When I added the footnotes to this piece, Substack marked it as “too long for email.” I’ve had this error message before and managed to cut-down to fit, but going forward I will likely try in-text citations. For now, please email me if you would like to know the citation for any quote or information in this newsletter.

- Laura

If you follow my Instagram, you might have seen the short post I wrote in memory of Nino Cerruti, who passed away this week at age 91.

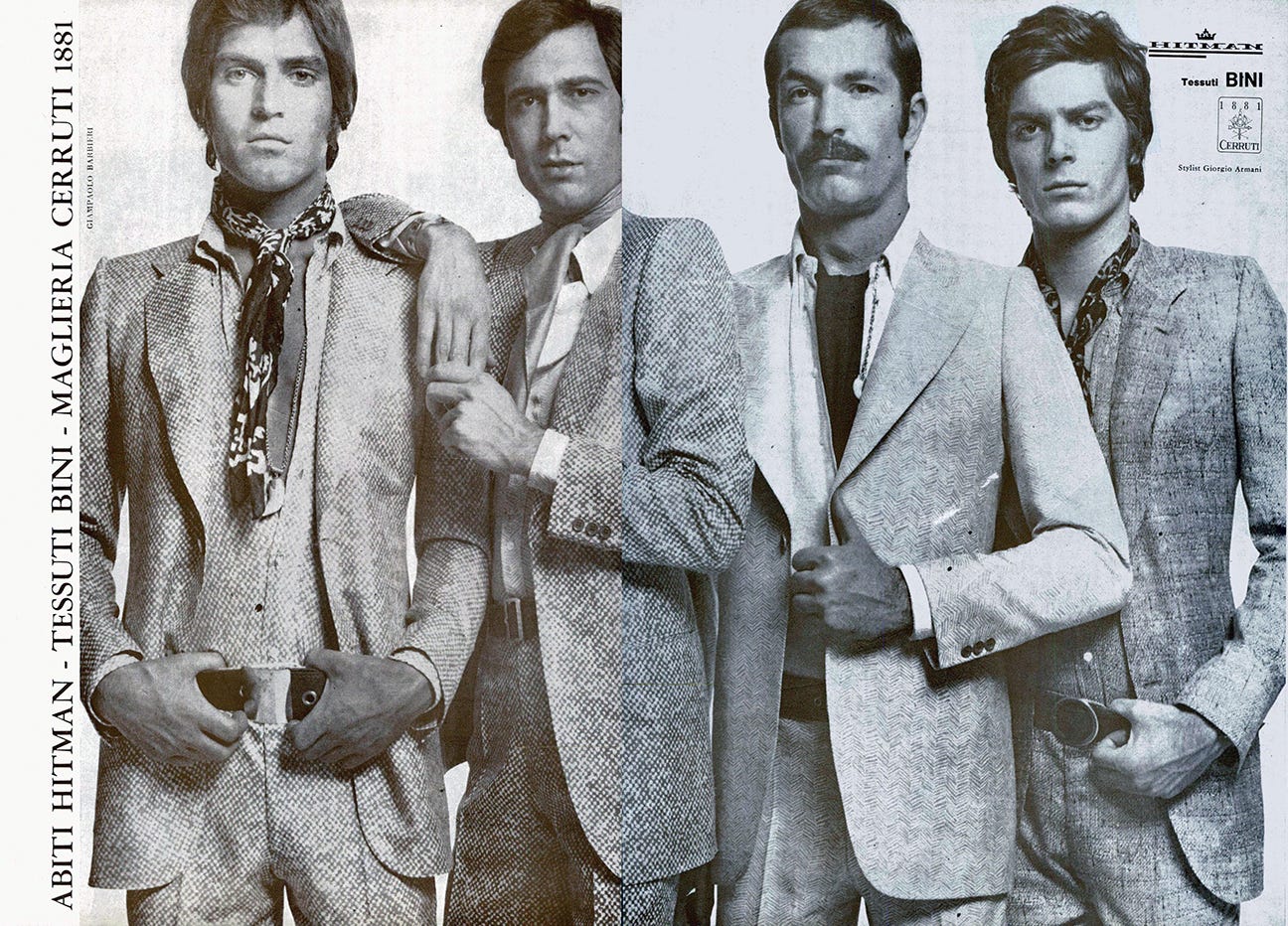

Textiles were in his blood—his grandfather had founded Lanificio Fratelli Cerruti, a luxury textile mill, in 1881. Based in Biella in the Piedmont region, they were known for their very fine woolens. Cerruti said of his childhood: “I started working when I was very young. I was only 11 years old when my father started me in the factory. That was the stipulation he made to earn my summer holiday.” Antonio (Nino) had just his first year at Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore when his father suddenly passed away, leaving him in charge at age 20. It was 1950 and Nino stepped easily into his new role: “Because the first business of my family was fabric—fabric taught as a fashion item—I have always been living in this kind of world.” He set to work expanding the reach of their textiles within the fashion industry, eventually leading him to establish their first menswear collection, Hitman, in 1957. “Dedicated to creating sartorial elegance on an industrial scale,” Hitman was part of the nascent ready-to-wear industry that revolutionized Italian tailoring and fashion. Cerruti set up a factory outside of Milan to produce the Hitman suits, as well as manufacture tailored goods for companies that were longtime clients of the woolens. In 1964 he gave Giorgio Armani his first design job, straight from working as a merchandiser; under Nino's tutelage, Armani learned how to design. He worked for Hitman until 1970, when he left to found his own company.

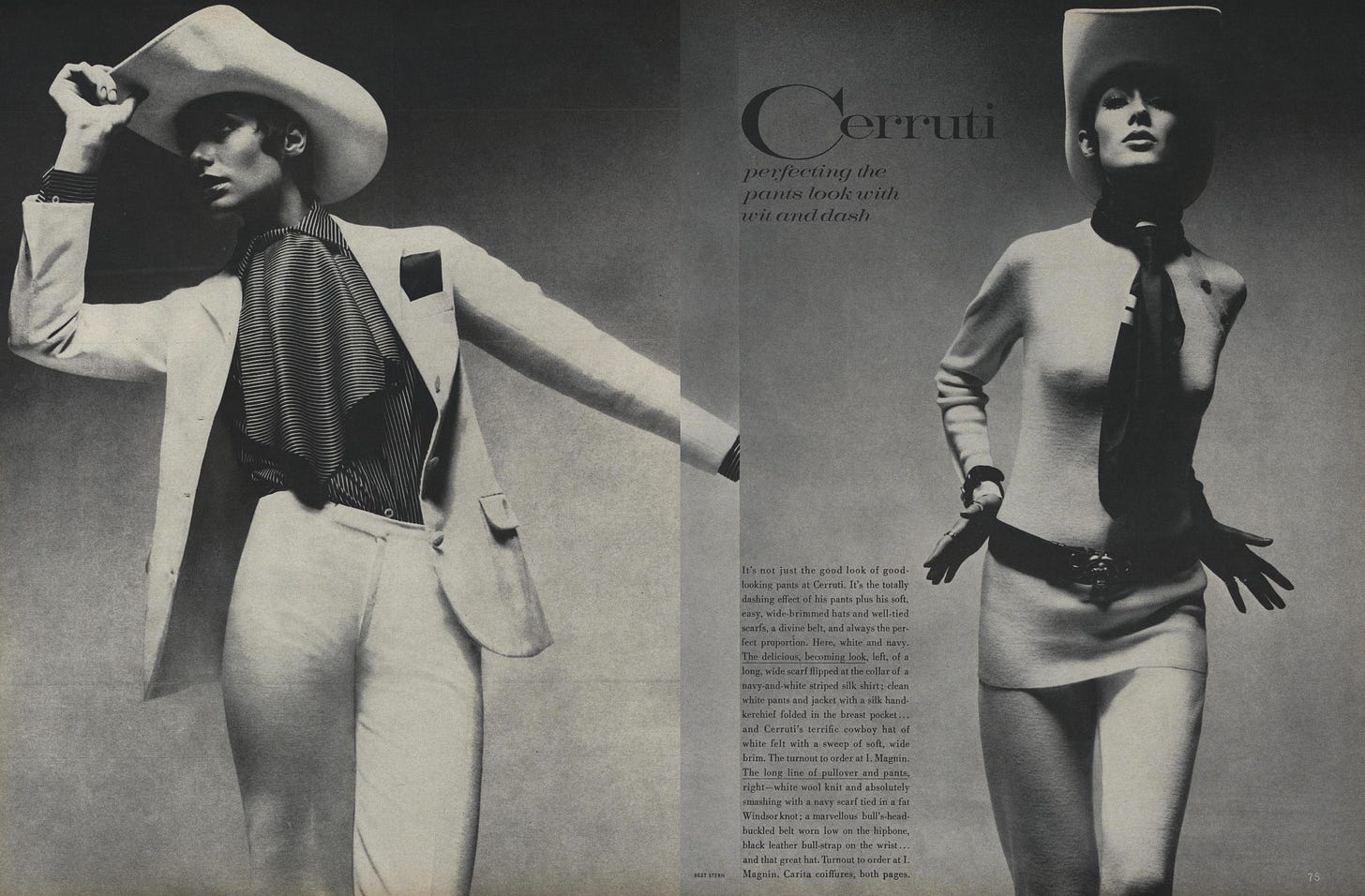

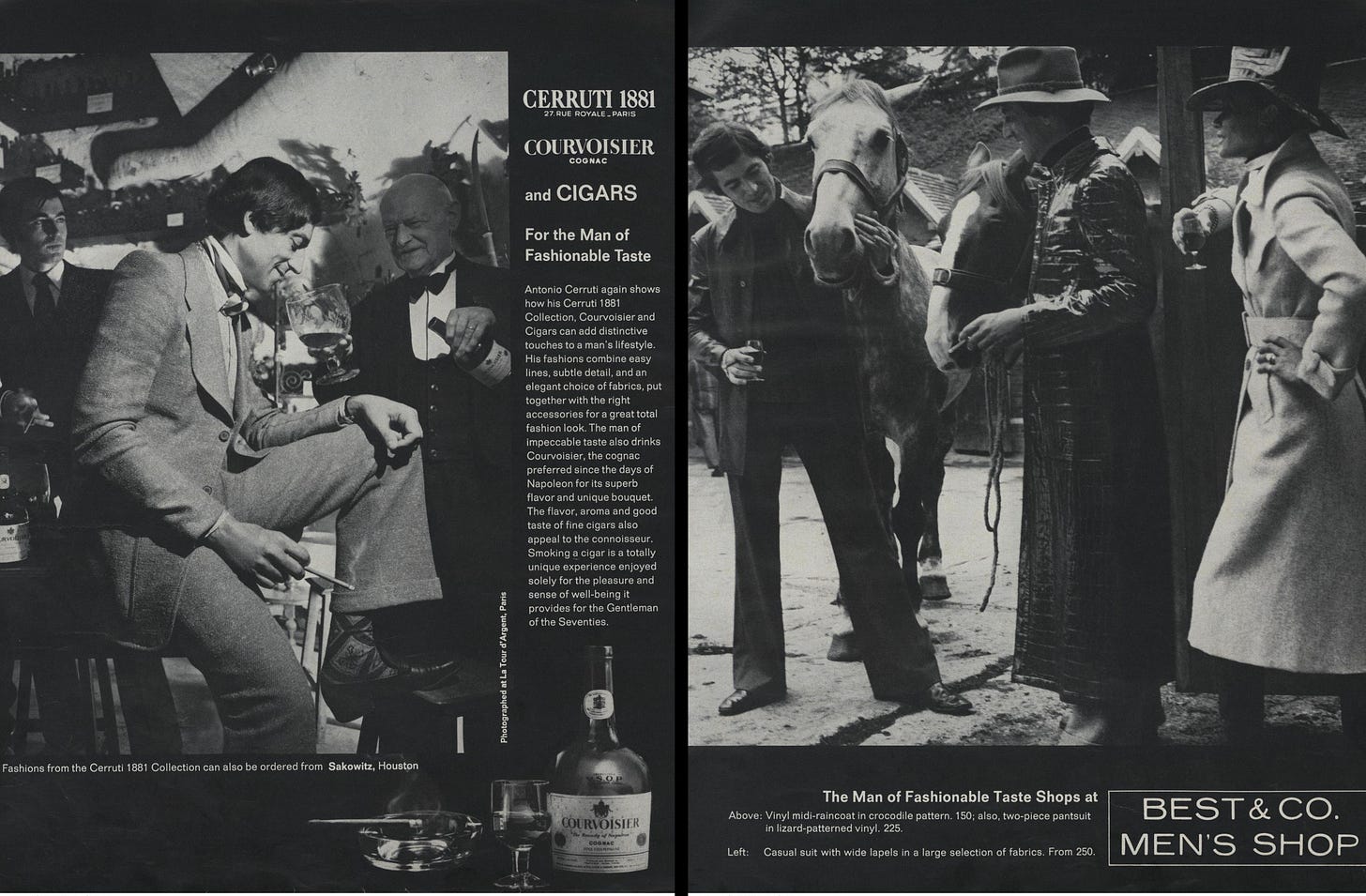

Highly successful, by 1967 Nino was ready to take on the international fashion scene. He moved the Cerruti headquarters to Paris (the mill and factory remained in Italy) and opened a store at 3, Place de la Madeleine. Described by Vogue as “the biggest and best new men’s shop in Paris… a super-luxe mecca for beautifully cut clothes and accessories in excellent fabrics,” it was designed by Vico Magistretti over three floors with a modern, all-white interior, tobacco-colored carpet, tobacco leather and silver showcases. It was so modern that IBM designed an early computer-ticketing system to keep track of the 2,000 suits in stock. Under the name Cerruti 1881 were luxe couture suits, while Hitman’s RTW suits were available for a less-expensive price.

The same year Cerruti 1881 became a member of the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode. While menswear was what they were known for, Nino designed couture collections that included both. In addition to luxurious evening wear ladies ensembles, he also duplicated all of the men’s styles for women—similar in practice to the likes of Rudi Gernreich’s unisex garments, though Cerruti disliked that term. He remarked, “My clothes are for the woman who leads the same kind of life as a man, an active life. Lots of women’s fashions come out of men’s wear. I have a basic philosophy: Simpler clothes are more sophisticated. It’s a masculine way of looking at things.” Styles like knit long tunic and matching slacks (worn with Nino’s favorite silk scarf knotted at the neck) effortlessly worked for both sexes, establishing a sleek, pulled-together look.

With Cerruti 1881 Nino sought to achieve a style that was up to the minute yet not futuristic (unlike his contemporaries Cardin and Courrèges)—“new in style, but not questionable… above all; nothing to make a man look odd”—a goal that stayed with him throughout his career. Very quickly Cerruti 1881 became the place to go for subtly sophisticated tailoring, amassing a clientele of the chicest men in Paris—among them Jean-Paul Belmondo and Alain Delon. Even Gabrielle Chanel purchased a pair of his black men’s trousers. In 1969 Best & Co. received the exclusive New York contract for Cerruti with department stores around the country following. Partnerships with American manufacturers followed (Society Brand, M. Wile & Co., Gleneagles, and Hart Schaeffner & Marx), allowing for the dissemination of his ideas into the mainstream.

Handsome, tall (6'3) and fit, he was the perfect model for his style of easy, international, understated glamour. Intellectual, he was described as “adventurous with a razor-like mind honed by consuming interests in everything from modern technology to ancient art, skin diving to gardening, and with a quick humor that flashes out in whatever he does.” He told a journalist in 1975 that he loved “everything good… good opera, good theater and good food,” and he was also known as an obsessive movie fan. Running a textile mill, a fashion company and manufacturer with several stores, along with designing numerous collections for other brands, it can be easily stated that Cerruti was a workaholic—in the mid-70s he spoke about this work obsession: “Not too long ago I went through a mental depression from working too hard, I had to change my work habits and attitudes, Now my philosophy is—I do my best and if it doesn’t work, what can I do.” He was similarly philosophic about his day-to-day life: “I hate to form favorite habits. When you have too many habits you start dying. You must keep an open mind to accept new things. Life is too short…make it as complete as possible.”

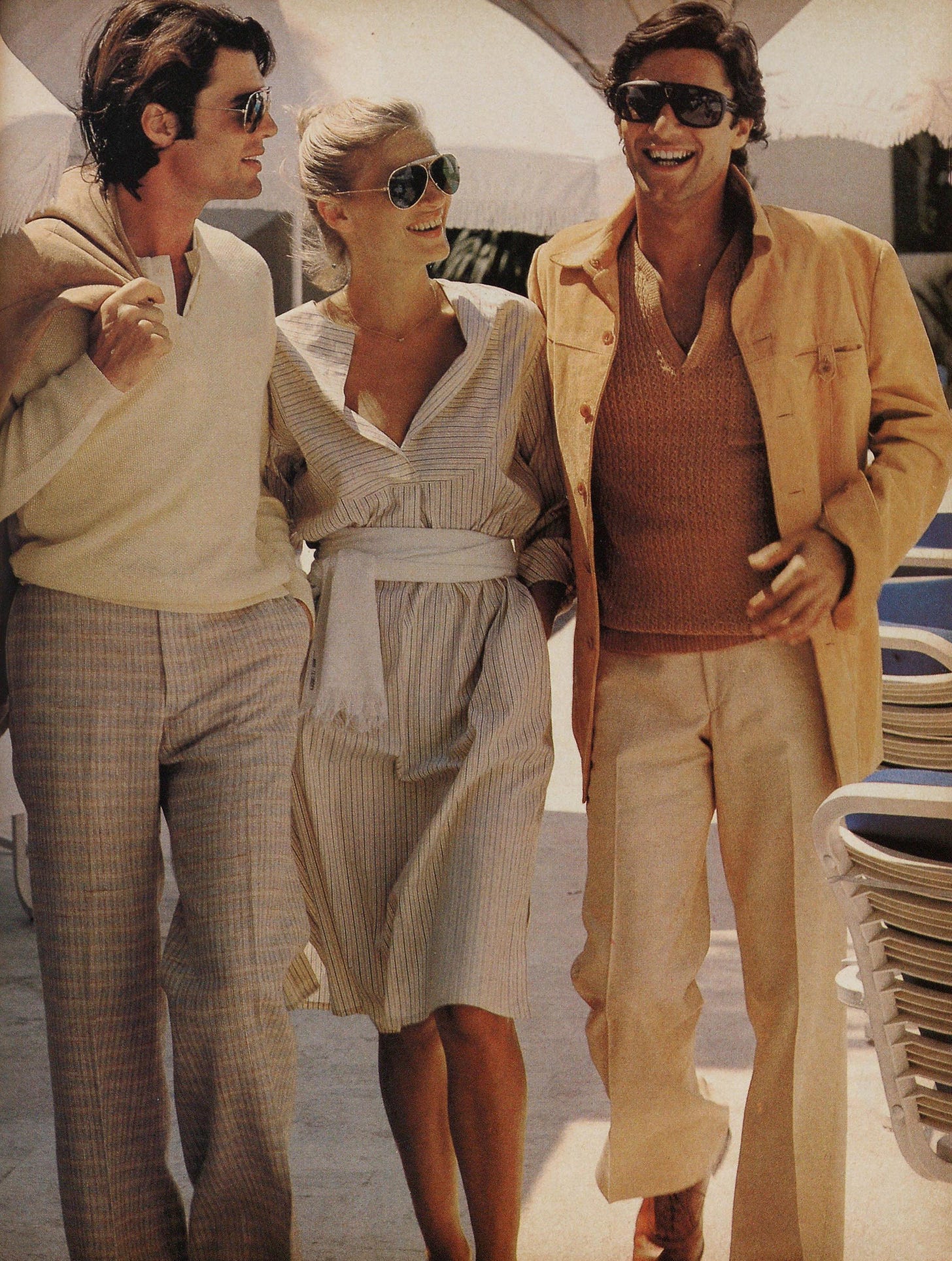

A king of timeless classicism, Nino was always conscious of new developments in dress on the street and the interplay of that with the traditions of the past. He said, “Fashion is a continual exchange of ideas and environment and is close to the society around us. The professional designer must be aware of his own and of other cultures,” though at the same time he admonished the “boy scout attitude” found among American designers that led them towards “uncultivated” cultural appropriation. Instead he felt that the culture reflected a greater interest in leisure and sport: “We are constantly absorbing fashion from our leisure time into our daily lives and it’s necessary to create new and different leisure wear—for an active city life as well as weekends.” To fill this void, he included knits and leisure looks in his main collections before launching Cerruti Sport in 1977.

A philosopher about clothes, he spoke with insight about dress, identity and the industry: "Fashion doesn't have to be a continuous trial of something new. Always shock. It doesn't have to be like a punch in the eye. But more like a caress to the face. We are approaching that moment in time when we are ready for the subtle change—without going back to the subdued. When fashion will mean the right balance of elements, the right colors, the right proportion. It is a much more delicate thing to achieve, and requires more work. But is more sophisticated… People think sophisticated is boldness, that it is daring. True sophistication is subtlety.”

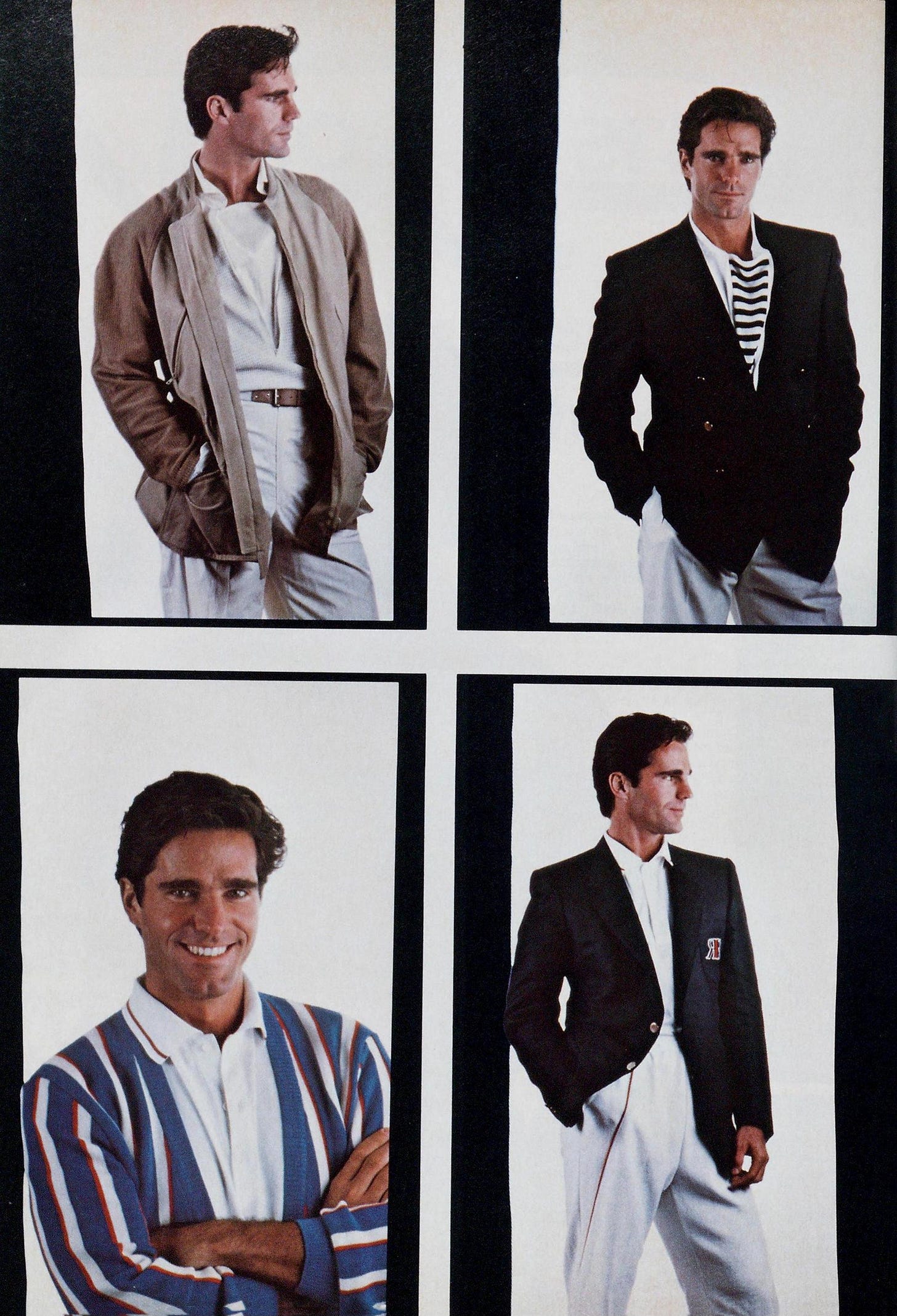

Throughout his career he sought ways to modernize traditional dressing; in the early 1970s he slipped sweaters under unlined cashmere jackets or wore cardigans over sweaters in what the press described as the “layered look.” Continuing this elegant subversion in the 1980s (though formalwear, dress shirts and suits still accounted for over 60 percent of Cerruti’s menswear business), he focused on the concept of what he called “casual chic”—“in essence, he began to break the rules of constructed clothing, providing alternatives such as turtleneck sweaters and polo shirts as substitutes for dress shirts with tailored clothing, eliminating the need for a tie.” As he explained, “Casual chic takes the best from sportswear. it is a concept of mixing luxury items with practical, comfortable clothing.”

Cerruti softened men’s suiting starting in the mid-70s (as his protege Armani also memorably did), before later in the 80s finding his sharper edge again. During his career he won the 1982 Cutty Sark Outstanding International Designer Award, the 1984 Gentleman’s Quarterly Manstyle Award and the 1985 Pitti Uomo Prize given by the Italian government. By 1987 Cerruti 1881 was worth $135 million.

Due to his celebrity clientele, it’s no surprise that Nino found a fourth career designing costumes for films. Sometimes the male stars simply wore Cerruti suits, while other times he created whole wardrobes. His earliest work onscreen was for Belmondo in 1965, and in 1968 he made Faye Dunaway's straw hat for Bonnie and Clyde. Among his earliest cinematic designs were for the controversial French erotic drama Story of O (1975). In the 1980s he went on to outfit on screen the men of Miami Vice, Jack Nicholson as the Devil in The Witches of Eastwick, Michael Douglas in Fatal Attraction, Charlie Sheen and Douglas in Wall Street, as well as Kathleen Turner in several films (Jewel of the Nile, Julia and Julia, Switching Channels, and V.I. Warshawski). Equally memorable were the suits he created for Richard Gere in Pretty Woman, Michael Douglas in Basic Instinct and Robert Redford in Indecent Proposal. By the time that Rizzoli published a book on his costume designs in 1994, Cinema: Nino Cerruti and the Stars, he had amassed over 130 contributions to movies, stage and television. Forgoing the flamboyance of much costume design, Cerruti sought to make the costumes so much of the character that they became almost invisible: “If you compare how people were dressed before the war—it was a very rare film when they were not glamorous. Now films have to be not about myth or heroes. There are a lot of social implications. There is an attempt to destroy the dignity of human beings. What clothes have to emphasize is character.” Cerruti’s costumes work precisely because you come away from the movie thinking more about the character than the clothes—though his costumes definitely had impacts far beyond the movie theatre. So centrally did he define the idea of a powerful 1980s male that when American Psycho was made in 2000, Cerruti designed Patrick Bateman’s immortal suits.

After fifty years of running Cerruti, in 2000 Nino decided to sell a portion of the business. Nino sold his 51 percent stake in Cerruti 1881 to the Italian company Fin.part for $70 million. At the time he revealed, “Fashion has become complex and costly. You need to have capital to grow, and our cash flow was insufficient. We are living in a world where you cannot stay in the same place. Either you develop or you disappear.” Lanificio Fratelli Cerruti was not included in the sale. When the sale was announced Nino was supposed to stay on as artistic director and president, but the relationship between him and the new owners quickly soured due to different ideas about how the company should be run. Within a year Fin.part purchased the remaining 49 percent from the Cerruti family, quickly announcing that Nino would no longer have any day-to-day responsibilities at Cerruti. He showed his last collection in June 2001, after 34 years. Fin.part laid off 32 of the 90 employees at the Paris headquarters in March 2002, leading Nino Cerruti to publicly complain, “They’re driven it into the ground…Their conduct is incomprehensible to me. Some of those people had been there for 15 years. I built the house on human values, which have been abandoned. They’re ruining the house’s heritage.” Nino continued to run Lanificio Fratelli Cerruti and in 2002 he purchased the interiors company Baleri Italia, shifting his focus from the body to the home: “As I did with my fashion, I always ask myself, ‘What do people want?’ I am interested in the real home for real people.”

A man of exquisite taste and elegance, Nino Cerruti was truly a designer who designed for how people (in particular, men) really live. He elevated the everyday and the mundane, yet never designed styles that overpowered the person. His designs were for the actions of day-to-day life—the office, meetings, parties, relaxing—but done with such a subtle sophisticated chicness that they are totally timeless. Other menswear designers might have created more fabulous, eye-catching and revolutionary looks, but few have had more impact on the dress of man at large.

There was a time when 'Cerutti 1881' meant the fabric in your suit was top notch; my wedding suit in 1993 was made of Cerutti fabric, a gorgeous Super 200 in blue. And as I noted on your Instagram, my big brother was transitioning from session musician to music production under Giorgio Moroder in the early 1980s, and I remember his pride buying his first proper suit - a Nino Cerruti in tan with subdued disco style - modestly wide lapels and a slight flare in the leg. I reckon if that suit were chemically analyzed it would be 50% cocaine! The stories of Moroder's recording studio were wild.