Edith Farnsworth, Glass, and Rewriting Women's Narratives with Nora Wendl

Reappraising Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Modernism through Women's Stories

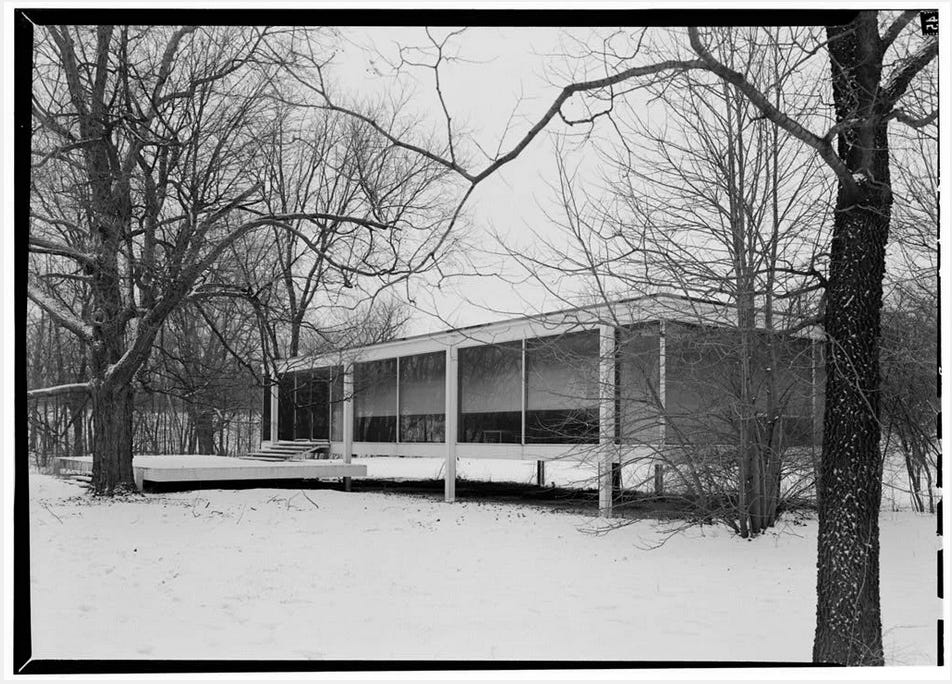

There are certain buildings that have an effect far beyond the world of architecture—they capture the public’s attention, drawing them in not just by design but also sometimes through legend, some drama related to its conception or construction. The Edith Farnsworth House, in Plano, Illinois, is one such edifice. Since it first appeared in the press in the early 1950s, it has been the center of court cases, rumors, attacks about its character (can a building be “undemocratic”?), intrigues, and more, lending it a power far beyond its glass walls.

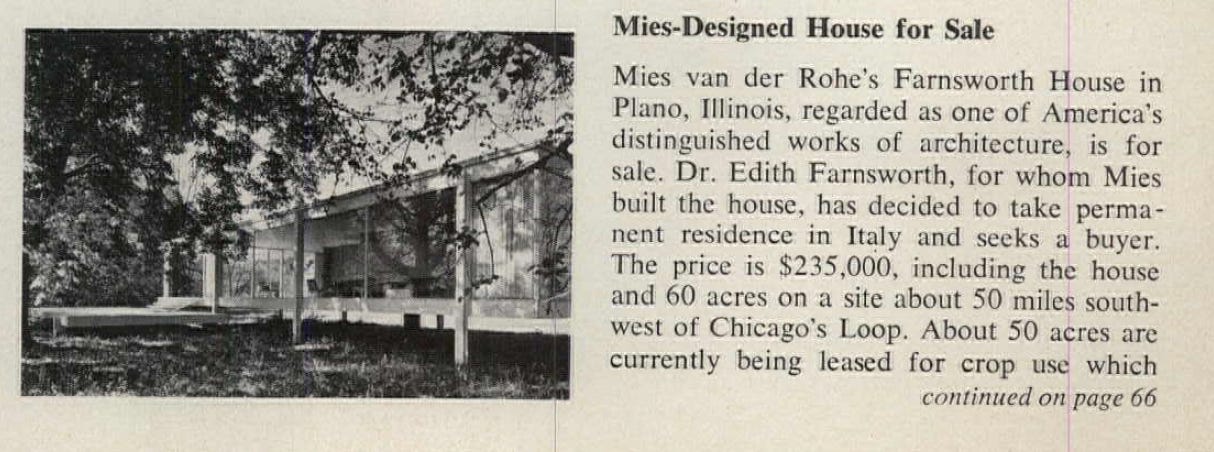

For seventy years, it has been commonly repeated that the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe had an affair with Edith Farnsworth, a noted nephrologist, during the construction of a weekend home she commissioned, on a rather desolate site in a field overlooking the Fox River. When the build went far over budget and as floodwaters came perilously close to invading the raised house, the affair soured. He sued her for ownership, she countersued and won, yet all that is remembered is the scandal of the supposed affair with Farnsworth painted as the bitter, jilted lover who hated the house.

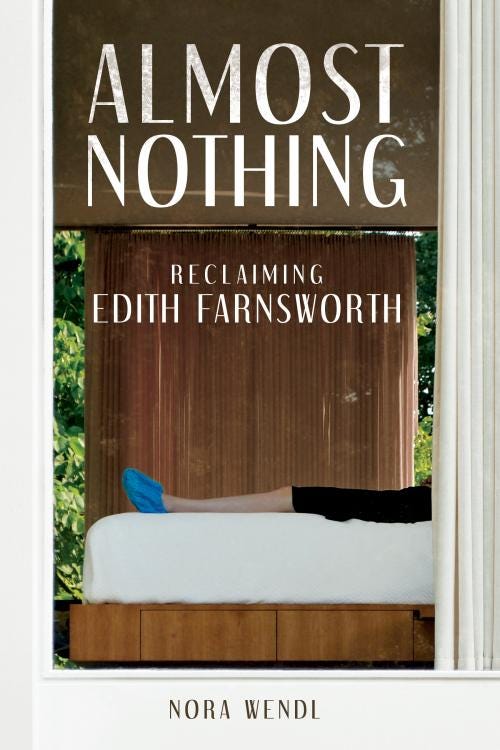

Over ten years ago, Nora Wendl (now a professor of architecture at the University of New Mexico) set out to unearth the truth behind the rumors. Was there even an affair? What did Mies and Edith actually think of each other? And what did she really think of the house, a house so modern that it was seen as an affront to American values? Looking through Edith’s writing—an unpublished memoir and reams of poetry—Wendl slowly reconstructed a totally different understanding of Edith Farnsworth and her famed House. Her new book, Almost Nothing: Reclaiming Edith Farnsworth, seeks to do just that while also exposing the patriarchy’s grip on this continuing narrative. A sort of duel memoir-biography, Wendl interweaves her experience of researching this book over a decade with her discoveries about Farnsworth. It’s fragmented and poetic, with both women’s travails in male-dominated worlds taking equal importance.

Last month, I spoke with Nora about her book. It was one of those conversations that touched on everything, swirling around architecture, education, poetry, writing, misogyny, photography, glass, and always coming back to being a woman. If you’ve ever wondered what it is like to live in an artwork—a glass box on view for all gawkers—or wondered what the emotional toil is of researching and writing a history, then this multi-layered book is for you in all its fascinating, painful, beautiful truth.

Almost Nothing is now available on Bookshop, Amazon, and wherever books are sold.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Laura McLaws Helms: What drew you to study, and want to teach, and want to study and teach about architecture?

Nora Wendl: I would say, I definitely was not a natural fit. I went to an all-girl Catholic high school, and the closest I got to art class was ceramics. I was eventually banned from the ceramic studio because everything I made exploded in the kiln, and it would take out everybody else's projects. I was lucky; I went to mostly public school in Omaha, Nebraska, and then had this four-year, pretty intense, Jesuit-adjacent education at a convent school that was really about getting young women interested in math and science. We had wonderful teachers. I think I had a lot of academic pursuits that I was really interested in.

Then, of course, you're 18, 17, and you're figuring out what you want to do for the rest of your life, which is insane. I looked at that list of all of the things you could do, you could be an accounting major, it could be a business major, engineering, architecture. I thought none of these things encapsulates all the things I really like. I loved creative writing, and I loved history, and I loved the art class that I was so dangerously bad at. I had a physics teacher who said to me, "You should probably study architecture.” I really enjoyed his class the most, because physics is an interdisciplinary discipline. I wasn't great at the equations parts of things, but I was very enthusiastic about it. It was really on the recommendation of that teacher that I went and looked at architecture programs.

The one I ended up going to, Iowa State, was, at the time, pretty heavily experimental. There were a number of women there who were theory professors. They were also teaching studio, and it was just the right fit. The ideas were really interesting to me. They were making experimental models. These were things that I'd never really done before, but I think because they were bringing together, weaving together all the things like the history, and the writing, and some science, and some material studies, and some art, but in these kinds of nontraditional forms. There were study abroad programs, and it just seemed like, "Oh, this is the world I was looking for."

The longer I've taught architecture, the more I've realized, I think architecture draws in people who are looking for a broader framework than a typical profession. I think it draws people who are really curious about making things, but maybe in a way that they haven't really been exposed to before. I think architecture is drawing people who don't find themselves aligned with any one profession, or one thing. I think the reason I got into teaching is because I just loved the education of it so much. I had such wonderful teachers. I was really lucky. I think public education is so critically important. The professors I had are still part of my life. They were wonderful people, and just lit a fire in all of us. I think because I had such a great experience, and loved my teachers so much, my dad jokes that I just never left school.

Laura: When did you become interested in Edith Farnsworth, and what spurred you to want to research her in greater depth than the cursory mentions of her that are repeated everywhere else?

Nora: I think one of my professors left on my desk this copy of the New York Times Magazine, and it was from 2003, and Peter Palumbo was about to put the Farnsworth House up for auction at Sotheby's. They did this little piece in The New York Times Magazine, and it had just the most disgusting title. It was like, "Sex and real estate”: “What's the story behind this house? It's so juicy. This house is a love child between Edith Farnsworth and Mies van der Rohe." I realized there was a juiciness to the story because they were trying to get people interested in wanting to buy this house, which Peter Palumbo was selling, because he needed to offload some property and make millions of dollars.

It seemed to me very suspicious that here this woman's identity was being used as this chip in this narrative that would sell the house. It felt really disrespectful to me. Then my professor put it on my desk, and he said, "I thought you would find something curious about this." He knew. I started looking into, “Okay, where are all the historical references of her? Where are they getting this narrative about a love affair?” Why is she being troped in this way that's really serving a narrative, rather than identifying something remarkable she did, which allowed the architect to build this remarkable house? I just kept finding over and over these really disparaging narratives, like Franz Schulze describing her as being equine in feature, focusing on her body, which I thought was so bizarre for an architectural historian to do. It didn't make any sense.

I thought, "Okay, if there's so much energy around slandering this woman, or saying really inappropriate things about her, there must be something great about her. She must be remarkable," because, of course, historically, we only tear down these women who are remarkable figures, right? I went to the Newberry Library, I think when I was in graduate school, and I started reading her memoirs, and I thought, "Wow, she was such a fascinating person." She was such a strong-willed, multi-talented, also a little bit opaque, and a little bit like performing her own character, sort of human. I found that so fascinating. I think it was really between undergraduate and graduate school that I started really fixating on her narrative, and who she was.

I thought, "Okay, I'm writing this weird book. I don't know what it is. It's part memoir. It's partly about this woman," but it existed in the back of my mind. I would keep returning to it and adding more to it. I think maybe the confidence to say, " I'm writing something that's both about me and my subject," I didn't really have that until after I got tenure, where it felt safe to experiment, and write the book in a way that I wanted to write it, rather than another historical approach to who this person was.

Laura: Did this book always have this form, that it was sort of a memoir/biography, dual memoir biography?

Nora: Not always. I did write a few academic essays first and I published those—they were essays, basically, about the construction of architectural history, the problems of the archive that's related to a woman's life… The museum archives too really didn't acknowledge her at all or acknowledge her only as a client. At the end of the day, I felt so outside of those, because, of course, when you're writing something academic, what's propping it up is the discourse, and that's not really your experience, your lived experience. I think that those were done, and those are really successful, and that really helped me get tenure.

I think it was after all of that happened that I was thinking, "Yes, but all these other things happened." In order to get this information, there are all these weird events that occurred that informed my ability to write about, or how I would write about, or what I would know about her life. I thought, "Well, that itself, if we're really thinking about historiography, and the making of history, and if we're really thinking about what it means to be a woman writing history, those things are really important to acknowledge."

One thing that really lit me on fire was reading again, Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own, where she describes being invited to give a lecture at this college, but she's not allowed to use the library. She's supposed to write a lecture about women in fiction, not women who write fiction, but women as a subject in fiction. She's like, "How am I supposed to write about this, if women aren't even allowed to use the library?" She writes about her experiences attempting to use this library to come up with this lecture that she's been invited to give, but isn't allowed to occupy the male spaces of the university, where she's giving the lecture. I thought, "God, it's so real." These things haven't really changed. They're such a part of the fabric of one's life. Of course, what you're allowed access to, and how you're treated, and how you're perceived, really change the way you can or cannot write history. I thought, "I really want to write those things into this." I just started to do it.

We hold up bell hooks, but we would never allow ourselves to write like bell hooks. I think I started to think about how critically important she is as an example, for instance, writing through the embodied experience of theory, not just writing theory, but the embodied experience of it. I thought, "This is the stuff I love reading, and it's the stuff that moves me. I'm going to write in that way, and I have to just trust that there's room in the world for that, and just workshop this in spaces that feel receptive to that kind of writing."

It was a slow process for sure. A slow process of allowing myself, a slow process of acknowledging what it was like to actually research this and admit to myself that I was encountering things that were difficult and crazy, and really different than the male experience of being a researcher and professor.

Laura: Yes. So much there. With the research experience, most of the time, there's this feeling that we're not supposed to show how difficult it is. Reading your book felt the closest—when you're talking about your own experience, your personal experience—the closest to the struggles that I've gone through.

I really liked how you brought in not just your own lived experience of writing it, but also trying to imagine Edith's lived experience of what it would have been to live in that house. Can you speak a little to that, and also to what you ended up discovering about her that was so different than what had been put forward in these mostly male historiographies?

Nora: It's funny, her memoirs don't talk much about her lived experience in the house. Her memoirs, it seems they were written to set the record straight about what Mies did wrong, what her career was like as a nephrologist in Chicago, what her family was like. It feels like the memoirs are an accounting of her various conflicts with the world. She wrote them, of course, looking back. She didn't write them along with the lived experience she was going through.

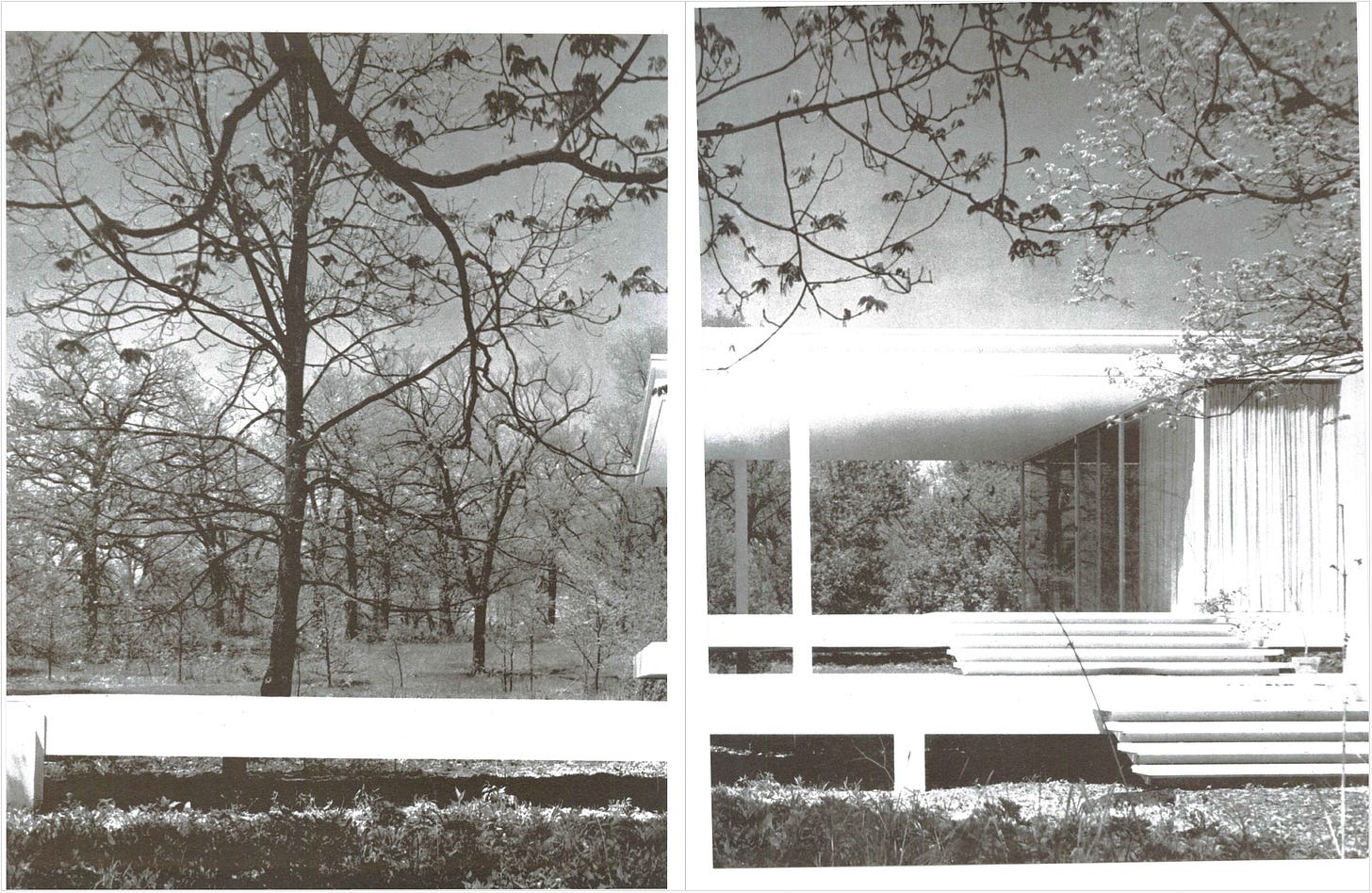

When I wanted to understand what her lived experience was like in the house, I really had to turn to her poetry. She writes a number of poems that describe the way the light was coming through the glass, that describe the wild confrontation with nature. She's talking about life and death, and things flying into the glass, and dying below the house, and her poodle eating the remains of birds and little rodents… I think it was really her poems that helped me get this vision of what it was to live there. There's this perception that, "Oh, she hated the house, and she hated the architect,” but she actually countersued him to keep the house, which I think people miss, that the lawsuit was really him suing her, and her countersuing to keep the house.

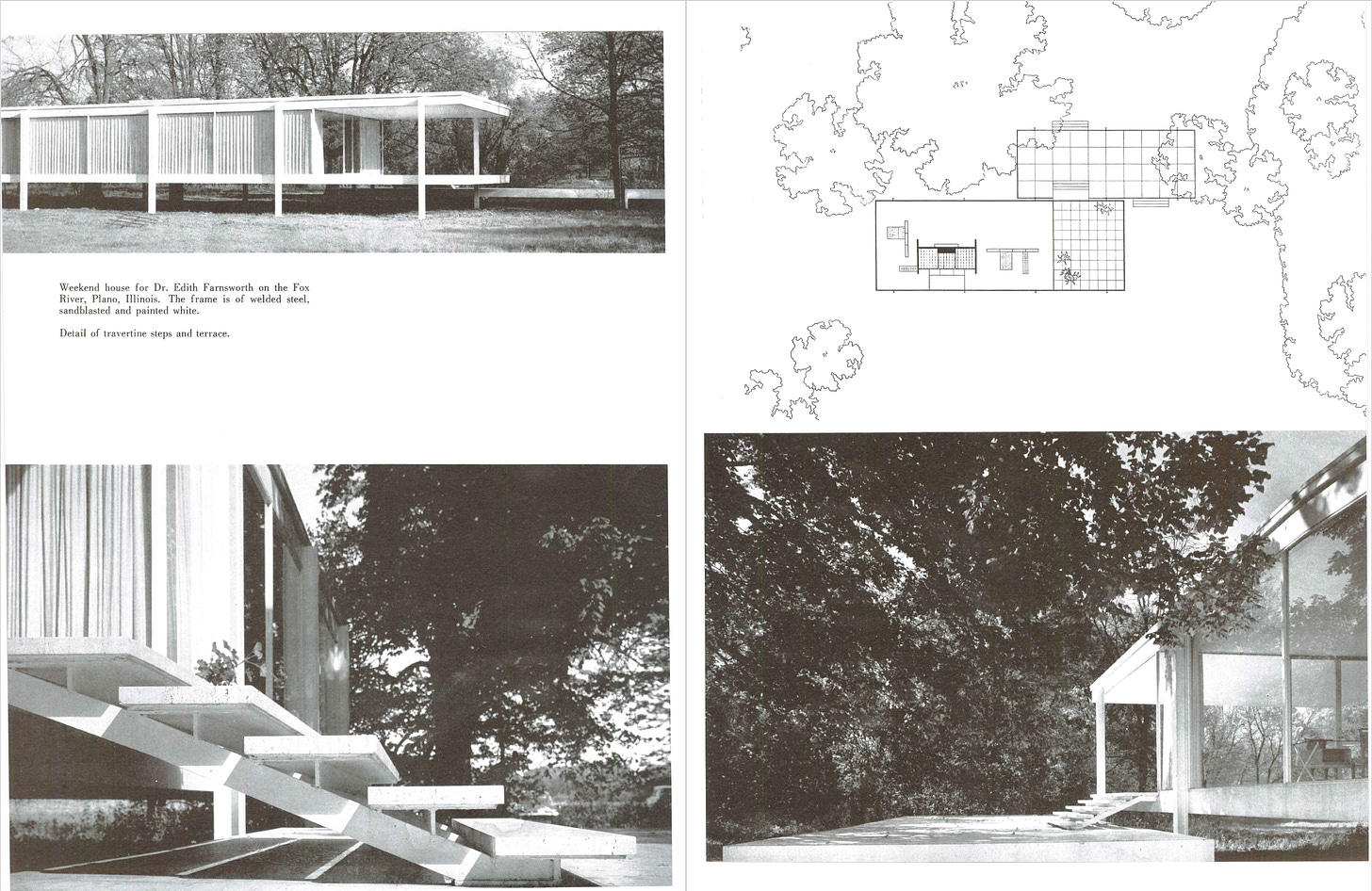

She stayed there for another, I want to say, almost 20 years. She would go out there Wednesdays and weekends for almost another 20 years, which you don't do if you don't love a place, because it was not that easy to get to, especially when she first started driving there. She really fell in love with that location. She chose it, of course, before she chose the architect. It was right on the Fox River, which it had a very tumultuous relationship with, because, of course, even during construction, the river flooded up to the floor of the house, even though the floor of the house was five feet above the ground. I can imagine and glean from the poetry that living 100 feet from this Fox River in the floodplain, in a glass house, open to the elements, and whatever else, it was a bit of a heightened, dramatic, but beautiful experience. It was kind of like camping in the same sense, right? The only thing separating you from whatever is going on outside is this little pane of glass. It wasn't even double-paned glass. I think she lived for that dramatic experience of nature.

Scott Mehaffey, who's the director of the Farnsworth House, helped me get access to some interviews they did with some of her neighbors who had known her. They understood she was a bit eccentric, but they seemed to really appreciate her. She would have the neighbor kids over, and make them lunch, and make them listen to her play violin, and force them to learn French. She was this eccentric auntie figure, I think, to the folks in the area who had lived there for generations and were farmers. I think she, as much as there's this vision of her as this solitary figure, I think she was quite solitary by choice. I was excited by the poetry, because I think she found a lot of joy in her solitude. I don't think there are a lot of examples of that in history, just pausing and acknowledging that a woman is finding a lot of joy in solitude, and finding a lot of creative energy in solitude and in a beautiful place.

I really like this idea of history that can engage in these very immediate sensory moments. I think that's something architectural education did to me. It made me really think about the material of a scene or a situation. It really informs my writing. Yes, that to me was a really powerful thing to switch from this whole writing about her conflicts with the world, to just her being in one place, and being in this house, because she loved it. That, to me, is maybe the point of architecture.

Laura: Did her poetry influence your own writing?

Nora: Oh, I would say it did in glimpses. There was here and there a line, or a stanza that just floored me. There's this line, "If we were quiet, we would hear ourselves as electric dust." I mean, what is that? That's phenomenal. Sometimes, it was a bit of a challenge. I would say, not in their wholeness, but really there were glimmers of them that really shook me and made me marvel. I think that's what I really loved about her poetry is that, maybe the whole poem could be a bit formal, or a bit stale, because she's really trying to work to convey something in the poem, but somehow, there would be a twist of a phrase like that.

I don't know, there were these moments that really stunned me. I think it's because she did read a lot of great poetry. I think it really did absorb into her own poems at certain points. Really, it was more about like a turn of phrase, or an acknowledgment of the watery light coming in through the window, things like that, really in the detail.

Laura: I think that your use of her poetry in the book is done incredibly well, because it comes across that her poetry is pretty great. You don't get the sense—I didn't get the sense, at least—that they were long and more formal pieces, which makes sense for the era that she was in. The way that you pulled them out and teased them through the text is really beautiful.

Nora: Thank you. I really fell in love with them. I wanted to do them justice. I don't want to publish an entire poem, and have people miss the glimmer of the soul of this poem, because there was always a beautiful soul in it somewhere that I could find.

Laura: It seemed to me that, at least from what I got from your explanation, her memoir was fragmented and non-chronological. Did that influence the form of the book?

Nora: Absolutely. When I realized that's what was going on, it gave me this incredible permission to think in a similar way in my book. I started writing things, and eventually, got to deciding to just put the book in chronological order, in terms of the research. I think that putting it in chronological order in terms of the research allowed me to take moments of casting back into the past, in similar ways that she did.

She would always have a chronological framework, in that, she was like, "This is the chapter about me being born, and being a child." Then, the chapter would also start 30 years before she was born, and Chicago is burning down, and her mother is fleeing Chicago in the fire. I thought, "God, what a wild way to begin your own memoir with a fire that precedes you by a generation." I think because she saw herself maybe as part of, or built by these forces, yes, it came across as non-chronological. She really does approach it more like a writer than like a strict biography of a person that would just indicate what they did and where they went. It gave me permission for sure. It made me feel much more able to experiment with time.

Laura: One of the things that you constantly talk about is glass, and obviously, this is a glass house. I was wondering why do you think that glass is so seductive, and so appealing to us, and to her, and why is this house so seductive?

Nora: Oh my gosh, that I'm still unpacking. I think, in the modern era, when her house was being built, and when Mies van der Rohe was making his glass architecture, I think it was this post-war promise of transparency. Glass is a couple of things in architecture. It's very transparent. The idea is there's nothing hiding. You can see it all. In order to pull that off, you have to be, as an inhabitant, you have to be living in a very austere way, right? My God, I can't imagine if my apartment had glass walls, I have piles of books everywhere, it would be so embarrassing. I think there's this way in which modernism brings glass in as a promise of transparency and seeing everything. There's a sort of, I don't know, social contract in that, you're not hiding anything.

At the same time, there's a violence inherent in that, which is that “I am powerful enough to live in a glass house. The power I have means I'm not vulnerable. I'm in a glass house, but I have no reason to be afraid.” In my mind, you have to be very secure. I don't know if "violence" is the right word, but this house is built in the US at the same time that we're experimenting with atomic bombs. We're becoming the only nation that could literally destroy the Earth at this moment, right? Having that violence ensures "a safer world" because, of course, you can trust the most violent nation on earth to keep things peaceful. Oh, wait, not really. It struck me as something bizarre. You're building a glass house at a moment when the US is ensuring that it's going to be able to "ensure peace" by having the most violent weapons. I don't know if there's more there that I need to unpack. I think there is. I'm really curious about this relationship between very vulnerable architecture like glass houses, and violent states like the US having this world-ending power.

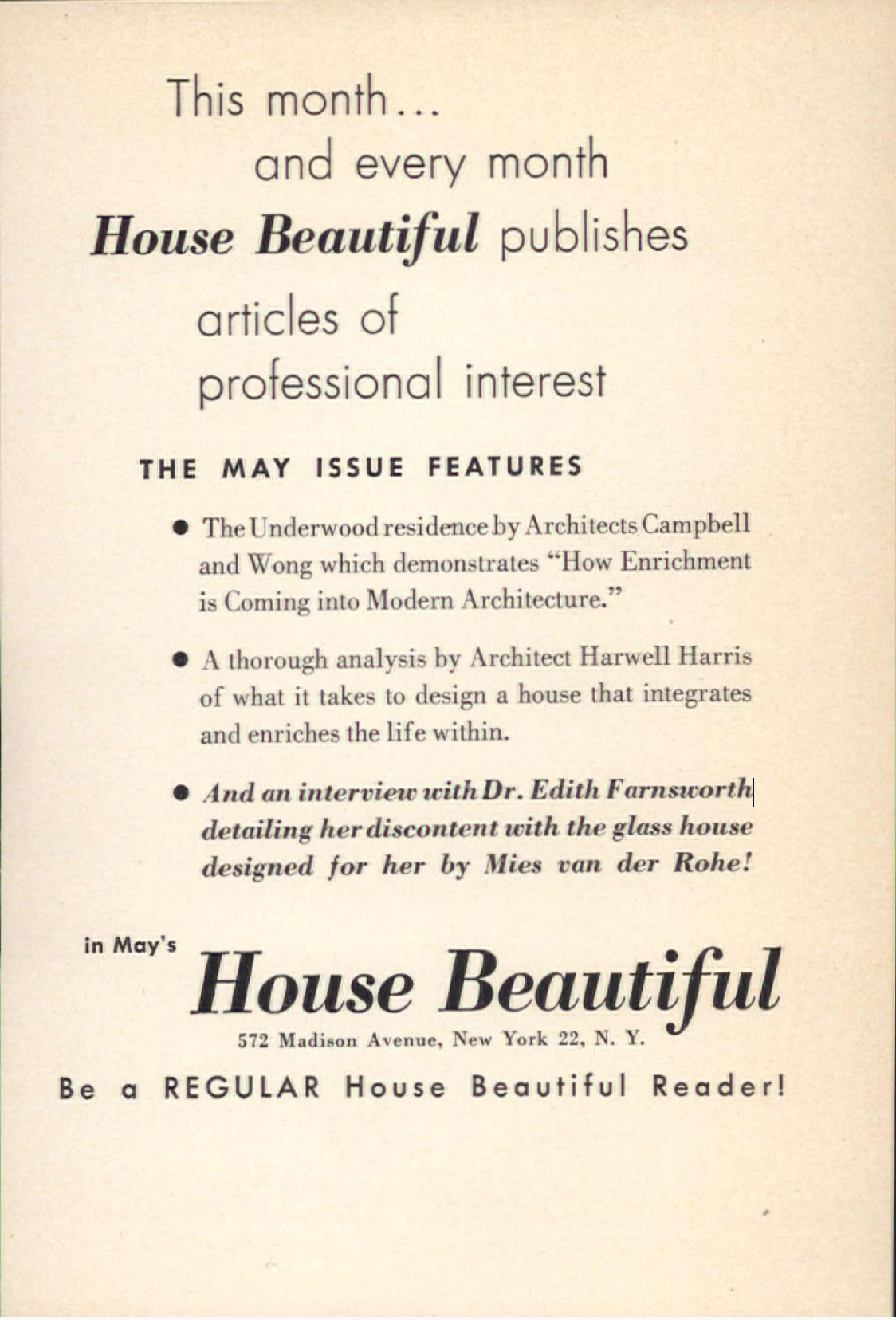

I want to keep exploring that, because you're right, for centuries, it's been something that's been sought after and protected in various ways. At the same time, when it becomes part of architecture in modernism, the House Beautiful editor Elizabeth Gordon saw glass houses as an example of democracy being under attack, because your entire life would be on display and you couldn't buy things, which is the height of communism and anti-democratic principles.

Laura: I think it's interesting that houses like the Farnsworth House and [Philip Johnson’s] The Glass House—all of them from that era are still so venerated and they're still so influential in terms of how design people want to live. Could you talk a little bit about the impact that the Farnsworth House had when it came out and why is it still so important?

Nora: It had a really remarkable impact. The house was finished in, I think, August or September of '51. Right after it came out, the architectural press said, "This is one of the most important houses of the 20th century. Mies van der Rohe is a genius. This is really one of the most important houses done in the US." It was his first completed house commission in the United States.

It was a really big deal for Mies to get this commission. It was a really big deal for it to be designed the way it was. It was truly a groundbreaking design. It wasn't until, I think, 1953, so maybe two years later, that House Beautiful editor Elizabeth Gordon came out with this notion that it was a threat to the next America, and a threat to democracy.

The architectural press… were always supportive. In the bigger picture of House Beautiful and press about domesticity and housing, it was lambasted. Elizabeth Gordon was very close, of course, with Frank Lloyd Wright. Frank Lloyd Wright loved Mies being disparaged in the press because, of course, Frank Lloyd Wright had his version of modernism, which he decided was American. Any kind of European modernism that would appear in the US would be a threat to that. In a way, it was orchestrating this as a way to steer public opinion back toward Frank Lloyd Wright.

I think whether you're seeing it as the best example of modern architecture, which Architectural Forum did, or a threat to democracy, which is what House Beautiful was saying two years later, after it was finished, either way, it's making a huge impact. Whether we think it's threatening and weird, and an example of European modernism taking over the US, or whether we think it's the best example of American housing, or an American house, it makes an impact.

I think at a certain point, it does surpass its architect. It just is a remarkable piece of architecture that people enjoy visiting and respond to because it is singular—there aren't many houses like that. I think it's also an example, and we have so few examples. I think the National Trust has around eight properties that were commissioned by women out of all of its holdings. In a way, it becomes this really significant house because it's a remarkable piece of architecture, but also because it was one that was commissioned by a woman.

Laura: After publication, do you feel your research on Edith is complete, or do you still feel, I guess, almost enmeshed with her?

Nora: I guess I could put it this way: For the first time in a long time, I'm looking at my bookshelf, and all the binders about her… I'm ready to move them to the closet. I'm not ready to throw them away, but I'm ready [chuckles] to move them.

I feel like the project is complete. That I wrote what I wanted to write, I learned what I needed to learn. I got to share the things I felt I wanted to share. Glimmers of her may likely show up in future projects. I think that's inevitable. I don't feel like I need to write a sequel to the book, or I don't really need to dive back into her biography.

Laura: How does it feel to have it out in the world? Because some of it is so intensely personal as well.

Nora: It feels good. The responses I've gotten have been really interesting. The other women have come up to me and said, "I experienced the same thing at my institution, at my school. I was terrified to share any of this because of the institution-threatening messaging." It feels good to be able to just write my lived experience. It's been interesting: I've had people who approached me who are a generation older than me, who have said, "Reading your book made me want to write about my experiences." I think that we should.

I think it was Anne Lamott [who] said, "If you don't want me to write about how you've treated me, then don't treat me badly." I feel that, if you're going to be abused by an institution, if you're going to be harassed by somebody who's writing a book and wants all of your research and wants to put you in a footnote, then I think you should write them into your book. Screw them. If somebody means you harm and means to erase you or displace you, then that's on them. It's your story, and you're allowed to write about your lived experience. All of the silencing and holding narratives back only allows institutions and individuals to perpetuate that violence against other people. I think if institutions and individuals are concerned that writers are going to write about them, then maybe they won't treat people badly. If you're treating your employees badly, I think everybody has a right to know. If you're going through a horrible experience at an institution, please write about it. I'd like to know that so that I never consider lecturing or going to that institution or working there.

In my book, I did not name individuals or institutions intentionally. A lot of that was because I didn't want people to get hung up on the particularities of the place, because I think a lot of the things I wrote about were really common experiences for people. I kept things at the typological level so that someone could maybe not get lost in the particularities. I recognize that you can look at somebody's CV, and it's pretty easy to tell where they experienced something. I'm not protecting an institution, but I thought, maybe by not naming it, I allow a reader to feel this sort of universality of these things. In the end, it's not really necessarily about attacking any one place or any one person but acknowledging that these are things that happen to women and femme folks and people of color and trans folks frequently at institutions.

I think it is important to write about them, because otherwise, we just wonder like, "What happened to that woman? She used to teach here. She was really nice." That happened to me a lot in my education. There were women who just disappeared. They were my professors, and they suddenly disappeared, and I was like, "What happened to so and so?" Then I would learn a decade later that they weren't granted tenure for political reasons, or that they were harassed out of an institution.

I think by not naming that violence, we perpetuate this narrative that women aren't cut out for these difficult professional roles, but we are. We just like trans folks, people of color, immigrants. There's this constant violence and institutional violence against people whose identities are not perceived to be neutral, who embody things that are not perceived to be "professional or neutral," like a cisgendered White male is never perceived as a threat in the classroom the way a woman is, or a trans person would be, for example. I thought I really need to write about these things because this is maybe the moment to be naming those things. I think by not naming them, we just open ourselves and our community up to more violence. Yes, it was scary, for sure. It was scary.

Laura: What has been the reaction from men within this very male-dominated world of architecture?

Nora: The first review I had was by a man. The review was by Dan Roche for Architect's Newspaper. In parts of the review, he writes that he was horrified. I think that maybe men don't realize what we're all going through because we smile and push through the day. Like you said, you can't have a breakdown, you have to just keep teaching your class or whatever, even though inside you're just absolutely having a panic attack.

At least the men I've spoken with have expressed surprise, shock, genuine disgust, and empathy. I think that that's really critical, because I think that we need men, in particular straight men and straight white men, to be vocal about this dehumanized experience that all the rest of us are having at institutions. I think until straight men, and in particular straight white men stand up and say, "Enough is enough. This is unacceptable. We can't be treating people who are not straight men like this at these institutions," until they're part of the struggle, I don't think we're really going to get anywhere. We live in a country where women aren't even seen as fully human. I would just argue [that] if we can't make medical decisions for ourselves with our doctors, then we're not really fully citizens in this country. I think until men step up, we're really not going to get anywhere because we're not really heard.

I think that one of my goals of the book was not for it to come across as a bashing of men and a bashing of the architect, because I really don't have a problem with men at all; I have a problem with patriarchal institutions that abuse anybody who's not a man. A lot of my mentors are men. I think, because it's a male-dominated field, some of my closest colleagues are also men. They've been, yes, incredibly supportive.

I think being honest and sharing one's lived experience and trusting other people to read that lived experience and respond to it maturely, yes, it's a risk, but I think it's a risk worth taking, because their responses of shock and disgust are warranted and they're needed on a larger scale. I think maybe if we started on the small scale of just sharing narratives of what's happened to us, it really helps.

Laura: What do you want to leave people reading this with about Edith and the Edith Farnsworth House?

Nora: I would encourage people to go visit the Edith Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois. It's a remarkable place. I created a lot of photography related to the house because I was curious about the absence of images of [Edith] in the house. One of the things I did for the book was use my own body as a proxy. I photographed myself in the house. There are two particular bodies of work that I did that I find interesting. One where I wore a dress from the 1940s, which would have been the era in which she commissioned the house. I sit in the house and photograph myself from the outside. Portraits of looking into the house. Then another body of work where I wore a coat, a pony coat, literally made of horse, that a great aunt of mine owned. I photographed myself outside of the house wearing that coat as a way to bring my own family history of unusual women to bear upon this history of an unusual woman.

I think, for me, the book contains both the textual archival history, but it also contains the production of new pieces of photography and art that were a way of getting closer to understanding the lived experience of this place. I just wanted to acknowledge that, because I think photography as a medium was a way of thinking about this glass house because it was so frequently photographed.

In particular, self-photography was important because it was a way of writing and imaging a woman's experience back into it, which was not authentic. It had to be very constructed. I had to get permission to go into the house and get permission to photograph myself outside of it. I really enjoyed that process as well. I think it was something that was unexpected and unusual for a writer to do but allowed me another layer of understanding of that place. To position my body in the house and to photograph it multiple times over a series of days really lent me a different way of understanding inhabiting that space.

I think I was drawn in by Edith's story, but I think what I didn't recognize until you said it was, I was really seduced by the house as well. It's a seductive house.