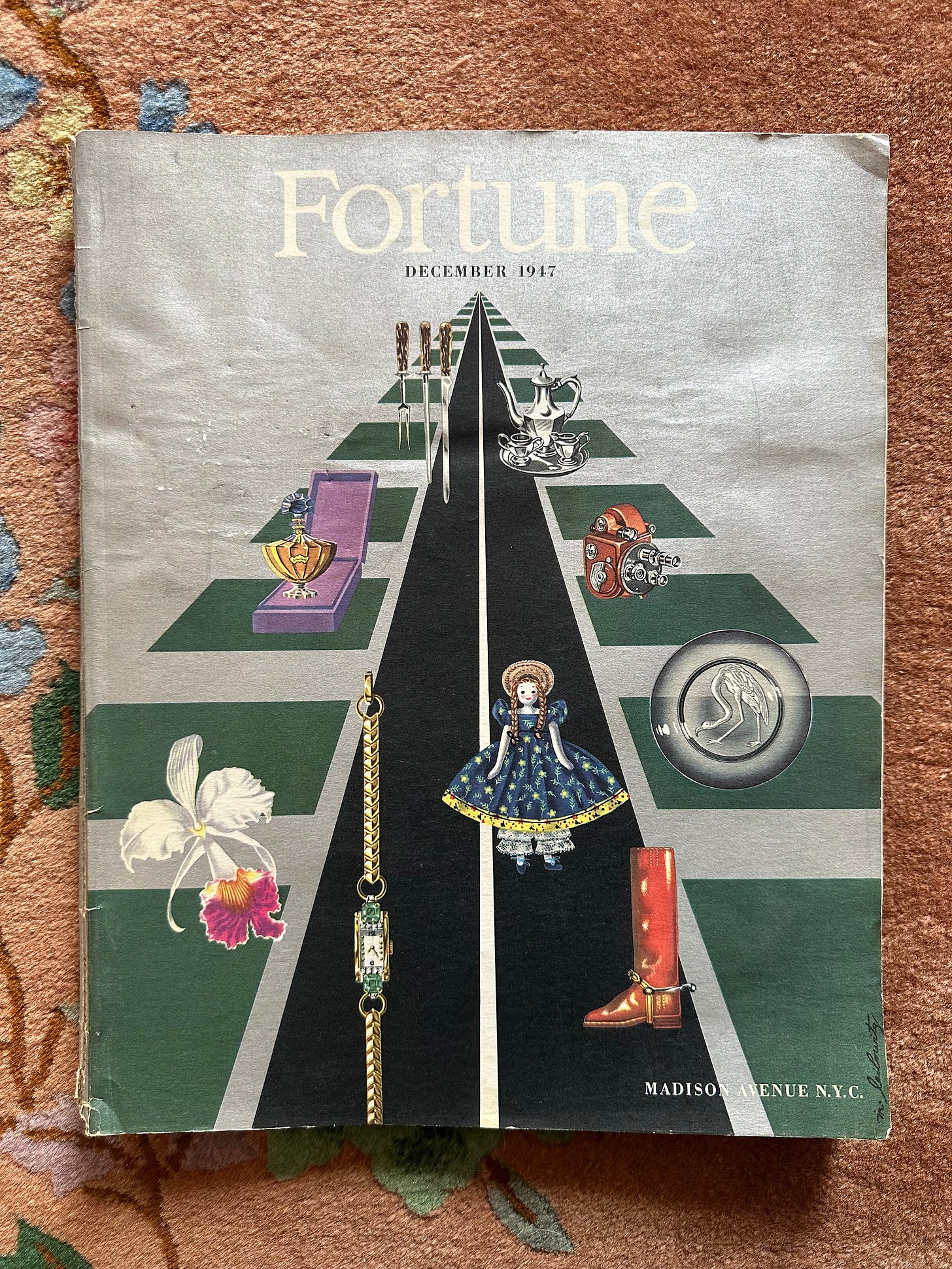

In its December 1947 issue, Fortune magazine put Madison Avenue as the Main Street of New York City. As defined by the preservation and development non-profit Main Street America, “Main Street” is “a place that has a thriving local economy, is distinctive and rich in character, and features welcoming spaces and diverse businesses for residents and visitors alike.” For academic Miles Orvell, in his book The Death and Life of Main Street: Small Towns in American Memory, Space, and Community, “Every town or settlement in the United States has a central artery running through it, and in most cases that road or avenue is called Main Street: it is the essence of the small town and synonymous with it.” Therefore, Madison Avenue could be seen as the essence of New York City—the city at its most fundamental.

To create this comparison, Fortune places Madison Avenue in opposition to the department stores of Fifth Avenue—all-encompassing, impersonal, momentous against selective, intimate, approachable—“a good street to stroll in, with all the city's mundanity and none of its monstrosity, a street in which a New Yorker can feel uninterrupted by the world at large, can feel himself at home.” The very idea of the American Main Street that Fortune compares Madison Avenue to is, to us, long dead—killed not by department stores (which have been similarly dying) but by retail forms not yet invented in 1947: the shopping mall (Victor Gruen’s Southdale Center is generally considered the first, in 1956) and discount department stores (Walmart, Kmart, Target, and ShopKo all started in 1962, though there were some earlier chains like Caldor, founded in 1951). By the 1970s, there were already calls to save dying Main Streets across the nation, leading to the founding of Main Street America in 1980 to aid in the revitalization of commercial districts via economic development and historic preservation.

NYC’s streets might not have been as affected by the exodus to the mall and Walmart as the quintessential small-town Main Street, but they have been ravaged by another foe: chains. Identikit coffee shops, banks, drugstores, and fast fashion stores, block after block, have pushed out many of the types of unique stores discussed in this article; this can be seen not just in NYC, but on high streets across the UK and other European countries. A celebration of Main Street—or in this case, Madison Avenue—is a celebration of small retailers with expert knowledge, personal service, and a smart selection; something that I think every shopping lover misses.

Reading this portfolio makes me want to shrug on my warmest coat, go out into the frigid city, and hunt down all the little hidden retail jewels. Of course, this applies to not just New York—part of the wonder of traveling or moving somewhere new is the process of discovering local stores tucked quietly behind the Zara’s and the Starbucks, places that bring joy to one’s existence. As the wildfires swept through Los Angeles this past week, I thought of all the unique stores I’ve discovered in neighborhoods across the city.

wrote of them in her newsletter, how the “PCH itself was like a string of mismatched trinkets, a bonsai store next to a shitty souvenir shop next to a Michelin-starred restaurant next to a cattle- and horse-feed store.” Similar to Susan, I have “found the rattle and jangle of these disparate elements intriguing, a sort of visual jazz composition, dissonant and raw.” It’s been heartbreaking to see how many small businesses in Altadena, Pacific Palisades, Topanga, and Malibu have been lost, but also heartening to see how the community has rallied around them.I, like many others, have fallen into a habit of being too dependent on Amazon and other online retailers for quickly and conveniently procuring the most basic of household items—yet every errand saved is a lost opportunity to interact with the world, our community, and support local. If I have a resolution for 2025, it is to curtail those Amazon purchases (so quick, so thoughtless) in favor of more pedestrian shopping excursions (baby in tow).

Fortune (no author is credited) takes the reader on a journey down the Avenue, documenting the street’s inception and the forces that continued to mold it. It’s a snapshot in time, right after World War II, of a world-renowned place and the many people and businesses that helped make it so special. This weekend I will send out a deep dive through the second part of the portfolio, in which Fortune highlighted specific businesses. While most of this world is long closed, there are still glimmers of it on Madison Avenue—historic shops, preserved buildings—that inspire a desire to look more closely at the legacies of shops, restaurants, and other businesses everywhere.

“A portfolio celebrating one of the world's choicest and most unpublicized shopping centers—Main Street to many New Yorkers.”

Fortune, December 1947. Photos by Fons Fanelli and Myron Ehrenberg.

It is highly unlikely that any single person has ever visited New York City for the express purpose of seeing Madison Avenue. Yet to the thoroughgoing New Yorker—and he is a curious sort of man who never regards Radio City as the living heart of the metropolis—Madison Avenue is an especially appealing thoroughfare. He will be strongly inclined to agree with the advertising man Walker Everett, who himself works among the more spacious pomps of Fifth Avenue, but who once fondly described Madison as the true New Yorker's Main Street.

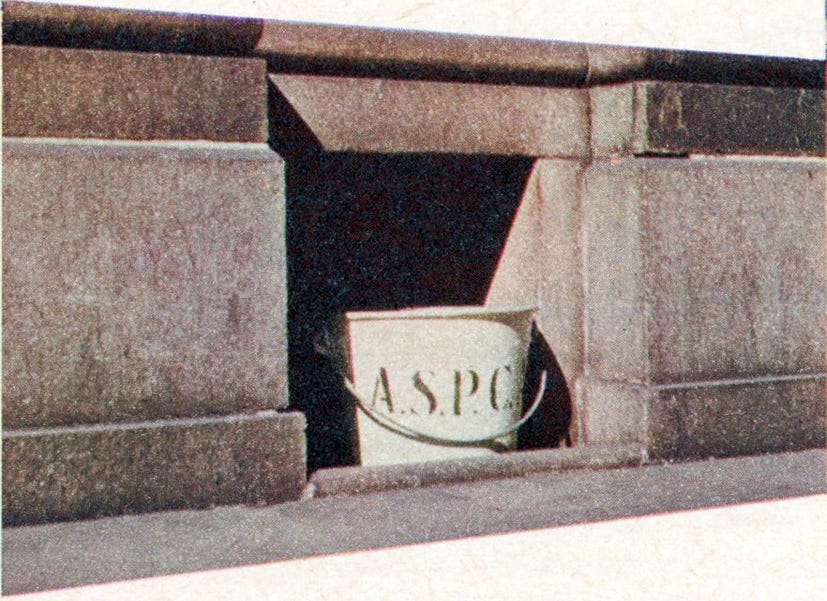

To outlanders, this may call for explanation. The idea does not come solely from the fact that Madison, situated between Fifth and Park avenues, contains some of the most notable New York institutions, such as Brooks Brothers, Tripler, and the Ritz, Abercrombie & Fitch and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. An even longer roster of significant piles may be found on Fifth Avenue itself. Nor does the idea spring from the indubitable fact that Madison is one of the most fascinating shopping streets in the world. Fifth Avenue, again, is an even more bounteous bazaar. But when one adds that Madison's typical shops are noted for their intimacy of scale, and the quality of their offerings, one gets closer to the Avenue's particular claim on New Yorkers.

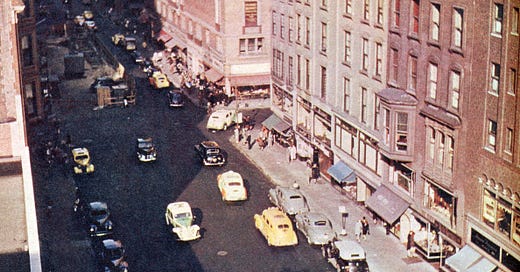

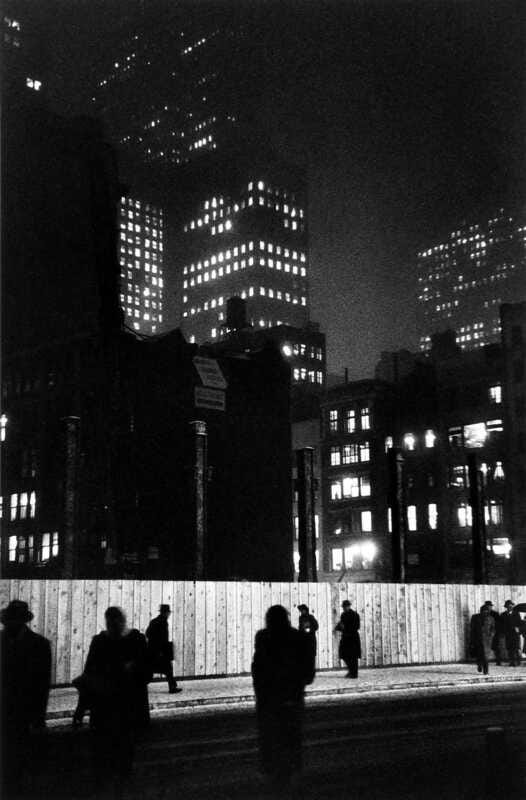

Throughout its length, Madison offers abundant material for the voyaging eye, from the swarms of girl secretaries spilling out of the great insurance towers at the Avenue's southern end, around Twenty-third Street, to the two miles of decaying brownstone and store-front churches in the soiled, vivid districts of Harlem, which finish the Avenue off to the north. But what the secure New Yorker means when he says Madison Avenue is the central portion of the thoroughfare, those other two miles of small and handsome retail shops proliferating between Forty-second and Eighty-sixth streets. They pass through the midtown business district and on upward through the social reaches of the Upper East Side. And they display the most select articles of commerce with arresting luster and uncommon taste.

On Madison Avenue, for instance, you will find flamboyant Renaissance hats designed by the Talberts, mother and son—he was a G.I. in Italy, and the Renaissance captured him there. The Midtown Gallery offers exquisitely classical line drawings by Paul Cadmus, and Egon Bernath makes suede sport clothes styled with such brisk, athletic conservatism that they never go out of style. Two other establishments, Leather & Tweed and Sport & Travel, closely follow his lead. Nearby, America House is a cool, glossy showroom for the display of strictly handmade products of American craftsmen, from Maine's Rowantrees Kiln to Oregon's Ceramic Studio. Along the Avenue is Emil Vardi, a stooped, authoritative man who wears a monocle, a signet ring, a pearl stickpin, and a diamond-and-emerald fob from which depend six seals bearing the coats of arms of six noblemen friends. Mr. Vardi will offer Georgian silver with such hauteur that, when Tallulah Bankhead was once obliged to ask the use of a particularly large vessel, he replied that he didn't give a damn what she did with it, she could bathe in it if she wished. Klauberg the cutler handles a shining trove of edgy goods, including the superb carving knives of Case. S. Semler is a second-floor shop devoted largely to buttons, and at the Persian Shop are sumptuous Near Eastern fabrics, jewelry, and gewgaws that are apt to be expensive even when the proprietor lapses into French and seductively offers "le prix le plus spécial de la maison."

Madison Avenue provides nothing less than magnificent foodstuffs at Shaffer's Market, and the raw fish of Wynne & Treanor, exhibited with the skill of a Ziegfeld, look good enough to eat. In the little Wilke Pipe Shop sits Joe Mutschler, hand-tooling pipes for his forty-fourth year. The interior decorator Rose Cumming charms her customers by lording it over their tastes. Clyde's has a dizzy array of brilliantly colored men's haberdashery, such as a green-corduroy bush jacket like an Australian soldier's. The Allerton Fruit Shop is just exactly ten feet square and stuffed with the world's prime delicacies—Turkish baklava, Egyptian style, Merken's Swiss bittersweet chocolate, Strasbourg foie gras with truffles, Spanish saffron, brandied Kelsey plums from Bordeaux, canned snails from Switzerland, West India lime juice, Ming and Tong teas, Dutch cocktail onions, boneless Portuguese sardines. The apothecary H. A. Cassebeer displays his superb pharmacopoeia in an elegant shop lined with light-blue Bavarian jars and profound-blue bottles. Branch banks abound; at the Bank of the Manhattan Co. the red-brick Georgian building has an overall resemblance to the famous Morris house of Philadelphia, with details from Boston's Old State House and the University of Virginia; women depositors are further stimulated by women bank executives in a room with white-organdy curtains, a burning fireplace, and much Currier & Ives. The trousseau shop of Emma Maloof sells sheets of pure silk with monograms, satin appliqué, embroidery, and real lace. M.J. Knoud deals in everything for the able horseman or poloist, including false tails for deprived horses. Ginsburg & Levy has perhaps the finest collection of colonial antiques in Now York. Uptown there are succulent shops devoted to housewares—a prominent one is W. G. Lemmon. J. & J. Slater is the kind of shoe store that once inspired Cissie Patterson to buy sixty-four pairs of its basic oxford and send them to friends all over the world. Madison, in short, is quite an Avenue.

The keynote is elegance on the intimate side. The secret of Madison Avenue's appeal for the New Yorker undoubtedly lies in the fact that, as a resident of the greatest city in the world at the peak of its influence, the summit of its size, the most oppressively crowded hour of its clogging life, he yearns by way of compensation for something small and discriminating. As a cosmopolitan, he wants quality. But he wants to find it in calm, uncrowded, embraceable circumstances. His city, wonderful and nostalgic as it may seem to him, is also monstrous. His other famous streets are depersonalized show places. Wall Street is a chilly crevasse, Broadway an increasingly gaudy midway, Fifth Avenue a jammed world boulevard, and Park Avenue a monotonous demonstration of the more solvent forms of undifferentiated domesticity. Madison Avenue, whose very name makes gracious intimations between the abrupt syllables "Fifth" and "Park," is a discreetly glowing street that has not become an international metaphor for anything, whose virtues and vices alike are all on the quiet side—a good street to stroll in, with all the city's mundanity and none of its monstrosity, a street in which a New Yorker can feel uninterrupted by the world at large, can feel himself at home. It is a prime characteristic that the customer is frequently known by name.

Madison Avenue was conceived in 1833, as a natural part of Manhattan's speculative northward expansion. Actual dirt began to be turned three years later. The name was derived from the Avenue's starting point, a suburban parade ground known as Madison Square after a tavern on its rim, Madison Cottage. This popular stop for businessmen posting from their downtown offices to country estates on Murray Hill had, to be sure, taken its name from President Madison. Only a quarter of a century later Madison Square had become the focus of the city's public and fashionable life, and Madison Avenue was one of the best residential addresses in town. The effulgence of Madison Square can in fact be dated precisely from 1860, when the visiting Prince of Wales elected to stay at the square's newly built Fifth Avenue Hotel. This had hitherto been regarded as "Eno's Folly" because its builder, Amos R. Eno, was thought to have planted the pile much too far north for sanity. Besides, he had indulged in the epicene foolishness of installing a passenger elevator. But the royal favor of the glamorous Prince Bertie made Eno the prince of American bonifaces, and his hotel presently became the headquarters of the North's high policy makers during the Civil War, and the center of an unprecedented and unsucceeded concentration of the city's most desirable restaurants, theatres, homes, and clubs.

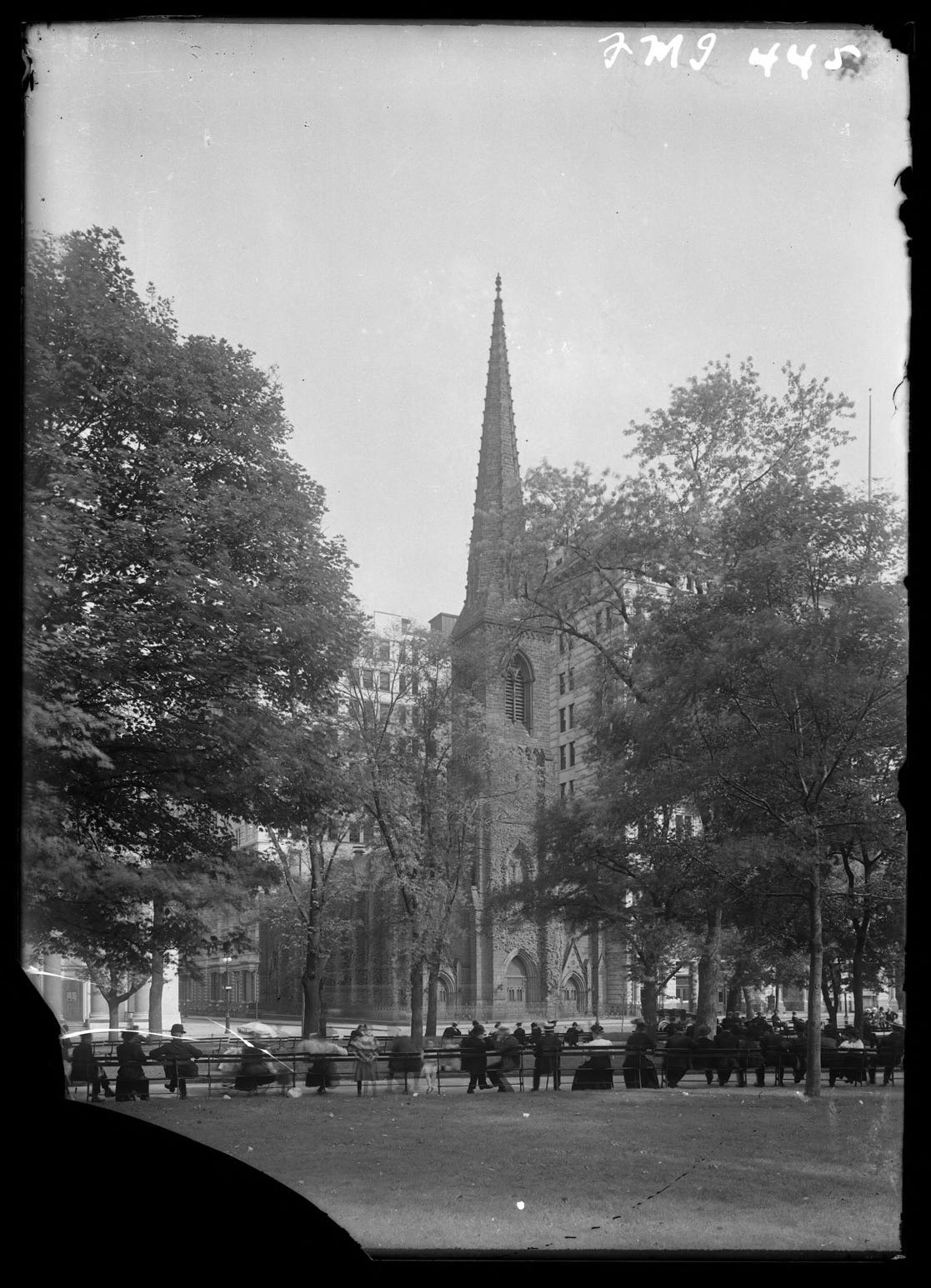

Madison Avenue's own monuments during the half-century heyday of the square have now all but disappeared. The soaring Venetian campanile of the Metropolitan Life replaces the brown spire of the church where Dr. Charles Parkhurst issued some of the city's sternest calls to moral order. And the Metropolitan's blocky New Annex replaces the successor church, with its cool dome and columns of green granite, mourned by many architects as Stanford White's masterpiece. The heavy Gothicized tower of the New York Life supplants White's famous Madison Square Garden, upon whose roof he was shot dead by Harry K. Thaw. But one venerable souvenir of the Delmonico days still adorns the square the patrician red-brick mansion that now holds the Manhattan Club, where once lived the financier Lawrence Jerome [editor’s note: Leonard Jerome], and his daughter Jennie, who became the mother of Winston Churchill.

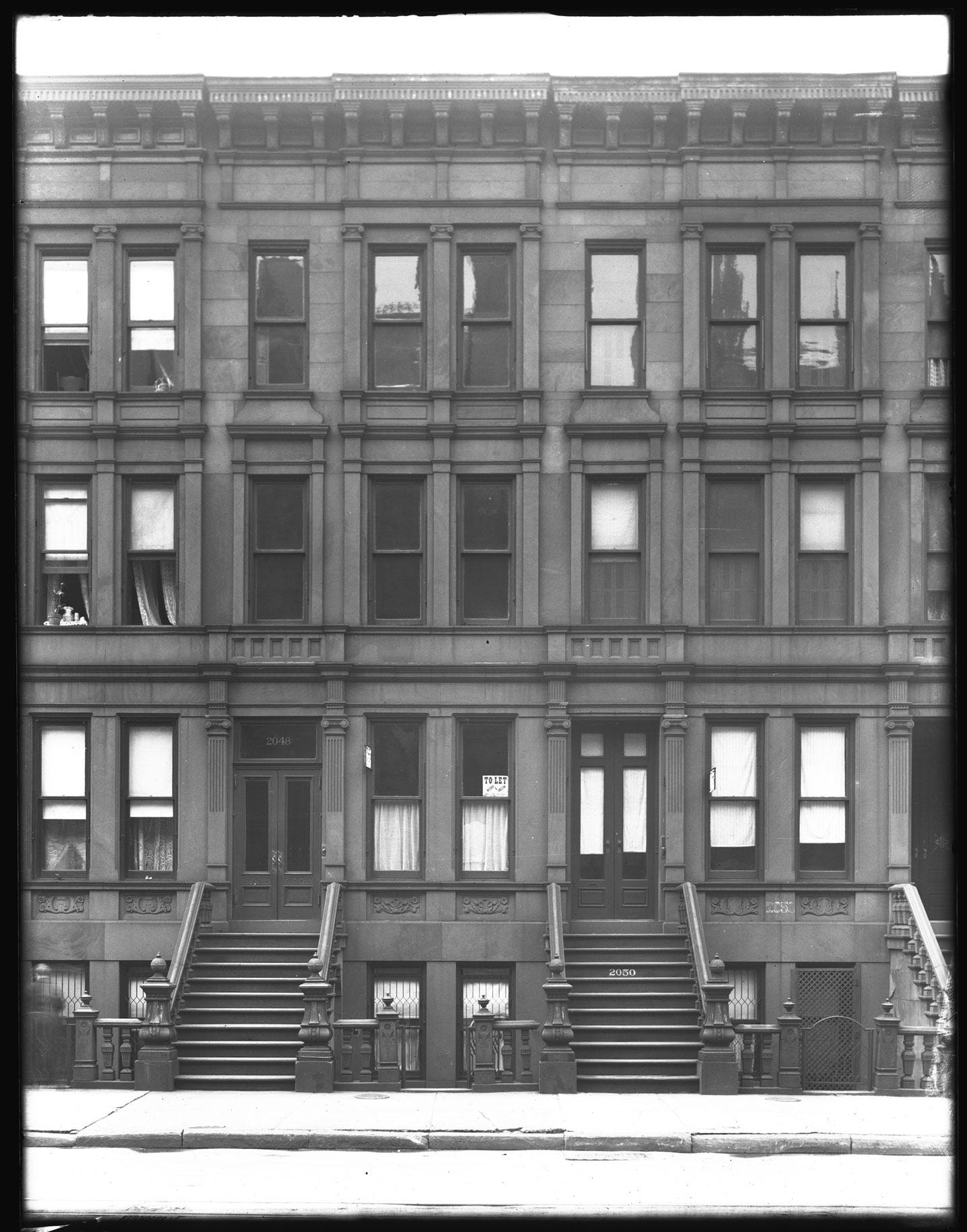

Aside from the Manhattan Club and the vast Florentine palazzo that belonged to Whitelaw Reid (and is now partly occupied by the publishing offices of Random House), little remains of what has been called the "Park Avenue of the nineteenth century." Its ranked brownstone houses contained the most substantial names in New York—Morgans, Villards, Reids, Pynes, Tiffanys, etc. Three Presidents of the U.S. lived for a time on Madison: Grover Cleveland and the Roosevelts. And for forty years (1857-97) the Avenue had its cultural crown in Columbia College, standing at Forty-ninth Street precisely where the New Weston Hotel now provides pleasant hostelry and one of the most generous public bars in the city.

The commercial development of the narrow isle of Manhattan was inevitably northward, and trade gradually replaced the First Families. Madison Avenue real estate between Twenty-third and Fortieth streets was assessed at $112,300 in 1840. The figure today is $87,075,000. Between Fortieth Street and Fifty-ninth, values have risen from $936,000 in 1864 to $127,952,000. From Madison Square to Thirty-fourth Street the Avenue's business is largely wholesale—a good example is the great negligee house of Tutundgy. The most conspicuous exceptions are the back door to Altman's and the big Shackman toy-and-favor store—both wholesale and retail. This stretch also contains the Madison Avenue Baptist Church, with the exotic distinction of sharing a building with the Roger Williams Hotel.

Between Thirty-fourth Street and Forty-second, a sweep containing the Morgan Library and mansion, the latter now taken over by the United Lutheran Church in America, the skyscrapers multiply and with them the business interests—one building directory, for instance, includes in its long list the Johns-Manville Sales Corp., the St. Louis Globe Democrat, and Woodlawn Cemetery. In this Murray Hill section, Madison Avenue's domestic pride made its last real stand against trade. The stubborn legal battle was joined for six years, from 1917 to 1923. It began when the William Waldorf Astor estate asked permission to erect a business building diagonally across the Avenue from the Morgan house—in a zone restricted by the city's Board of Estimate to residential structures. The Astors and Morgans tenaciously carried the case up through the courts to the state's highest bench, the Court of Appeals, where the Astors got the decision.

From that day forth, the Madison Avenue question has not been trade, but what sort of trade. Chiefly concerned is the Fifth Avenue Association, an influential body of merchants whose interests reach out to include Madison and Park avenues and Fifty-seventh Street. Steady fomenters of zoning laws, they have had much to do with the increasing spread of small, swank, retail shops along Madison between Forty-second and Eighty-sixth streets (their interest ends above Ninety-sixth, where Harlem begins). In 1926 the association began a campaign to raise the Avenue's tone by eliminating the "cumbersome and noisy trolleys." This required nine years' effort, but in 1935 the loud offenders finally gave way to subdued if uncomfortable buses.

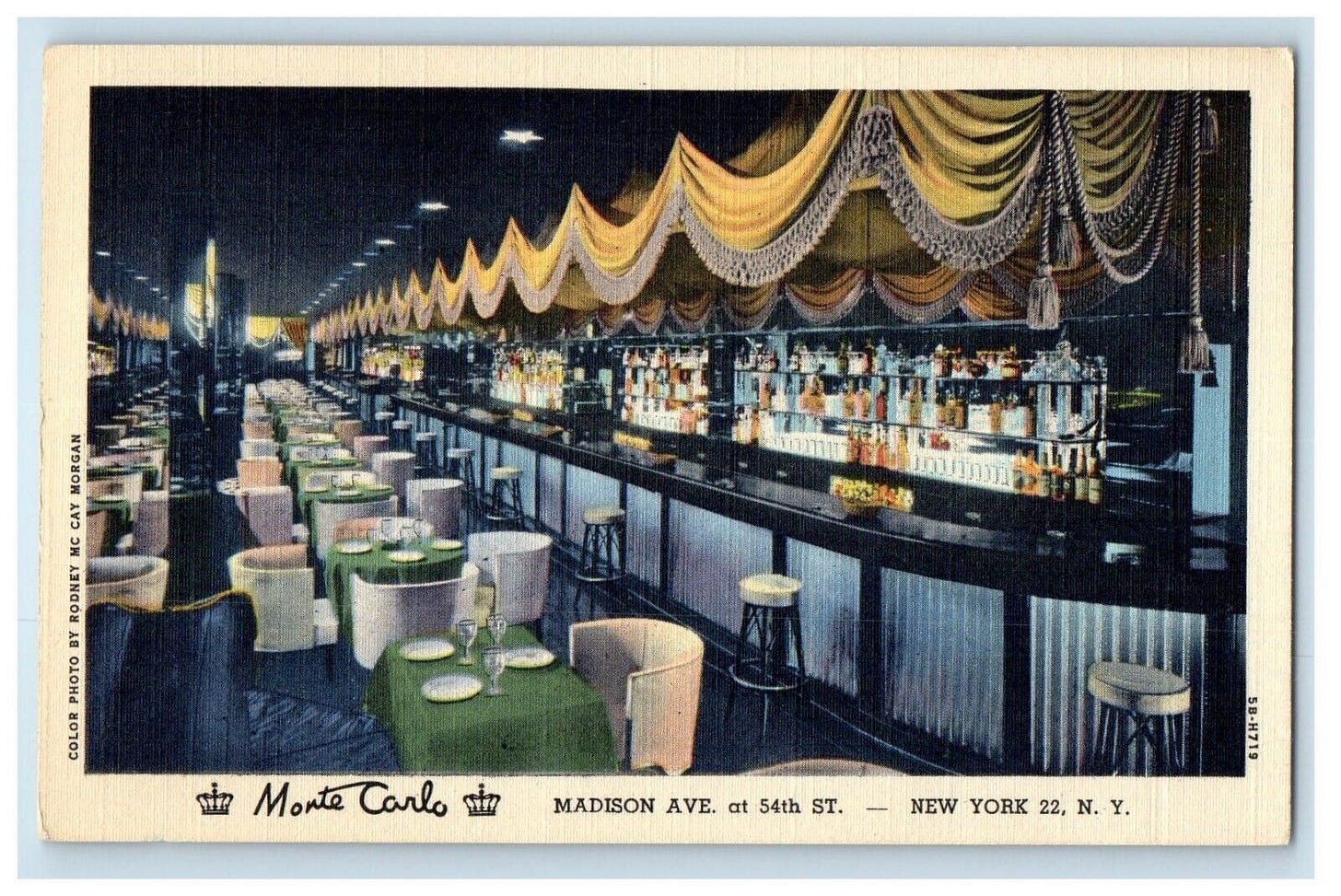

Meanwhile the Avenue, long classified as part business and part residential, was relisted as a retail district (1929) and then as a restricted retail district (1937). This prevents the establishment of new billiard saloons, cabarets or skating rinks other than those in hotels (the Monte Carlo nightclub gets by as "a restaurant featuring a distinguished French cuisine"), freak shows and wax museums, theatres, undertaking parlors, open-front stores, public dance halls, shooting galleries, skee ball, or similar pitches, warehouse and storage plants. Also forbidden are live models, moving window displays except where they are utterly logical (as with calculating machines), and illuminated signs projecting from the building line (Columbia Broadcasting System ducked this one on the ground that it is tantamount to a public utility).

Everything considered, the Fifth Avenue Association would seem to have assured the preservation of Madison Avenue's present character for an unlimited time to come. As the Avenue passes through the highly correct Upper East Side there is about it, summer or winter, a very proper quiet, duly pointed up by Frank Campbell's spacious brown-and-white Funeral Church (he got there before the restrictions). It is an Avenue of polite scale and nature, down which a finely tailored mother can stroll with her finely tailored daughter without once having to buffet hordes of outlanders or even of New Yorkers from more raucous parts of the city. And even farther downtown anyone oppressed by crowds, mass production, and large-scale merchandising is likely to appreciate Madison Avenue. It is New York's special and characteristically gilt-edged reminder that the unclamorous amenities of Main Street still exist.