With Her Own Hands: Women Weaving Their Stories

An Interview with Nicole Nehrig on her New Book

“Women’s lives, their identities, their internal experiences have historically been hidden from public view. But the textiles they created offer a glimpse into their world. It is with thread that women wrote.”

Spanning millennia and continents, With Her Own Hands: Women Weaving Their Stories is a new book that studies how women have created meaning through fiber and textile work. Clinical psychologist and avid knitter Nicole Nehrig takes an expansive look at textile work—eschewing chronology, she seamlessly weaves together different time periods, cultures, and academic disciplines to show how eternal the importance of textiles has been in women’s lives. Each chapter focuses on a potential source of meaning in life and how weaving/quilting/embroidery/sewing/etc. contributes to that meaning making; these sources of meaning include “the ability to fully engage in the life cycle, to develop and express intellectual abilities, to craft a self through creative practice, to experience and process complex emotions, to have meaningful relationships and a sense of belonging, to feel that your contributions are valued by others and that you have some ability to improve your circumstances, and to stand up for what you believe in.”

It’s a truly all-encompassing project, one that truly seeks to illuminate what is at the heart of textile work. While many women, historically and today, had little choice in whether or not they spun, wove, or sewed, as Nehrig points out, “we can choose to find value and significance in the experiences available to us.” More than just pieces of cloth, textiles have been used “to express political protest, convey coded messages, record historical events, transmit cultural ideology, process traumas, earn an income, celebrate, and mourn.”

As I’ve been packing and organizing for a move, I’ve been in close communion with many examples of the textile arts of daily life: racks of homemade vintage clothes, sheaths of vintage sewing patterns, family heirloom quilts, and too many unfinished needlework projects. The work of women—some my family, some unknown, some hobbyists, some professionals—all who found in textile work some of the meaning that Nehrig outlines.

With Her Own Hands: Women Weaving Their Stories (W.W. Norton, 2025) is available from Bookshop, Amazon, and wherever books are sold.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Laura McLaws Helms: Can you tell me a little bit about your background and how you became interested in knitting, fiber arts and textiles?

Nicole Nehrig: It was really happenstance. I was at a hobby store. My boyfriend at the time liked doing model airplanes, and so we were picking up a kit for him to make a model airplane, and I was just browsing around. I saw this Teach Yourself How to Knit kit, and I’d always liked doing things with my hands. I went to art school for a time. I ended up with a double major in fine arts and psychology, so I really always liked doing things with my hands. I did a lot of pottery, painting, and drawing in high school and college. It’s hard to find a pottery studio to regularly go to, and it can be expensive. I was like, “I need something to do, and there’s this knitting kit.” I knew nobody who knitted. Nobody that I grew up with knitted. I didn’t have knitting grandmothers or my mom, or I didn’t have any friends that knitted. This was in 2005. I don’t know. It was a whim. I just thought, “I’ll give this a try.”

I tried teaching myself from the little pamphlet that came in the kit, and I started to have some trouble figuring things out. Thankfully, YouTube had just started, and there were some knitting videos on YouTube. I was watching those and figuring it out, and then I got stuck. At one point, I had cast on a certain number of stitches, and I had many more stitches than that on the needle. I didn’t know what I was doing wrong. I happened to go visit my parents at that time in Colorado. I asked my mom, “Do you know of a knitting store or anybody who knits who could help me with this? Because I don’t know what to do.” My mom said, “Oh, I think I have a friend who knits.” My mom took me to her house, and she helped me figure out what I was doing wrong. Then I was just off. I figured it out. A lot of the rest of it, I figured out by watching YouTube videos. It wasn’t for quite a while before I had any kind of community around it. I was the only person in my social circle who knitted. It meant a lot. I enjoyed it. The first two years, I think I didn’t make a single thing for myself. I just knitted gifts for friends. It felt really satisfying to be able to give somebody something that I made.

Then I got really into it in grad school because it was really a foil to the work I was doing as a therapist, where that work was so intangible, in your head. You didn’t really know what was always happening in the room. There’s so much subconscious material floating around and everything. It felt really good to ground myself in something tangible. Also, grad school took away my love of reading for pleasure, which had been my primary hobby, and I needed something else to do. I found a group of knitting psychologists, mostly, that met in a local pub called Sheep Station, which I thought was very fitting, in Brooklyn. I had community around it, and then it became so central to my friend group. I taught other friends to knit who didn’t knit. Now my friend group has lots of knitters in it, both because I’ve gravitated towards groups and made friends, and also because I’ve gotten people in my life to knit who did not before.

It took on new meaning during the pandemic, as I describe in the book, where it was fulfilling all of these needs that needed to be fulfilled through the materials of the home that I couldn’t really meet in the ways that I had before with things outside of the home. That is what led me to then think about what this work meant for women throughout history, when more of the needs did have to be met through the materials of the home for both men and women, really. The home was the center of economic production. It was, largely, the center of life. Communities were small, and the work of the home took up the majority of people’s time. That was the path.

Laura: Can you explain a bit more about how the book came together and how the idea emerged out of your pandemic ponderings?

Nicole: As a psychologist, I’m really interested in just how we make meaning. I’ve always gravitated towards these existential humanistic perspectives and theories, just this idea of life is inherently meaningless, it’s up to us to make meaning from what we have to work with. I think that I was finding during that pandemic, it was such a reorientation of life. It really made, I think, a lot of people look at, “What are we doing? Is the way I’ve been living the way I want to keep living?” Because it was this full stop to a lot of activities or a lot of aspects of life. I know lots of people reconsidered relationships they had. Who did they miss during the pandemic? Who did they not miss? Who did they stay in touch with? Who was a support during that difficult time, and who was not? I think it just made us all reflect on, “What are we doing with our lives? Is this the way I want to live?” I think some people were very glad to go back into life as they had known it before, after the pandemic. I think a lot of people changed a lot of things, whether it’s that they got to continue working from home and that shifted some of the balance of their lives.

A lot of what was happening for me is that I was realizing I had been on this trajectory that I thought I had to be on: this academic research, busy hospital, grant-funded research career. I think I felt like I was supposed to be struggling. I had two little kids. I thought it was just supposed to be so hard. If I wasn’t working at maximum capacity, I wasn’t doing enough. The pandemic made me slow down with that. I didn’t have childcare. I didn’t have anybody to support the household other than my husband and I, who were both balancing full-time jobs with childcare. I couldn’t do as much in my job as I had. I had to prioritize things differently. I didn’t do research. Research was on hold. I didn’t have time to write papers or write grant proposals, and everything the way that I had been.

Then I had all this time with my kids, which I hadn’t had before. I had weekends with my kids and a couple of hours in the evenings with my kids. I had now many, many hours a day, many more hours a day with my kids. They weren’t spent going to birthday parties and play dates; it was just being home with them. Knitting was something I could do during that time that I was there with them. It was really the only thing I could do for myself in the context of this, because I didn’t have alone time. If there was any time, it was writing notes from my sessions or preparing for teaching a class to my students. There wasn’t like, “Oh, I’m just going to go sit in my room alone for a couple of hours.”

I was realizing how much knitting was fulfilling me during that time and how much I was able to channel and fulfill in that, that wasn’t getting fulfilled through my research anymore, having that on hold. Research had been this place that I channeled a lot of creative and intellectual energy. I had a lot of community around that because I had research collaborators, and we would talk and write things together, plan projects and plan grants, and send drafts of things back and forth. That wasn’t happening as much, but I was sending pictures of my sweaters to my knitting friends, “Look, I’ve got this almost done. What do you think? Should I make the sleeves a little bit longer? Do you think they’re good here?” All of that felt like that collaborative aspect of research was getting fulfilled in the knitting. It made me think about times when women didn’t have the opportunities to be researchers or engineers or whatever, the many things that women are able to do now, that this was a place that offered room, offered these possibilities of fulfillment.

A lot of aspects of daily life don’t offer fulfillment for men or women. There’s a lot of things that are rote or repetitive in a way that doesn’t offer a lot of opportunity for creativity or intellectual engagement. Cleaning your bathroom probably is not the most intellectually engaging activity. Textile production can be very rote and repetitive, too, but there’s also creative problem-solving that has to happen. When you set up a warp for a loom, how many warp threads do you put on? What is the pattern you’re going to weave? You’ve got to work out that math. You’ve got to figure out if you have multiple different patterns, and will they all repeat over the same number of warp threads? How do you make that work? Then what colors do you use? What patterns do you combine? What do you want this thing to look like? What do you want it to express about you? There’s a lot more to it than a lot of other tasks of the home.

I got curious about what did this work mean to women at different times and places, and how did they use it as a material for finding meaning and fulfillment? I started reading, and I read some incredible books that were really interesting and eye-opening—I did find a lot centered on larger cultural practices or the economic significance of creating textiles, all of which are hugely important, but there was very little that I found that spoke to any given woman’s experience. What was it like for the woman? Of course, historically, we don’t have a lot of firsthand accounts of women writing about their experiences. We have some, which are treasures, but we don’t have a lot. Because it was such a pedestrian activity, it probably wasn’t even something that many women would have written all that much about. It was taken for granted that this is something people did. It wasn’t particularly unique. Men might not have commented much on it either or wondered much about it.

There wasn’t much written on it, and so I was feeling like, “Well, I want to know. How could I find this out?” I started interviewing people. I interviewed people who were textile creators themselves, knitwear designers, weavers, artists in the textile or multimedia kinds of fields. Then I talked to art historians and anthropologists and archaeologists, wanting to understand different time periods and different cultural practices around this, and what it meant for women, say, in Indonesia, who are doing it as part of, in some sense, a spiritual practice. It has this cultural and spiritual significance, and they’re weaving things to ward off evil spirits, or they’re weaving things to bring good omens on their families. I wanted to understand the meaning of it for these different women, so then that was the beginning of, “Well, maybe I should write something, myself, about this.” I was a researcher. I’m used to finding gaps in the literature and then saying, “Oh, here’s a gap. This is something that I could fill.” I had this experience of my own fulfillment in it, and I wanted to broaden that and understand the complexity of that for other people in different time periods.

Laura: You weave together all of these different fields really beautifully, like anthropology, art history, sociology, and psychology, and then oral history. How was it approaching the research and putting it all together?

Nivole: It was definitely a challenge. I do think I’ve always been very interdisciplinary in the way I think about things. I was drawn to psychology, in part, because it’s so interdisciplinary and brings together philosophy, gender studies, and sociology. I like that, and I like that the work of a psychologist is very varied too. You can teach, you can write, you can be a therapist, you can do research. I like being able to draw on a lot of things, and I’ve always, I think, liked synthesizing things from across disciplines. I was very torn throughout my teens and 20s, what to do with my life, because I had a lot of interests. This was a real treat for me to get to bring together all of these things in this book and explore this topic from all of these different avenues. That felt natural to me in a way and felt really satisfying.

Actually, then working with the data and putting it together was a different experience than I’ve had. I did always do qualitative and quantitative research, so I’ve liked mixed-methods approaches to things. Having had qualitative research experience, I felt like, “If I treat this as a dataset and then I’m looking for themes and I’m looking for ways that these things group together, then that’s a way to start to organize and put this information together.” I knew that I wanted the chapters to reflect different forms of meaning, like social connection, intellectual fulfillment, creative expression, and the economic aspects of textile work. I knew I wanted to use that, so I thought, “What are some key areas of meaning-making? What makes life meaningful?” That organized the chapters themselves. Then within the chapters, for each chapter, I had maybe 60 pages of a Word document with all the different things that I had found, snippets of interviews or stories that I had heard, and historical accounts. I had found some great historical accounts. I’m sure there are loads more out there. I drew on what I found in terms of journal entries or letters. Virginia Woolf wrote some letters about knitting and what it meant to her. I would put them together in the chapter that I felt like they belonged, and then I would organize from there and just say, “What are the themes that are emerging here? What are the aspects of social connection that seem important and that are getting spoken to in this data?” Then it’s grouped from there.

I could have put it together more linearly and tried to follow the development throughout history. That didn’t feel like it expressed quite what I was wanting to get at, which again is these areas of meaning-making. It’s not chronological. It moves around between different time periods and different places in the world. For somebody who’s looking for a history on textile work, this isn’t it. It’s much more fluid than that. I think that, hopefully, the ideas about what this work means to women, the ways they’ve created meaning from it, come through by the way things are organized.

Laura: You’ve referenced your previous research. What was your previous research in, and how do you think your background in clinical psychology helped you with this book?

Nicole: I worked at the Manhattan VA, so it was largely with veterans and largely looking at alternative treatments for veterans who did not respond to the typical CBT treatments that are used in the VA system, [like] how to develop more psychodynamic approaches that would maybe reach these patients who were not being helped by the more traditional treatments that have been used in the VA system for the last 20 years. I was doing development for PTSD treatment for non-responders to exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy. Then I was doing a depression treatment for veterans who had depression and interpersonal difficulties, helping create better support networks to also help support mental health. Prior to that, my dissertation was on narcissism, so I was doing personality disorder research.

My clinical work, again, I think I’m very interested in individual people. Again, why I was not satisfied by a lot of what had already been written about women’s roles in textile production was that they combined people. It was just like, “This is what it meant for women generally in England in the medieval period,” or “This is how it functioned economically in this period.” I really wanted to know individual experiences, and then knowing, as I do, how creative people struggle to live creatively, to find meaning and purpose in the world as it’s structured and everything. Thinking about women at these different times, and how did they navigate those challenges, that’s been a challenge for me. I do want to live a creative and artistic life and express my ideas.

There aren’t a lot of opportunities when you’re focused on survival in whatever context, whether it’s 500 years ago, and survival maybe means something different than it does now, when a lot of your time and effort is going to just focusing on how to earn an income or provide for your family. Where do we find the spaces to satisfy needs for creativity or intellectual engagement? I imagined we’re probably not that different than women many hundreds of years ago who also had desires for social connection, intellectual engagement, and creative expression, that this is, maybe, part of human experience more broadly. What role did textile work play in that process? I wish I could go back and speak to women in these different times and wonder about that. I did get some glimpses through some historical writings and journal entries. It was really great to see the meaning that this had for people throughout history.

Laura: It seemed like you were able to do some travel for this, to talk to people today in various parts of the world. Where did you go?

Nicole: I went to Peru, Iceland, France, Portugal, and Gee’s Bend, Alabama. I couldn’t travel everywhere, but I talked to people in Nigeria and the UK, Scotland. I talked to people all over the world to fill in some things that I couldn’t do in person.

Laura: Those research trips must have been quite amazing.

Nicole: They were. Peru, in particular, was a very special trip. They have a different way of engaging in textile arts than a lot of other people I talked to where, for people still living in Indigenous cultures there, there is really this long ancestral connection to this work, a spiritual connection. It’s still intertwined in how people express themselves, express their ideas, express their culture and their history. That was really such a rich experience to learn from them, the meaning that this work has, in such a very deep way, so much so that when I would ask a lot of these women, “What would you do if you couldn’t weave anymore?” I got no response. Either people would just not know how to answer that question, or they would say something like, “Well, I’d spin the wool,” or “I’d take care of the alpacas or something.” They couldn’t imagine something that didn’t involve this work.

It’s threatened there too. There’s movement away from Indigenous communities, for economic reasons and everything. I talk in the book about these efforts to maintain these traditions by organizations that are working to provide a living wage for weavers and more rural communities so that they can stay in those communities and maintain these traditional practices that are so critical to the culture and history of these places.

Laura: Researching and writing this book, did it change the way you felt about your own knitting, your own textile work?

Nicole: Yes. It felt like it connected me to a much larger community, which was really gratifying, especially coming out of the isolation of the pandemic, to feel like, “Oh, wow, it’s not just my 10 knitting friends or something that I’m connected to, but I’m connected to this whole world of people who are doing fascinating things and meaningful things, and bringing their own ideas to it, making it something of their own.” It was a very rich experience to feel connected to this, and to be then knitting in the context of this larger community and feel like a real part of some long history of it, as well as a really vibrant, active community now. I think maybe because I didn’t have a knitting grandma or something that made me feel connected to a lineage, writing this book helped me feel like, “Oh, there’s been all of these women before me that have been doing this work and maybe finding meaning in it, in a way, in some ways similar to my experience.” That feels really great.

I’ve talked to women who feel connected to an ancestral lineage because their mom, their grandma, their great-grandma, whatever… they have pieces that their grandma knit for their mom when they were babies. They feel like they’re carrying this on, but I didn’t have that. I found out my mom’s mom did actually quilt in the ‘40s, ‘30s and ‘40s. She stopped by the time my mom was born in 1950, but for my mom’s older siblings, she would sew some of their clothes, and she did make some quilts. I have a quilt that she did not finish, which my mom only thought to tell me about when I was writing the book. She was like, “Oh, I have this quilt that grandma left for me to finish, but I don’t sew and I wasn’t going to do anything with it. I’ve got it in the closet and I think she even gave me the fabric and everything and maybe you’d want to finish it.”

It’s this giant yo-yo quilt. It’s a king-size coverlet, and it was missing 20 yo-yos. I figured out how to make yo-yos and I had my daughter do some, who’s now 10, but I think was 8 at the time. I made my mom do one. I made one of my cousins and her daughter do one as well so that we all connected the work of our hands together with my grandmother’s, so it’s four generations connected in finishing this quilt. That meant a lot to me, but I didn’t know any of that growing up, and I didn’t know any of that going into the book. It did even connect something to my own ancestors too, through this that I didn’t know was there. I think that’s been a big thing.

I also tried a bunch of different textile arts during the process of writing the book because I wanted to know what these different things felt like. I really had mostly knitted, although I did do some sewing and made clothes for my daughter when she was a baby. I had never really done embroidery or weaving or spinning, and I had never really done quilting. I’d say I was a pretty beginner-level sewer, but I really did take to some of these different textile crafts too. It’s been fun to have more mediums open to me. It parallels the interdisciplinary nature, a bit, of my academic work that I really like having a lot of different things to pull from and ways to express ideas. It’s opened up my world a little bit more too, in the kinds of things that I create and the materials I use.

I’m so much more aware of what’s happening in the quilting world, different forms of quilting, and ways that I might enter that, that feel like they could fit me. Traditional machine quilting didn’t hold as much interest to me, but I found English paper-piecing very interesting to offer possibilities that align maybe more with my aesthetics and also the way I like to work. That’s a lot of hand-stitching, which I can do in a portable way, which fits into my life better than needing to be at a sewing machine for a number of hours, which is harder for me to do with young kids. If I can stitch some pieces together in front of the TV with them at night, or if I can take some stuff on the subway, then I can make progress on these things in a way that fits into my life. Maybe at some point, my life will be such that I can sit at a sewing machine for several hours when my kids are teenagers or something, but it’s not there yet.

Laura: Talking about kids, how did you balance the research, the travel, the writing, young kids, and private practice all together?

Nicole: Again, I think I like doing a lot of different things. That’s coming even more clear to me as we talk about this. I like having variety. I knew going into my career as a psychologist that I would never want to be a full-time clinician. I always wanted to do a mix of things, and so my job at the VA was great because I could balance research, teaching, supervising, clinical work, and some annoying administrative stuff that I didn’t enjoy so much, but it was nice having the variety.

That was such a challenging and time-consuming job, especially with such young kids. I left the VA when my kids were, I guess, four and six or three and six. They were starting to get a little bit older. They went back to school after the pandemic, and so I had a little more time. Private practice, I see 8 to 10 patients a week. Maybe at most, I had been seeing 12 to 14, but once I got the book deal, I think I was seeing more like 8 to 10. I had a half-time private practice and then a half-time writing job. It actually felt quite a bit calmer than my VA job. This felt like a simplification in a sense, which does sound strange given that it was still so much work.

The travel, some of it was going on my own and leaving my kids behind, and my husband being very generous to care for them for two weeks while I was in Peru, but some of them were family trips. We all went to France together, and I would break off for periods of days to go do interviews, but it was tied into a family vacation. Then some were shorter trips. I went to Gee’s Bend for three days and interviewed quilters there. It was trying to fit them in together as much as possible and have them be experiences that didn’t always take me away from my family, but that my family could share in.

Laura: I have a baby, so I’m always interested in how other people do it, how other female writers manage. Returning to the book, which women’s stories—and they could be historical or from interviews—either most moved you or most surprised you, made the largest impact?

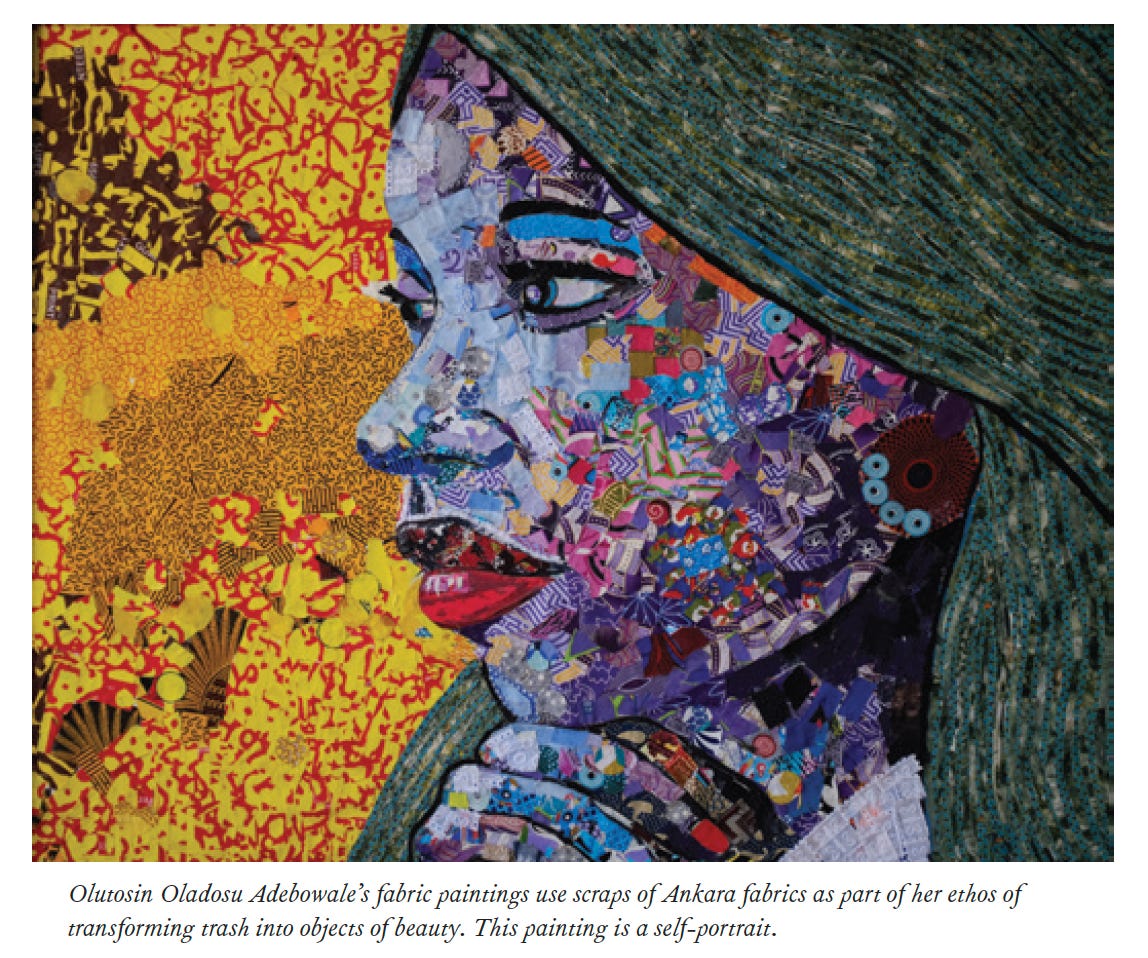

Nicole: I felt like so many of them touched me so deeply, and that the interviews were such meaningful experiences for me too, and collaborative experiences where I would come in with questions, but where we would end up going with it and everything felt like this real exploration. I would say, and I talk about this at the end of the book, there was this woman, Olutosin [Oladosu Adebowale], that I spoke to in Nigeria. The call with her was really moving. She had come to textile work following an incident where she was badly abused by her husband. She was trying to find herself again and find her value. She started making these textile pieces. I think at first it was purses, little pouches, and things out of scraps of fabric. She didn’t have money to buy fabric, so she would ask tailors for the clippings from their projects, things that were too small for them to use. She started making these beautiful pieces out of those, and in that process, finding her own value. “If I can make something beautiful out of something that’s been discarded by somebody else, then maybe I have value, I have worth, and I can make something beautiful out of a life that has not been valued by others.” The parallels in that I felt were just so deep and thoughtful and really powerful.

Then she’s transformed her experience into this larger community project where she teaches women to sew and has created a whole village called Sisters City where women who have experienced gender-based violence, domestic violence, or have been outcast from society. There’s still a practice of treating women as witches, especially older women who don’t have a reproductive value to society anymore and everything, to dismiss them. Bringing together all of these women and making it a therapeutic experience and a safe experience to live together, to learn how to create together. They weave and sew, and then are able to go into business on their own and sell their work, or go into a business as a tailor or something, making dresses. It’s really, again, a way of restoring dignity to women who have been treated badly or who have been outcast and show them their value through this experience of creating with textiles. That was such a powerful story to me and really summed up so much of the psychological aspect of this work, that creating textiles isn’t just about making a cover for a bed or something. It can be so, so much more.

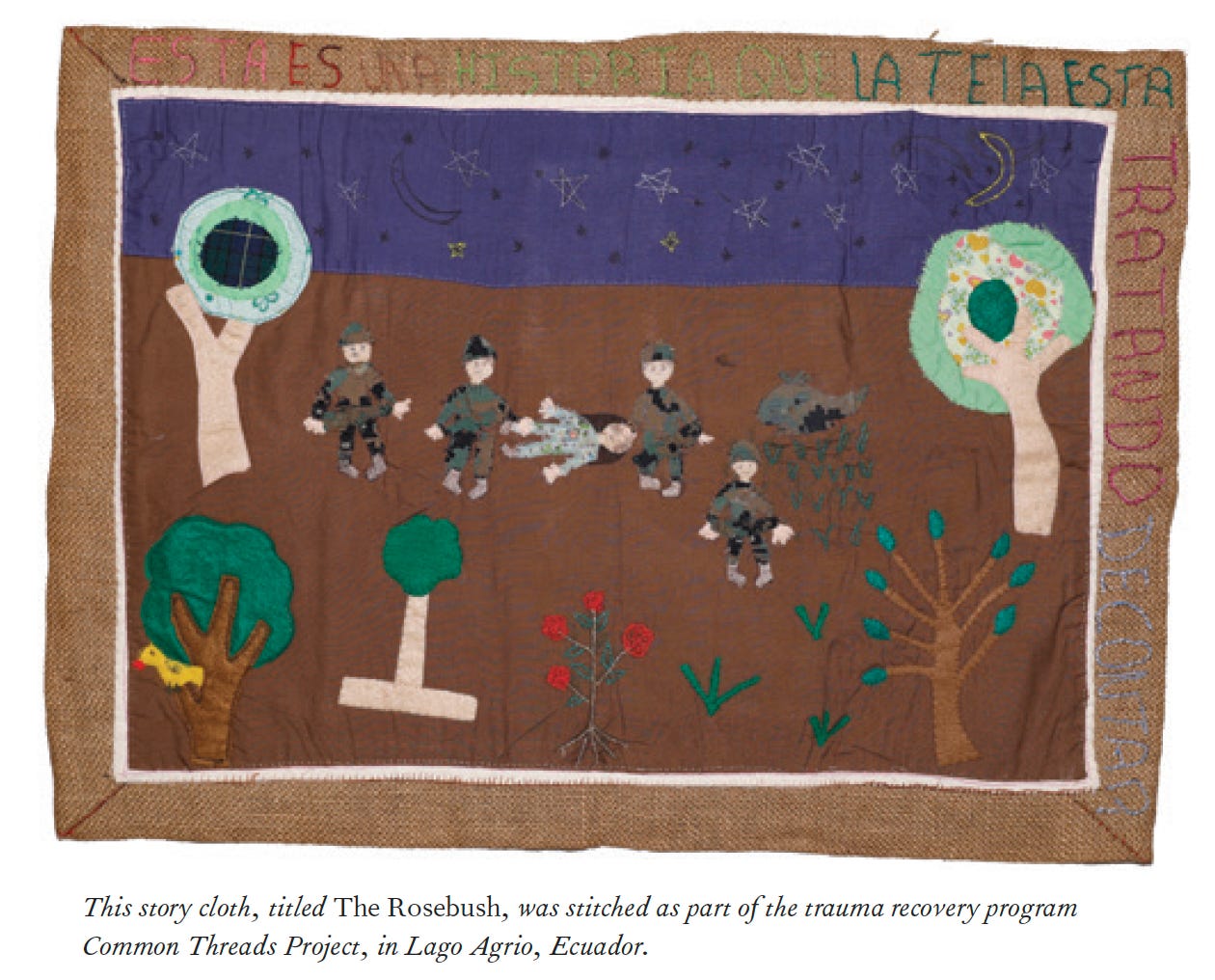

Laura: The stories about the different groups that have women working through trauma, I found those really moving, especially the woman’s textile piece with her daughter embroidered, following a rape. It’s really emotional looking at and seeing the pain in that. Reading your explanation of these groups that work with women to help them, it’s really heartbreaking work, but obviously really worthy.

Nicole: That’s another place my clinical work has now intersected with my textile interest is that I’ve started running a group for the Common Threads Project that you’re talking about, that “The Rose Bush” was part of. My work as a VA therapist was largely trauma processing work, and so I’m able to now do this trauma processing work through textiles, through the creation of story plots, which is so wonderful for me. I never thought I would really get to merge these things so much.

I had co-led at times while somebody was on maternity leave and everything, a group at the VA, a knitting group, that was women who had PTSD. It wasn’t a trauma processing group, but it was just a knitting support group. Sometimes we’d touch on traumatic material or other difficulties in their lives. To be able to really do the therapeutic work through the textile practice just really perfectly combines these interests for me and feels like such a meaningful way to do trauma processing work.

Laura: Have you gotten feedback about your book from people in the textile and knitting worlds yet?

Nicole: It’s been wonderful to hear from people. I’ve gotten messages from people all over the world. I got a message from a woman in Slovakia and Romania, and a woman in Brazil, just all over the world about how this touches them. They want to share a story with me about how they’ve come to this work or the meaning of it in their families. That’s been really great.

The best part of writing this book was talking to women and hearing their stories. I love that in the aftermath of publishing the book, I get to hear even more of these, because I really lamented once I was done with the interviews. I would have done interviews forever. That was the best part of it, and so I love that.

When I do events too, I open for a lot of discussion. I want to hear people’s stories. I just hear such wonderful, rich reflections on people’s own textile practices and what it means to them, the way they use this work, or the way they came to it. It’s just wonderful. I love all of these stories that I get to hear. I feel that way as a therapist, too. It’s such a privilege to be able to hear so much about somebody’s life and for them to trust me with these stories and these experiences, both difficult and wonderful. I feel the same way about this experience of writing the book, getting to talk to people, and hear these stories. It’s a privilege.

Laura: Wonderful. Congratulations.