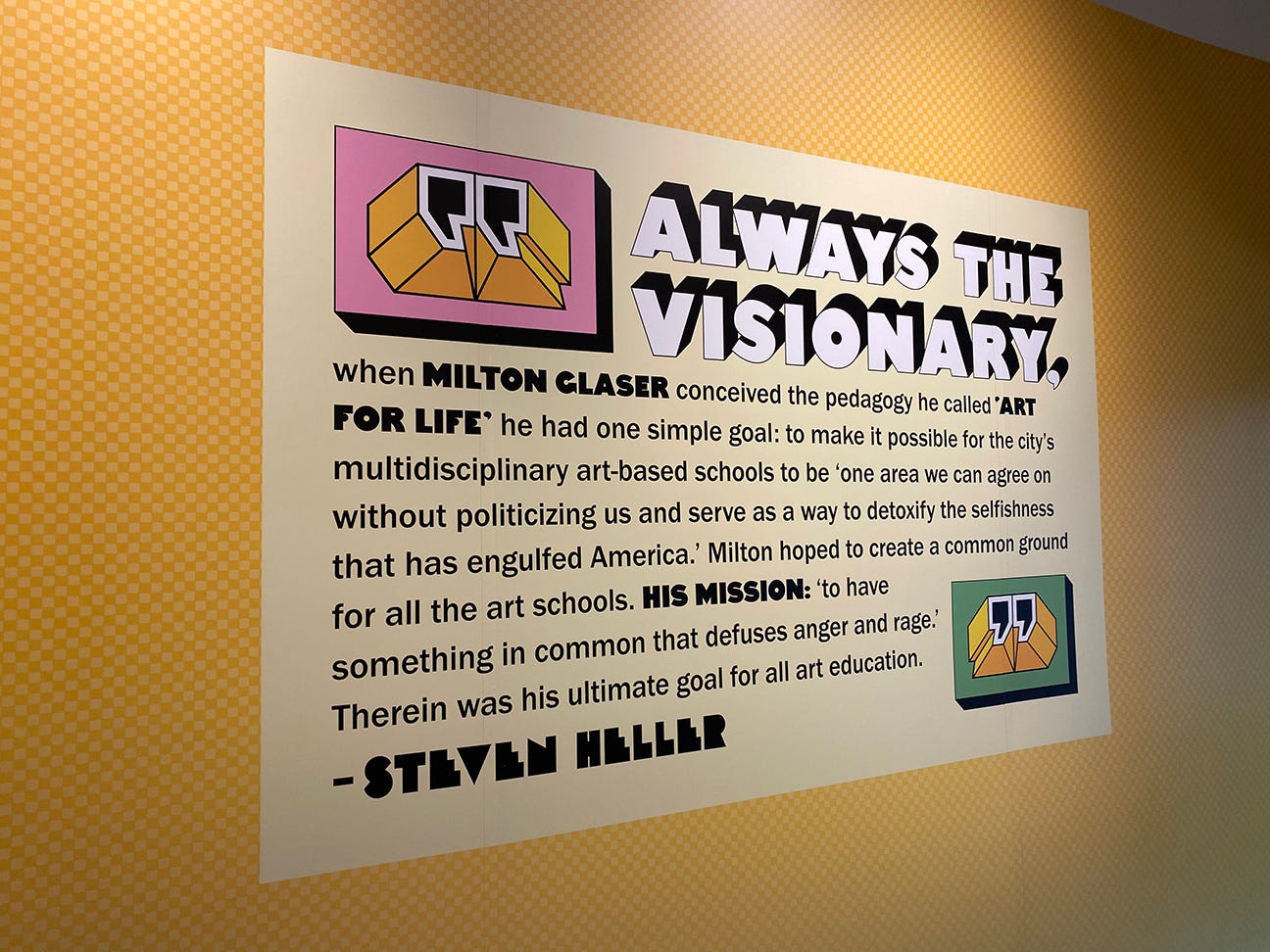

I was going to suggest that you visit it in tandem with a small show about Push Pin co-founder Milton Glaser at the School of Visual Arts (where Glaser taught from 1960 to 2017) but unfortunately SVA’s buildings are now closed to visitors due to Covid concerns—please check back at this page to see for changes. Hopefully the buildings will reopen to visitors before the show closing date of February 5. Petite and lovely, at the entrance it features a mini-street scene with recreations of shop windows showing off Milton’s designs for book covers, album covers and wine bottles. The other room includes a wall of posters he designed for SVA as well as his office, placed piece by piece exactly as he left it—a moving tribute, and an inspiring one for all fellow messy artists to see.

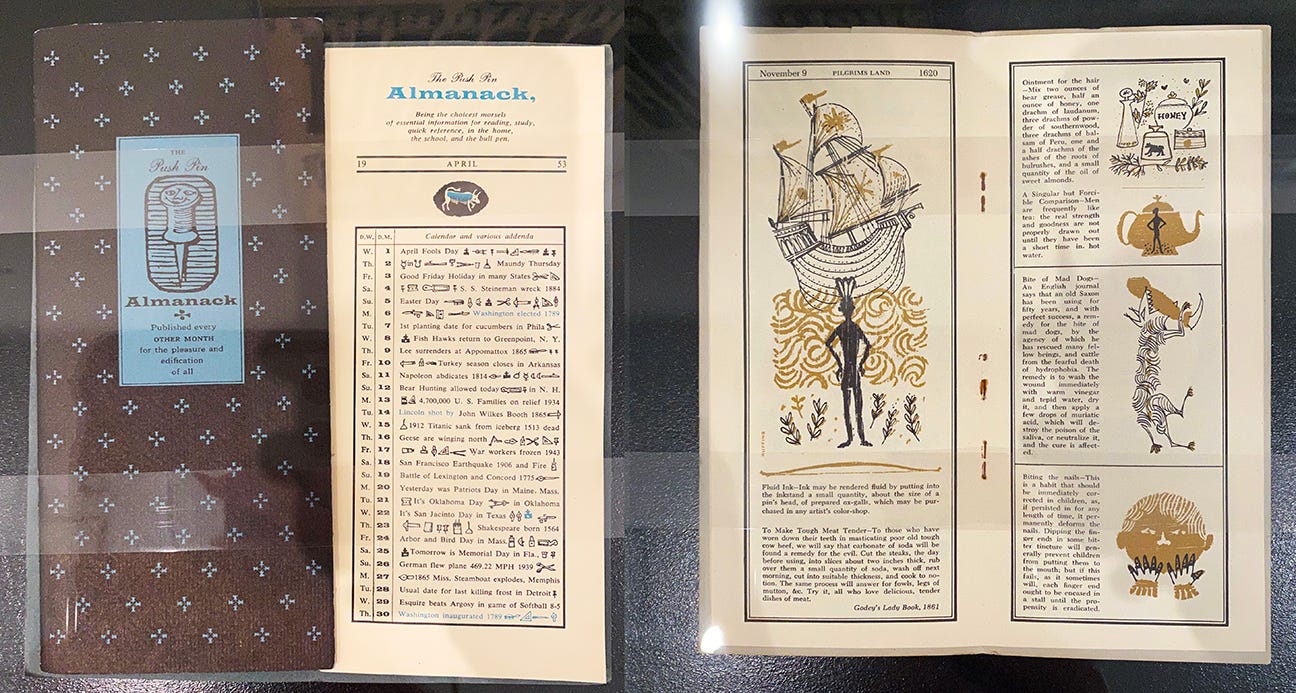

It’s hard to qualify just how influential Glaser and the studio he co-founded were on packaging design, graphics, typography and advertising over the last 60 years. Their influence spread far beyond New York and America, directly impacting the way books, records and goods look and are sold all over the world. Seymour Chwast and Edward Sorel graduated from Cooper Union in 1949 and soon found themselves searching for freelance work. In 1951 they came up with the idea of producing a monthly mailer to promote their skills, riffing on the traditional Farmer’s Almanack to create the Push Pin Almanack. Reynold Ruffins and Milton Glaser joined the duo, and they “used the Almanack to show off their collective, retro styles that blended graphics with typography and bucked the dominant representative, illustrational designs produced by Madison Avenue.” A slim volume, it was filled with miscellany, calendars, horoscopes, anecdotes, printing-related ads, excerpts from 1860s ladies advice columns, and historically inspired illustrations.

Distinctive and individual, the Push Pin Almanack quickly grew an enamored following that led clients to their door. With the name now widely known, in 1954 they established Push Pin Studios. Over time the project evolved—becoming the broadside Monthly Graphic in 1957, and then the erratically published Push Pin Graphic from 1961 to 1980. All forms of the publications were and continue to be incredibly influential—not only gaining new jobs for the ensemble studio and the artists it came to represent, but also directly inspiring the work of artist subscribers and present-day collectors. The exhibition begins with many examples of the Almanack and Graphic, alongside studio ephemera like badges, stationary and exhibition posters.

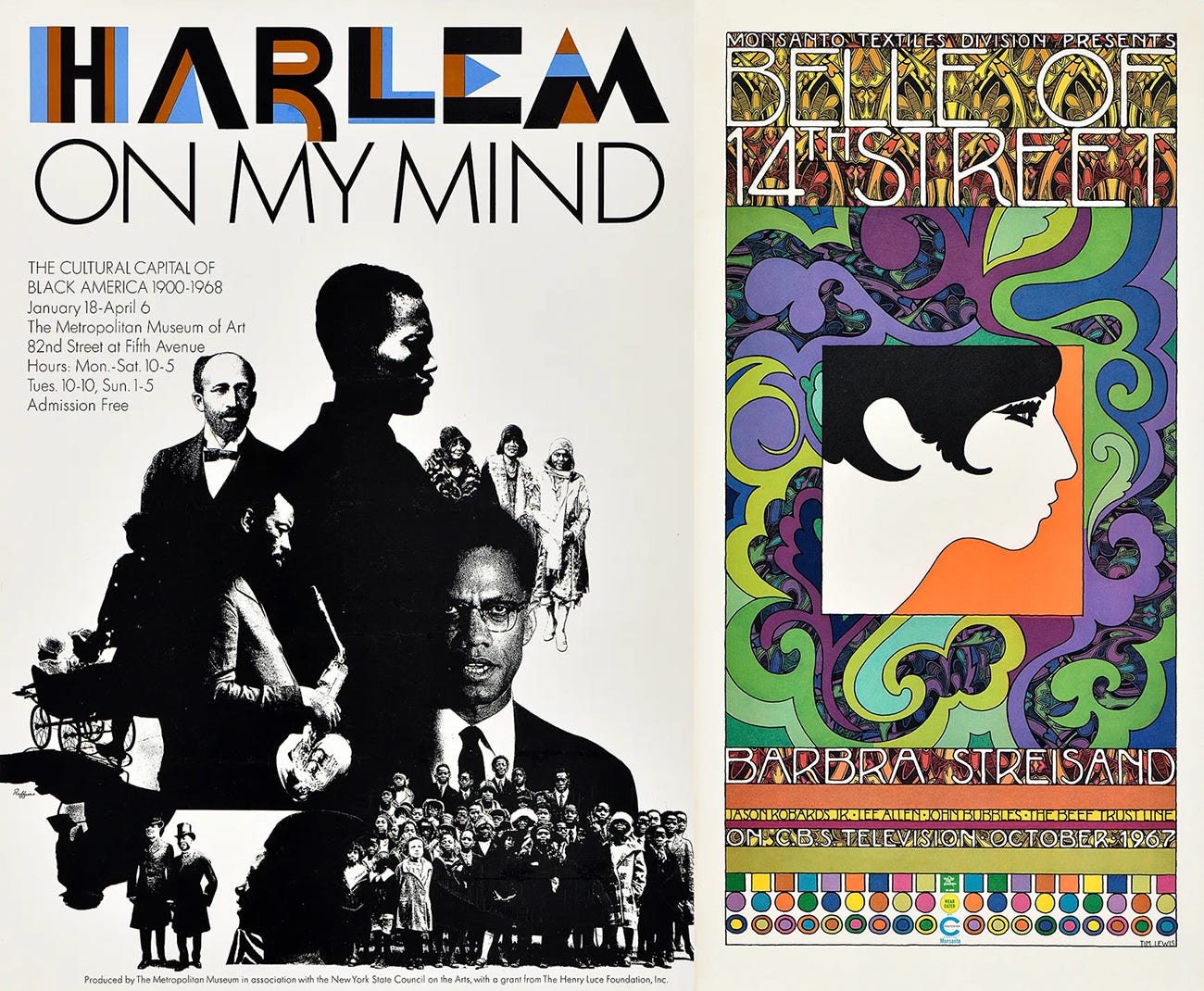

A wall of music posters brings the Push Pin vision into graphic, rainbow focus. A glorification of joy, these posters reflect the studio’s rejection of “the rigidity of modern minimalism, representational illustration, and sans-serif typefaces in favor of brightly colored, abstracted illustration that combined images and often flamboyant or novelty lettering that looked back to the late 19th- and early 20th-century poster styles if Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Lucian Berhard, and Ludwig Hohlwein.” Iconic images that are seared into our collective soul, posters for such greats as Barbra Streisand, Dionne Warwick, Mahalia Jackson and Bob Dylan showcase the creativity and color that characterizes Push Pin’s work. Smaller in scale but no less rich in texture, their album cover designs extended the reach of the studio’s influence—now in the hands of most consumers, from classical music aficionados to jazz lovers and more beyond.

As time went on Push Pin expanded beyond the original foursome, with the new illustrators and designers who joined all truly bringing something new and different to the collective. The outro to the show lists 92 known members of Push Pin across the years; this exhibition highlights only four beyond the co-founders: John Alcorn, Barry Zaid, James McMullan and Paul Davis. John Alcorn joined Push Pin straight out of Cooper Union in 1956—according to a didactic, Milton Glaser described him as “the baby-faced design prodigy with golden hands.” Known for his ability to replicate, jump across and meld styles and genres, Alcorn’s work with Push Pin can truly be seen as the zenith of commercial psychedelia. Highly regarded throughout his short life (Alcorn passed away at 56 in 1992), he moved to Italy in 1971 where he worked with Fellini—during his time in both Florence and back in the United States, he produced wonderful covers for hundreds of books.

In terms of fashion, there are only two Art Deco-inspired posters by Barry Zaid for the French designer Daniel Hechter—but the through line between Push Pin’s work and fashion and, in particular, textile design is very clear to anyone knowledgeable. The Canadian Zaid is a self-taught artist—he joined Push Pin in 1969 after working in Toronto and London. Much of his work features similar flattened, Art Deco-style ladies in motion. After leaving Push Pin in 1975, he established a highly successful practice of his own—if you’ve ever picked up a box of Celestial Seasoning tea, then you’ve likely become acquainted with his work. I know we aren’t choosing favorites here, but he’s mine.

With a bookcase filled with gloriously covered books and walls layered in wild, bright posters—all designed by Push Pin artists—I could gladly have moved in to this exhibition. If nothing else, their designs should make you happy—but they will likely make you think about good design and the wonderful role it plays in our life and in our history.

The Push Pin Legacy: September 2, 2021–February 6, 2022

Poster House, 119 W 23rd St, New York, NY 10011

Ah! Your pic of the Seymour Chwast biker poster inspired a dig into his archive…I have a copy of his Canterbury Tales, all on motorcycles! Methinks he liked two wheels…