Somehow I missed that the great Pablo Manzoni passed away on February 2. One of the first makeup artists to become a star in his own right, here is an elegy and love letter to a true arbiter of glamour and elegance.

The Chicago Tribune described him as “the Merlin of makeup,” due to the skill with which he could refashion a woman’s face through cosmetics. There were few others with the fame, talent and natural elegance of Count Paolo Michaelangelo Zappi-Manzoni di Giovecca. Born in the countryside near Bologna in 1939 to Count Zappi-Manzoni, a surgeon, and his wife Ersilia Monti, Pablo was always “interested in colors, in art.” He became interested in makeup by watching movies.

“Makeup should be a lovely way of lying about yourself. It should whisper, not shout.”

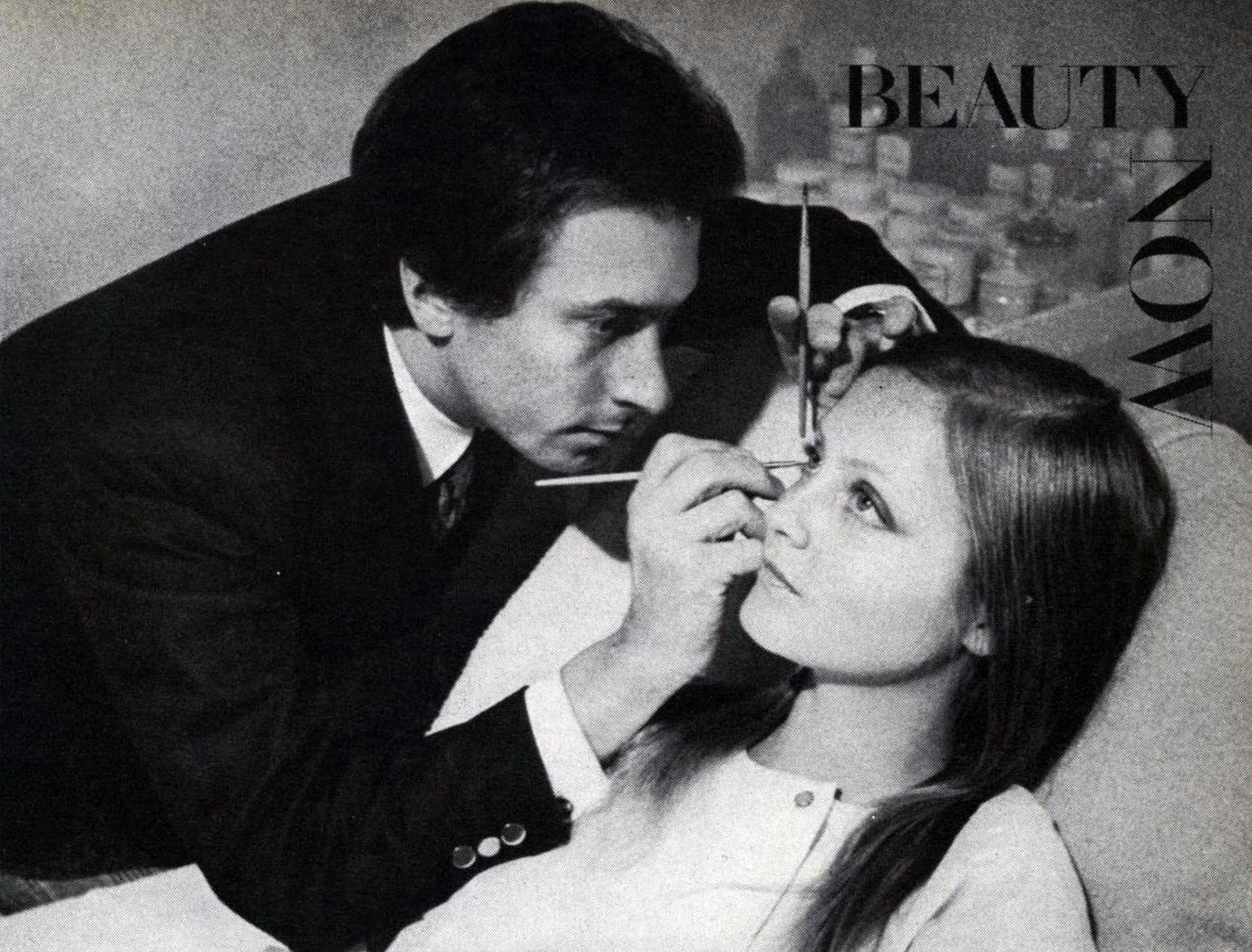

At 17 he persuaded Princess Sciarra, the manageress of the Elizabeth Arden Salon in Rome, to hire him—though he had no experience, his father’s title and his clean-shaven, well-manicured look helped gain him entrance. According to an interview in Harper’s Bazaar in 1984, he lied and told them that he was a professional makeup artist from Cinecittà who disliked the early hours. He relayed how, on his first day, he was sent to make up a woman in room No. 5: “I walked down the long corridor, shaking and perspiring. The only victims I had ever made up were my school chums. I entered the room and looked at my client from the back…She sensed that I was nervous and said, ‘You are new here…where have you worked?’ I answered, ‘I do makeup for Myrian Bru, the French actress.’ With that she turned around and said, ‘I am Myrian Bru.’ And I said, ‘Yes, and I am doing your makeup now.’” He chose the Spanish version of “Paolo” for his professional name, and for many years was simply known as Pablo.

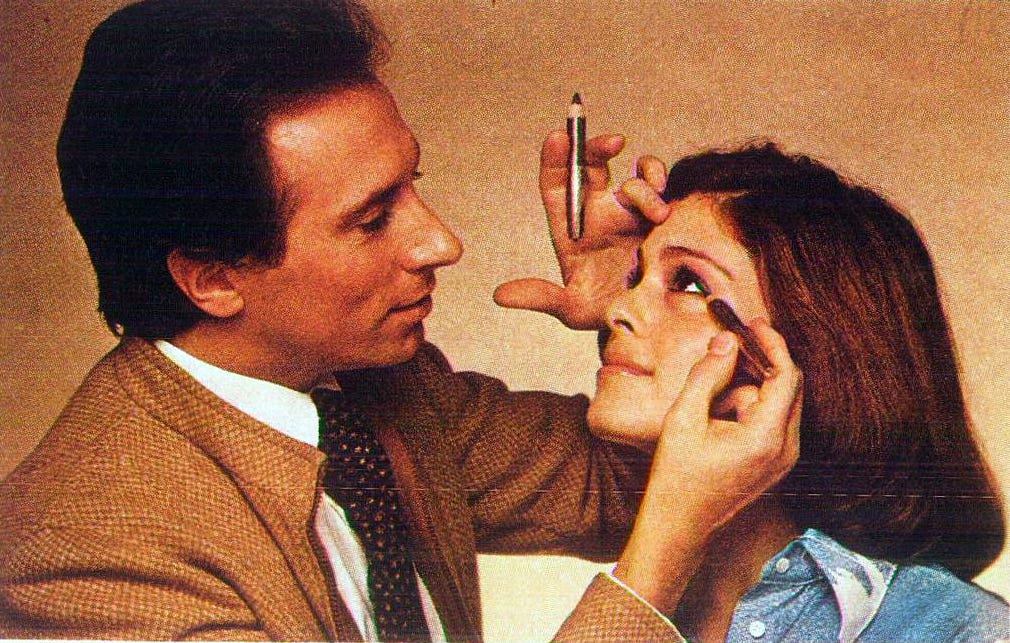

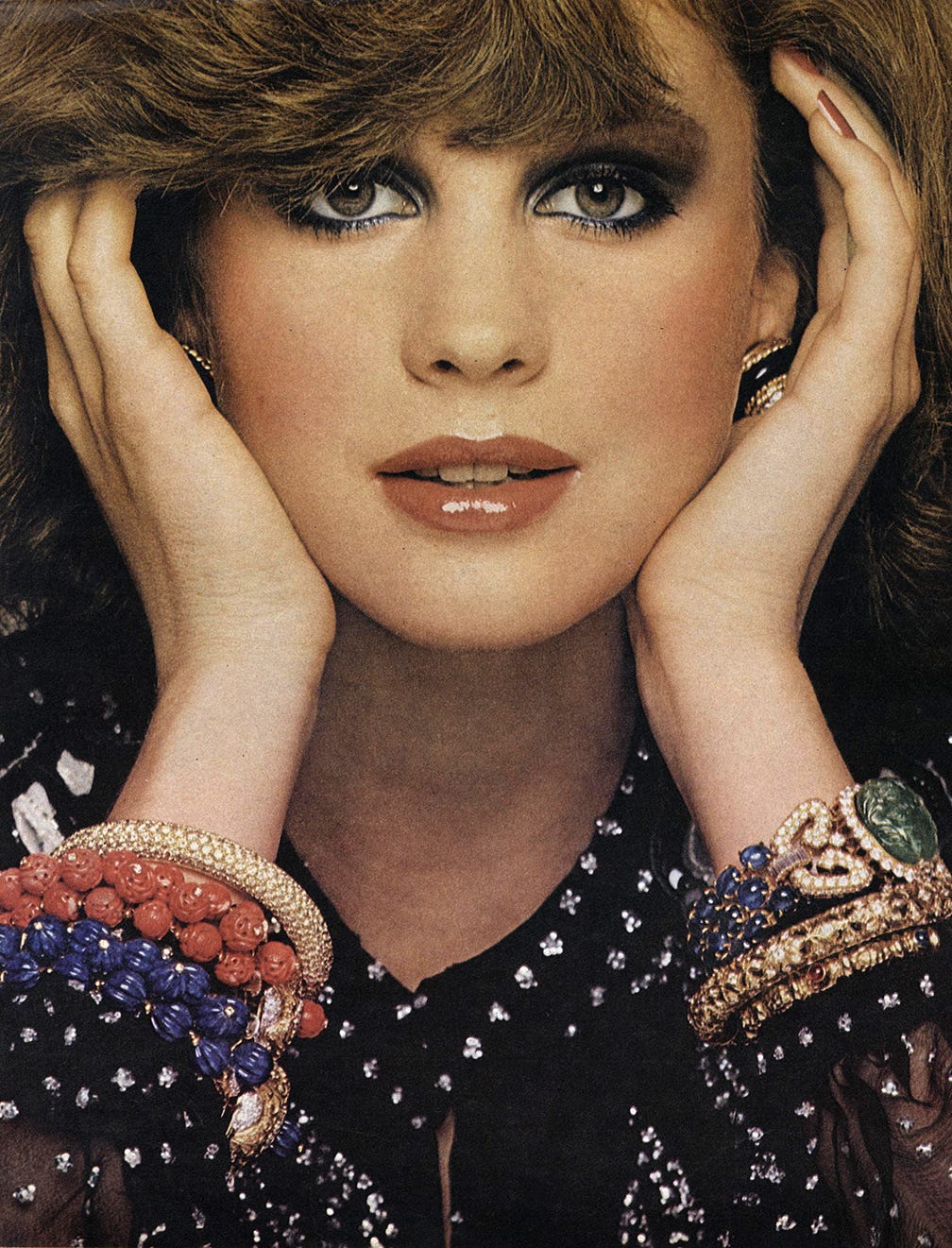

Beyond his talent, much of Pablo’s drawing power came from his place in Italian society as the son of a count. He used this—plus his immaculate manners—to bring in high society clients who he then made over into fantastical, glamorous beings. In 1961 he became beauty director of the Elizabeth Arden Italian Salons. Among his most well-known innovations was lightening eyebrows (bleaching them lighter than the head, then using a liner to darken)—as he did to Sophia Loren—as “it frees the eyes. Make-up and the décolletage are the only weapons of all-out femininity women have today.” Believing that eyes are the most important feature, he also became known for using double layers of false eyelashes. Three years later Elizabeth Arden (real name, Florence Nightingale Graham) chose for him to come to America to be the face designer, or visagiste, for her company.

“Practically every woman has nice eyes that can be made more beautiful with make-up—but every face has something interesting to work on and never mind the flaws. The world’s most celebrated beauties all have imperfections…”

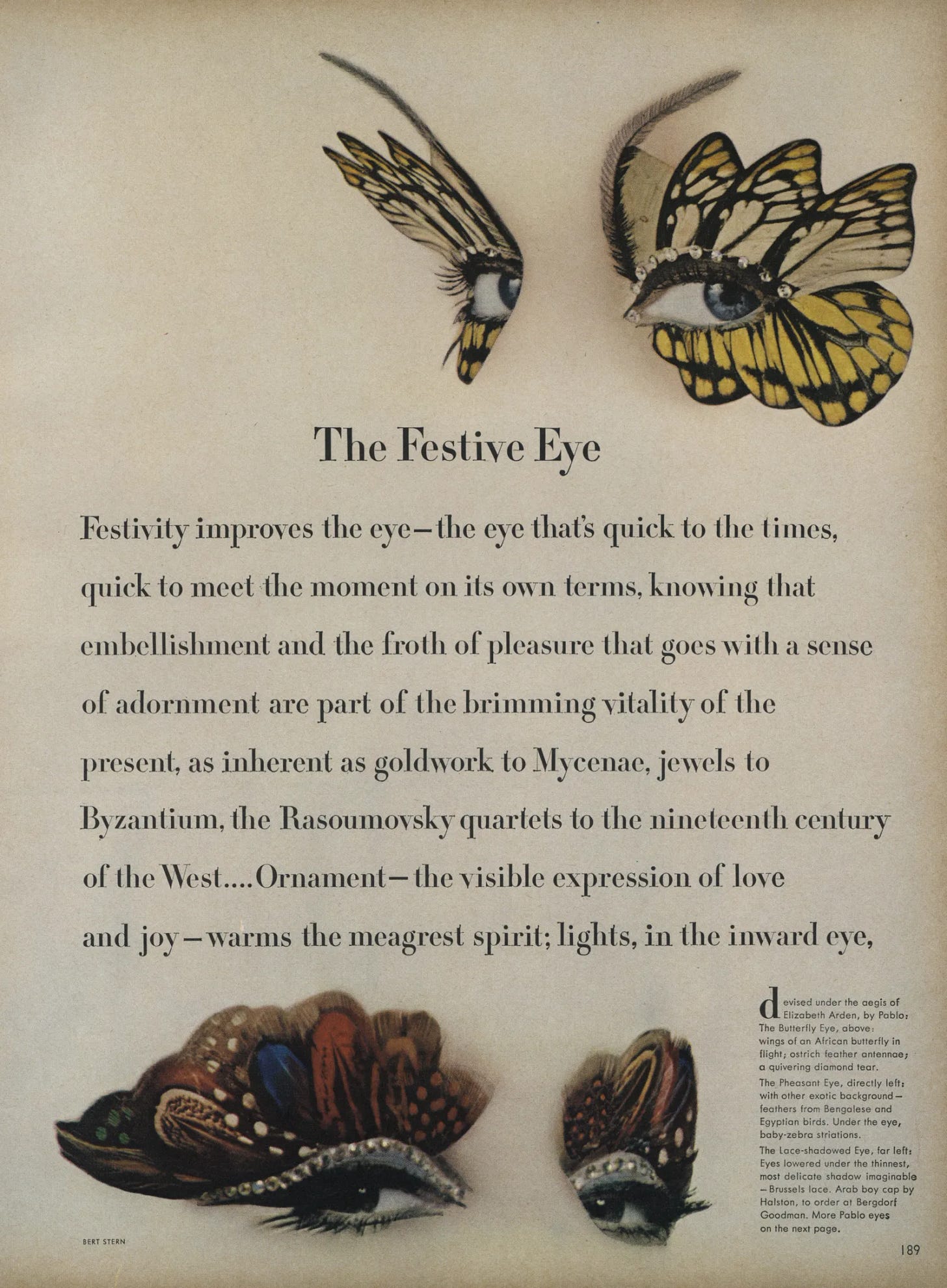

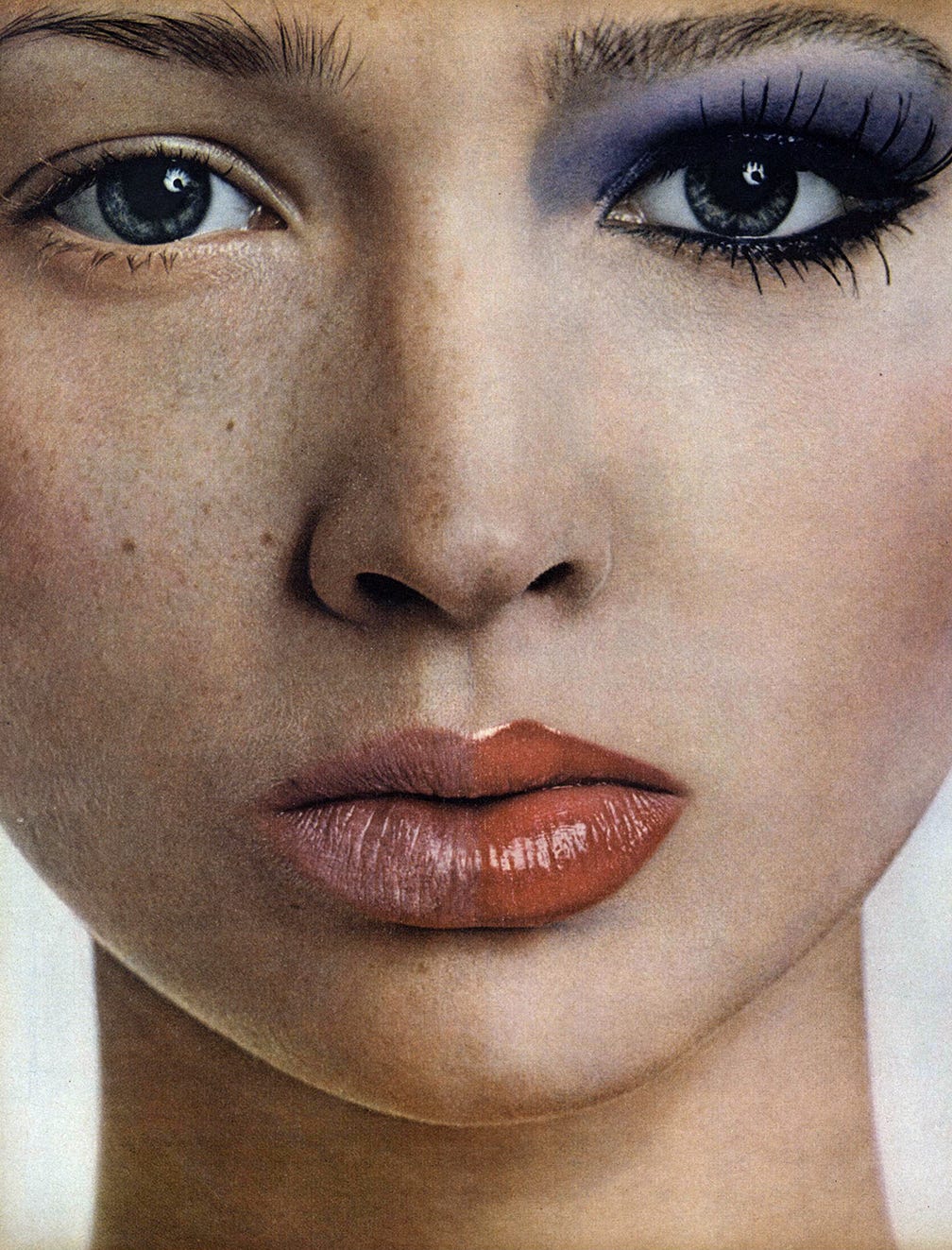

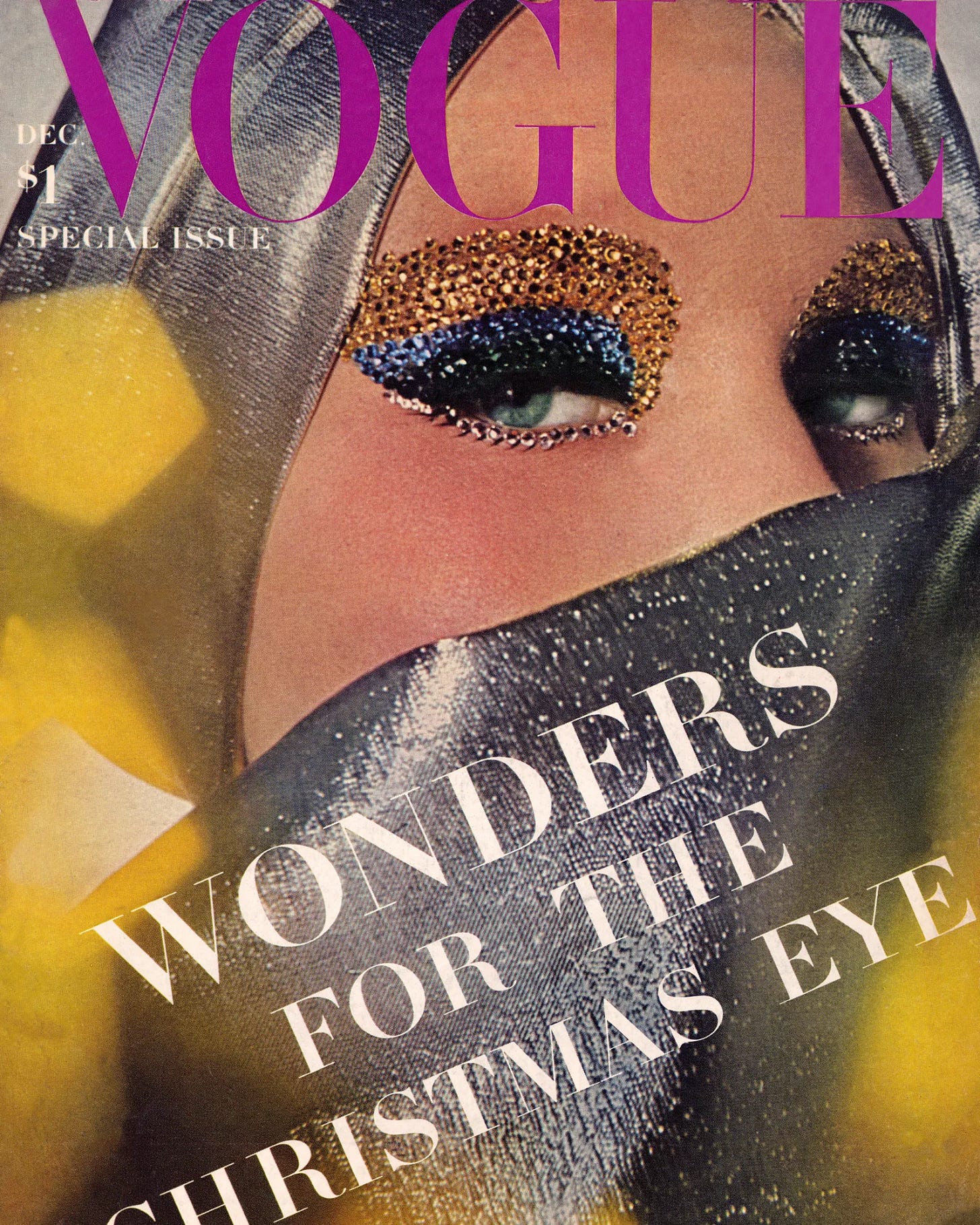

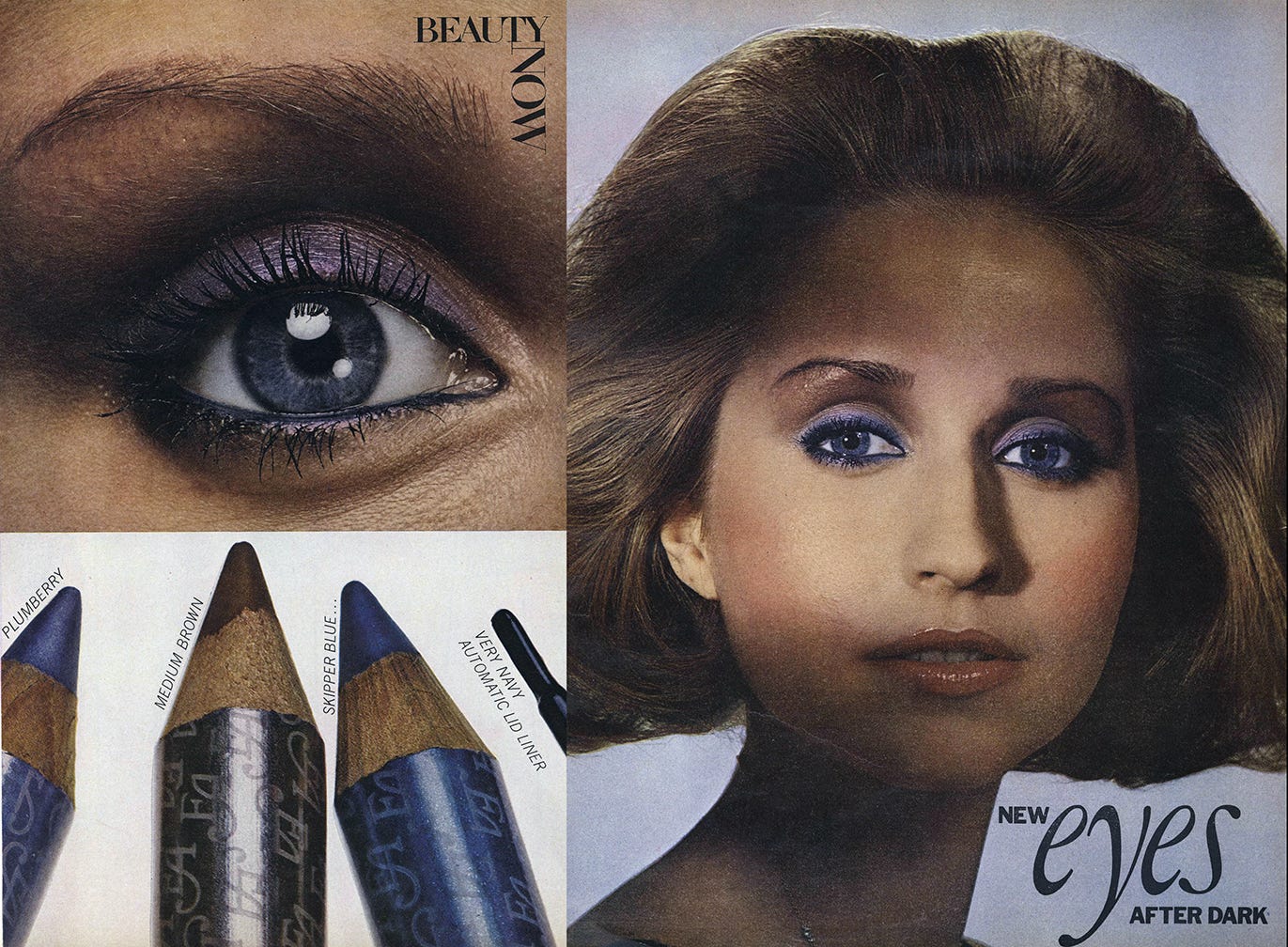

Pablo stepped into his larger role on the American scene at exactly the right time. The pendulum was swinging away from the artifice of 1950s beauty to an interesting combination of “the natural look” and fantasy. In 1965, the New York Times documented how, “In the last two years, since naturalness has become the theme of the beauty industry, it has added hundreds of products and sent bewildered women scurrying into one of the biggest back-to-school movements of modern times.” Those schools? Private salon sessions and department store classes led by makeup artists, who were emerging from behind-the-scenes for really the first time (other than Max Factor). Contrasting with the “bejeweled, befeathered and lace-trimmed eyes” he created for Vogue, his $20 half-hour sessions in the Arden salon focused on enhancing a woman’s natural beauty (by 1966, the price was up to $32.50). Soon headlines crowed such legends as “Make-Up Man Emerges As Star on Beauty Scene.” That year he received a Coty Awards for innovations in face design—the first make-up artist to win one.

Elizabeth Arden passed away in October 1966. The following year, Pablo was elevated to the role of creative director—now responsible for developing new products and colors for the Arden laboratory.

“Too much is vulgar! If a woman’s cosmetics are as obvious as a mask, so is she!”

Manzoni had three distinct modes of make-up: the fantasy (exemplified by zebra-patterned eyelids), which defined his career and which he saw as solely for fashion editorials; the glamorous, dramatic looks he gave to celebrities; and the more natural look for regular women, which sought to enhance rather than remake their features. For all the notoriety his sequin-covered lids had brought him, Manzoni’s personal philosophy was much more natural. He was not a fan of contouring or dramatic makeup for regular life; nor was he a fan of trends. Make-up was instead about working with an individual’s look. Though he was in charge of creating novel products and looks, Pablo was strongly against women changing their beauty looks often and hated the thought of make-up artists pushing too many items on a customer: “The artist may have made a big sale but it is a lot harder to make a happy customer. When the woman gets home, finds out she doesn’t have the time or ability to apply all these products, she is unhappy. We try to make happy customers by showing them a few basic products that will improve their appearance but not so many they get confused.”

“I am a great believer in luxury. To me, true luxe is the best of good taste… I think everybody deserves as much luxury as he or she can afford: the longer we live, the more we are entitled to! Be good to yourself to the greatest degree you can afford to be—there lies happiness!”

Until I started researching this, I hadn’t known of Manzoni’s close work with the plastic surgery industry. In 1970 he was invited to speak about the importance of makeup and grooming after surgery at a symposium on aesthetic surgery. As stated before, he truly believed that “elegance is imperfection” and that people should come to accept their individuality. While Pablo was “against surgery which changes features,” he understood the benefit of surgeries for youthfulness. Due to his experiences at the symposium and with clients, Manzoni came to realize how new makeup looks were necessary following surgery—not only had women often fallen into certain habits to compensate for a large nose or heavy eyebags, but generally, a new face required a new approach. He introduced in-depth post-surgery sessions at a special salon behind Elizabeth Arden’s famous red door in New York—with a doctor’s recommendation, women could come in for two two-hour sessions to learn to style their new visage. Women started coming before surgery to get his advice, and he frequently discovered that the surgery wasn’t necessary at all. “I had an advantage—my own attitude, for in Italy it is automatically considered the most beautiful women are over forty,” he told Vogue in 1973. “I came to the decision unless a defect in a woman’s face was causing a mental imbalance, I would advise against surgery, and show her how to use makeup to succeed.” These sessions changed from pre-surgery to instead teaching “how to face up to life, rebuilding lost egos…”

“In this country women are obsessed with perfection, which is very silly. You like to achieve a perfection in features, in looks, in things which are unnecessary. I think that the only chance a woman has to look individualistic is to be different from others. And in order to be different, you must welcome your little flaws, turn them into assets, and capitalize on them. The most beautiful woman in the world have marvelous imperfections. Imperfection is personality, character, individualism, and that is much more important than being a copy of someone else.”

With his role as creative director taking him out of the salon and instead to stores across the country, his philosophy about beauty became more defined. All of the women he met simply made him believe even more in makeup that emphasized without distracting: “A face needs to be believed. If a woman makes herself up to look like what she isn’t she’s ridiculous.” In 1972 Arden introduced a new concept and product line based on this philosophy: Self-Expression. He believed a face should be touchable, believable. Though he always spoke of the eyes being the most important feature, he also placed a large emphasis on blush. His obsession with eye actualized as a dislike of eyebrows—every interview speaks of bleaching or plucking them (though not too thin). He found Ali MacGraw and Margaux Hemingway intriguing due to the individuality of their brows but was very clear in his belief that women shouldn’t follow their lead.

“Why be undressed? Why be decorated? A woman needs makeup—a brunette usually more than a blonde—to take advantage of her good points. That’s what makeup is about.”

Instant Beauty, Manzoni’s book on how to make-up their face in a time-efficient manner, came out in 1978. Among the procedures described were a “10-minute miracle” and a “20-minute masterpiece,” while he also included a five-minute look that emphasized all but the eyebrows (“Let’s forget about them”). As he told one newspaper, “Rather than a contrived approach, I want to show a woman how to cope, how to bear having a flaw…psychologically, to help her be optimistic when she looks into a mirror and not have so many complexes. I want her to turn a flaw into an asset and accept imperfections as individualism.” When compared to other beauty authorities of the era, Manzoni’s philosophy of embracing one's flaws and reveling in individuality appears strikingly modern—his ethos has more in common with much of our current body positivity movement than what other makeup artists were advising at the time.

“I’m terribly casual, and I think a woman should approach the whole idea of makeup with pleasure, instead of looking at it as a routine that must be maintained.”

After twenty-three years with Elizabeth Arden, Manzoni left at the end of 1979 to establish his own consultancy. From a salon in his apartment at 465 Park Avenue, he began consulting with private clients. By 1989 he was charging $400 for a 90-minute consultation—there he could recommend products from all brands (no longer tied to just Arden) to the world’s most glamorous and rich: Jackie O., Nancy Reagan, Gloria Vanderbilt, Bianca Jagger, Sophia Loren.

“When you are Pablo of Elizabeth Arden for 23 years, your blood is turning pink, literally, and you have no last name. What is Pablo, a fettuccine dish?”

In 1990 he became creative director of La Prairie’s Affinite Naturelle cosmetics. Signed to a four-year contract, the collaboration went sour after he was only paid one of his promised bonuses. In 1996 he sued La Prairie. He had kept his salon open in the Ritz Tower throughout this time, and continued to consult until around 2000—it is unclear when he officially retired. In 2015 Doyle’s held an auction that included many Old World antiques from his collection. On February 2, 2022, Pablo passed away due to complications from back surgery at age 82.

“We are too much coordinated. It’s feeding people’s imbecility to tell them to match their makeup to their clothes."

Perhaps what is so interesting about Manzoni is his fame—in our current world where makeup artists are huge stars with giant cosmetic brands, it is important to remember who led the way, who made it possible for the Pat McGrath’s of today. As we recenter him in the pantheon of beauty savants, it is important to look at the entirety of his legacy. By remembering him solely for his extravagant fashion work, we are discarding most of his career and beauty beliefs. As I hope this essay has made clear, Manzoni truly believed that beauty could be found in every face, in every woman—a powerful and necessary vision of beauty, for then and today.